Improve your power fast!

Want to be a successful road racer? Sure you do, who doesn't? The problem is, in order to achieve your goal you're going to need to be a half decent sprinter.

Look at races the length and breadth of the country and the riders getting the points are those that emerge from the pack at the end of a race and get across the line in the top few places. Countless hundreds of riders have the capacity to finish the race in the bunch, very many fewer have the ability to emerge from it in the final few hundred yards and trouble the scorers.

The problem is, training to improve your sprint is notoriously difficult. Riders are very prone to accepting their lot when it comes to their sprint prowess, often with the misguided excuse that "I wasn't born with sufficient fast-twitch muscles fibres to compete with those guys, so I'll just sit in the bunch thanks very much".

The good news is that, sufficient Type IIs or not, you can improve your sprint capabilities if you are prepared to work hard. So, you know your limitations, what are you going to do about it?

Contrast Training

Faster cycling is a fairly simple concept often over-complicated by riders and coaches alike in the quest for ever-more elaborate ways of improving performance. But cycling has, and always will be, about one basic premise: the more power you produce to propel the combined weight of you and your bicycle forward, the faster you will go.

You can throw all sorts of aerodynamic variables into the equation (there you go you see? Overcomplicating things already) but the bottom line is, faster riding equals improved power to weight ratio.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Every single cycling discipline in the history of the sport can be measured in terms of power, from the longest sportive where success depends on maintaining a relatively low wattage for hours on end to the shortest track sprints where massive power is needed very quickly for short durations.

So to go faster we need to produce more power without adding weight. In understanding this basic concept our next move should be to understand what power actually is (I think we all have a fairly good understanding of what weight is, after all).

You'll find all sorts of definitions of ‘power' ranging from other riders' opinions to coaches' views and internet forum gossip, but the best way to think of power is as a product of strength (how much force you can apply to the pedals) and speed (not MPH but the rate at which you can turn the pedals). So a perfect example would be two riders of similar weight pedalling at a cadence of 90rpm.

If rider (a) was able to apply greater force to the pedals, turning a 53x11 gear, that rider would go faster than rider (b) who is restricted to turning a 50x12 on a compact due to their inability to produce sufficient force on the pedals to turn anything harder.

So far so simple then, to improve we simply need to develop greater strength and faster leg speed. Speed and strength are two of the key components of fitness in many endurance sports and traditionally you'll find them occupying specific phases of any good periodised training programme.

The classical approach for road racers is to build strength in the gym over winter while working on high-cadence exercises that take care of the speed element. As the season approaches strength gains are converted to more cycling- specific aims with on-bike strength work and the introduction of targeted sessions to improve the other key component of fitness we've identified - power.

And this is where things start to get a little more complex, because in order to be a good sprinter, producing big watts or super-fast cadences aren't enough on their own, you have to be able to produce both simultaneously - not so simple.

In using the term ‘sprint power' here we're talking real top-end stuff that lasts for less than a minute - anything longer and you're moving into different territory, short-term muscular endurance, something quite different from all-out maximal sprints.

For sprints you need to produce the maximum amount of force you can generate (force developed in your strength sessions) in the quickest amount of time possible, and this relies on recruiting as many Type II muscle fibres as possible at the very instant that your brain tells your body to get busy - this is your neuromuscular efficiency, or how fast you can produce maximum power.

So given that we need to produce as much power as possible as quickly as possible, the most specific way to train for that would be to target both at the same time, as this is what would be required in a race situation, and this is where ‘contrast' or ‘complex' training as its often referred to comes in.

Sprinting in race situations demands speed and strength are used at the same instant, but how can we best train them together? The simple answer of course would be to try to replicate a race-sprint situation in a training session.

This is notoriously difficult to do as you rarely match the intensity of a race situation in training sprints and in doing so, riders understandably fatigue very quickly and nobody likes training at this kind of eyeballs- out intensity (witness some of the comments from our expert racers in sidebar one). This is where contrast training can help, as research shows it maximises speed and strength adaptations in the same session.

Track and field athletes have long used it to improve performance, but only in recent years has its appeal begun to branch out into a wide range of sports from endurance events to body building.

Contrast training relies largely on a physiological principle called Post Activation Potentiation (PAP), which means that the explosive capabilities of a group of muscles is greatly enhanced after they have been subjected to near maximal contractions.

