The three basic training principles

The recent surge in cycling's popularity has seen a commensurate increase in the amount of advice given to riders on how to train.

Everything from multi-day rides across America to your local 40-minute crit race comes with specific advice on the best way to prepare, be it via books and magazines, online, from specialist exercise coaches or just your club buddies, always keen to give you the benefit of their experience.

With all this information flying around it's hard to know where to start. You hear of riders undertaking complex interval sessions and supplementing their training with special diets and strength-training programmes.

Technical and tactical aspects play a major role in certain events and need to be developed in tandem with fitness increases, but where do you start on day one? What do you need to work on exactly, Strength? Speed? Power? Endurance?

When faced with the sheer diversity of what you need to improve, and the sheer volume of information on how to go about it, riders often suffer a kind of option paralysis where they choose none and end up simply riding their bikes rather than training. Clearly, this is no way to improve.

For this feature we're going help you avoid this pitfall by focusing on three simple principles of conditioning that form the basis for all successful training programmes. Individually they are each of high importance but taken together they form an incredibly potent building block towards quick and sustained improvement.

So integral are they that we can think of them as the holy trinity of training principles, but despite the fact that they are so integral to the success of any training programme - and are fundamentally very simple to grasp - they're are also the ones that most riders find difficult to adhere to or, as we shall see, choose simply to ignore.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Apply these to your training though, and whatever standard of rider you are and whatever your target event, only one thing can happen. You will become a better rider.

The three principles we're going to look at are progression, overload and recovery. But before I explain why they are so vital, it's important to understand the basic concept of training adaptations.

Adaptations

Adaptations are what we strive for when we train. It is a term that describes the changes (hopefully improvements) that both mind and body experience as a result of your training, and the holy trinity of overload, progression and recovery, when applied correctly, help maximise training adaptations.

Look closely at the meaning of the three terms and you'll see there's no rocket science involved here. They simply summarise what most of us with a rudimentary knowledge of training already know to be true: in order to get better you have to push yourself a little harder than is comfortable (overload), gradually increasing training load (progression) until you need to rest (recovery). Easy in principle but as I said, many riders struggle to implement these three simple processes into their training or, worse, ignore them

So let's take a look at each in turn and see how you can implement them and boost your training results.

Overload

This states simply that as you subject yourself to a given stress, be it physical, technical or mental, in order to improve, that stress needs to be greater than the amount you are normally conditioned to deal with.

So overload is simple in theory but demands a clear understanding of how much actual ‘overload' is required. The tendency for many riders is to assume that more is better and they throw all sorts of extra-hard intervals or strength training sets and reps into the mix.

This can lead to premature breakdown as the body and mind struggle to cope with the sudden increase in training stress and both motivation and results fly out the window. This is your classic ‘new starter' at the gym - full of good intentions but does too much too soon, can't sustain it and quickly gives up. Fortunately, principle number two can help us regulate how to apply overload a bit more sensibly.

Progression

Progression means that having achieved some sort of adaptation from a training stimulus and witnessed some improvements, in order to keep on improving you need to continue to overload the system as it has got used to the initial amount of stress and can now handle it quite readily. In plain English you pushed yourself a bit harder, got used to it and are ready to give it some more. But how much?

A good example here is training with power. Using watts as a measure, a rider might begin with a particular set of intervals sustained at 300W. As that rider becomes adapted to this stimulus they'd increase the watts to say 310 for subsequent sessions, then 320 and so on. This is a suitable method for using progressive overload to develop critical power (the amount of power a rider is able to sustain for a given period).

An example of progressively overloading as a technique might be a time trial rider trying to increase threshold pace for a 25-mile time trial in the aerodynamic position. This rider might first develop the ability to sustain their threshold heart rate by gradually increasing the time spent at and slightly above that intensity, then gradually increasing the amount of time spent at that intensity in the aerodynamic ‘tuck'.

This would yield significant, measurable and sustainable improvements over time. However, simply asking a rider new to the competition to complete a 25-mile time trial in the aerodynamic position straight off the bat wouldn't be anything like as effective and almost certainly result in the rider underperforming and giving up the challenge.

You can see that these are good examples of both overload and progression, as they gradually increase the stress levels as the ‘system' be it physiological or technical, becomes adapted. Notice that our power rider in the first example, having become accustomed to the 300W load, didn't suddenly increase to 400W or more.

Instead the increments were much smaller, much more ‘progressive', and therefore the adaptations achieved will be more sustainable. It is often possible to gain large, quicker adaptations with rapid overload but the adaptations tend to be unsustainable and there is a high risk of illness, injury, burnout or overtraining.

Recovery

The ‘R' word is the elephant in the room. Riders don't like to talk about recovery, let alone do any, as it means curtailing the thing they love doing most - riding their bikes.

Surely if progressively overloading your training is the key to seeing adaptations, then the more you do the better you get, right? Yes, but only to a point because without sufficient recovery all those wonderful adaptations we've been talking about won't take place in the first place.

The simple fact is that you don't actually get the adaptations during training. It's when you stop and allow the systems you've been overloading to recover that these adaptations occur and you see something called overcompensation.

This means your mind and body don't just recover to the level they were at before you started the training, they overcompensate and recover to a level where they are prepared not just for the stress you subjected them to previously, but a little extra besides. In short you've become a better rider. (See the overcompensation panel, right).

So despite the fact that we hate not riding, recovery is equally essential to our training as overload and progression. Indeed, take away either side of this training pyramid and the whole thing comes crashing down - this is why as I mentioned that riders often fail to improve because one or more of the sides to this pyramid is usually missing.

