'Cyclists have swallowed the idea that lighter is faster': Let's talk about eating disorders

Athletic ambition can tip into a toxic relationship with food. Chris Marshall-Bell investigates cycling’s dark underbelly

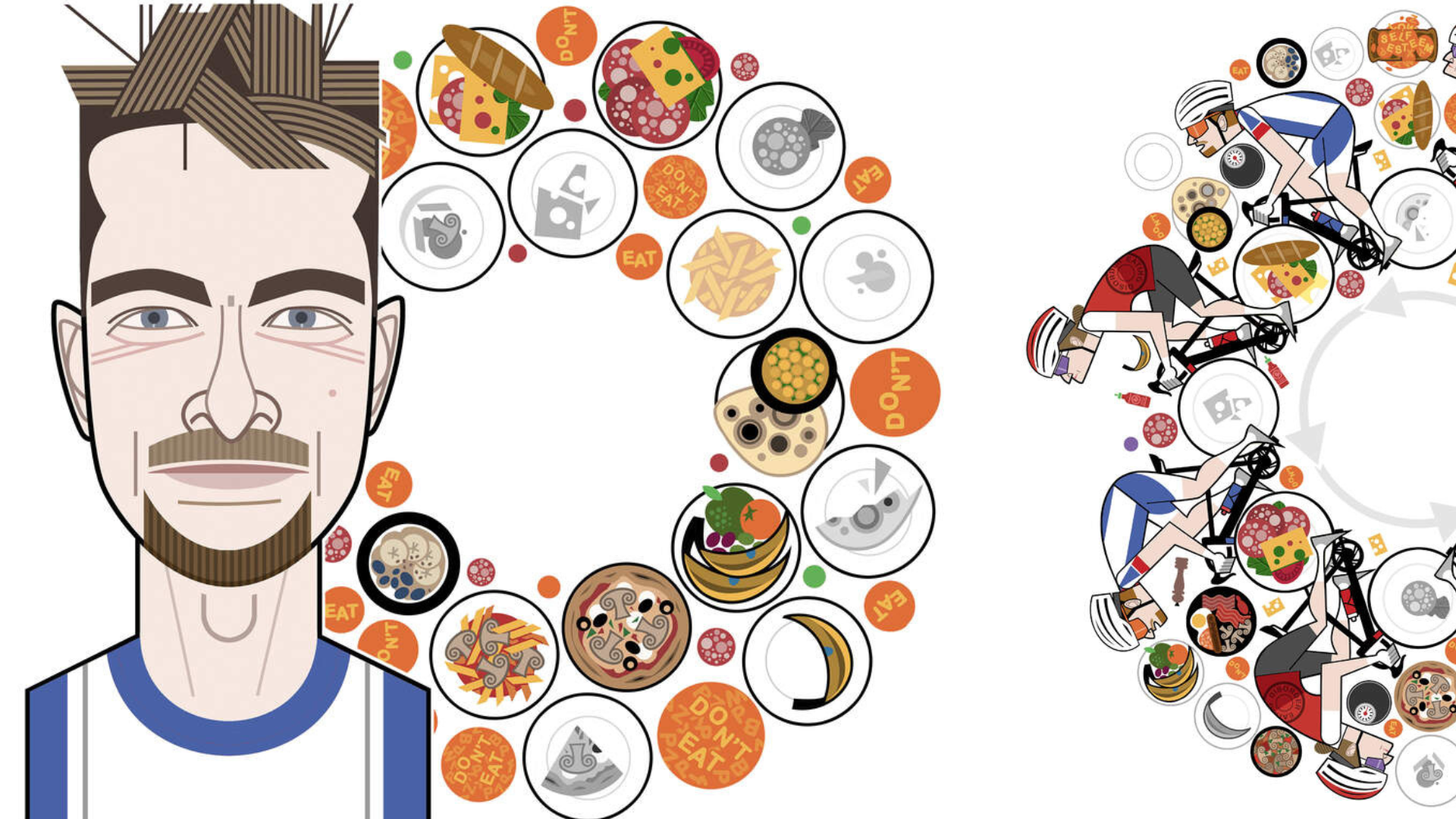

Jan Tratnik had been cycling for only three years when Quick-Step signed him to his first WorldTour contract in 2011. He was young, naive, inexperienced and keen to please those around him. “We did some tests [in training] and when we saw my watts per kilo [power produced divided by kilograms weighed], someone suggested that if I lost another two kilograms I could be really, really good on the climbs,” he says. “So I listened to them.” What Tratnik, then 20, didn’t know was that, at 65kg, he had no spare kilos to lose. “The truth was, I didn’t have much fat so it was really hard to lose this weight,” he recalls. “That’s how it started, because I didn’t know what to do.”

