Fuel like a pro: The scientific strategies that maximise performance

We all know that food equals energy, but just how scientific in your fuelling do you need to be to maximise cycling performance?

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“You take this application device,” says Graeme Obree to the BBC Panorama reporter, waving a cutlery knife in the air, “scoop the jam onto the sandwich and spread it in an even manner like so” – and with that his fuelling ‘secret’ is revealed. In characteristic deadpan style, the Scotsman is making the point that carbohydrate is carbohydrate and serves the same function in whatever form, simple sarnie or supposedly advanced drink formula. For Obree, putting a diagonal slice through two slices of bread is as cutting-edge as any cyclist’s nutrition needs to be. “He doesn’t use sports drinks,” booms the voiceover. “His energy-booster is nothing more sophisticated than a jam sandwich and plain, old-fashioned water.”

That BBC documentary, providing a highly sceptical take on sports drinks, was broadcast nearly a decade ago, but it always sticks in my mind when the topic of fuelling comes up. Not because there was anything revolutionary in Obree’s dismissal of fancy carb products, but because of the paradox it so neatly encapsulates. Yes, the carbohydrates in a £1 jar of jam are basically the same, in terms of their nutritional value, as those in a £10 pack of sports drink – and that’s a valuable truth for any leisure cyclist seeking to save money while training for long rides. But at the same time, it’s an oversimplification and potentially misleading for serious racers who want to optimise their fuelling for high performance.

As a recreational rider and has-been distance runner, I’m in the former camp: I don’t need to invest time, expertise or money on perfecting my fuelling, as it wouldn’t make any meaningful difference to my low-stakes, short-duration racing. Counting carbs or calories would be overkill for me, and a pre-race jam sandwich will do. But what about for an ambitious, improving rider who wants to be the very best they can be in multi-hour, even multi-day races? How important is it for an athlete in this altogether higher-stakes position to take a scientific approach to their fuelling? It was time to take this question to a specialist team of scientists for whom pro-cyclist fuelling research is their bread and butter – if not their bread and jam.

Callum McQueen in the SiS lab at Liverpool John Moores University

McQueen’s pro coronation

'Train low' protocols

We asked Prof James Morton if low-carb training is really worthwhile and advisable for amateur riders as well as pros.

“I’ve spent the last 10-15 years of my research career looking at carbohydrate periodisation,” he said. “There is a definite rationale for doing it, regardless of whether you’re amateur or professional. It activates molecular signalling pathways, which instruct your muscles to make more mitochondria and become more aerobically trained, shifting your lactate threshold higher. For a given absolute intensity, you’ll be using more fat and less carbohydrate, meaning that as you get towards the end of a long ride you’ll have more carbohydrate left in the tank.”

A note of caution: low-carbohydrate training should be conducted very carefully, ensuring that your overall intake is keeping up with expenditure, so as to avoid the serious risk of relative energy deficiency (RED-S). The intensity of your ‘train low’ rides should be low to moderate (Zone 1 and 2) and generally no longer than 90 minutes. Your other rides, especially the high-intensity ones, should be carried out in a fully fuelled state. Most riders should not do more than two low-carb rides per week.

Pre-breakfast ride

1. Postpone breakfast

2. Ride with low glycogen, e.g. commute to work

3. Refuel after ride

Double session day

1. Eat normal breakfast

2. Ride in the morning to deplete glycogen stores

3. Eat a low-carb lunch

4. Ride in the afternoon with low glycogen

5. Refuel after second ride

Long ride without fuelling

1. Eat normal breakfast

2. Ride for five or six hours without fuelling

3. Refuel after ride

Sleep low, train low

1. Eat low-carb evening meal

2. The next day, postpone breakfast

3. Ride with (very) low glycogen

4. Refuel after ride

Fuel for the work required

This one requires more planning, as Morton explained: “This is the model we’ve coined at Liverpool John Moores University: riders adjust their intake day by day, meal by meal, depending on what they have scheduled for the next day.”

