A town built for bikes

Believe it not, Houten is not a town from a parallel universe. Neither is it an elaborate and subversive piece of conceptual art which questions and mocks our obsession with vehicular road transport.

No - Houten is real. It exists in our space-time continuum and is a fully functioning, lived-in community of just under 50,000 people that's turned modern urban design inside-out by putting cyclists and pedestrians right back at the top of the pecking order.

Whereas nearly every modern town is built around its vehicular road network, the core bone structure of this place is inversely one of parkland, walkways and cycle paths. Here in Houten, in the flat Dutch countryside just a handful of kilometres south-east of Utrecht, cars are banished to the outskirts and front doors open onto bike routes.

Like Milton Keynes, Welwyn Garden City, Harlow and the like, Houten is a so-called new town which was rapidly expanded out of an older settlement in the latter half of the 20th century.

But while British town planners had all but forgotten the bicycle, the Dutch were already into a phase of reclaiming their streets from the motorcar.

But even by exemplary Dutch standards of cycling provision, Houten is radical.

Designed by architect Rob Derks, the very spine of the place is a cycle path that runs east to west across town and along which most of the schools and important buildings are situated.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

One of these is the town's railway station, which sits adjacent to the central square. When a train comes in, the place resembles a triathlon transition zone. Rather than the usual hustle and bustle of taxi ranks and chugging busses, passengers descend on escalators directly from the overhead platforms to fan out across a huge indoor bike park. Pretty much everyone grabs a bike.

From that main axial cycle route, a whole network of other paths filter off to serve every nook and cranny of the town. Many stretch through their own ribbons of greenery or along reaches of water. Beside one such channel we stopped to peer up at a heron on a rooftop.

Houten about

Riding around Houten on hire bikes, we couldn't help but notice that the scale and pace of the town is so much more human than others. You're not swept up in the rush of vehicles. You need not be on guard for inattentive drivers. You can hear yourself think.

Rather than buzzing traffic, the sounds along the town's main thoroughfares are of bike wheels whirring, muffled far-off talking and birds singing in the trees.

If you want to hear an engine revving, you've got seek it out.

To Dan, our photographer, this was almost unnerving. "It feels eerie, like there's a lurking menace," he noted when we paused at the intersection of two bike paths, sided all round by greenery.

Dan, it turned out, had been watching too much Desperate Housewives and now thinks all quiet patches of leafy suburbia are dens of iniquity.

But perhaps he also had a point. So used are we to our built-up environments, looking, feeling, being engineered around noisy roads, that any deviation from that blueprint puts us at unease.

Revolutionary roads

Houten is not without roads: in fact, there are actually quite a lot of them. However, the town's streets are more like service roads that wind and wiggle around the back of buildings, weaving convoluted routes that both discourage speed and minimise disruption of the cycle and footpath network.

If it's the pedestrian and cycle routes that form the skeleton of Houten, the road network is like its capillary system that feeds in from a fast outer ring road that connects with the greater Dutch road map.

