Classic races: 1990 Tour de France

An early escape turned the 1990 Tour de France into a three-week game of catch-up for reigning champion Greg LeMond. Would he repeat the previous year's victory, or had he left it too late? Cycle Sport spoke to all the chief protagonists to piece together the story of one of the most dramatic races of all time.

Words by Lionel Birnie

Photography by Graham Watson

No one was expecting a repeat of the drama of the previous year, when the Tour de France was decided in the final metres on the Champs-Elysèes. But the 1990 Tour was just as gripping, albeit in a different way.

Instead of a final-day showdown, there was a three-week pursuit around France. And all because the contenders wanted to save their legs on the first Sunday. With a team time trial to come in the afternoon, four riders gained 10 minutes during the morning’s road stage. And it took almost three weeks to get that time back.

**

The Tour began at Futuroscope, a futuristic theme park near Poitiers, intended to showcase French technology and innovation. This being a late-1980s vision of the future, it had a surreal feel that wasn’t eased by the fact it was stuck out in the middle of nowhere. It was the sort of place that probably looked a lot better during the design phase but the finished park ended up as a vision of the future restricted by the realities of the present. Disneyland without the cartoon characters.

Futuroscope had hosted a time trial in the 1987 Tour de France, shortly after the park opened. Now the owners had paid £500,000 to stage the opening weekend. “It was like something from space,” says Frans Maassen, the Dutch rider with the Buckler team. “It was strange and there were bits of it that were still like a building site.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Before the race, French newspaper L’Equipe was anticipating another showdown between Greg LeMond and Laurent Fignon, the two men separated by just eight seconds in Paris the year before. LeMond, the reigning world champion, had not won a race since taking the rainbow jersey in Chambéry the previous August, while Fignon was horribly out of form. Before the race the two adversaries had been sniping at one another. Fignon said: “Greg’s tactics don’t change. He always bases his race on following the most dangerous rider on general classification, never attacks and saves himself for the time trials.”

The other two firm favourites for the race were Pedro Delgado, the 1988 champion and Erik Breukink of Holland.

Thierry Marie, a team-mate of Fignon’s on the Castorama squad, won the prologue. There’s always a sense of relief to finally get started after all the build-up and the favourites just wanted to settle down and negotiate the dangers of a flat, potentially windy opening week before the first serious battle came in the time trial at Epinal. As it turned out, the race was to take an unusual twist perfectly in keeping with the alien surroundings.

**

On the first Sunday there were two stages, as was common at the time. In the morning was a 138-kilometre loop, followed by a 45-kilometre team time trial in the afternoon. Most of the riders disliked the split stages because there was very little time to recover before having to ride in a hard, specialist discipline. For Steve Bauer, this presented an opportunity.

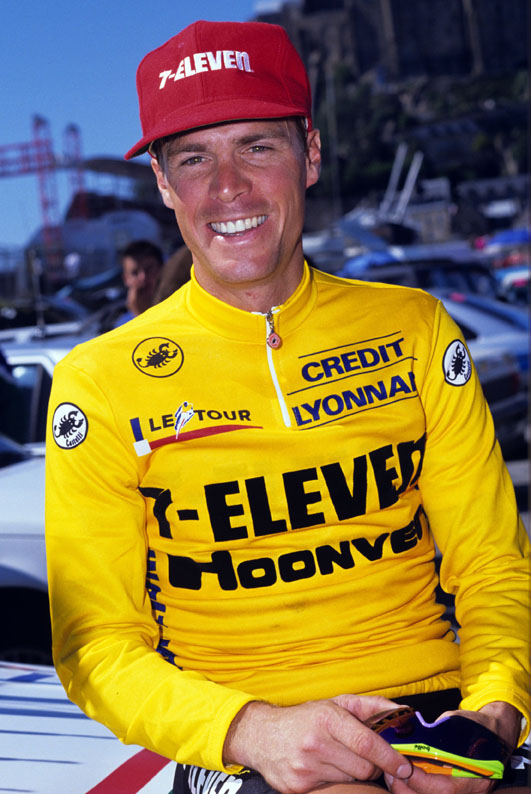

“When you have a team time trial in the afternoon, you don’t have the same commitment from the teams in the morning,” said the Canadian, who rode for 7-Eleven. “Everyone knows that if you have a bad team time trial you can lose a couple of minutes, so no one really wants to go into it feeling tired already. My tactic was simple: attack and hope that there wasn’t the stomach for a big chase. I did exactly the same thing in 1988 when I attacked in the morning stage, won and got the yellow jersey. I wanted to use it to my advantage again. I told myself that from the gun I had to be in every break. You don’t want to miss the one that eventually goes.”

