Training through the ages

For as long as there's been athletic competition, there have been training methods. And there's been cheating and doping too, but that's another dose of strychnine for another day.

What we're interested in here is the way bike training has changed over the decades; from Italian legend Fausto Coppi's famous dictum, ‘Ride the bike.

Ride the bike. Ride the bike!' to the use of the latest sophisticated training aids like the SRM power meter and its strain-gauge loaded power-measuring variants. The technology has clearly changed, but what about the training methods?

It's easy to get carried away with the latest gadgets and bolt-ons for our bikes and bodies, but is it possible that, underneath the veneer of technology, the essentials of training to cope with cycling are the same as they ever were? Bikes have improved, technology has changed enormously, but your cardiovascular system is the same as it's been for millions of years.

In the early days of cycle sport - when stages in the Tour de France could be 300km long and dope controls simply didn't exist - the bedrock of every serious bike riders training regime was ‘getting the miles in,' a phrase which has echoed down the years and can still be heard in club rooms, muttered by desiccated men who think carrying a bidon of water on a ride of less than 90 miles is a sign of weakness.

This notion, like many others in early cycling training orthodoxy, was imported from athletics, whose early coaching theory and practices were more organised.

To be fair though, those runners, jumpers and throwers had had a bit of a head start on cyclists - a couple of thousand years in fact - since Pheidippides jogged between Marathon and Athens with his war report. Actually, not only did Pheidippides ‘invent' the marathon, he also demonstrated the perils of overdoing it, dropping dead of exhaustion on arrival.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Strong foundations

Concepts such as ‘foundation miles' and ‘base miles' were common enough in athletics coaching circles and there was an obvious crossover between athletics and cycling. Distance running was a fundamentally aerobic activity that required a highly efficient cardiovascular system.

So, add a little bit of interval training to help with those moments of acceleration and attack - imported from middle distance running coaching manuals - and fartlek sessions to keep rider and athlete fresh and that, in a nutshell, was the basis for most cycle coaching for decades.

And of course, we can't forget the other foundation of much coaching ‘method' - pure acts of faith. Until the 1960s it could be argued that coaching and training wasn't so much a science as an art.

However, by the early 1970s, enterprising British coaches were building their own ergometers, manually measuring heart rates and calculating power outputs, putting riders through controlled interval training sessions on these early turbo trainers.

There were was no easy ECG-accurate measurement of heart rates, no gas analysis or pin-prick blood samples measuring lactate thresholds back then of course, but you can see that the principles of modern training methods were already taking shape.

In the end, sports science caught up with Fausto Coppi. Recall Coppi's 1940s insistence that in order to ride well you needed to ‘Pedalare! Pedalare! Pedalare!'? Well, it turned out that Fausto was talking about was ‘the specificity of training effect'. If you wanted to be good at a sport, if you wanted to be fit for a sport, you need to replicate the demands of that sport in your training.

Fausto Coppi believed that high mileage was key

Around the same time, in the late 1970s, as the health and the fitness (the ‘aerobics explosion') of their populations became more of an issue for Western governments, resources for sports physiology departments were ramped up - not forgetting the Eastern Bloc's state funding of sport.

The net outcome was a significant increase in credible research which gradually found its way into coaching practice. Little by little, sports science departments started appearing in universities, even if the set texts for those early courses were limited in number and invariably Scandinavian in origin.

It's ironic though, given the early reliance on athletics training methods, that sports science lab research was often based on the cycling ergometer, as British Cycling coach educator Professor Richard Davidson explains: ÏIt was a lot easier to measure someone on a static bike than it was on a treadmill.

Someone sitting on a bike is easier to stick a needle into than a runner bouncing on a treadmill! It still is.

What Davidson does confirm though is that there was a real paucity of quality research from which to develop cycling training from. ÏWhen I did my degree in the late 1980s the set text was still - and only - Astrand and Rodahl (Textbook of Work Physiology) and the Association of British Cycling Coaching (ABCC) manual at the time was pretty basic - as was the athletics coaching equivalent.

There really wasn't a lot of information out there. That was in the days before the internet hooked up the world and sports science departments everywhere.

But, if cycling had originally looked to athletics for training ideas, the arrival of lightweight wireless heart rate monitors and the concept of heart rate training zones in the mid to late 1980s was more quickly adopted by the cycling fraternity.

Knowledge is power?

When you look at what is available now - in terms of enabling technology like heart rate monitors and power meters, as well as information - we've gone from knowledge deprivation in the 1980s to knowledge overload today.

If you look on any forum that's talking about power output, the detail is overwhelming, there's too much information being looked at in too much detail. Even amateur cyclists have more information and testing devices at their finger tips than sports scientists in universities had 20 years ago.