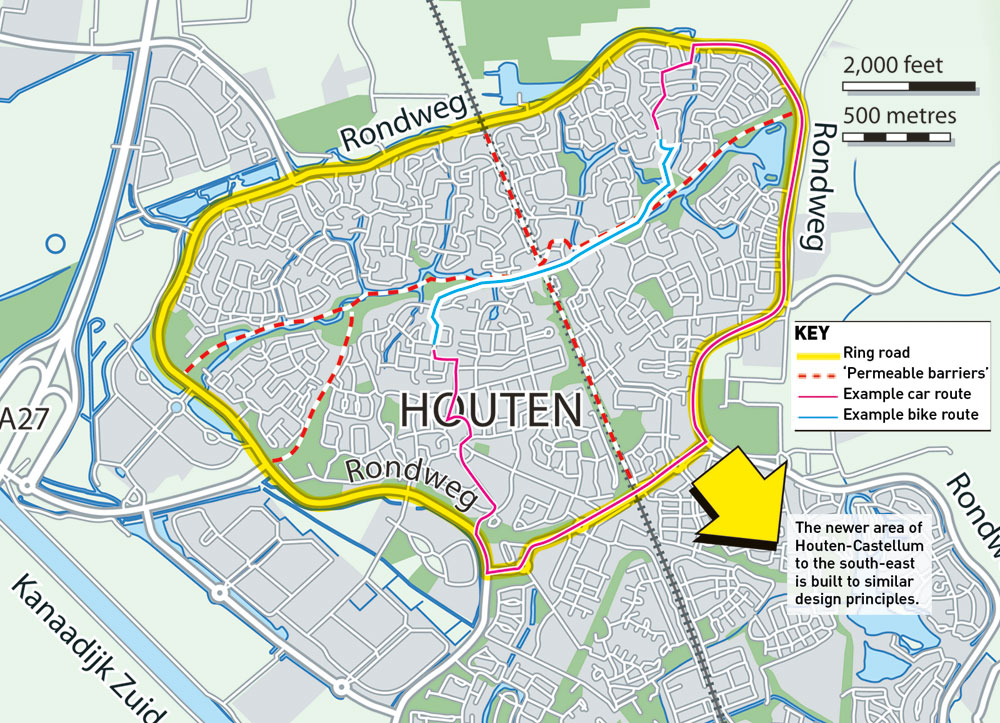

The ring road not only diverts what would be through-traffic around Houten, but carries all potential cross-town traffic. This is because the inner town road network is essentially dissected into segments that only connect via the ring road.

While cyclists and pedestrians can breeze across these thresholds on their multitude of paths, to access another segment by car requires retreating to the town's orbital and going the long way round.

The basic upshot of all this is that inhabitants can use cars for the purpose they best serve: longer journeys, to remote locations or when travelling with significant loads. But for local run-arounds, trips across town, commutes and nights on the tiles, the bike is the better, more convenient option. The town seems all the better for it.

‘Permeable barriers' - bollards and gates passable by bikes and pedestrians but not by cars - divide Houten's road network into five segments. While cyclists can ride directly between points A and B, cars have to retreat to the ring road and take the long way round.

How to build a bike-friendly town

André Botermans is a planning engineer with the City of Houten's council

CW: What was Houten like before it expanded in the 70s?

AB: Around 1970, Houten was a small village with approximately 3,000 residents, surrounded by a wide-open agricultural area mainly used for fruit cultivation.

What is the design inspired by?

AB: The design of Houten is extracted from natural, organic forms and structures. The structure of the primary bicycle routes is comparable to the trunk of a tree with its system of branches and leafs coming off it. The experimental separation of slow and car-traffic is still a unique feature. There is no other city in the world with such a consistently designed and built urban structure.

Does the design work as expected?

AB: The design works very well. Houten has grown to be a very popular and people-friendly town, especially for families and young children. Year after year, Houten scores very high in ratings of satisfaction and attractiveness.

What do you like best about Houten?

AB: The human scale of the place and that the town has remained very low profile, unpretentious and modest.

Does the design create any problems?

AB: When the town was first built, there was little local employment so the people who came to live in Houten worked elsewhere. That's more of a spatial planning issue on regional and national level, and the change of culture, especially in relation to the possession and use of cars. Despite the residents in Houten being very bicycle-minded and bicycle use very high, the car is still very dominant.

What happens in emergency situations? Do the permeable barriers restrict access to emergency vehicles?

AB: No, emergency vehicles are allowed to take shortcuts from one residential area to the other.

Do you think this model could be applied elsewhere?

AB: Absolutely, it's a matter of smart design. On the other hand, it's very hard to apply the design principles in an existing town.

This article originally appeared in the March 21 2013 issue of Cycling Weekly magazine

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

-

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much more

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much moreSupported It's not just Bontrager, Balfe's has a huge selection of discounted kit from the best cycling brands including Trek, Specialized, Giant and Castelli all with big reductions

By Paul Brett

-

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-Liège

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-LiègeUno-X Mobility to rebrand as 7-Eleven for Sunday's Monument to pay tribute to iconic American team from the 1980s

By Tom Thewlis