Should cyclists be worried about skin damage? All you need to know about protecting yourself from harmful rays

As high summer approaches, promising long hours of sun-drenched cycling, here’s what you need to know about the dangers posed by the sun and how to reduce the risk

This article was originally published in Cycling Weekly's print edition as part of the WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT series tackling taboos and raising awareness of cycling-related health issues.

"I’ve had dozens of surgeries in the last 10 years – and they’ve all come because of the amount of time I’ve spent outdoors.” Kimberley Conte had never thought much about the risk of skin cancer. “No one in my family had a history of it and I don’t burn easily, so I thought I would be immune from it. I didn’t take it seriously at all.” But then, in 2010, she was diagnosed with a very small basal cell carcinoma between her lip and her nose. At first, she had the affected area of skin frozen using a technique called cryotherapy, a proven means of destroying cancerous cells.

“‘No big deal’ was my attitude,” reflects the Australian, who is a race director of the Women’s Tour Down Under, “but what I couldn’t see was the cancer still growing under the scar tissue where it had been frozen, and it kept returning. Since then, I have had multiple surgeries, including graft surgery and a full reconstruction of the tissue between my nose and my upper lip, including a full tattoo on my upper lip [the latter for cosmetic reasons]. I just didn’t think something like this would happen to me.”

Today, Conte is well, but she lives in the knowledge that skin cancer can always return. At the beginning of the year, she had surgery on her lower leg to remove a squamous cell carcinoma after two previous attempts failed. “I felt like I’d just been through this six months ago, and here it was recurring,” sighs the 55-year-old. “I have had multiple other biopsies, surgeries and other forms of chemotherapy treatments to try to stay on top of the situation, including the removal of three melanomas on my back and arms. I’m grateful to the medical team who take care of me. It’s something that we all need to take seriously.”

Conte is right. Now that summer and the hot weather is here for us in the northern hemisphere, the days are long and we’re riding outside more than at any other time of the year, spending more time in the sun while it’s at its strongest. Riding outside gives many health benefits, but we need to be upfront about the risk of damage to our skin – even when it’s cloudy or not especially warm. Dr Derrick Phillips, a consultantdermatologist and British Skin Foundation spokesperson, puts it plainly: “The repeated exposure to UV rays from the sun while cycling can put you at increased risk of skin cancer.”

As with our previous features in this ‘Let’s Talk About’ series, the aim here is not to frighten cyclists, nor to cause you to cut down the amount of time you ride outside this summer. Our aim is simply to inform you of the dangers posed by the sun – and how to reduce the risk. None of us wants to go through what Conte and countless others have had to endure.

Sun protection basics

- Use sweat- and water-resistant sunscreen 30SPF+. Reapply every two hours.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

- Apply a skin moisturiser before the sunscreen, as it helps prevent the skin

cracking.

- Use summer cycling jerseys and bib shorts with a UPF30+.

- Apply sunscreen all over the body if not wearing garments with a UPF rating.

- Use a thin cycling cap under the helmet during the summer.

- Use sunglasses with UV protection.

- Avoid cycling between 11am and 3pm if possible.

- Check your body once a month for signs of skin damage, new marks or moles, or

changes to existing moles. Get a friend or partner to check your back.

Monitor your moles

It warrants spelling out: cycling, in itself, is not a risk to the health of your skin. Skin cancers are caused by DNA changes in skin cells, leading to uncontrolled growth of these cells. Excessive sun exposure can damage DNA in your skin cells, but it’s not the sole cause; other factors include genetics, skin type, hair colour and how many freckles and moles you have. Sun exposure is the factor we can control, so that’s what we’re focusing on here.

The two most common skin cancers are melanoma and non-melanoma. We’ll get into the details and differences between them shortly, but both share one common trait: people with fair skin, freckles and light or red hair are much more susceptible. Black people are not immune, but they have a much lower risk, as the pigment in their skin provides some protection.

Non-melanoma is much more prevalent and much less serious, as it’s less likely to spread to other parts of the body. Melanoma, so-called because it develops in the cells that produce the pigment melanin, is the most dangerous, as it can metastasise and become life-threatening. Early signs are new marks or blemishes on the skin, new moles or moles that change in size or shape. The advice is to check your skin at least once a month – ask a friend or partner to check your back, and return the favour – and if you notice a mark or mole growing, changing shape, developing new colours and/or measuring more than 6mm in diameter, you’re strongly advised to head to your doctor. Those with a family history of skin cancer or who have experienced severe sunburn in the past are at greater risk.

