Taking the plunge: How to nail your first race

Taking the plunge into racing is a landmark moment in the life of any competitive-minded rider. Rookie racer Charlie Graham-Dixon finds out what it takes to make the leap of faith pay off

After cycling on the road for eight years, starting out as a commuter on a single-speed bike before buying my first road bike four years ago, I finally took the plunge and started racing this March.

Why did I make the step up? Looking back, it’s clear that my competitiveness — comparing myself to other riders — predated any specific racing urge. Even as a commuter, I couldn’t resist sprinting away from traffic lights or beating fellow riders up false flats on the way to work.

>>> 11 things not to do at your first crit race

The competitive fires were stoked as I vowed to improve, ride more, and win that town sign sprint or local climb.

Why race?

Prior to racing, most road riders fall into the loose category of ‘leisure and fitness’ riders — cycling hard but just for fun, taking part in occasional group rides and sportives. They might watch the pros on TV and daydream about racing but without thinking they will ever themselves compete.

For my part, I suspected there was a huge gulf between my ability and the level required to race. Racing simply wasn’t on my agenda — yet.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In hindsight, I can see now that my ‘friendly competition’ among friends was also my first taste of racing. Like many riders, I saw that sustained, regular training and a steady improvement in performance gave me the confidence to test myself against like-minded other riders. There was finally no reason not to take the plunge.

Having made the decision, I followed a path familiar to many new racers in the UK — the rough and tumble of the British criterium scene. Criteriums (AKA crits), which last between 40 minutes and one hour, are ridden hard and extremely fast, usually climaxing with a bunch sprint. I hadn’t calculated precisely what would be required; I just went for it. Of course, you can be more scientific in your planning, it just depends on what you’re aiming to get from your first race.

How to prepare?

Every rider has their own level of fitness, resilience and strength, so there is no hard and fast rule to decide when someone has reached their optimum condition and state of preparation for making their race debut. In fact, many riders overthink their preparation. If you are fit, ride regularly and can handle your bike, here is a case for simply entering a race and ‘learning on the job’.

Coach Pav Bryan of Direct Power Coaching offers a useful rule of thumb: “The main thing to think about when first starting to race is whether you are competing or completing,” Bryan explained.

“If it’s the latter, you could simply rock up, after ensuring you are technically competent, and have a go. If you want to be competitive you’ll need to have been a bit smarter with your training. A good solid winter will set you up nicely for spring/summer races.”

Whether eight or 48 years old, riders entering their first race all start at the bottom of the ladder. In my case, as for the majority of new UK racers, this means Cat 4 crits or Cat 3/4 road races.

Race categories start at four, rising to one and Elite. How well a rider performs determines whether they rise up the categories, making it unlikely a new racer will compete in a field too far beyond their physical capabilities.

Regular riding and a good base fitness level should ensure sufficient fitness to at least stay with the bunch. Of course, a vital aspect of safe and successful racing is the skill and confidence to ride comfortably in a group. It’s important to practise riding in formation with friends in training, before taking to a start line.

“Don’t be that Cat 4 person who takes down the entire field by doing something reckless,” warns Bryan.

“Spend time learning the skills. Ride in groups, join fast group rides like chaingangs, watch some races, train your tactical and technical knowledge. This might take weeks or months, but is essential to get right before entering. If you get dropped in your first race, that’s OK, you can come back. If you do something irresponsible, you could really hurt someone.”

Once a rider builds experience from regular racing, they can fully focus on achieving good results — top-10 finishes and precious British Cycling points.

This is clearly something of a Catch-22, as for riders to gain racing experience, they need to take part in races before they have accrued the experience to perform well. Hence, it pays to keep your expectations low for at least your first few races, treating each one as a learning experience and a chance to develop key skills and get a feel for riding in a fast-moving bunch.

What kind of training?

Prior to racing, my training consisted of a mix of longer endurance rides on the road and short, sharp interval sessions, usually on the turbo trainer and ideally suited to the intense environment of crits. As my race approached, I focused more on shorter and more intense interval sessions, something Bryan recommends.

“If you’re preparing for crits, one-hour interval sessions are all you really need to do. Crits have hard starts, lots of breaks and almost always end with a sprint finish. You’ll want to train your body’s ability to recover quickly by doing high-intensity intervals with minimal recovery between.”

"Given criteriums often take place on technical circuits, changes in pace are common as riders slow for sharp corners and accelerate hard out of them. Crits involve a number of surges in power, therefore learning to feel comfortable at a high intensity is vital”

“You’ll need to apply a lot of power quickly, for breaking away or bridging gaps,” Bryan explains.

“These could be intervals at a very high intensity. Finally, you need to work on sprint power: what matters is firstly your peak power, and secondly how long you can sustain it for. Sprint intervals are the best for this.”