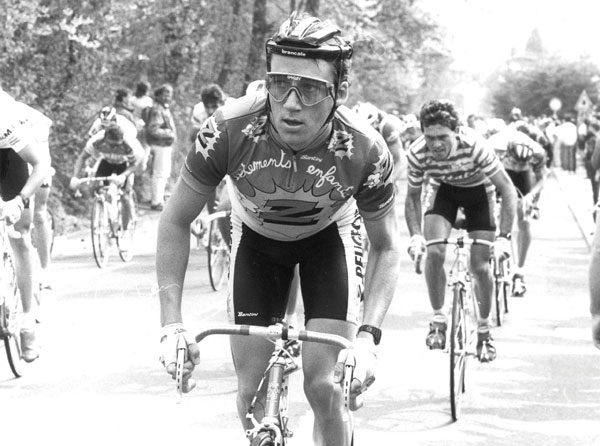

There is nobody in the UK better placed to appreciate the changes that have taken place in training than Adrian Timmis.

Pro time trialling: without mod cons, you'll lose

From junior pursuit champion, 1984 GB Olympic team pursuit member, road pro with ANC and Z-Peugeot, Tour de France rider transformed into World Cup XC mountain bike rider, turned soigneur and coach at Cadence Sport, it's fair to say that Timmis has been both eyewitness and guinea pig in every sense.

Timmis agrees with Davidson's picture of the information overload. The various power meters available now have changed training and coaching more than anything else that's happened since I've been riding, he insists, Ïbut there are people who fit power cranks because they just want to look at the numbers, which is kind of pointless.

The vast majority of people need help to understand what they are looking at and how to use the data they've got in front of them.

Which is a long, long way from doing weight training above a cow shed with his early mentor Paul Swinnerton when he was 17 and junior pursuit champion.

Timmis had (and has) a famously smooth pedalling action and understands now why that was a useful bedrock to his career. ÏWe can use power meters and ergometers now to measure pedalling efficiency, whereas all we knew when I was a junior was that if you didn't have a smooth pedalling style, you couldn't pedal a fixed wheel bike on track and you'd bounce up and down on the saddle.

But at a time when the British Cycling Federation was under-funded and essentially run by well-meaning, unpaid volunteers (basically anyone who put their hand up could get a job, regardless of skill level), coaching was unrecognisable from what it is today.

I can't really remember getting any specific training programmes for the pursuit before the Los Angeles games in 1984, we were left to our own devices really. The squad rarely got together, there was no indoor track and I reckon I was tested in a lab twice or three times in the run up to the LA Olympics.

It was buying a first generation Polar Sport Tester heart rate monitor and a young physiologist attached to the pursuit squad which helped Timmis understand what was going on and what he needed to do. ÏEven before we rode the Tour with ANC-Halfords in 1987, there was no training, no coach, no programme and it wasn't any different at the Z-Peugeot team either.

I had been to see Peter Keen with the pursuit squad and worked out my heart rate training zones with him - but that was typical, really - you were left to make your own way.

Now that there's a plethora of information everywhere, you would imagine that coaches are seen as an essential tool to help riders interpret all this data. The presence of club coaches in athletics was well established and in the past 20 years the coach has become a more accepted part of the cycling landscape. In addition, the tools - both in terms of hardware and a data and communications has put the UK near the forefront of cycle coaching theory and practice.

Coaches are now training riders with a far better understanding of what each event requires from riders' bodies. It's mostly still about ‘riding the bike' but now we're doing it in more measured, specific ways.

And the future? Genomics. Yes, forget measuring watts and examining basic blood chemistry, in the near future coaches will be taking DNA samples to check whether or not particular combinations of genes are present and active. ÏIt's not so much checking to see if someone has the potential to be good, to see how well they will respond to a particular training load, it will also help to work out what you should and shouldn't be doing in training to get the best out of your body,Ó notes Davidson. Truly, in some ways we've come a long way since Coppi.

Modern devices measure power using strain gauges

Training trends and fads

Throughout history, trends in training have come and gone. Some, however, have just had a makeover and new name. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, the fundamentals are spot-on. The big changes that have taken place are in our understanding of what we are training our bodies to do with technologies helping to take a lot of the guesswork out of our training programmes.

Getting the miles in An Anglo equivalent of Coppi's dictum. For some riders, this was the beginning, middle and end of their training, winter to summer and back again. The more miles you rode, the better you would get. End of.

Modern training theory still appreciates the importance of an ‘endurance base' of low intensity and long duration riding. What we know now is that such rides strengthen tendons and train muscle fibres to be more efficient and economical. But riding endless miles at moderate pace is just the, er, base.