No one should underestimate or downplay the risk: Cancer Research UK says that 86% of skin cancer cases are preventable, and around 90% of all skin cancers are caused by overexposure to ultraviolet rays. One in 36 UK males, and one in 47 females, will be diagnosed with melanoma in their lifetime. Though the survival rate for melanoma is high, at 87%, the condition still kills around 2,300 people in the UK each year.

Develop awareness

Michael Cosgrove is a former mountain bike racer from Maryland, USA, who still rides between 150 and 200 miles a week, splitting his time between road, gravel and mountain biking. Last year he had a cancerous mole surgically removed from his shoulder – fortunately, the cancer had not spread. “I still feel relatively young, I’m in good shape, I eat healthy, do all the right things, and then all of a sudden I’m reading that melanoma can kill people,” says the 48-year-old. “That was kind of scary. I was sweating for a few weeks waiting on the results but in the end it was all good and I was happy; everything turned out OK because I caught it early enough.”

What most frightened Cosgrove was the location of the melanoma. “Although I always applied sunscreen, as I’m fairly pale, I never paid attention to my shoulders or my back. I only got them checked out because my mum had had some moles removed over the years, so I thought I should get twoor three on my back looked at.” Only when he visited a skin specialist was the problem picked up. “The moles on my back were OK, but it was the shoulder one – a mole that just looked like a freckle to me and hadn’t worried me – that was the cancerous one. It opened my eyes and I wish that every cyclist would see a dermatologist once a year because we’re all at risk.”

Cyclists spend a long time in the sun, so our risk is higher. In this century alone, two-time women’s world time trial champion Amber Neben and former Paris-Roubaix winner Magnus Backstedt have both had melanomas removed, while the late Spanish cyclist David Cañada underwent chemotherapy in 2008 after his melanoma returned as lymphoma; he recovered but tragically died in 2016, aged 41, after crashing during a sportive. Meanwhile, the 1987 Vuelta a España champion Luis Herrera overcame a nonmelanoma form of skin cancer in 2017 that he attributed to his years of riding. “If you don’t look after yourself, no one will look after you,” he commented.

Fortunately, there are easy steps we can all take to mitigate the risk, even if we can’t eliminate it entirely. If you can avoid riding in the sun between 11am and 3pm, do so, and it’s a good idea to wear a cycling cap under your helmet to protect the scalp, and wear sunglasses with UV protection to protect your eyes. The most important precaution, of course, is to use sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 30. Liberally cover all exposed skin before heading out, and ideally reapply every two hours, as heavy sweating can, over time, wash sunscreen off the skin. “Sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 blocks 97% of the sun’s UVB rays [the most harmful type],” says Dr Phillips.

What if the sun isn’t shining? “While your skin may not burn on a cloudy day, it still sustains damage,” Phillips explains. “UVB rays that cause burning are mostly blocked by clouds, but UVA rays can pass through, and these cause ageing.”

What do we need to know about the difference between UVA and UVB rays? “UVA rays have a longer wavelength than UVB rays and can pass through clouds and glass,” says Phillips. “Although they are less intense than UVB, UVA rays account for up to 95% of the UV radiation that reaches the earth’s surface. Due to its longer wavelength, UVA radiation penetrates to the deeper layers of the skin and affects the living cells beneath the skin’s top layers where wrinkles are formed.”

Back in 2014, Chris Froome posted a picture on social media of severe sunburn on his back that had penetrated his mesh base layer. It shocked many of his followers, but it was a timely reminder of the importance of applying sunscreen everywhere and also choosing cycling garments that have an ultraviolet protector factor rating of 30 or more. Most brands now average a rating of around 28, usually labelled on the garment’s tag.

Stay safe, stay riding

Effective precautions against sun damage are not burdensome. Sunscreen and protective gear take seconds to put on and do a good job of protecting us, with no notable downsides. Conte chimes in again with an important aesthetic observation.

“Us cyclists like our tan lines,” she acknowledges. “We like to look fit and healthy, and we’re at an advantage in that we know our bodies and we’re in a position to check our own skin. If you find an unusual spot or a new mole, it may just look like a tiny thing, but it could be melanoma.” This doesn’t mean you need to obsess. “Don’t get paranoid about it, but just be careful and get checked out. And if you’re not happy with what the doctor says, don’t be afraid to get a second expert opinion. The earlier we get a qualified person to take a look, the more positive the outcome is likely to be.”

