fitness: Drink aware

drink aware 2 - chris watson

17th November 2010 Words: Dave Bradford Illustrations: Chris Watson

Everyone likes a drink, but how badly does a heavy session impact on your cycling fitness? Dave Bradford lifts the lid on hitting the bottle.

It’s Friday evening and you’re in the pub unwinding after another long week at work. You have a big ride planned for Sunday, but there’s plenty of time to recover before then, right? You’ve sunk a couple of drinks already and your pal’s just getting to his feet to fetch the next round.

It’s a familiar crossroads. Do you draw a line and stop drinking or surrender to alcoholic oblivion? Call it quits and you’ll be barracked for being a party-pooping lightweight; carry on and there’s no telling where or when the evening will end — or what state you’ll be in come the morning.

Never mind tomorrow, though, how will you feel on Sunday? It’s time to answer that nagging question: does getting sloshed harm your cycling fitness?

Understanding the effects of alcohol on athletic performance is not a major preoccupation among sports scientists. This is probably because most professional sportspeople steer clear of booze or drink very little.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

As for the rest of us, we are more rounded, sociable beings, aren’t we?

It takes a lot of commitment to become an accomplished drinker and it’s quite clear that if you drink moderately, keeping your intake within government guidelines (a couple of drinks a day, at most), you won’t damage your health.

In fact, one Dutch study found that moderate drinkers live on average five years longer than their abstaining counterparts — a bonus credited to the heart-healthy benefits of red wine.

So, wine-sipping cyclists are in the clear, which includes all those French pro riders who love to boast about how they savour a glass of Burgundy with their dejeuner. Good for them, but the occasional glass of wine just isn’t the British way when it comes to drinking.

We’re far more dedicated; we treat drinking as an endurance sport. Does our habit of downing a bellyful really hold us back when we finally swap our Grolsch for Gatorade and head for the hills? It depends who you speak to.

A sin to binge?

Cyclists come in all shapes and sizes, and the same is true among those who like a drink; they don’t all have bloated bellies and ruddy faces. Genetic factors play a role in determining how efficient our bodies are at processing alcohol, so there is no one-size-fits-all rule about how much is too much.

What we do know is that alcohol is one of the most calorie-dense substances we consume, containing 7kcal per gram — second only to fat (9kcal per gram). Of course, you don’t see the calories in your glass or perceive them as weight but they’re in there, make no mistake.

There are about 200kcal in every pint of regular-strength lager and about 120kcal in every glass of wine. Opt for cider and you’re glugging down 240kcal — a whole Mars bar’s worth — every pint.

“That doesn’t bother me,” you might retort, “I need the extra calories to fuel my epic training rides.” Even if your energy needs are huge, there’s a hitch: your body is unable to convert alcohol into the most valuable source of energy for exercise (ie, glycogen).

This means alcoholic beverages are of very limited value for carb-loading. Granted, the sugar used to sweeten these drinks provides some useful fuel but most of it gets used up swiftly — because another effect of alcohol is that it inhibits glucose production in the liver.

As a result, your blood sugar level plummets and your body is forced to send out a mayday signal for additional supplies, which is why you crave sugary drinks and energy-rich food when you’re hungover.

“After a drinking binge, you’re chronically malnourished and in dire need of hydration and glucose,” explains sports physiologist Nick Tiller. “You have gained no glycogen from the binge, and having an energy source like alcohol in the system is never good for recovery — particularly as it may interfere with carbohydrate metabolism.”

Most of the alcohol you consume is broken down to form a substance called acetate — an unhelpful compound that skips ahead of fat in the energy-source queue. So, in the short-term you burn less fat and, in the long-term, may find yourself putting on weight.

Although the link between beer and rotund bellies is somewhat exaggerated, the cumulative effect of extra calories plus reduced fat burning is inescapable. Excess body-fat doesn’t just conceal your six-pack; flabby bellies are linked to decreased insulin sensitivity — leading to poor blood-sugar control and, in the worst case scenario, type-two diabetes.

Never mind the unsightly stomach; for an endurance athlete, disrupting the body’s ability to store and use energy is a big risk to take.

Drunken dozing

After a night on the tiles, you invariably awake in the wee small hours with a dry mouth and a raging thirst. It’s because all that alcohol you drank suppressed your body’s production of anti-diuretic hormone, which usually tells the kidneys to reabsorb water; instead, they flushed it through and you peed it out. Of course, re-hydration can be achieved rapidly but even a minor dip could adversely affect cycling performance.

“Just one alcoholic drink can cause a slight drop in plasma volume [the liquid component of blood] through dehydration,” warns Tiller. “The lower your plasma volume, the lower your blood volume and the harder your heart has to work to pump the same volume of blood to working muscles.”