Our elite cyclist guinea pig – and a regular presence in these pages – is Callum McQueen. Getting his fuelling spot-on is critical for 21-year-old Callum because he is aspiring to take his cycling all the way to the top level – and he’s on track, having just signed his first professional contract with Continental outfit Yoeleo Test Team p/b 4Mind. We sent him to Liverpool John Moores University to be assessed by professor James Morton, who heads up research for nutrition brand SiS and was lead nutritionist at Team Sky between 2015 and 2019. When it comes to designing fuelling strategies for toplevel cyclists, Morton’s track record speaks for itself.

Callum was to be put through the same testing protocol Morton uses to assess WorldTour riders preparing for a Grand Tour. The technical term is “substrate utilisation” – working out exactly how an individual rider turns fuel (primarily fat and carbohydrate) into pedalling energy. This information can then be used to calculate precisely how the rider should fuel during races but also, just as importantly, during training to enhance physiological adaptations. The aim for a high-performance cyclist is to make their body as efficient as possible at using the fuel available to it. To use a motoring analogy, the goal is maximum miles to the gallon without compromising topend performance.

On arrival at the lab, the first step for Callum was to get measured: height, weight and body composition. Within minutes the results were in: 185cm (6ft 1in), 66.3kg (10st 6lb) and 12.5% body fat. As you would expect of a full-time rider training 20-plus hours per week, Callum is skinny enough to cause his mother sleepless nights. But what does prof Morton think from a scientific perspective – what is optimum for an elite cyclist? “If you want to be a climber, it’s all about power-to-weight, and at the highest level, one to three kilos can make a huge difference in terms of climbing performance,” he says. “I’ve seen riders who, having been not at all competitive at 70kg, dropped to 67kg and were suddenly very, very competitive.”

The next step for Callum was to lie inside a sealed bubble known as a calorimeter to measure how many calories his body was using at rest, his resting metabolic rate (RMR). This produced a figure of 1,744kcal – that’s the amount he would have to consume each day to stay at the same weight if he did no activity at all. But Callum burns thousands of calories in training every week, so what is the relevance of RMR? “Firstly, it’s very useful for weight management,” says Morton, “because you should never consume less than your RMR. Secondly, assessing your RMR is a good indicator of relative energy deficiency. If your measured RMR is significantly different from your predicted rate, it shows that your metabolism is slowing down.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Estimated RMR is calculated using an algorithm, based on height, weight and age – to find yours, simply google “RMR calculator”. In Callum’s case, his estimated RMR matched the measured figure almost exactly, confirming that he had been fuelling adequately and was not in a state of energy deficiency. So far, so good, but let’s imagine Callum wanted to lose a kilo or two, how would knowing his RMR help him? “By recording his energy expenditure on the bike, he could add this figure to his RMR,” explains Morton. “He would also need to allow another 10% of his calorie intake for the thermic effect of food – the energy cost of digestion – and then he would know his total daily energy expenditure. To lose weight, you need to be consuming less than you’re expending.”

Hang on, though. What is a safe calorie deficit for a high-volume cyclist, given the risk of relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S)? “There are no golden rules here,” says Morton. “Every athlete is different. I’ve seen WorldTour cyclists accrue calorie deficits of 1,500-2,000kcal per day – but of course you can’t do that for a long period of time.” For amateur riders without nutritionists guiding them, Morton suggests a maximum daily deficit of 500kcal. “You can be a little more aggressive at times and go up to 1,000kcal – but the trick is that you don’t do the same every day.”

