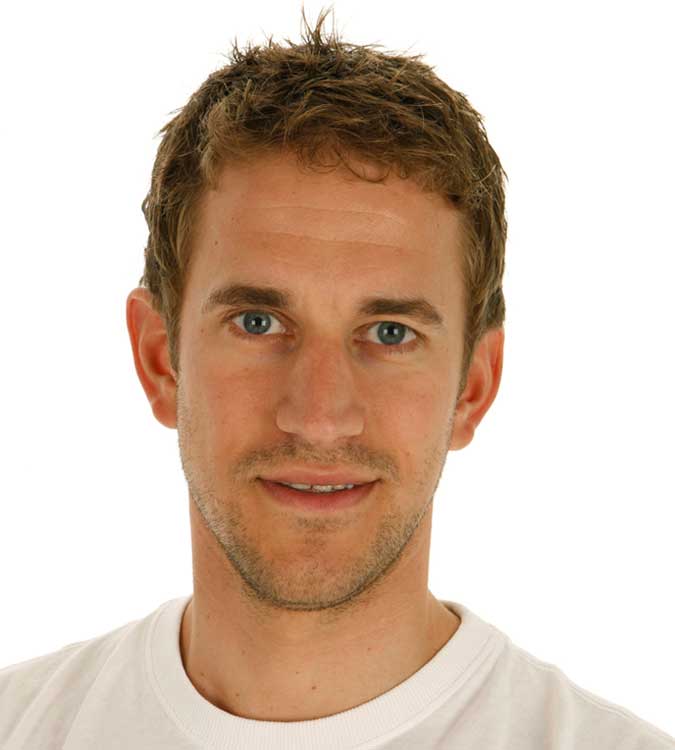

Chris Walker: British Legend

Shane Sutton knows a thing or two when it comes to identifying talented bike riders. He has played a significant role in Britain's cycling revolution in recent years and built a world-renowned reputation for being able to see the potential in riders that other coaches or team managers may overlook.

In his racing days, Sutton was a team-mate of Chris Walker at Banana-Falcon, so there is no one better to give a judgment on him.

>>> Subscribe to Cycling Weekly and be at the heart of the British cycling scene

"We had a really talented bunch of riders at Banana-Falcon," says Sutton. "But there's no doubt that Chris was the special one. I shudder to think what he could have achieved in the modern era with all the benefits of the support structure we have in place now. He had it all and could win any type of race. A mega talent."

High praise indeed when you consider the calibre of riders that Sutton has worked with over the years. Walker was widely regarded as one of the most talented British riders of his generation. It's easy to see why.

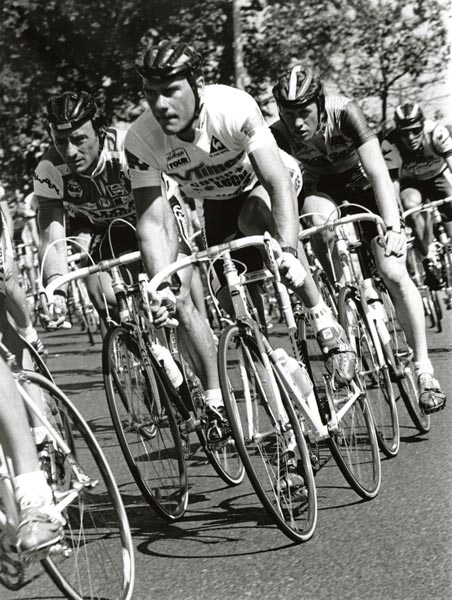

He won numerous crits (he was also twice British crit champion); the 1991 Milk Race, which he and his Banana-Falcon team dominated from start to finish (Walker won five stages that year plus the points and combine jerseys); plus a whole host of wins in single-day races. Walker regards his four stage wins in the 1991 Settimana Bergamasca as his career-best performance.

Knee to know

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

However, but for a twist of fate (or more accurately a twist of a knee), Walker could have become a runner instead of a cyclist. He started running because his dad ran and was doing long distance races from about the age of 11. When his dad suffered a knee injury and took up cycling instead, Chris, then aged 13, followed suit.

His first bike - a Carlton Continental - became his pride and joy and he would spend hours making sure it was in mint condition and the rest of the time riding it around the beautiful but challenging Yorkshire countryside: "Cycling just captured my imagination and one day I was out riding, I met a guy from a local club - Beighton Wheelers - and joined them."

His first taste of racing was in 10-mile time trials but it wasn't until he did his first crit that he really caught the bug. Walker went on to become one of the few riders to have won the National Junior Road Race Series twice.

"Everything was going to plan and I couldn't see anything stopping my progress," he recalls. "I was a bit naive, but I believed I could do anything in the sport, so at 19 I went to race in Italy to pursue a pro career."

