FTP or Critical Power – which is the best cycling fitness test?

Is it time to ditch the traditional FTP test in favour of the more scientifically advanced Critical Power? Coach Tom Bell puts theory into practice on two unwitting CW staffers

If you’re even remotely interested in cycling performance – or a user of the best indoor cycling apps such as Zwift – you’ll be familiar with the concept of ‘functional threshold power’ or FTP. Theoretically, it is the maximum power that can be sustained for 60 minutes, and is a marker of general aerobic fitness. It’s useful because it helps define cycling training intensity zones and calculate metrics such as ‘training stress score’ (TSS). The more scientifically sophisticated rival to FTP is Critical Power (CP) – but is it really a superior cycling test and, if so, why?

Before getting down to business as to what test is better, you won't be able to crunch any data unless you have some equipment with which to capture the measurements. It's well worth clicking through to out best Black Friday bike deals hub to check out some of the impressive discounts and deals that brands have on offer for the sale period, saving your self a decent amount of money.

Critical Power, though similar to FTP, is finding favour among cyclists who place a premium on accuracy and in-depth data analysis. For the same reason, it is the preferred benchmark among sports scientists and national cycling federations including British Cycling. So should you too be testing CP instead of FTP? Let’s face it, no one enjoys cycling fitness tests, so you probably don’t want to perform more than one type. It’s time to choose.

We’re going to find out if CP offers advantages as a bike fitness test – both theoretically, in terms of the science, and practically in the real world – by sending CW staffers David Bradford and Dan Baines down to the Shed of Suffering to take the test. Our aim here is to establish whether, for ordinary riders, CP really is superior to FTP – and whether it should be your go-to cycling fitness test.

FTP vs CP: What’s the difference between these cycling fitness tests?

FTP is a performance-based measure of fitness. Quite simply, it’s the amount of power that can be produced over a single defined duration. Importantly, FTP tells you little about how well power can be produced over shorter or longer durations; it just gives a fairly basic snapshot of ‘fitness’ at any given time. While FTP is usually defined as 60-minute power, most people use abbreviated tests such as a 20-minute time trial or a ramp test to estimate their FTP. In practice, the FTP estimate generated by these abbreviated tests is, for most riders, sustainable for only around 40 minutes.

One of the key reasons that FTP has proven so useful as a fitness marker is that it tends to sit very close to the important physiological threshold where power output tips from being ‘sustainable’ to ‘unsustainable’. Above this threshold, the aerobic system cannot keep up with the rate at which energy needs to be produced, and fatigue sets in quickly. Below this threshold, fatigue is more closely linked with glycogen depletion and fatigue of the central nervous system, which take hold more slowly, meaning power is sustainable for much longer. The crucial point is this: FTP is a fairly crude estimate of this important physiological threshold and, on an individual basis, it’s often quite inaccurate.

Critical Power determines the same ‘sustainability’ threshold but unlike FTP it is calculated based on how a person’s power drops off between shorter and longer durations. The CP model does this by plotting the relationship between an athlete’s power over different durations – at least two efforts are required – and thereby determines the individual’s unique rate of power drop-off. By analysing this relationship, we can then produce a better estimate of the physiological threshold where power output tips from ‘sustainable’ to ‘unsustainable’.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In practice, CP generally comes out slightly higher than FTP and is usually a power that’s sustainable for between 30 and 40 minutes. Like FTP, CP is a good marker of general aerobic fitness and is strongly linked with performance in a range of endurance disciplines.

What is W’ in cycling?

The biggest advantage of CP bike fitness testing is that it offers an extra parameter not provided by FTP: written as W’ and pronounced ‘W-Prime’ or ‘Work-Prime’. W’ is the amount of work that can be done – i.e. energy expended – above the CP before task failure. In endurance cyclists, this value is usually between nine and 25kJ for men, and between six and 18kJ for women – depending on fitness.

W’ is a really useful parameter, because it effectively tells you the size of your ‘anaerobic battery’. Let’s say two riders both have a 250W critical power; the one with the bigger W’ will be able to hold a 300W effort for longer and in a race will be able to repeat more surges above their CP. In this way, knowing your W’ can help you to understand your relative strengths and limiters, and it allows you to generate predictions for how much power you can hold in efforts above your critical power. It’s time for our CW guinea pigs to put CP to the test…

How do these cycling fitness tests work in practice?