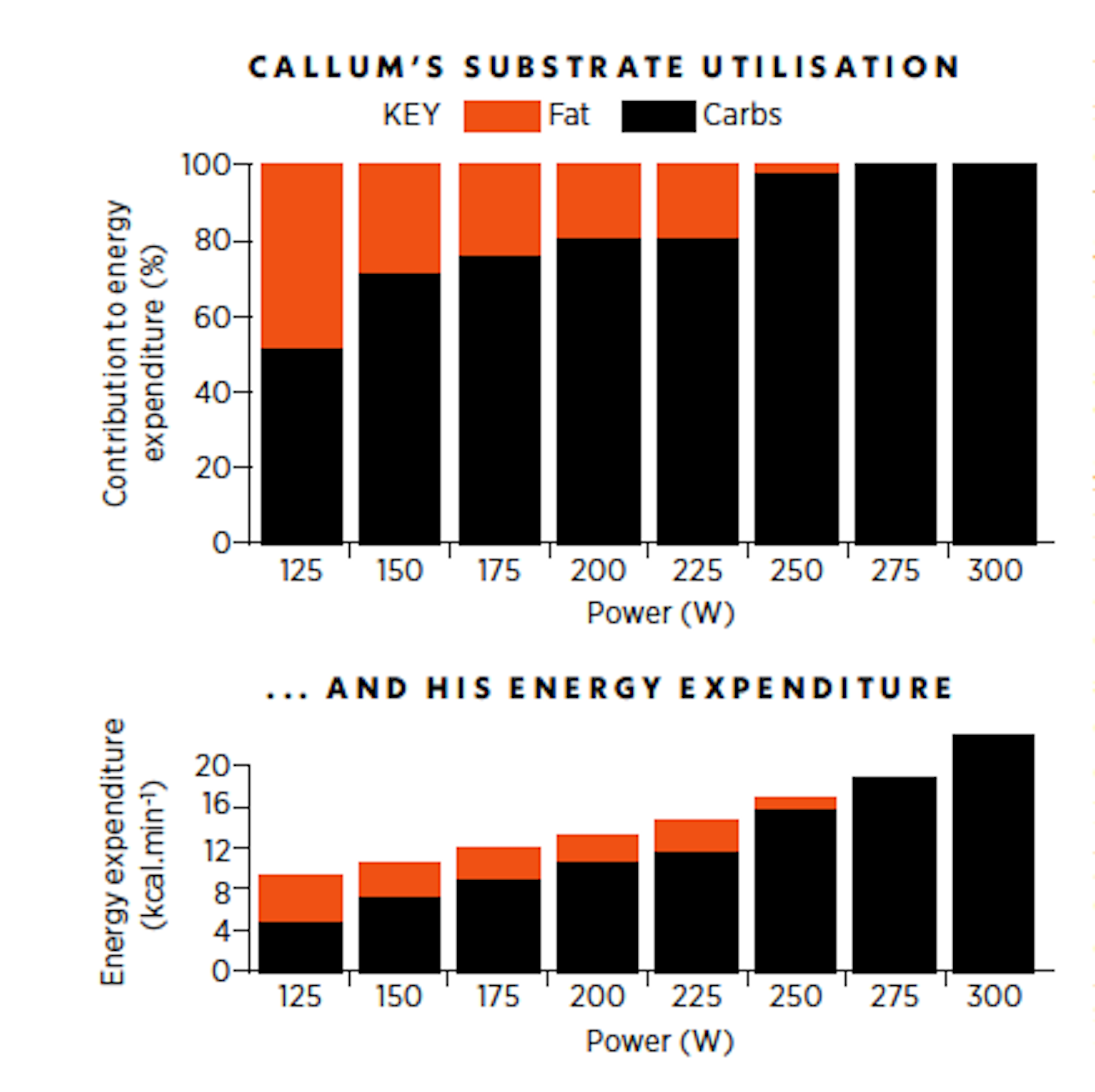

There is an important caveat to add here. The type of weight loss Morton is outlining is not geared towards health; it is solely about maximising power to weight ratio – and it is not sustainable all year round. “Most of the top guys stay at their optimal race weight for two races a season only,” clarifies Morton. “Seven to 10 days after the Tour de France, they’ll be two to three kilos heavier again. I think that is the best way to do it.” Fat vs carbs No more lying around; it was time for Callum to begin the pedalling part of the testing. He was set to work on an incremental ramp test while hooked up to equipment precisely measuring his energy usage – not just calories but also the fat and carbs being burnt. This showed that while spinning at 125W Callum was using 9.3kcal per minute, from an almost 50/50 split of carbs and fat, whereas while pushing hard at 300W he was using 22.8kcal per minute, 100% from carbohydrate. It’s fascinating data, but again I wanted to drill down into its practical usefulness. How would these figures really help, for example with weight loss?