Having woken up needing a drink, you have fallen victim to another of the pitfalls of drinking — disrupted sleep. In fact, this is potentially the most damaging impact of alcohol on your cycling fitness. Everyone needs sleep but cyclists are more dependent than most on its recuperative powers.

There is no better form of intensive recovery from exercise than sleep, and insufficient shut-eye has been shown to deprive the body of tissue-building growth hormone. Most of us are optimally refreshed by seven to eight hours’ sleep each night, but what matters just as much as total duration is the quality and pattern of sleep.

Basically, we need to kip soundly and solidly to achieve the correct proportions of dreaming, non-dreaming and deep sleep. Although alcohol helps us drop off to sleep, it makes us sleep restlessly and disrupts the sleep cycle; we don’t get nearly enough dream (REM) sleep.

The detrimental effects of drunkenly dozing, rather than quality sleep, are psychological as well as physical.

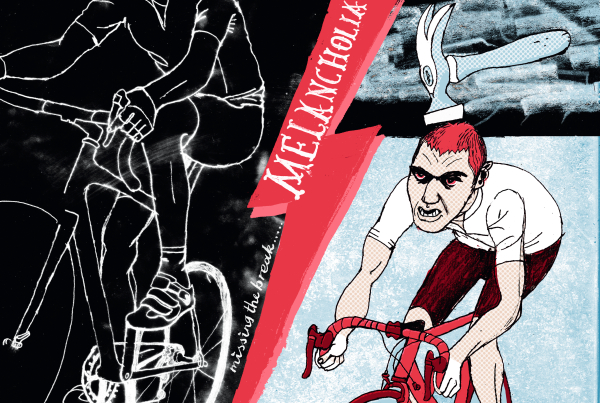

Things can only get worse; your mood is not yet at its lowest ebb. The real melancholia will kick in after every trace of alcohol has left your body. Then you may experience what the writer Kingsley Amis coined the “metaphysical hangover”; you feel anxious, sad and pessimistic — a dark mood which may endure into the next day.

Sports psychologist Dr Victor Thompson (www.sportspsychologist.co.uk) evaluates the possible impact on your cycling: “With a drop in mood, your thoughts will be more negative — predicting a difficult day in the saddle, a poor ride or race performance. This leads you to putting in less effort, being negative about your chance of staying with the pack and of holding a certain pace.”

In addition to feeling glum, you may also find yourself daydreaming. “Your concentration will be affected, with a greater chance of missing breaks, changes in pace and hazards in the road. In short, you’ll do less well than you could have.”

The morning after

So, you finally heave yourself out of bed, with grim determination to ignore the hangover and stick to your riding commitment. The first question for your addled brain to consider is: what to eat for breakfast?

Contrary to the marketing hype that accompanies a plethora of hangover cures, there is no miracle cure for hangovers; you simply need some easily absorbed sugars to get your blood glucose back to normal and some slower-release carbohydrates to fuel your ride. Some orange juice, a glass of water and a bowl or porridge will do the trick.

A sensible breakfast will not, however, ensure that your stomach feels fine. Too much alcohol, particularly large quantities of beer, often leads to digestive issues, causing food to pass through too quickly and irritating the bowel. Without dwelling on the fetid details, it’s worth noting that the consequences are potentially more serious than having to make an extra toilet stop or two.

Alcohol may interfere with the digestive system’s ability to absorb nutrients, potentially leading to deficiencies in certain minerals and vitamins — plus an increase in cell-harming free radicals. As a cyclist, your need for a whole range of nutrients is higher than that of an inactive person, and any shortfall in antioxidants may weaken your immune system, leading to sub-par performance and illness.

OK, so we can’t ignore the fact that cyclists who go out and get hammered on a regular basis are seriously jeopardising their fitness (and general health). Heavy drinking puts huge strains on body and mind, and thereby counteracts the positive benefits of exercise. In a nutshell, excessive alcohol disrupts your body’s ability to accrue the benefits of rigorous physical activity.

But it’s not all bad news. Moderate drinking carries none of the aforementioned risks; having the odd pint of beer or glass of wine will not harm your fitness levels. Furthermore, several well-publicised studies have shown that moderate social drinking helps to relieve stress, which is a boon to body as well as mind.

In other words, being sociable and having a balanced lifestyle that allows you to let your hair down complements rather than hinders your resolve to keep fit. If the occasional drink keeps your stress levels low, then it is almost certainly a net benefit to your well-being and, in turn, your cycling.

