Covid is coming: how to ride out the expected winter surge

It's almost three years since the first case of Covid-19 and another surge is expected this autumn. We look into the ongoing risks and necessary precautions for cyclists

Most of us are by now familiar with the experience of having our training or racing disrupted by a bout of Covid-19. The UK has endured three major Covid waves in 2022 alone, and more are forecast. Prof Karl Friston, a virus modeller at University College London (UCL), predicts that in late November there will be a spike bigger than any we’ve seen to date, with up to 8 per cent of the UK population infected, then a further wave next March. What do we need to know, as cyclists, to minimise the impact on our riding this autumn and winter?

The World Health Organisation also foresees a challenging autumn and winter ahead for Europe. A high number of cases increases the chances of new variants, which are likely to be more transmissible; whether they would cause more or less severe disease than the currently dominant Omicron variant remains unclear.

In the UK, only those aged 50-plus and the clinically vulnerable are being offered a vaccine booster, which is hoped will keep infections and hospitalisations lower in at-risk groups. Younger age groups, who were last vaccinated in late 2021 or early 2022, will find that their protection against infection has waned, though they should still be well protected against serious disease.

Whether or not you receive another booster, it is possible to take preventative steps to reduce your risk of catching Covid-19. On group rides, keep the spitting and snot rockets to a minimum, and be sure to wash or disinfect your hands when you can, while cafe stops for coffee and cake are best taken outside. If you’re feeling under the weather, skip this week’s group ride and take a lateral flow test, even if it’s just to rule out the worst-case scenario.

In the UK, ONS figures show that 95-96 per cent of the four home nations’ adult populations already have antibodies from prior infection or vaccination, while one in 36 people have reported symptoms of long Covid – where symptoms of the illness, such as fatigue, shortness of breath and brain fog, continue 12 weeks or longer after the original infection. While a study published in June showed that the latter is more prevalent in those with poor health, it can and has affected even super-fit athletes.

Long road back

“Even in the snow, I’d go out on my mountain bike to get my winter miles in,” says Charlotte Broughton. The 24-year old is recounting her early winter of 2020 as she prepared for her first season on a fully fledged UCI Continental team, AWOL O’Shea. Juggling 15 hours a week of training with a full-time job, Broughton was excited by what 2021 held. But just after Christmas 2020, she started to feel unwell. “I’ve quite a delicate digestive system, so I thought I’d eaten something that was off because I just kept throwing up,” she explains. But what followed were two weeks of aches and pains so bad she’d wake in the night crying.

“I had no energy,” she recalls. “I lived in this little cottage at the time, and getting up the really steep stairs was quite overwhelming. I knew that as a fit 20-something my body shouldn’t be feeling the way it did.” The aches subsided but breathlessness persisted, even during light activity. “I couldn’t fathom how my body could go from being so capable to a situation where small children could walk faster than me.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

After four weeks, Broughton returned to the saddle and slowly started to rebuild her form, but still could not manage intervals. “On long rides at endurance pace, I was fine,” she recalls, “but whenever there was any intensity demanded my body couldn’t react.”

Broughton also suffered from heart palpitations and underwent precautionary echocardiograms. “I remember being at the Tour Series in August 2021. I wasn’t nervous because I knew I wasn’t in a state to be competing for a solid position,” she says. “But then I looked at my heart rate and it was at 180 just standing on the start line. My resting heart rate is usually around 45.”

The ambitious rider is now back to winning ways, most notably at the Santini Women’s Otley Grand Prix back in June, but it has been a long road – including a complete three-month break at the end of 2021 on the advice of her coach – and the implications might be even longer lasting. “I have a feeling getting long Covid might have ruined my hopes of going pro,” she admits. “No one wants a mid 20s sprinter from England – unless you have the results, you’re nothing to them.”

Positive signs

While Broughton’s situation shows just some of the devastation Covid-19 has wreaked over the last three years, there are some silver linings. Vaccination offers a good level of protection against serious disease, meaning that if you do get it, it’s unlikely to make you seriously unwell. There is also now better informed advice on recovery and how to safely return to cardiovascular exercise like cycling.

“The biggest concern in athletes exercising when they’re unwell with any viral infection, but particularly with Covid-19, has been the risk of cardiac problems, a condition called myocarditis or pericarditis,” says professor James Hull, a consultant respiratory physician at the Institute of Sport Exercise and Health, UCL. “Early in the pandemic, there was a fear that the prevalence of myocardial damage or inflammation was very high – papers emerged suggesting up to a third of elite or competitive athletes showed evidence of inflammation,” he adds. “Over the course of time, with more and larger studies, that figure has been downregulated to between one and 1.5%.”