The ‘it’ he refers to was an eating disorder. “I reduced my eating to almost nothing to lose those extra two kilos, but it was really hard because I was losing muscle,” the Slovenian, now 34, continues. “I was hungry all the time – I was starving.” He was in the early stages of anorexia nervosa, an eating disorder and serious mental health condition characterised by a fixation on keeping weight as low as possible. “I was eating maybe one or two meals per day, but only small amounts.” As commonly occurs in anorexia, Tratnik also developed bulimia – binge eating followed by purging, forcing himself to be sick. “I couldn’t handle being starving, so I cracked and ate too much,” he says. “Being afraid to gain weight, it was a circle I couldn’t escape from.”

An eating disorder is a serious and complex mental health condition characterised by persistent disturbances in eating behaviours, thoughts and emotions related to food, body image and weight. There are three main types: anorexia, involving extreme food restriction and an intense fear of gaining weight, with the highest mortality rate of any mental illness; bulimia, characterised by excessive eating followed by purging and/ or intense exercise to avoid weight gain; and binge eating, frequently consuming unusually large amounts of food in an impulsive, uncontrolled way.

According to a systematic review published in 2019, the global prevalence of eating disorders rose from 3.5% to 7.9% over the previous 20 years. Women are disproportionately affected and account for approximately 75% of cases. Teenagers and those in their early 20s are most at risk, but these issues can develop at any age. Eating disorders often manifest concurrently with other problems such as alcohol and substance use disorder, depression, anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Of the underlying causes, psychotherapist Anna Hindwell points to “unresolved feelings related to low self-esteem, lack of worth, or repressed trauma,” adding that “disordered eating sometimes manifests as an attempt to cope with overwhelming emotions, providing a temporary sense of relief, comfort or structure in a chaotic emotional or environmental context.” The key point is, it’s not solely about wanting to be thinner or lighter – the underlying causes run deep.

Cyclists are at an increased risk

Studies have consistently shown that cyclists and other endurance athletes have a much greater risk of developing an eating disorder compared to the general population – but so sensitive is the topic that few ever talk about it. “In weight-sensitive sports, where body weight is important to performance, there seems to be a high prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating,” says Jack Hardwicke, a senior lecturer in the sociology of sport at Nottingham Trent University. In 2022, he co-authored a scoping review into eating disorders in competitive cycling, finding that 24% of female and 9% of male cyclists were at risk of developing disordered eating or eating disorders. Disordered eating, though less severe than an eating disorder, involves restrictive or compulsive eating. “Many cyclists are preoccupied with what they’re eating and how much, and that’s often at the expense of a healthy relationship with their body,” Hardwicke says, adding that “behaviours we see in professionals are mirrored and reflected among amateurs.”

Tratnik, who has just signed to Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe, remembers the torment he faced on a daily basis in his early-20s. “Life wasn’t easy. Everything happened so fast and I didn’t have any experience,” he says, referring to his rapid, three-year progression from starting cycling aged 17 to being a pro. After only 12 months with the team, Quick-Step failed to extend his contract and he returned to third-tier Continental level. “There were a lot of ups and downs, which almost ended my career,” he adds.

He was thrown one final lifeline in 2014 when Amplatz-BMC offered him a place. “No money, only a bike and kit. I decided to give it one last try,” Tratnik says. Finally, he began to feel better. “I wasn’t under so much pressure, so I gained weight,” he says. “I didn’t follow any nutrition plans; it was more or less eat what you want and do what you want. I rode my bike and ate what was on my plate – this helped me a lot.” His perseverance paid off after “four really hard years”, and by the end of 2014 he had fully recovered. In 2019 he returned to the WorldTour, with Bahrain-Merida, after a seven-year absence. How does he look back on that lost time? “It was hard,” he says, “but I’ve come through it mentally much stronger.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Hardwicke, a former second-cat racer, highlights why cyclists are susceptible to eating disorders: “Cyclists have swallowed the idea that lighter is faster,” he says. “Lean limbs with veins popping out are seen as a badge of honour among amateur riders, and that pushes people towards disordered eating behaviours.” Not uncommonly, weight loss attempts go too far. “Cycling puts a huge energy demand on the body, and if you’re not fuelling properly, things will break down,” Hardwicke continues. “If you’re chronically under-fuelling over months and years, using more energy than you’re consuming, you’ll suppress the immune system and seriously compromise your health.”