In plain English this means you can produce more power, more quickly after subjecting the required group of muscles to some serious weight-lifting. At this point I hear you about to say, "Whoa, hold on a minute there, the only thing I get following near maximal weight training sessions is tired legs - how can I then perform with increased power?"

A not unreasonable question as fatigue is the most obvious effect of resistance training. But research shows that fatigue following resistance training coexists with PAP, and while the fatigue disappears quite quickly, PAP sticks around for up to 30minutes, allowing us the opportunity to maximise increased potential in the explosive exercises to follow.

Scientists studying the effects of PAP discovered that heavy loading of the muscles prior to explosive exercises induces a degree of increased central nervous system stimulation, resulting in greater motor unit recruitment and force than the tested athletes were capable of performing in standard sprint sessions*. In short, contrast training allows you to perform stronger and faster exercises - the two major factors in sprint performance.

How do I do it?

Given the above, you might think that taking a set of freeweights to a criterium and performing a few weighted squats in your warm-up prior to the gun going off is the way to go. Indeed legend has it that disgraced sprinter Ben Johnson did just that in the warm-up enclosure only minutes before his world record 100m at the Seoul Olympics in 1988.

But while there is sufficient evidence to support the fact that you could produce greater sprint power, too many variables co-exist within the race scenario itself that could possibly compromise this elevated power, tactics of the other rides being a perfect example.

Consequently, coaches have looked more closely at the chronic, long term effects of introducing contrast sessions into training to achieve sustainable improvements in sprint performance. The simplest approach is to modify the existing periodised plan to include contrast sessions.

So the ‘build' phase of the programme features weighted squats followed by plyometric exercises such as box jumps, then the more cycling specific contrast training is integrated in the pre-competition phase during the spring when racing is just around the corner.

What sort of intensity/recovery is involved? This is the key to successful contrast training. Clearly the amount of load you carry for the weighted squats influences greatly the PAP, as does the amount of recovery time before the explosive or sprint exercise is performed.

And like so many other areas of training, the effects are highly individualised based on the condition of the athlete in question (PAP seems to work better the more highly trained you become). So the thing to remember here is it's a simple case of suck it and see.

In the programme below we suggest a starting point for load based on the 1RM* system and you'll know how much time to leave between the strength and explosive components after just a couple of sessions' experience.

*RM stands for Repetition Max - or the maximum amount of weight you can use and perform one single squat - so use sufficient weight where 3 reps would take you to fatigue not failure.

Contrast training programme

16-weeks to improved sprint power

You'll need a barbell and weights, plus an 18in box or step for the introduction and build phase plus your bike on a turbo for the pre-competition phase

Introduction phase:

1-4weeks

Build phase: 1-6 weeks

3 sets of 3x80-90 per cent 1RM weighted squats

followed by box jumps*.

Be progressive in the box jumps; start with low

volume in week one (six or seven) and add one or two per set in each session. One session per week.

Pre-competition phase: 1-6 weeks

3 sets of 3x80-90 per cent 1RM weighted squats followed by one 15-second maximal sprint on the bike. 3-5 minutes recovery between each set.

Again, be progressive on the bike component - start using a moderately hard gear and increase the gearing gradually session by session. If you have a PowerTap you can monitor your progress quite closely, otherwise just go for it - these are after all maximum efforts. One session per week then one to two sessions per month for maintenance during race season.

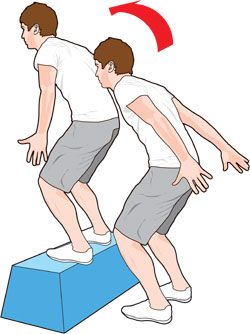

*Box Jumps

Stand with feet together on the floor a couple of inches away from an 18in box or step. Jump onto the box landing both feet together and land ‘soft' by bending the knees. Step forwards off the box, turn around to face the boxand repeat.

Simply include sets of weighted squats as part of your regular strength training programme, twice or three times per week.

This article was first published in the Spring 2011 issue of Cycling Fitness. You can also read our magazines on Zinio, download from the Apple store and also through Kindle Fire.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.

-

The National Cycling League appears to be fully dead

The National Cycling League appears to be fully deadEffective immediately, the NCL paused all its operations in order to focus on restructuring and rebuilding for the 2025 season.

By Anne-Marije Rook Published

-

Giro d'Italia 2025 route: white roads, twin time trials and a huge final week await in May

Giro d'Italia 2025 route: white roads, twin time trials and a huge final week await in MayThe three-day Albanian start could shape things early, too

By James Shrubsall Published