Starting afresh: coming back to sport

‘You’re never too old’ so the goes the saying, and as more people are discovering, or returning to, cycling later in life, Helen Carter looks into the effects of making a sporting comeback

You're never to old...

As concerns for the health of the general population grow, it was hoped that the 2012 Olympics would “inspire a generation”. Such an event could boost physical activity and sporting participation, giving our country’s youth aspirations to become the next British heroes.

However, by the looks of people out riding on the road, the generation that appears to be most inspired are those in the 30-60 age group. Over 15 million people in the UK now participate regularly in sport (playing at least once per week).

But if you look at the statistics for sporting participation in the UK, there is a common pattern: most children of school age regularly play two or three sports, but once they reach university age (their late teens), the time they spend playing sport begins to reduce, but why?

Well there are a number of reasons. Entering work or going on to study at university means less time for hobbies, and as we’ve seen from responses to questions on our thread on the Cycling Weekly Facebook page, an interest in fast cars, partying and members of the opposite sex starts to be more appealing than the discipline of competitive sport!

And as we get older, the lull in physical activity coincides with a new way of life: establishing a career, taking on more financial responsibility, and starting a family.

However, by the time we reach our 30s and 40s, other motivations come in to play — our career may be on track, a level of financial security has (hopefully) been reached, and any children are old enough to be more independent of their parents. So, thoughts turn to leisure time once again.

People may also start thinking more about their health, too, around this age. It’s harder to stay at a given weight without upping exercise when you enter middle age — the aging process has started. While from a mental and emotional perspective, people begin to question what they want to do in their life, which means cycling can become a new project to focus on.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Sport also offers a way of creating a new network of friends and cycling offers a very sociable option. It is an activity that can be shared with others both on the road and at a coffee stop. Yet, it can cater for the individual too, with options such as time trialling and sportives giving autonomy to riders without sacrificing the social aspects.

Top tips

- Find age-relatedcompetitions and races totake part in and don’tunderestimate theimportance of rest and recovery

- Set yourselfchallenges and don’tcompare yourself withhow you usedto beTop tip

- Be clever in your riding and training. Experience cantrump youth

The wide variety of disciplines within cycling also opens up the possibility to focus on performance and to be competitive yet not in direct competition with others, setting a personal best, participating in challenge events, or entering races with age group classifications.

Endurance is one component of physical fitness that withstands the aging effect well, and so older athletes can still reach high levels of performance. This is especially the case with females. Those who take up, or return to, cycling in middle age, can still improve quickly and be reasonably competitive in the rankings. It is not uncommon to have amateur champions at national level in their late- 30s and mid-40s.

But you don’t have to be competitive to reap the health benefits of cycling. The sport is a great cardiovascular workout, yet it avoids the wear and tear on joints that weight bearing activities, such as running, bring.

Train smarter, not harder

Getting back into cycling can lead to frustrations though, and making a ‘comeback’ even if you cycled in your youth does present a few challenges.

Although you have the benefit of understanding the nuances of the sport and have knowledge of how your body responds in training, a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. For one, your head will be expecting you to be able to do things your body can’t. That hill that felt easy as a youngster when cycling regularly, can feel like a mountain when you start riding again.

Instead, old goals need to be relinquished and new expectations set. Sport has changed rapidly, and cycling is perhaps at the cutting edge of integrating sport science and new technology for high performance. For the returning cyclist, the familiar ways are often outdated.

One of the biggest challenges is aging. The physiology of a 20-year-old is very different to that of a 40-year-old. We need to consider what spare energy we have to train, the slower rates of recovery between sessions, and our potentially very different dietary requirements. Once upon a time our bodies may have been capable of playing sport every day; 20 years later four times per week might feel like enough.

Another factor is finding time to train. The middle-aged career-person may need to factor training around work. And finally, a return to sport also requires an element of ‘cracking’ the system. The language, the events and the fashions may have changed; it takes time to find one’s feet and get reorientated.

Getting back into it

Somehow, the human species appears hardwired to believe they can automatically reach former levels, or forget those passing years. The first step when getting back on the bike needs to be acceptance. But, while you may not be as young as you used to be, it is possible that performances during middle age can approach (or even surpass) those from young adulthood.

Be selective with where you pitch your goals and consider those events with age group targets and rankings, or forget other people and just work on bettering your own personal bests from where you are now — not where you used to be.

Older riders often report that although their bodies are less responsive to training and they need more recovery time, they train more effectively because they are more calm and calculated than they were in their youth.

Make use of all the great training information available and the numerous tools you can use to monitor your fitness, so that you can train more effectively. Often young riders over-train, race too much or try and be successful in too many different things. Veteran riders often have the advantage of wisdom, focus and experience.

The League of Veteran Racing Cyclists (www.lvrc.org) runs age-related road races and time trials. The League actively encourages older riders to get back into racing and will even allow you to race against older riders than your own age category if you are worried about your fitness. As you improve you will end up in the right category for you.

Participating in sport later in life can be incredibly rewarding: it provides an ultimate personal challenge, brings health benefits and allows us to meet new people. Key to this enjoyment is adjusting expectations set by past performances, or trying to mimic others around us. Ensure you start with a blank canvas and look to cover the basics. Ultimately, a slower build-up will lead to a higher pinnacle.