The calorimeter is used to establish Callum's resting metabolic rate (RMR)

“If you’re trying to lose weight, you’re usually trying to lose body fat,” says Morton, “so you want to be oxidising fat as a fuel, but you also need to be in an energy deficit.” While you could ride at a low intensity for maximal fat-burning, this would mean burning energy much more slowly, making it harder to accrue a deficit. It’s generally best for weight loss, therefore, to ride at a moderate intensity, burning some fat while keeping the rate of overall energy expenditure reasonably high. The point at which the body switches over from using a mix of carbs and fat to solely carbs corresponds to the lactate threshold. At this level of intensity, breaking down fat is too slow a process and cannot keep up with the energy demand; fast-burning carbs are the only option. For Callum this occurs at around 250W; the fat tap is closed and the carb burners fully opened. This is a key benchmark for Morton because the higher the lactate threshold, the more carbs are conserved. “To improve his performance, Callum needs to shift his fat-oxidation curve,” says the scientist, “so that he is burning more fat at higher intensities. At 250W he’s burning 100% carbohydrate. In a WorldTour cyclist, that switch over to carbohydrate happens at a much, much higher power.” Morton provides an arguably unfair point of comparison: Chris Froome in his Tour-winning heyday, whose lactate threshold was an eye-popping 430W.

Making the most of fat stores

The tests showed that, at his more relatable lactate threshold of 250W, Callum was burning three grams of carbohydrate per minute – that’s 180g per hour – which means he is rapidly emptying the tank. A rider of Callum’s body mass is able to store around 500g of carbohydrate (2,000kcal of energy), so at this intensity he would run out after less than three hours’ riding. His fat stores, on the other hand, are practically infinite: his 8.3kg of body fat is enough to provide 65,000kcal of energy – but that’s of no use at 250W because, as we know, he’s burning solely carbs. He has two options: slow down and switch to fat-burning or replace carbs by eating and drinking on the bike.

In the latter case, studies have shown that athletes can absorb up to 120g of carbs per hour from fuelling on the bike. Morton’s favourite example of this maximal intake in action is Chris Froome’s 80km solo break to win Stage 19 of the 2018 Giro D’Italia. “If he had not fuelled during the ride with 90-100g [carbohydrate per hour] – the most he’d ever fuelled on the bike in his career – he would have emptied the tank after three and a half to four hours,” Morton proudly recalls the masterplan. “He could not have ridden like that if he hadn’t fuelled so aggressively.”

Let’s assume Callum is able to replace almost as much as Froome, 80g per hour, while sustaining his 250W effort; this still leaves him with a sizeable shortfall of 100g per hour. In a long, hard race he may still run out of carbs despite his best efforts to eat and drink plentiful amounts. Hence Morton’s insistence on raising the lactate threshold – training the body to burn fat and preserve carbs even at relatively high power outputs. The question is, how?

The results show Callum switches over to burning almost 100% carbohydrate by the time he hits 250W

Raising the bar

“You can target either intensity or volume to improve the threshold,” says Morton. “An endurance athlete without doubt needs high volume.” When I point out that Callum is already doing 20 hours per week, Morton is unimpressed. “A good WorldTour cyclist is doing 30 hours a week,” he shrugs. Which specific sessions best target the lactate threshold? “It’s about the balance of sessions,” says Morton. “You need to apply the stress to signal to the muscle to create more mitochondria. The reality is, you can do this multiple ways; a six-hour low-intensity ride could send the same signal as a two-hour higher-intensity ride.”