Despite their sun-related scares and traumas, neither Conte and Cosgrove have curtailed their cycling. The former adds: “If you’re proactive you have very little to worry about – most problems are treatable if caught early. Although I am more careful and try to limit how often I’m exposed to the sun at its strongest here in Adelaide, I’m still enjoying riding my bike outside.” Cosgrove echoes the sentiment. “For sure, now I’ll be throwing sunscreen on everywhere, especially my shoulders and neck, and will be wearing garments that are UV-protective, but I’m riding as much as ever.”

Spotting the early signs of melanoma

Every rider should frequently check for signs of melanoma, especially those who have a lighter complexion and/or fair hair. Here’s what to keep an eye out for:

A for Asymmetry: one half of the mole/mark doesn’t match the other.

B for a Border that is irregular: the mole/mark has rough or ragged edges and the outline may look like it’s blurred into the surrounding skin.

C for Colour that is uneven: there may be shades of black, brown and also a tanned colour. It’s possible there will be areas of white, grey, red, pink or blue, too.

D for Diameter: most are larger than a pea, measuring at least six millimetres.

E for Evolving: the mole/mark changes over a period of weeks and months.

Many melanomas show all of the ABCDEs, while some only have a couple present. If you spot any of the above, get a doctor to check it out; if necessary, the mole/mark can be removed and/or checked for cancer cells.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

A freelance sports journalist and podcaster, you'll mostly find Chris's byline attached to news scoops, profile interviews and long reads across a variety of different publications. He has been writing regularly for Cycling Weekly since 2013. In 2024 he released a seven-part podcast documentary, Ghost in the Machine, about motor doping in cycling.

Previously a ski, hiking and cycling guide in the Canadian Rockies and Spanish Pyrenees, he almost certainly holds the record for the most number of interviews conducted from snowy mountains. He lives in Valencia, Spain.