In his first race Walker finished second to Franco Ballerini, who would go on to win Paris-Roubaix in 1995 and 1998. He won three races in Italy and hoped that it would open the door to a pro career with a big team, but it also opened his eyes to doping in cycling. He was offered a contract with the Fanini team but he turned it down and returned to England to get away from the doping culture he encountered in Italy.

Walker was determined to always race clean and joined the Paragon team set up by his dad to help young riders win pro contracts. It did just that and in 1987 Walker signed for Water Tech-Dawes, which meant that he was racing alongside two riders he had always looked up to - Sid Barras and Keith Lambert (the latter was also the team manager).

Walker made a big impact in his first season, his highlights being a win in the TV Times Sprints competition of the inaugural Kellogg's Pro Tour of Britain, and the PCA's Best New Pro award. "That was a brilliant year," says Walker. "To be getting paid to do something I loved was a dream come true."

He joined Raleigh-Banana in 1988, a strong squad managed by Paul Sherwen and including Adrian Timmis, Chris Lillywhite and Dave Rayner. Walker won nine races in two years with the team, but neither he nor the squad realised their full potential.

Fruitful time

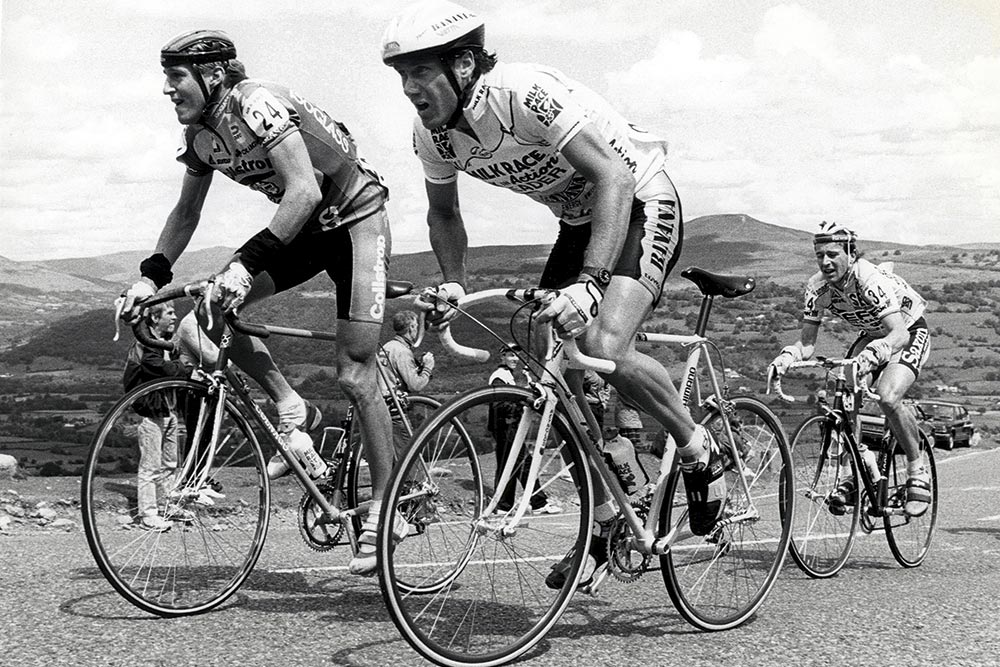

In 1990, he joined Banana-Falcon - managed by Keith Lambert - a team for which Walker would produce his best performances.

"I have a lot of time for Keith and he certainly helped me to develop as a rider," says Walker.

He won four stages of Italy's Settimana Bergamasca stage race. Lance Armstrong - aged 20 - was the overall winner.

In 1991, Walker led the Milk Race from start to finish and picked up five stage wins. "It was a relief to win after the pressure of defending the jersey from the first stage onwards. The team was really strong all through the race," he explains.

Walker says he never considered himself to be a stage racer and this comment is one of many in our interview that hints at a lack of belief in his own ability. There is a sense from talking to Walker - and those who raced with and against him - that he had more talent than he had realised at the start of his career.

Stateside stint

Walker left Banana-Falcon at the end of the 1991 season and spent two years racing for American teams aiming to break into big-time European racing. He won races, but the big plans for the teams didn't work out while he was there.

By 1995, he was considering retiring, but Shane Sutton persuaded him to carry on as Sky were sponsoring a TV crit series in Britain. Walker - racing with Sutton for Peugeot UK - won the series but celebrations after winning one of the televised races in the Isle of Man could have cost him a chance to win the British road race title the following day.

"I was focusing on the crits so I didn't have any ambitions in the road race," says Walker. "I was just there to help the team and cover any early moves so the night before I went to a party and had a few beers too many."

On the last climb, he was clear with Robert Millar. Walker responded to Millar's attacks and fancied his chances of outsprinting the Scot after the final descent.

"We only had one little rise to the top of the climb when he attacked again and I got cramp. I've never had cramp in a race before," Walker says.

Millar went clear and won what was to be his last race as a pro. Walker was pleased to win a silver medal - his best performance in the national road race - but was left to wonder whether a cup of Horlicks and an early night might have turned that silver into gold.