The threat is real, however. EF Education-Tibco-SVB’s Lizzy Banks was sidelined earlier this year with pericarditis – swelling and irritation of the tissue surrounding the heart – while Quick Step Alpha Vinyl’s Tim Declerq also missed the start of the Classics with the same complication.

Another worry early on was that people would develop long-term scarring of the lungs (‘fibrosis’) following Covid-19, but Hull says that this is “vanishingly rare” in athletes. Being fit and active is thought to offer some protection, with data suggesting a lower risk of severe complications. “Even the regular 10,000 steps a day target is protective,” adds Hull.

Clearer guidelines

While the risk of developing heart complications on your return to cycling after Covid-19 infection is relatively small, it will still impact one in 100 people. Fortunately, it’s possible to reduce your chances even further. An observational study from Washington University published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2021 found that the type and severity of Covid-19 symptoms tend to forewarn of the risk of developing heart issues. “Most athletic individuals who went on to get cardiac problems had had some sort of cardiac-related symptoms – chest pain, palpitations, a problem with breathlessness – when they were acutely unwell,” explains Hull.

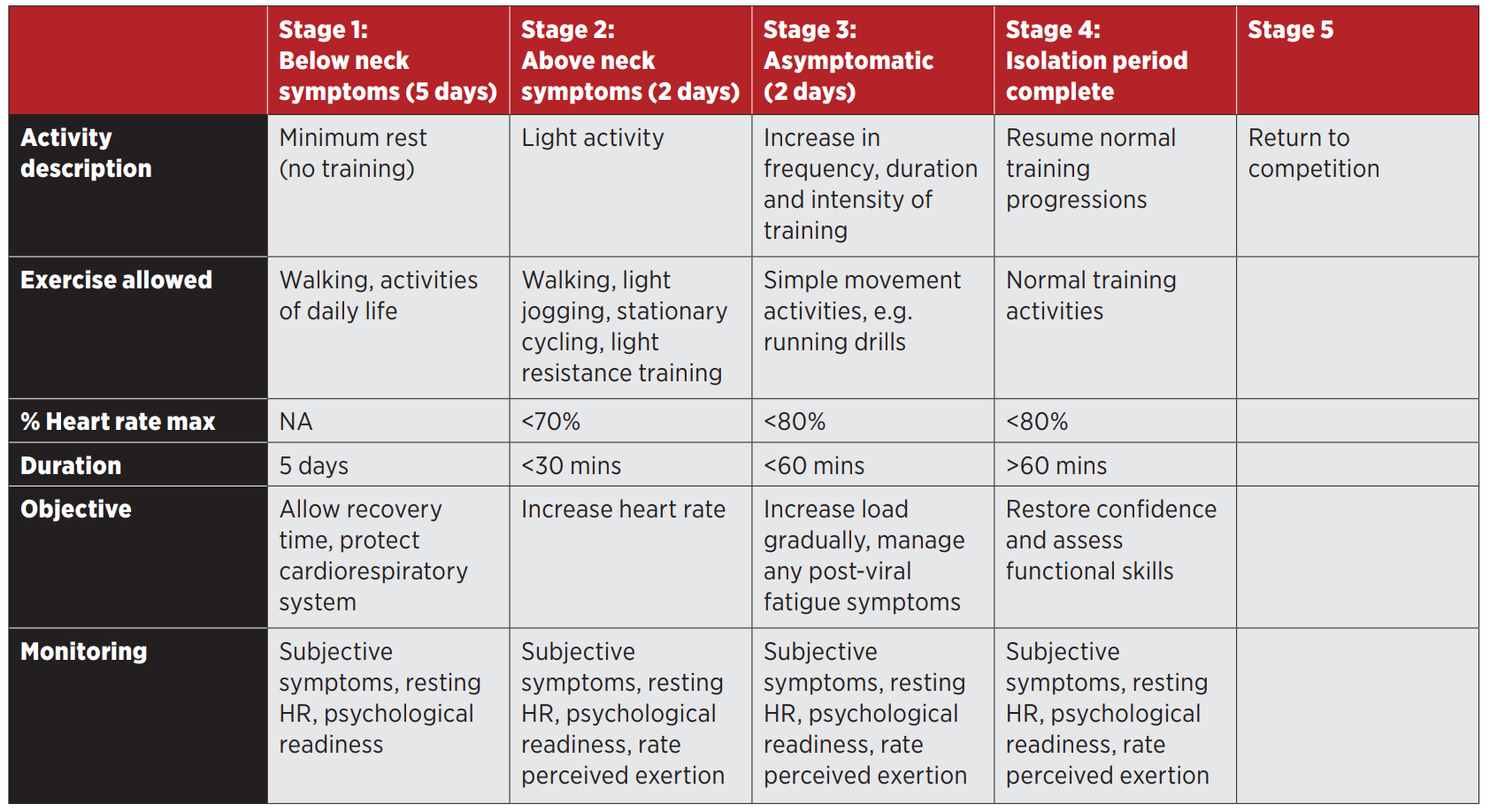

This research has informed the British Medical Journal’s latest ‘Graduated Return to Play’ guidelines, which enables you to tailor your recovery depending on the severity of your infection.