RED-S alert

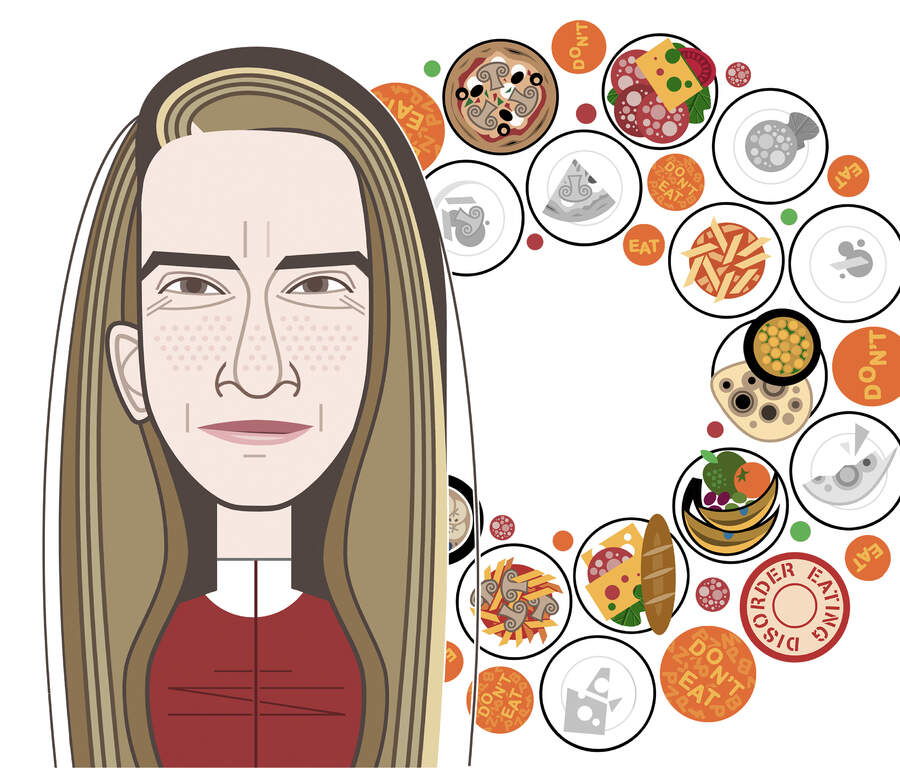

German rider Clara Koppenburg is another pro who has been through eating problems. The 29-year-old, who is rejoining Cofidis from EF-OatlyCannondale, recalls “a couple of years where I was too skinny and way too underweight.” Koppenburg exhibited symptoms of RED-S, relative energy deficiency in sport, where sustained calorie deficits hamper training and jeopardise health. “I was training for six hours [a day], but I wasn’t getting the balance right,” she says. The German says that, though she was not diagnosed with an eating disorder, her very thin appearance attracted negative attention. “I felt like a big stamp had been put on me: ‘this girl has an eating disorder, we can’t have her in this team’.”

Prioritising low weight can be to the detriment of a cyclist’s physical and mental wellbeing, with long-term implications. “They say if you’re low in body weight, with little fat, you can fly up the climbs, but you risk getting ill or injured,” reflects Koppenburg, “and for us females it can damage fertility prospects – and if I had destroyed my dream of having a family by not eating right, I’d never have forgiven myself.” After winning her own battle, she was determined to help others with eating problems.

While studying sports science at the University of Konstanz in Germany in 2018, Koppenburg wrote her bachelor’s thesis on the risk and awareness of eating disorders among female elite UCI cyclists. Of the 120 riders who filled in an anonymous survey, “32% had eating disordered tendencies; 55% reported having disordered feelings towards food; and more than half had been told [by teams] that they should lose some weight,” Koppenburg reveals. “The results were in line with what I expected,” she adds.