Cyclist stories

Reg rides again

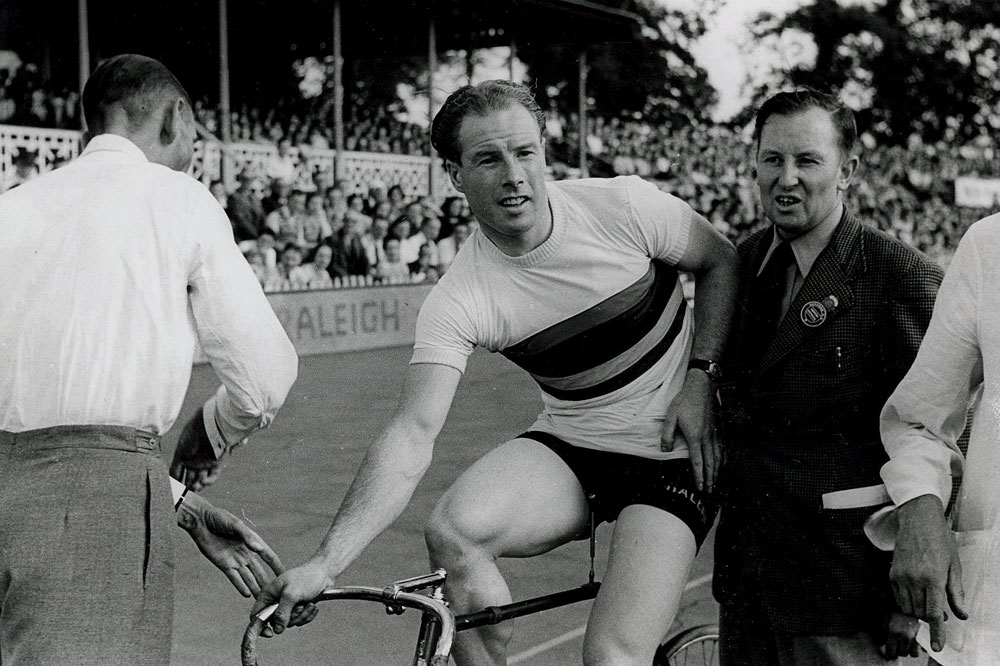

One of the highest profile pro rider comebacks was made by the five times world sprint champion (one amateur and four pro titles) and double Olympic silver medallist Reg Harris.

Harris was one of the first cyclists to become a household name in the UK, partly because of his achievements and also because of the advertising slogan associated with him, ‘Reg Rides a Raleigh’, seen on billboards and buses by people riding to work on their Raleigh bikes.

In 1957 after eight years as a pro rider, Harris stopped racing, and went into business. However, he never stopped riding. Harris started his cycling life as a touring cyclist and loved riding in the Cheshire lanes and with the local cycling clubs.

But Harris was fiercely competitive, and if anyone picked up the pace on a club run he’d be there, half a wheel in front. And if there was ever a sprint for a road sign, Harris was in it, elbows out and trying to win.

Eventually his competitiveness saw him apply for a professional racing licence in 1971. Back then, the sport was strictly divided into amateurs and pros, and Harris narrowly missed winning the national track sprint title that year. He was 51.

It whetted his appetite, and Harris went back into serious training. The same training he did in his heyday — hard road miles every morning. Then if there was time, training on Manchester’s outdoor Fallowfield track during the afternoon.

The training Harris did on the track is something sprinters today would still recognise. He warmed up, then did five flat-out sprints, sometimes against a motorbike, with 10 minutes’ recovery between each, so his ATP sprint power energy system could completely recharge.

With the correct training in place, Harris won the British professional sprint title in 1974, when he was 54, and returned the following year to take the silver medal.

Andy Stoneman

The moment Andy Stoneman knew things had to change came when he got an old suit out of the wardrobe for his grandmother’s funeral.

“I just couldn’t get into it. I felt like a fat blimp,” Stoneman said. “The next day I joined a gym and a few weeks after that I got a bike.”

Stoneman, now 40, had been a keen cyclist as a teenager: “I lived in a rough area of Leeds and the bike was my escape. I was doing 300 miles a week. I didn’t race or join a club, but I was extremely keen.”

He was also pretty fast, clocking up 24 minutes for a 10-mile blast from his home to the cycling hotbed of Otley. And he could go the distance — cycling from Leeds to Devon for a holiday.

But once Stoneman went to university and later started work, he lost interest in cycling, though not in two wheels: “I bought a motorbike and started my fish and chip diet.”

A poor diet and 14 years with no exercise took its toll and Stoneman ballooned from his youthful 76kg (12 stone) to 114kg (18 stone).

Then came his awakening. “I got a road bike. I went out and saw a hill in front of me and thought I’d struggle. But I got up it OK and I thought ‘It’s still in the legs’.”

At first Stoneman combined running and cycling, but now the bike is his weapon of choice. He’s back up to 250 miles a week, he’s down to 78kg and his waist has reduced from 42in at its peak to a svelte 32in. “I’ve rediscovered the joy of cycling and I love it. I’m hooked — again.”

Stoneman’s also the force behind a new club, Valley Striders CC, and his role motivates him to ride. While his other tips for getting back in the saddle after a lay-off, include: “Join Strava, it’s so motivating; get a bike you want to ride, because then you will; and set targets and enter events to keep the motivation high when it’s wet or windy.”

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.

-

How do the pros train? Noemi Rüegg's 26 hour training week

How do the pros train? Noemi Rüegg's 26 hour training weekWinner of this year’s Tour Down Under, the EF Education-Oatly rider is a climber whose talent is taking her to the top

By Chris Marshall-Bell

-

Save £42 on the same tyres that Mathieu Van de Poel won Paris-Roubaix on, this Easter weekend

Save £42 on the same tyres that Mathieu Van de Poel won Paris-Roubaix on, this Easter weekendDeals Its rare that Pirelli P-Zero Race TLR RS can be found on sale, and certainly not with a whopping 25% discount, grab a pair this weekend before they go...

By Matt Ischt-Barnard