Replacing carbs on the go

When it comes to fuelling on the bike, how to push the upper limits? We asked Dr Trent Stellingwerff, director of performance solutions at the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific

Is a max intake of 120g of carbs per hour on the bike a realistic target for most cyclists?

There is evidence to support 120g as a theoretical upper limit, yes, but you could write a whole PhD trying to validate that number. There is more and more evidence that the gut is trainable, both in psychosomatic as well as physiological ways. To get to the upper level of intake probably relies on hitting a sweet spot between exercise intensity, duration and mode – you’re never going to absorb 120g per hour in a one-hour, high-intensity race.

How to go about training the gut?

Ideally on a moderately warm day, start with 60g of carbs per hour in 600ml, a 10% solution. Over multiple long rides gradually increase your intake until you experience adverse GI side effects. Play around with carb concentration, drinking frequency, how much you drink each time you grab your bottle, and find a routine that works well. Remember that the GI tract works on a circadian rhythm – that morning’s coffee, breakfast and poop matter a lot!

In terms of fuelling products, the biggest buzz seems to be around SiS’s latest Beta Fuel and Maurten’s hydrogel range – what’s special about these?

There is a landslide of data showing that glucose-fructose blends definitely beat glucose alone, in terms of absorption rate, oxidation rate and performance. I was involved in a huge review of this topic, and the evidence is solid. There is a little evidence that a 1:1 blend of glucose-fructose might be slightly better than a 2:1 blend [SiS Beta Fuel is a blend of glucose in the form of maltodextrin and fructose at a ratio of 1:0.8]. The Maurten product uses an encapsulated delivery system, meaning the carbs get released a little further down the GI tract – there is published data showing increased gastric emptying at rest, as well as one paper showing a slight increase in carbohydrate ox

It’s not only training intensity that matters but also the amount of fuel available to the body. “Callum would probably benefit from doing a lot of carbohydrate periodisation,” says Morton. “I haven’t seen his training log but from the test data he looks like someone who fuels his rides consistently.” The goal of carbohydrate periodisation is to stimulate adaptations by varying the fuel reserves available – deliberately riding in a depleted state on selected rides while fully fuelling other sessions. There are several ways to do this (see box), but with a core guiding principle.

“You need to keep the muscle guessing throughout the year,” explains Morton, “by alternating between sessions that target fat oxidation, teaching the muscle how to use fat as a fuel, and sessions where you’re fuelled and teaching the muscle how to use carbohydrate as a fuel.” At this point Morton draws on another motoring analogy. “Think of it like a six-gear car: if you’re doing low-carb rides all the time, you’ll be very good in gears one to three, but as soon as you need to ride fast and go hard, you won’t know how to use gears four, five and six.”

As we have seen, fuelling at the top level has come a long way since settling for a jam sandwich and hoping for the best. If, like Callum, you want to squeeze out every drop of your potential over long-duration races, then approaching your fuelling with scientific precision has proven value. It will allow you to train your gut for maximal on-bike intake and stimulate adaptations in your body to make it frugal in its use of precious carbs while fully exploiting plentiful fat stores. It’s a fastidious approach requiring monk-like devotion, accuracy and caution – probably a step too far for most amateurs – but if you want to perform like a pro, you need to fuel like one too.

This article was originally published in the 27 January 2022 print edition of Cycling Weekly. Subscribe online and get the magazine delivered direct to your door every week.

David Bradford is senior editor of Cycling Weekly's print edition, and has been writing and editing professionally for 20 years. His work has appeared in national newspapers and magazines including the Independent, the Guardian, the Times, the Irish Times, Vice.com and Runner’s World. Alongside his love of cycling, David is a long-distance runner with a marathon personal best of 2hr 28min. Diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in 2006, he also writes personal essays exploring sight loss, place, nature and social history. His essay 'Undertow' was published in the anthology Going to Ground (Little Toller, 2024). Follow on Bluesky: dbfreelance.co.uk