Cycling Weekly’s mag Fitness Editor David Bradford writes: I’d never had a problem with FTP. It was easy to measure, provided a snapshot of my aerobic fitness and seemed a reasonable basis for my training zones. That said, my FTP was set too high on Zwift, as the platform automatically adjusts the figure based on race performances, and mine dated back to a halcyon spell on an outrageously generous smart-trainer (Zwift auto-adjusts only up, not down). To put this right prior to CP testing, I jumped into a CW Club 10 virtual TT and averaged 330W – giving me a more realistic FTP of 314W. But was this really the right number to guide my training, or was it too rudimentary an estimate of my sustainable power?

I’d heard many times from coaches and experts that CP offered greater precision, and I was intrigued to know whether mine would differ from my FTP. More importantly, what more could CP tell me about my bike fitness and how to train? Coach Tom Bell had explained that, to test my CP, I’d need to do at least two maximal efforts on the smart-trainer. He suggested one of three minutes and another of 12 minutes, each from fully rested, ideally on separate days. Which sounded simple enough…

What I hadn’t really thought through was just how hard a maximal three-minute test would be. It’s something I never do in the course of routine training, and let me tell you, dear reader, it hurt. A lot. The first minute was OK, and the second tolerable, but every second of the final 60 seconds was a lingering hell of frantic gasping as my heart rate galloped close to max. Finally making it to 3.00, I slumped in a drooling mess over the bars, my airways rasping and scorched – and I didn’t feel fully recovered until several hours later.

The next day, the 12-minute effort felt a little less brutal, being more like a familiar TT effort, but it still required an all-in level of commitment not to be taken lightly. Tom had warned me that I needed to get close to failure, otherwise my CP would not be accurate and I’d have to redo the test. There is no getting away from it: the twin maximal efforts are quite an ordeal and require considerably more willpower than an FTP test. Are they worth the pain? This would depend on the applicable insights that could be extrapolated from our results. CW art ed Dan Baines gamely agreed to follow the same protocol, to make our experiment more scientific – giving us two sets of data. These are the results we ended up with:

David

- FTP: 314W (4.6W/kg)

- 3min: 434W

- 12min: 356W

- CP: 330W (4.9W/kg)

- W’: 18.7kJ

Dan

- FTP: 342W (4.6W/kg)

- 3min: 478W

- 12min: 371W

- CP: 335W (4.5W/kg)

- W’: 25.7kJ

Interpreting the results

You’ll notice a few telling differences between my and Dan’s test results: the gap between my three-minute and 12-minute power is 78W, whereas Dan’s are worlds apart with a gap of 107W. Though I’m giving away only 15W to Dan over 12 minutes, in the shorter test he boots me into the weeds with a clunking 44W advantage. This accounts for the large difference between our W’: Dan has an industrial-sized ‘anaerobic battery’ of 25.7kJ whereas mine is a standard A A at 18.7kJ. Remember, W’ is the amount of energy each of us is able to expend above our CP before we hit our limit – Dan has much more in reserve.

“Dan’s high W’ marks him out as the punchier rider,” says Tom. “He’d be better-suited to shorter, more stochastic [unevenly paced] race formats, whereas you would be more suited to longer, more steady-state disciplines like longer time trials and sportives.” This comes as no surprise: Dan is a seasoned cyclo-cross racer, while my competitive background is in long distance running. The CP data allows us to set more realistic expectations in interval sessions too. “Your results suggest that in a five-minute all-out effort Dan would be able to hold 126% of his CP, whereas you’d be able to hold 119%,” says Tom. “This illustrates how knowing a rider’s W’ helps to adapt training intensity targets up or down.” Using an online CP calculator, such personalised training guidelines are at your fingertips – you don’t need to worry about the maths.

What Tom says next surprises me: Dan’s XL battery is not necessarily the enviable endowment I’d assumed. “Dan’s W’ is higher than we’d ideally like to see for an endurance cyclist, relative to his CP,” pronounced the coach. “Depending on his training goals, I’d probably recommend that he cuts down on the intensive training above FTP/ CP and spend more time riding at low intensities to bring his CP into better balance with his W’.” In contrast, my CP and W’ are beautifully balanced (OK, I’m paraphrasing!), meaning I’m free to follow a “rounded programme” that seeks to raise both benchmarks.