Leading up to my first race, I followed a specific weekly training schedule inspired partly by the circuit racing training plan used by British Cycling, combined with advice from friends and racers.

The plan consisted of indoor interval sessions of between 40 and 80 minutes two or three times a week and longer endurance rides of between two and five hours on the road once or twice each week. I also took part in local chaingangs whenever possible.

A key indoor session for race preparation, one I used regularly, was 20/40s — a brutal but highly effective workout most racers, whether on the track or on the road, know well.

The session involves close to maximum effort 20-second bursts followed by 40 seconds at around threshold, five times over, non-stop. After each painful set of five 20/40s, there is a four-minute recovery block before the intervals begin again. There is little respite and the body becomes more comfortable riding at high intensity, recreating the demands of races, and helping to increase VO2 max and anaerobic strength.

I found that while no training ever truly replicates the intensity of a race, fast group rides, in particular chaingangs, provide excellent preparation for the fast, ‘on the limit’ nature of a criterium.

Chaingangs teach riders how to ride close to their maximum while retaining concentration and learning valuable group skills, discipline and organisation. By following the ‘through and off’ technique, riders learn to draft, conserve energy and go faster as a group. Fast club runs and chaingangs also provide a valuable lesson in bike handling.

How to overcome fears and manage expectations

As my first race approached, I became increasingly nervous, worrying about crashing, causing others to crash, being out of my depth and getting dropped.

It was reassuring to learn that even pros go through this stage en route to the top. Olympic team pursuit gold medallist Jo Rowsell-Shand remembers how her first taste of competitive action did not go exactly to plan:

“It was a BMX race when I was 15. I couldn’t do the jumps or even ride over them normally! I came last in all three heats and by the final I thought it couldn’t get any worse.

“In the final, there was a big crash involving nearly every rider. As they untangled themselves on the floor, I rode past them and thought ‘Oh wow, I’m not going to come last this time!’ Unfortunately I was so slow everyone still managed to get on their bikes and passed me before the finish... I haven’t done another BMX race since!”

Rowsell-Shand story proves that it can happen to the best of us and that we are all human. Nerves and fear are normal emotions, and there are steps riders can take to ensure they reach the start of their race as relaxed as possible.

“Try and travel with a club-mate or team-mate so they can help you out,” Rowsell-Shand recommends. “Arrive early so you aren’t rushing trying to find where to go. An easy checklist ensures you have everything : start from your head and work your way down — helmet, glasses, jersey etc. And finally enjoy it and relax!”

As I pinned my number on for my first race, I looked at my competitors with their carbon machines, deep-section wheels and calves seemingly chiseled from granite. I felt nervous, but reminded myself that winning my first race was not everything; more important was learning racecraft and enjoying the experience.

Why it’s worth the pain

Racing is difficult in the short term but the subsequent endorphin rush and sense of achievement provides an unparallelled payoff. When I crossed the finish line for the first time, I was truly elated.

For any rider thinking of racing: there is no perfect time to start — you will never be 100 per cent ideally prepared — so enter a race now.

Yes, lots of training, fitness and group riding experience helps, but nothing can fully prepare you for the intensity and excitement of your first race. Some of the best training riders do is in races as the body acclimatises to the intensity required. Inevitably it’s nerve-wracking, but nerves are normal — they help ensure you give your best.

Though it’s easier said than done, enjoy the experience and savour the thrill. No rider wants to be dropped or crash, but the feeling after crossing the line is something every rider should experience.

Licence to thrill: Race licences explained

To take part in British Cycling road and circuit races usually requires a full racing licence. Prior to racing, I held a Bronze-level British Cycling membership, which gave me a provisional licence, but to race I needed to upgrade my membership to Silver then purchase the full licence. The cost of a senior (18+) annual Silver membership is £44 or £39 when paid via direct debit. The cost of the full licence is £36.

Having a full licence also means riders can obtain British Cycling ranking points should they finish in the top 10 of their race. From Youth/Junior up to Regional A races, day licences can be purchased by non-British Cycling members and discounted day licences are available for provisional licence holders.dd