“Basically, if your symptoms are confined to the upper part of your respiratory tract – loss of smell, a snuffly nose, or flu-like symptoms just above the neck – it’s unlikely that you’re going to develop cardiac issues, and you can push on quite quickly back to full sport,” says Hull. “If you have chest or lower-than-the-neck symptoms or have been systemically unwell with high fevers, you need to be much more cautious. If you’ve got cardiac symptoms – chest pain or palpitations – you need to be cardiac-assessed before you return to the sport.”

The respiratory specialist cautions against rushing back to high-intensity training. “It’s about being realistic about what you can do,” he says. “The time frame of recovery needs to be managed appropriately. If seven days later you get back and you think, ‘I’m knackered, I can’t do it,’ that is an unrealistic timeline. In people who’ve had symptoms below the neck, it’s going to take four to eight weeks to feel better.”

Even if you had an asymptomatic case of Covid-19, the guidelines recommend taking a few days off from high intensity efforts. This is because the immune system is still fighting an infection, despite there being no apparent illness.

Tests at the Tour

As the above cases of Banks and Declerq show, the professional peloton isn’t immune from Covid-19. The most high-profile such examples were the positive cases at this year’s Tour de France, which accounted for 17 out of 40 withdrawals from the race – among them four-time Tour de France winner Chris Froome and stage winners Simon Clarke and Magnus Cort Nielsen - for Cort, Covid-19 positive heart rate and respiratory rate changes were revealed by Whoop.

There was controversy as well, with some riders returning positive results but allowed to continue, most notably stage nine winner Bob Jungles (Ag2r-Citroën), and UAE Team Emirates’s Rafał Majka.

“The decisions for athletes at the Tour were made by a triumvirate of the team doctor, a doctor on the UCI, and another independent expert who remains nameless, who made a decision about the risk and weighed those things up,” explains Hull, who advises a number of pro teams. One of the main factors determining whether a rider could continue or not was their cycle threshold (CT) score. A special PCR machine performs cycles to find the virus in a test sample. The number of cycles it has to perform before it finds the virus can determine whether the individual is currently positive or contagious. A CT score of above 33 cycles was taken to mean that a rider was no longer a risk to themselves or others.

Hull explains that this vetting was done on a case-by-case basis and highlights that there is a difference between an asymptomatic positive case of SARSCov-2 and Covid-19 – the latter being the clinical condition caused by the infection. “There are all sorts of different things and reasons why someone might test positive and actually not have any clinical sequelae [after effects],” he adds. “People can continue to test positive on a PCR test for many months after they’ve had the illness.”

For amateurs who test positive, though, Hull urges caution even if asymptomatic. “That could mean a full five-day break from the bike before gradually building up training or simply swerving any high intensity work for a couple of days, just to be on the safe side."

This article was originally published in the 8 September 2022 print edition of Cycling Weekly. Subscribe online and get the magazine delivered direct to your door every week.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Charlie Allenby is a freelance journalist specialising in cycling, running and fitness. He has written for publications including the Guardian, the Independent, T3, Bike Radar, Runner’s World, Time Out London and Conde Nast Traveller, and cut his teeth as staff writer for Road Cycling UK (RIP). He is also the author of Bike London: A Guide to Cycling in the City. When not chained to his desk, Charlie can be found exploring the lanes and bridlepaths of Hertfordshire and Essex aboard his pink and purple Genesis Fugio.

-

Review: Cane Creek says it made the world’s first gravel fork — but what is a gravel fork, and how does it ride?

Review: Cane Creek says it made the world’s first gravel fork — but what is a gravel fork, and how does it ride?Cane Creek claims its new fork covers the gravel category better than the mini MTB forks from RockShox and Fox, but at this price, we expected more.

By Charlie Kohlmeier

-

ROUVY's augmented reality Route Creator platform is now available to everyone

ROUVY's augmented reality Route Creator platform is now available to everyoneRoute Creator allows you to map out your home roads using a camera, and then ride them from your living room

By Joe Baker