The part of our results that is troubling me most is that my CP is exactly the same as my 20-minute power. Had I gone through all that agony just to end up with the same number I’d already got in my FTP cycling fitness test? It evidently isn’t quite that straightforward, as Dan’s CP of 335W is 25W less than his 20-minute power. Tom’s advice to reset FTP at 96 per cent of CP means that mine goes up by a mere two watts to 316W, whereas Dan’s comes down by 20 watts to 322W. “Because Dan has a high W’, the more basic 20-minute FTP bike fitness test tends to overestimate his sustainable power,” explains Tom. “Your W’ is more ‘typical’ for an endurance cyclist, and therefore the FTP test works better – but we wouldn’t have known this without having done the CP cycling fitness test.”

This is a key point: the CP cycling fitness test has given us new information about our strengths and weaknesses by putting concrete numbers on characteristics we’d only sensed or guessed at. The data confirms that Dan is a punchy rider who excels in short bursts at high watts – this is useful information as he now knows he needs to do more long, low intensity rides. Conversely, I’m a single-paced diesel suited to long, sustained efforts, with plentiful room for improvement in my shorter-range ability. Will I continue to test CP? Honestly, probably not – there’s just not a big enough payoff from the pain of the multiple flat-out efforts, given I now know that, for me, the simpler FTP bike fitness test is quite accurate and not misleading. But don’t let my experience put you off, as the insights gained differ from one rider to the next. If you want to know what the CP cycling fitness test has to offer you, there is only one way to find out!

Cycling fitness tests for determining your CP

There are a few different ways to determine Critical Power. Tom Bell’s recommended approach is to perform at least two all-out efforts, with the first one being between three and five minutes, and the second being between 10 and 20 minutes. For even greater accuracy, you can do a third effort of between six and eight minutes.

For (relative) simplicity, use this method:

For the warm-up:

10min @ 50-65% FTP

2x 2min @ 105% FTP (2min recovery between)

10min @ 50-65% FTP

The test

Maximal 3min effort

Full recovery, ideally a whole day

Maximal 12min effort

Pace each effort so that your power is relatively stable from start to finish, getting close to your limit by the end. This isn’t easy, so use data from previous hard efforts to guide your power targets and pacing strategy. The first third should feel manageable, the second third tough, and the final third should feel like a 10/10 effort.

Take the average power you held for each of the efforts – in Strava Premium, click on the ‘analysis’ tab, highlight the effort, then it’ll display the average power – and plug these into a Critical Power calculator which will automatically generate your Critical Power and W’ values.

You’ll want to repeat the CP bike fitness test with the same frequency as you’d usually test your FTP, i.e. every eight to 12 weeks.

The W’ Potential: Tracking the battery life of the body

Performance consultant Alex Welburn is midway through a PhD at Loughborough University investigating the potential of Critical Power and W’

Though W’ is commonly referred to as the ‘anaerobic battery’, strictly speaking it’s not anaerobic, which means ‘without oxygen’. You’re still using oxygen even when you are working above Critical Power. In the severe intensity domain, many factors combine to cause fatigue to rise exponentially until task failure.

W’ represents a fixed amount of work that can be done above CP before failure is reached. It’s relatively easy to convert watts into work: if you’re doing 50W above CP, you’re using 50 joules per second – or 1kJ every 20 seconds. When you are below CP, your W’ recovers – like recharging a battery.

However, so far there is only a small body of work looking at both the use of W’ and its recovery. This is what we at Loughborough are trying to understand more with our research. It may allow us to narrate races in terms of W’ depletion and recovery, and create Individualised work- to-recovery ratios for interval training.

This is ultimately what our research is trying to ascertain – how to further individualise W’. It’s theoretically possible to develop an accurate pacing plan tailored to your own physiology.

Already there is an app called ‘W’ Balance’ on the GarminLabs platform, which uses CP data to show W’ in real-time on your head unit. The more work we do, the better we’ll understand how useful this form of monitoring can be.

This article was originally published in the print edition of Cycling Weekly. Subscribe online and get the magazine delivered direct to your door every week.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Tom Bell is reigning British hill-climb champion and coach at High North Performance.