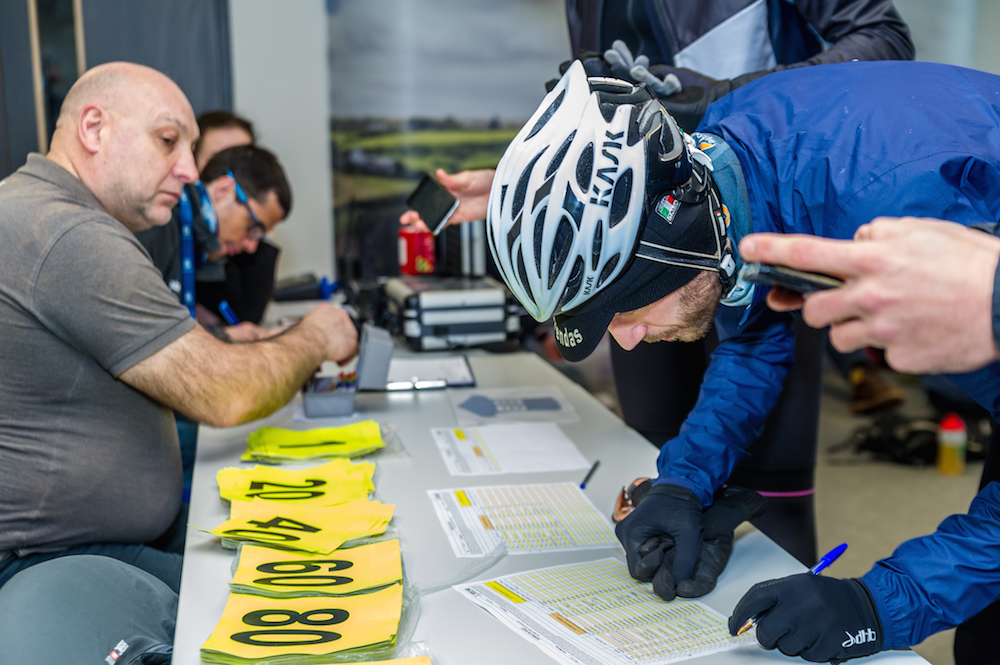

When signing-on at races, riders hand their licences to commissaires who provide rider numbers and transponders to attach to the front fork of your bike.

My first race: How it went and what it taught me

The race began with a sighting lap, which I began late after a commissaire ordered me to remove a rear light attached to my seatpost, which I had forgotten to take off. Not a great start. After rejoining the bunch and burning a match or two in the process, racing started in earnest and the pace was incredibly high from the start. Despite all the advice saying how vital positioning at the front was to conserve energy and avoid crashes, I felt uncomfortable moving up so early, preferring to get a feel for the bunch and hang on.

No doubt owing to some nervy cornering, I was sprinting out of most corners to rejoin the peloton — but I wasn’t the only one, and gradually found myself moving up. The cycling cliche that the bunch is a moving, living thing is no exaggeration; I was moving up and down it the entire race. One second I was at the back on my limit, worried I would be dropped, the next I was on the outside hurtling towards the front.

I even attacked off the front on a long straight and created a gap. Predictably, it was short-lived, as without the shelter of 40 other riders, I couldn’t hold the effort and was swallowed up.

Though this attack had been short and tactically naive, it gave me confidence. Had I been more comfortable riding in the middle of the bunch, I would have spent more time at the front, giving myself a better chance of a strong finishing position and using less energy.

In the end my first race went as well as I could have hoped: I finished in the bunch. With no breakaway sticking, the race was decided by a bunch sprint. I stayed upright and did not cause a crash, although there were some sketchy moments when other riders veered off line — easily done, of course, particularly for novice racers. Try to be consistent with your line and don’t make any sudden or unpredictable movements.

As I write this, I have recently completed my second race. Unlike the first one, I did a proper warm-up and, looking at my heart rate data, I spent most of the race in Zone 4 rather than at my limit in Zone 5. I was feeling more relaxed, had gained fitness and it was no longer bone-chillingly cold; it definitely felt easier.

I did my now customary solo attack, this time for a lap or so before I was caught by the bunch. I felt more confident and finished happy, albeit slightly disappointed that I was not positioned near the front for the finale and did not take home any British Cycling points.

My legs felt good and I learned a valuable lesson about crit racing — positioning and tactics are key.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Follow on Twitter: @richwindy

Richard is digital editor of Cycling Weekly. Joining the team in 2013, Richard became editor of the website in 2014 and coordinates site content and strategy, leading the news team in coverage of the world's biggest races and working with the tech editor to deliver comprehensive buying guides, reviews, and the latest product news.

An occasional racer, Richard spends most of his time preparing for long-distance touring rides these days, or getting out to the Surrey Hills on the weekend on his Specialized Tarmac SL6 (with an obligatory pub stop of course).

-

'I'll take a top 10, that's alright in the end' - Fred Wright finishes best of British at Paris-Roubaix

'I'll take a top 10, that's alright in the end' - Fred Wright finishes best of British at Paris-RoubaixBahrain-Victorious rider came back from a mechanical on the Arenberg to place ninth

By Adam Becket Published

-

'This is the furthest ride I've actually ever done' - Matthew Brennan lights up Paris-Roubaix at 19 years old

'This is the furthest ride I've actually ever done' - Matthew Brennan lights up Paris-Roubaix at 19 years oldThe day's youngest rider reflects on 'killer' Monument debut

By Tom Davidson Published