Koppenburg believes that awareness is improving at the top level of the sport. “Teams now favour riders getting more powerful rather than being shaped like an asparagus,” she says, “and we’re seeing more great climbers who aren’t very skinny.” Additionally, UCI teams do full medical check-ups on all their riders every winter, measuring weight, fat percentage, bone density and blood biomarkers, which often flags up RED-S. The support of team nutritionists and chefs is helping too. “We now know exactly how many carbs we have to eat, whereas six years ago we had no idea.”

Of course, these structural changes don’t protect amateur riders, nor do they guarantee the cultural shift needed. “I still think quite a large number of cyclists suffer from disordered eating habits,” Koppenburg says, acutely aware that a healthy relationship with food can be a hard fought struggle. She highlights the benefits of regaining a healthy balance. “You immediately feel stronger, can train harder and for longer, can recover well, and your mood is a lot better,” she says. “You want to socialise more, want to go out for dinner with friends, and life is just a lot easier.”

Tratnik urges riders to share their concerns and seek help. “You really need to believe it’s possible to pass through this,” he says. “The best thing you can do is talk about it, tell those close to you – you’re not alone in this.” He has learnt from his own mistakes. “I was too shy to tell people,” he says, reflecting that he is now “proud and happy” of having reset his relationship with eating and pulled through tough years without a pro contract to return to the sport’s top level. “I am not ashamed to talk about this now,” he says resolutely. “Everyone has some problems in their life, and this happened to me. Recovery does not happen overnight, it takes time, but it’s about believing, working hard and having support.”

Beware of the warning signs

Numbers, numbers everywhere we look. Many cyclists track their heart rate, weight and calorie intake on a daily basis. But data-fixation can be a contributing factor in eating disorders and disordered eating. “Daily monitoring and surveillance are a part and parcel of a pro’s life, but in my view it’s unhealthy,” says researcher Jack Hardwicke. “We see it among amateurs too: riders weigh themselves on a weekly basis, often turning down a drink or dessert because their weight is on their mind. There’s a tendency in sport towards obsessive behaviours, and calorie tracking apps feed into that.” Hardwicke also disapproves of the obligation on virtual racing platforms such as Zwift to input weight, even for under-18s.

If you find yourself preoccupied with calorie counting, body weight or shape, or you withdraw from social activities involving food, you may have an eating disorder or be at risk of developing one. Physical symptoms of disordered eating include weight fluctuations, fatigue, dizziness, frequent injuries and inconsistent performance. For women, a key symptom of RED-S is missed menstrual cycles. Other signs include anxiety or guilt around eating or taking rest, persistent dissatisfaction with performance despite achieving goals and rigid, all-or-nothing thinking about diet and training.

Disordered eating must be taken seriously: it not only hampers performance but can cause long-term health issues such as hormonal imbalances, reduced fertility, and weakened bones. A sensible first step, given the superabundance of data in cycling, is to take a step back from target-driven training. “We live in a world where everything is measured and quantified, but you have to remind yourself not to take things too seriously and remember why you’re cycling in the first place,” Hardwicke says. “Competition is great, but problems arise when the fun stops.”

Anyone who thinks they may have an eating disorder should visit their GP as soon as possible. Advice is also available from the eating disorders charity Beat: 0808 801 0677.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

A freelance sports journalist and podcaster, you'll mostly find Chris's byline attached to news scoops, profile interviews and long reads across a variety of different publications. He has been writing regularly for Cycling Weekly since 2013. In 2024 he released a seven-part podcast documentary, Ghost in the Machine, about motor doping in cycling.

Previously a ski, hiking and cycling guide in the Canadian Rockies and Spanish Pyrenees, he almost certainly holds the record for the most number of interviews conducted from snowy mountains. He lives in Valencia, Spain.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

-

'It took everything' - Puck Pieterse outclimbs Demi Vollering to win La Flèche Wallonne

'It took everything' - Puck Pieterse outclimbs Demi Vollering to win La Flèche WallonneDutch 22-year-old shows Classics pedigree with first one-day victory

By Tom Davidson

-

Tadej Pogačar flies to dominant victory at La Flèche Wallonne

Tadej Pogačar flies to dominant victory at La Flèche WallonneSlovenian takes second win at Belgian classic ahead of Kévin Vauquelin and Tom Pidcock

By Tom Thewlis