-

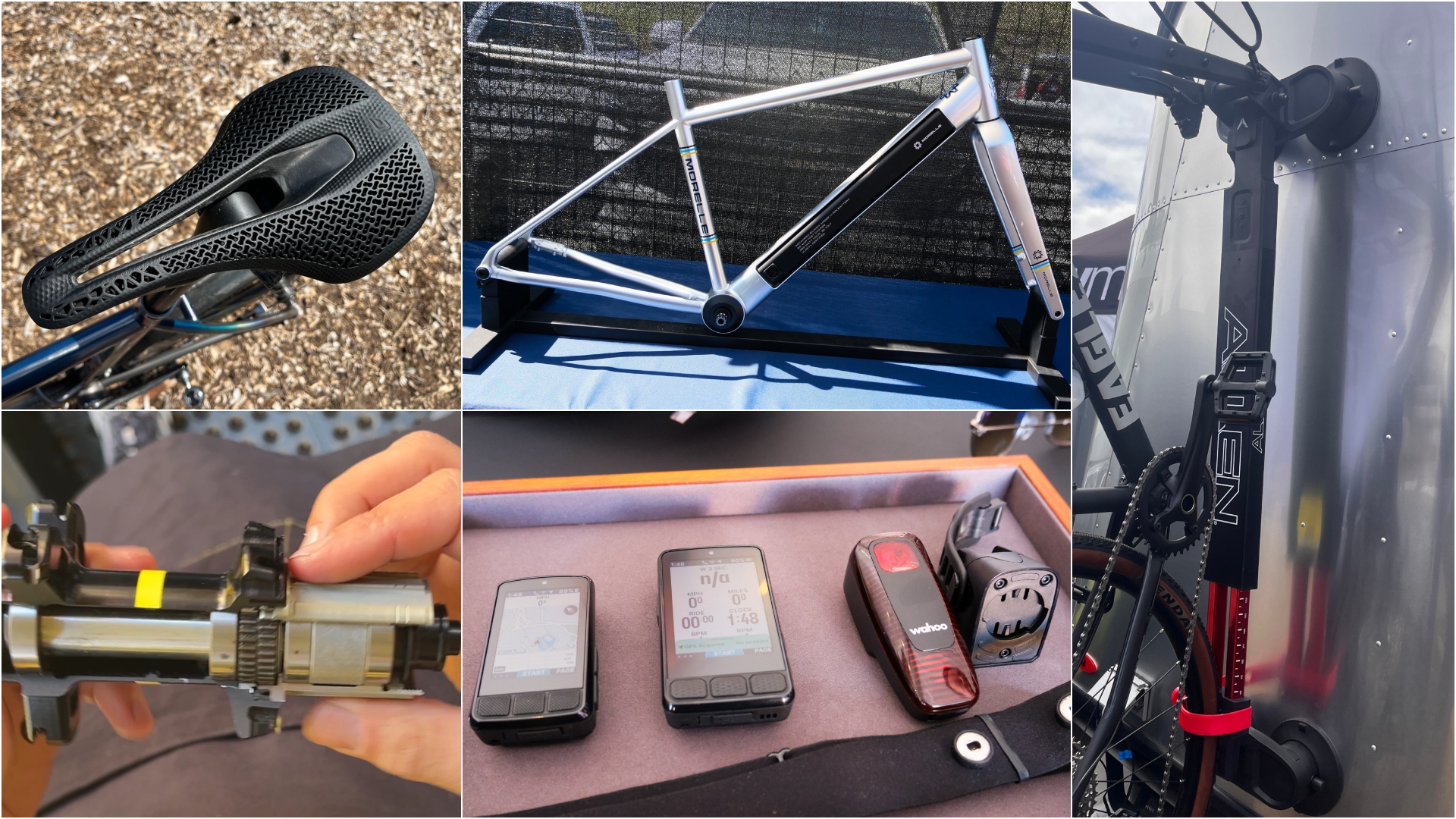

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2A few standout pieces of gear from North America's biggest bike gathering

By Anne-Marije Rook

-

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incident

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incidentCycling's authorities must do everything within their power to prevent spectators from assaulting riders

By Tom Thewlis