How so? Because the majority of our riding is spent in a completely unstructured way with scant respect to any of the above principles.

We often ride with a group because it's sociable and fun. If they go fast, we go fast, if they go slow we go slow. If they ride three times a week so do we. If they do hills we do hills. Then when we ride alone, if we feel good we go fast, if we feel bad, we try to go fast anyway because we love it. And as for recovery, that's just another word for laziness right?

Is this beginning to sound familiar? While there's nothing wrong with simply riding your bike for fun, given what we've just learned you can clearly see that this approach is hardly going to help you improve as a rider. So it's important to make the distinction between simply riding and training.

The training load

Given the power of our holy trinity of good training principles, it makes sense to apply it to as much of our training time as possible. And to ensure that all our training falls into line with these principles it helps to have an understanding of the ‘training load,' which is a simple way of calculating the cumulative effects of the volume of training on your system.

With such an understanding it then becomes easy to ensure that you are overloading and progressing training correctly at the same time as avoiding the chances of overdoing things by getting sufficient recovery.

Look at the diagram below and you'll see that the training load is comprised of three things. Duration, which is how long your training sessions last for. Frequency, which is how often you do them, and intensity, which is a measure of how hard you train when you are doing it. So in order to achieve the progressive overload we're looking for you need to manipulate the training load by increasing the volume and the intensity.

Doing that is quite simple. Volume can be overloaded by increasing either frequency, duration or both, whereas intensity is a case of working harder. As stated at the start of this feature, despite being a simple concept, it's the one that most riders get wrong or ignore.

The commonest failing being (as we've seen) simply to undertake a random series of rides of all kinds of durations and intensities and pretty much going with the flow of how you feel. One of the biggest failings is increasing everything at the same time, especially for riders new to structured training who quickly see big improvement gains and get swept away on a tide of positive endorphins.

They get fitter quite quickly and suddenly a two-hour ride with a couple of hard intervals a couple of times a week becomes a four-hour ride at eyeballs-out pace every day they can find the time to get out.

A better idea would be to examine your rides in the context of our three principles of conditioning and increase either the duration or the frequency one step at a time to ensure progression, before ramping up the intensity to provide the overload.

How much recovery?

The amount of recovery needed is commensurate with the volume of training and this will change as you progress. Using the overcompensation formula (right) is a good place to start, as if you are not able to achieve increases in training volume and intensity following recovery, then the balance between training and recovery needs addressing.

There are a number of tools you can also utilise to help you determine how well recovered you are. Resting heart rate for example, when taken early in the morning, will settle into a pattern during a period of structured training, and unusually high readings on a given morning point to a possible need for extra recovery.

In the initial few months of a training programme, it's quite normal to see your resting heart rate drop considerably, a sure sign that you're getting those training adaptations.

Finally, given the importance of in the holy trinity of training principles, it is clear that the quicker and more effectively you can recover the sooner you can get back to training and the faster you'll improve, so think of it as an active part of your training rather than just ‘sofa time' and utilise as many of the following techniques to speed up your return to training.

- Rest: As it sounds, simply time taken off from physical and mental exercise. Helps both your mind and body recover from the training stresses you place on them.

- Physical therapies: Massage, hot tubs and compression garments are all ways that help speed up the process of flushing toxins from the muscles and simply relieving the soreness of tired legs.

- Nutrition and rehydration: It's essential to refill empty fuel tanks and you need to provide the essential nutrients needed to repair exercised muscles. So ensure a good, balanced diet is maintained during the recovery period. Rewards for your commitment are certainly justifiable when deserved, but don't make the mistake of bingeing in your training down time as a reward for all the hard work you've done.

The Overcompensation model

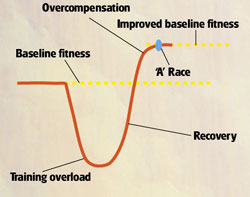

Training adaptations occur following recovery periods that in turn follow periods of training. The overcompensation model illustrates how this works in relation to sustainable, long-term improvements.

Below [diagram one] you can see how balancing the training overload with sufficient recovery results in improved baseline fitness. It's also worth noting here that correct timing of the overcompensation period to coincide with an athlete's ‘A' race will result in a training peak and consequently good form for the event.

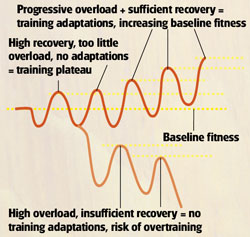

Diagram one Diagram two

In the diagram two above you can see how effectively or otherwise the progressions and recovery result in chronic changes to baseline fitness. Insufficient overload leads to a training plateau, whereas progressive overload and sufficient recovery results in positive training adaptations. Too high an overload, insufficient recovery or in the worst case a combination of both of these things will lead to negative adaptations such as fatigue, loss of form and the potential for overtraining.

This article was first published in the Autumn 2012 issue of Cycling Fitness. Read Cycling Weekly magazine on the day of release where ever you are in the world International digital edition, UK digital edition. And if you like us, rate us!

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.

-

I went to Paris-Roubaix Femmes and was shocked at how it is still treated as secondary to the men’s race

I went to Paris-Roubaix Femmes and was shocked at how it is still treated as secondary to the men’s raceThe women’s version of the Hell of the North is five years old, but needs to be put more on equal footing with the men

By Adam Becket

-

Broken hips, hands, and collarbones: Paris-Roubaix's lengthy injury list lays bare brutality of race

Broken hips, hands, and collarbones: Paris-Roubaix's lengthy injury list lays bare brutality of race"It probably wasn't the best idea to continue," says one of weekend's many wounded riders

By Tom Davidson