Cautionary tale

"It's the kind of story I tell my kids so that they can learn from my mistakes," says Walker, who now helps his son Joey and daughter Jessie, who are both talented racers.

After a decade of proving he was one of the best - if not the best - crit rider of that era, Walker finally won the national crit title while riding for Team Brite in 1998. He retained it the following year while racing with the Linda McCartney team. Wins in the Archer GP and GP of Essex proved to be final flourishes of his pro career. He did a few races in 2000 but his heart wasn't in it any more and he retired from pro racing at the age of 35.

Motorcycling has always been one of Walker's passions and he put this to good use working with the RST motorcycle clothing business where he is now a product designer. RST has its own line of cycle clothing, too.

Chris Walker comes from a family of riders

Mixed feelings

Despite some big wins Walker has mixed feelings about his pro racing days: "Cycling for me was big highs and big lows. I don't have a romantic view of cycling."

Recent revelations have brought back Walker's own feelings of resentment about racing against riders who cheated. He says: "I know it sounds like I'm making excuses, but it does feel like something was stolen from me."

He still remembers races - such as two stages in the 1991 Milk Race - where stage wins were awarded to him after the rider who crossed the line first was subsequently stripped of those wins. In the record books, his name is there as the stage winner, but the fact that he never got to punch the air when he crossed the line still irks him. He could have become bitter and cynical. Instead, he has been encouraged by the success of the British Cycling programme and Team Sky and believes cycling is heading in the right direction.

"When I see guys such as Swifty, Wiggo and Cav winning it makes me feel better because I can see that things have changed for the better. It gives me hope to encourage my kids in the sport."

Chris Walker: Highs and lows

Walker is remembered by most fans for his 1991 Milk Race win - a race which he led from start to finish. However, Walker considers his four stage wins in the Settimana Bergamasca as his best performance. Either way, there's no doubt that 1991 was by far his best season as he also won a stage of the Tour of Vaucluse.

Understandably, the day when, as a 19 year old, he was first confronted by the darker side of cycling is the low point of his career. In these cynical times, it's worth highlighting that it's easy to find riders who rode with and against Walker who hold him up as a clean rider.

He wasn't the only one to race clean in the 1980s and 1990s, but his story is a timely reminder that those who chose to compete within the rules paid a heavy price for trying to uphold the integrity of pro racing.

The darker side of cycling

Walker was confronted by the dark side of pro cycling when he went to race in Italy in 1984 at the age of 19.

"As soon as I got there they took me to see a doctor. I thought I was going for a medical check-up but the doctor gave the team manager a box for me that was full of ampoules and syringes. I made it clear I didn't want anything to do with it."

The knowledge that some big teams expected riders to dope affected him for years. He's happy that he always raced clean and never allowed himself to get dragged into the doping culture, but he still feels aggrieved when he thinks of races when he was narrowly beaten by riders who he knew were cheating. However, he now feels that cycling is cleaner than it has ever been.

"People who I've known for years, who I trust, tell me that the sport has changed for the better."

Racing with Bradley Wiggins

Walker raced for Team Brite in 1998, a squad that represented a watershed in British cycling as it included champions from the era when successes at World Championships were rare, and those who would go on to play a part in transforming our status as a cycling nation.

There was 1989 individual pursuit world champion Colin Sturgess, who was coming towards the end of his career, while Jonny Clay, Rob Hayles and Chris Newton would win world and Olympic medals as Britain emerged as a track powerhouse. And there was Bradley Wiggins - then aged 18 - who had won the individual pursuit at the 1997 Junior World Championships.

"I remember congratulating him on his world title when we first met," says Walker. "We're used to seeing Brits win world titles now but back then it wasn't expected. Even then there was something special about his personality. He says he's just an ordinary bloke, but he's always had that presence about him."

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Editor of Cycling Weekly magazine, Simon has been working at the title since 2001. He fell in love with cycling 1989 when watching the Tour de France on Channel 4, started racing in 1995 and in 2000 he spent one season racing in Belgium. During his time at CW (and Cycle Sport magazine) he has written product reviews, fitness features, pro interviews, race coverage and news. He has covered the Tour de France more times than he can remember along with two Olympic Games and many other international and UK domestic races. He became the 130-year-old magazine's 13th editor in 2015.

-

'This is the marriage venue, no?': how one rider ran the whole gamut of hallucinations in a single race

'This is the marriage venue, no?': how one rider ran the whole gamut of hallucinations in a single raceKabir Rachure's first RAAM was a crazy experience in more ways than one, he tells Cycling Weekly's Going Long podcast

By James Shrubsall

-

Full Tour of Britain Women route announced, taking place from North Yorkshire to Glasgow

Full Tour of Britain Women route announced, taking place from North Yorkshire to GlasgowBritish Cycling's Women's WorldTour four-stage race will take place in northern England and Scotland

By Tom Thewlis