“Drinking isn’t all bad,” concedes Dr Thompson. “It helps to quieten the fears and, if you’re with other people, helps to relieve stress and anxieties, be they related to your cycling or not — a pleasant distraction. Include a little alcohol and maybe you’ll have a better weekend overall.”

Booze by numbers

550 Calories — in a bottle of white wine.

21Units per week — Government’s recommended maximum intake of alcohol for men.

240Calories — in a pint of cider (roughly equivalent to a Mars bar).

7-8Hours per night — the sleep you need… but don’t end up getting when you drink.

7Calories — in one gram of alcohol.

1Drink — the amount of alcohol it takes to cause a drop in hydration levels.

14Units per week — Government’s recommended maximum intake of alcohol for women.

2.8Units — in a pint of five per cent volume beer.

3Hours — the time it takes the body to get rid of the alcohol in one pint of premium-strength beer

2,600Calories — consumed during a typical British binge (six pints of beer, packet of peanuts, doner kebab and chips)

case study

The pro triathlete

‘Drink is the devil’: Will Clarke, 25, is a double British triathlon champion who has his sights set on a medal at the 2012 London Olympics.

How much do you drink?

“When I am training hard, I won’t touch it because it means I can’t be consistent with my training. I certainly won’t be able to keep up with the best if I drink regularly.”

Why do you abstain completely?

“I think alcohol is the devil for athletic performance. As everyone knows, it’s a depressant, so it doesn’t make you feel great the next day [after drinking]. Personally, it makes me feel really lethargic, heavy-bodied, and it seems to make me put on weight faster than anything else.”

Would you advise all cyclists against drinking?

“For a non-professional athlete, I think it’s fine to go out and drink. Having a few definitely doesn’t do any harm — and it’s part of our culture! However, I would recommend not drinking during the week before a race. Drinking a lot during hard training will run you down or make you feel rubbish; you won’t be performing optimally.”

So, you do enjoy the occasional tipple?

“I have around three weeks off at the end of the year, when I do what I want, eat what I want, go where I want, and drink as much as I like — that’s when I get it out of my system. A couple of times during the season, after great races, I go out into town to celebrate. It is incredibly relaxing, and it’s fun to celebrate after a good performance and let your hair down.”

case study

The club cyclist

’I used to drink six pints every night’: Johan Stegers is a 47-year-old cyclist and member of East Sussex club Lewes Wanderers. He competes in time trials (10-mile PB: 23mins) and the occasional fourth-category road race.

How much do you drink?

“I have cut down dramatically. Since January 2010, I’ve been drinking about 20 units per week, in two or three hits — each time, as a binge. I don’t muck about, I drink for the hit. I drink early in the week to allow full recovery for a Sunday race.”

Is drinking important to you?

“Yes, but I wish it wasn’t. Every now and then, I feel the need to escape from life’s stresses. The hit from cycling or, more specifically, from exercise, is far more important than the hit from drink. Racing, although very stressful, is the ultimate form of exercise and I get a massive hit from it. It would have been better if I’d never discovered alcohol. As it is, I have to battle with the stuff; once you learn to use it as a crutch, it’s got you. An after-race drink can so easily turn into a week-long bender.”

Why are you so careful about not drinking on the days before a race?

“Alcohol has a damaging mental effect on me. If I have a serious [drinking] session on Friday afternoon, the effects linger on past the hangover stage and into Sunday. I find it makes me very apathetic. Even with an adrenaline rush, I’d still perform below par.”

What have been the effects of reducing your intake?

“I was overweight. In December 2009, I was tipping the scales at 88kg. Keeping a food diary told me that, from the 70 to 80 units of alcohol I drank each week, I was taking on 1,200 calories every day — plus ‘drink-fuelled’ snacks, adding up to literally thousands of calories. I lost 7kg over about two months. Cutting down on the booze also improved my mental state and sleep, allowing me to wake up early and get in 20 hard miles before work.”

This article first appeared in the September 2010 issue of Cycling Active magazine

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

-

How do the pros train? Noemi Rüegg's 26 hour training week

How do the pros train? Noemi Rüegg's 26 hour training weekWinner of this year’s Tour Down Under, the EF Education-Oatly rider is a climber whose talent is taking her to the top

By Chris Marshall-Bell

-

Save £42 on the same tyres that Mathieu Van de Poel won Paris-Roubaix on, this Easter weekend

Save £42 on the same tyres that Mathieu Van de Poel won Paris-Roubaix on, this Easter weekendDeals Its rare that Pirelli P-Zero Race TLR RS can be found on sale, and certainly not with a whopping 25% discount, grab a pair this weekend before they go...

By Matt Ischt-Barnard