Fartlek Imported from Swedish athletic coaches who wanted to give their runners a break from endless track-based sessions, the word was translated as ‘speed play' and allowed runners to jog, sprint and run through the pine forests as they pleased. Cyclists were allowed to ‘structure' one road ride a week in the same way. Unstructured it may be, but those random supra-maximal hill efforts and road sprints we now understand as helping us cope with lactate production and tolerance. But with added fun!

Interval training Here was another ‘innovation' in training that was popularised among middle distance runners and transferred to cycling coaching. While most riders were happy to ‘get the miles in,' the more sophisticated added ‘interval training' of wildly different durations, repetitions and intensities.

Devices provide real-time wattage data

Now we use heart rate monitors and measure watts to quantify the quality of the various intervals we do. Hill reps? Lactate production sessions? Lactate tolerance training? We're no longer sprinting between roundabouts or trying to hold 26mph on bar-mounted speedos. Interval training has existed for decades and now we can measure the effort and effect more accurately to reflect precisely what we are training our bodies to cope with.

Scientific training As Polar heart rate monitors became more portable and marginally more affordable in the late 1980s and early 1990s, some riders spent £300 on a Polar Sport Tester that would actually record an hour of data with samples of heart rate taken every five(!) seconds. ‘Scientific training' was the buzz phrase of the era.

Suddenly the bike speedo on your handlebars was replaced by a heart rate monitor the size of a portable black and white telly.

Overnight, riders were able to fine-tune their training in ways that were unavailable a decade earlier. The concept of heart rate training zones that could be measured in real time on training rides is still the bedrock of the work that many riders and coaches study.

SRM power meter Around 1991, at the same time as amateur riders were grappling with concepts like lactate threshold and working out which numbers they wanted to see on their heart rate monitors, the European based pros - notably Greg LeMond - started fitting early, SRM power meters, to the disgust of their mechanics.

The German developed SRM device was even bigger and heavier than those earlier Sport Testers, but could record a lot more data and a lot more interesting data. Heart rates were out, real time power output was in. Never mind the beats, feel the watts.

Although the SRM power meter is still expensive, there are slightly cheaper variants (the PowerTap hub) and the latest, the Look/Polar Keo pedals with built-in strain gauges means measuring power output is now available for the wealthier amateur. The joy of watts is that they aren't affected by fatigue or ambient temperature. You either make the power or you don't, not like that pesky, unreliable heart.

The problem with these devices is the amount and detail of the data generated. If you are willing and able to invest in this sort of technology then investing in a coach to help with the interpretation and structure of your training is a no-brainer.

High intensity interval training A modern variant of old school interval training, it's the equivalent of a miracle diet, in as much as it seems to promise a lot in return for relatively little (time). Essentially a series of short, ultra high intensity repetitions, a whole session might take 20 minutes. Imagine! From fat to fast with an hour's training a week. The reality is, surprise surprise, a lot more nuanced.

Timmis's tips - ask an export

Given Adrian Timmis's wealth of experience as rider, physio and coach, it would be remiss of us not to offer some of Adrian's basic training tips.

If you're serious and invested in a Power measuring device of some kind, get a proper coach to help you understand what you are looking at. I know hindsight is great, but it's certainly one of the things I would have changed. Even if you feel confident about the physiology, having someone who understands that side of things and who can give you another opinion or ideas is useful.

It's the recovery than makes you better, not the training. The great thing about being a full time bike rider isn't that you've got more time to train, it's that you've got more time to recover.

Get your nutrition right: ÏThis is another area I wish I had known more about when I was a pro rider. It's not just what you eat, it's when you eat. Even getting the basics right can be a help.

Work out what you need to do to improve: If you blow up on hills, it doesn't necessarily mean you need to do more hill work. If you race a criterium and your heart rate averages 190, that doesn't mean you have to train at 190bpm - you'll probably find you need to work on generating more power in your short sprinting efforts because you sprint out of corners a lot and that's the big effort.

Learn to pedal properly: I see too many riders who treat their bikes as a sort of mobile leg press, just mashing down on the pedals. Pedalling in circles is important and there are drills that can improve and train that till it becomes automatic.

This article was previously published in Cycling Weekly magazine. You can also read our magazines on Zinio and download from the Apple store.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

-

Save £42 on the same tyres that Mathieu Van de Poel won Paris-Roubaix on, this Easter weekend

Save £42 on the same tyres that Mathieu Van de Poel won Paris-Roubaix on, this Easter weekendDeals Its rare that Pirelli P-Zero Race TLR RS can be found on sale, and certainly not with a whopping 25% discount, grab a pair this weekend before they go...

By Matt Ischt-Barnard

-

"Like a second skin” - the WYN Republic CdA triathlon suit reviewed

"Like a second skin” - the WYN Republic CdA triathlon suit reviewed$700 is a substantial investment in a Tri Suit, and it is, but you’ll definitely feel fast in it

By Kristin Jenny