-

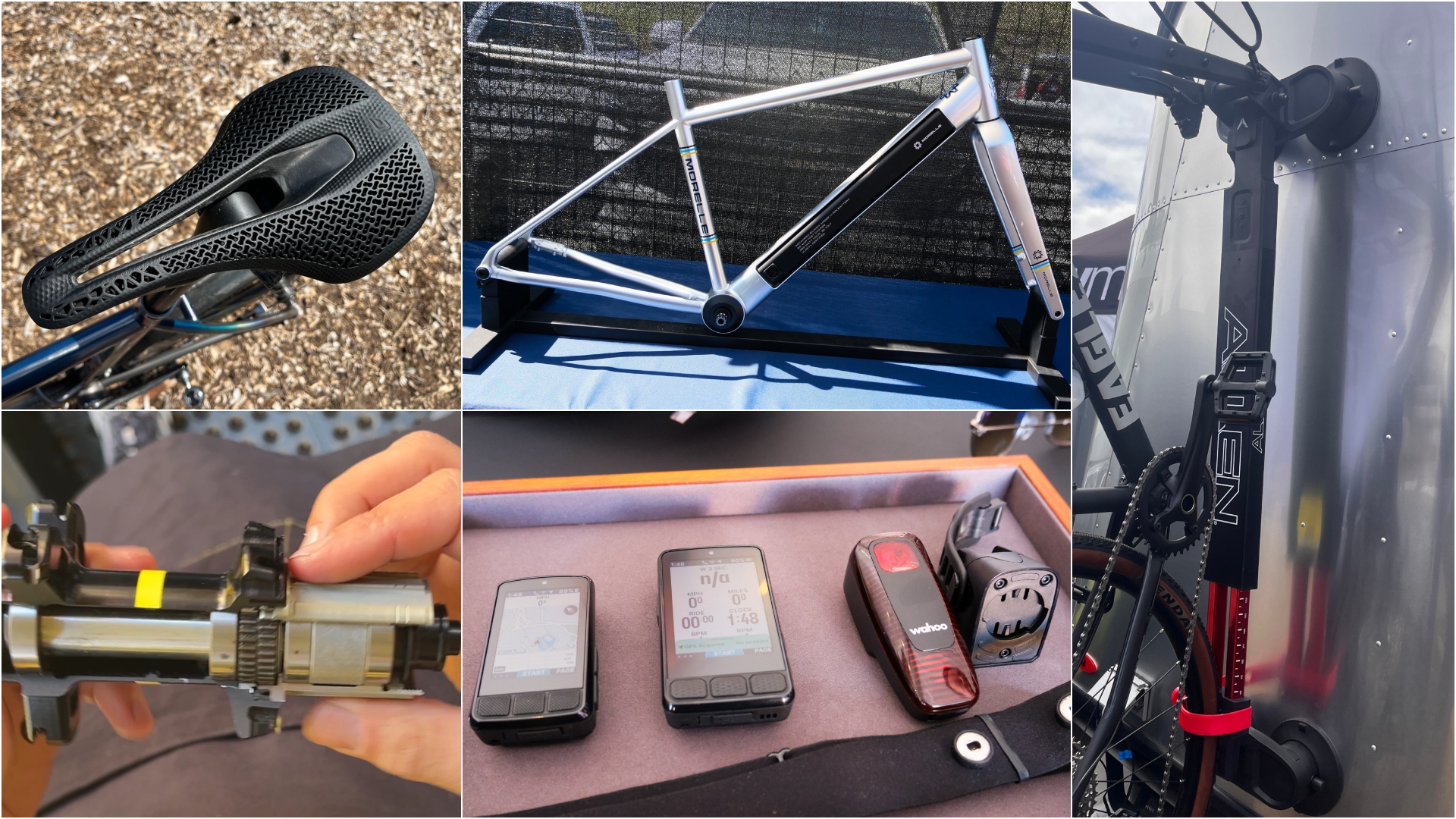

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2A few standout pieces of gear from North America's biggest bike gathering

By Anne-Marije Rook

-

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incident

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incidentCycling's authorities must do everything within their power to prevent spectators from assaulting riders

By Tom Thewlis

-

‘Even at 10mph you’re actually causing some noise trauma to your ears’: cycling and hearing loss

‘Even at 10mph you’re actually causing some noise trauma to your ears’: cycling and hearing lossStruggling to catch all the banter on group rides can be frustrating – but it shouldn’t be a source of shame or stigma. Chris Marshall-Bell calls for greater openness around hearing loss

By Chris Marshall-Bell

-

Cycling has a body image problem: what’s causing it and what you can do about it?

Cycling has a body image problem: what’s causing it and what you can do about it?Looking sleek, stylish and fast is an integral part of cycling, but brings with it a pressure to conform. Chris Marshall-Bell breaks the taboo on the sport’s body-image troubles

By Chris Marshall-Bell

-

‘Everything got a little bit better’: the role cycling can play in the grieving process

‘Everything got a little bit better’: the role cycling can play in the grieving processAt some point in our lives, every one of us will be affected by bereavement. we find out how cyclists can help one another through the grieving process

By Chris Marshall-Bell

-

Concussion is a feature in 90% of cycling head injuries - here’s what you need to know about the symptoms and recovery

Concussion is a feature in 90% of cycling head injuries - here’s what you need to know about the symptoms and recoveryOne of the most common cycling injuries, concussion is a warning sign that the brain has been subjected to potentially damaging g-force

By Josephine Perry

-

How to master your cycling-related nerves - from social anxiety on group rides to performance anxiety on race day

How to master your cycling-related nerves - from social anxiety on group rides to performance anxiety on race dayPre-race nerves are normal, possibly even helpful, but what if fears and unease begin to take the joy out of your cycling? We explore the troubling topic of anxiety

By Chris Marshall-Bell

-

Herpes, numbness, erectile dysfunction: Cyclists bare all on uncomfortable issues 'down there'

Herpes, numbness, erectile dysfunction: Cyclists bare all on uncomfortable issues 'down there'Long spells in the saddle can put our nether regions in jeopardy – but most of the risks can be prevented or at least managed. Chris Marshall-Bell tackles the taboo

By Chris Marshall-Bell

-

'Cycling eases the symptoms and gives me a strong sense of purpose': We need to talk about... Bipolar disorder

'Cycling eases the symptoms and gives me a strong sense of purpose': We need to talk about... Bipolar disorderIt’s one of the commonest long-term conditions yet it’s shrouded in stigma and misunderstanding. Chris Marshall-Bell meets two riders boldly speaking out about their experience

By Chris Marshall-Bell