Claudio Chiappucci, a 27-year-old Italian rider with the Carrera team, was virtually unknown outside his home country but, after a solid Giro d’Italia, he had his eyes on an early spell in the king of the mountains jersey.

“We planned the escape,” he says. “When we arrived in France we examined the [route] book and I saw there was a chance to get away, win the points for the king of mountains and get on the podium on the first day.”

As soon as the flag dropped at the end of the neutralised zone, the attacks started. Even with the team time trial looming, everyone was eager and fresh. Bauer had positioned himself right at the front on the start line so he could see everything happening in front of him. There’s a touch of alchemy in the way a successful break forms. It takes boldness, persistence and a stroke of luck to be in the right place at the right time. But not until the combination of riders and circumstances is perfect will the break turn to gold.

Chiappucci and Bauer were joined by Maassen, and Frenchman Ronan Pensec, a team-mate of LeMond’s in the Z squad. The gap was small to start with, just 30 seconds or so, and it stayed like that for 20 or 30 kilometres. The bunch could see the riders ahead but couldn’t bring them back.

Maassen rode for Buckler, run by Jan Raas. “We did the Tour of Sweden just before the Tour,” says Maassen. “We won four stages but we made a silly tactical mistake and lost the race overall to an amateur rider [Dimitri Zhdanov of Russia]. Raas was angry about that. He was often angry about things. Sweden was not a really important race so maybe he was angry about it to motivate us for the Tour. Before the race he kept saying how important it was for us to have a good start. We had a new sponsor [Buckler, a brewer of non-alcholic beer] and Raas wanted to impress them.”

The chase was disorganised and the gap was just big enough to discourage anyone from trying to bridge across, the effect of which would have been to drag the whole peloton up. In the escape, no one dared look back for fear of seeing the bunch upon them. It became a case of willpower. Could the escapees keep the pace up until the bunch sat up?

“We were drilling it but we knew in our minds we couldn’t keep that pace up for ever,” says Bauer. “It became a case of who was going to break first? Us, or the peloton? We didn’t want to give up but it was getting to the point where we were pushing very hard and getting nowhere. I don’t know what was happening behind but eventually they stopped chasing and suddenly, boom, we had five, six, seven minutes.”

Back in the bunch, no one wanted to work for fear of compromising their team time trial. LeMond’s Z team had the perfect excuse – they had Pensec in the lead. Castorama, who were supposed to be defending Marie’s yellow jersey, had their minds on the afternoon stage. Panasonic, run by Peter Post, who was Raas’ nemesis, hated the fact a Buckler rider was up the road. But they, too, were saving themselves. That left PDM, who had Breukink and Raul Alcala as their leaders. They took on the bulk of the work but only once the gap had reached 15 minutes, by which time it was damage-limitation time.

“I was really worried Panasonic would chase,” says Maassen. “I was sure they wouldn’t let me get away because we always had big bells [ding-dong battles] with them. In those days it was always Post against Raas. It cost me a lot of races. I heard from some guys afterwards that Post was very angry with them that I had been allowed to get away.”

Chiappucci achieved his goal, winning both of the climbs to take the lead in the king of the mountains competition. Bauer knew he had ridden the best prologue time trial of the four. However, Maassen won the time bonus at the first intermediate sprint and Bauer knew that if the Dutchman won the stage, he’d also take the yellow jersey. “I made sure I won the last bonus sprint because then I just had to finish with Maassen and I’d get the jersey,” he says. “My main goal was to get the yellow jersey but once I’d made pretty sure of it I did start to think about the stage as well.”

On the run-in, Pensec stopped working. Even for Z the lead had grown a little uncomfortable. By now Maassen felt the pressure to win. “I was worried about Bauer,” he says. “Chiappucci I knew nothing about. I hadn’t heard of him but I thought ‘well, he’s Italian, he’s a little guy, I think I’m going to be faster’.”

Bauer and Maassen had a chat – each was most worried about the other.

“I felt Maassen was the strongest,” says Bauer. “I didn’t think Pensec was going to try to pull a sprint after he’d sat on the back for the last bit. I said to Frans that if he attacked I wouldn’t chase him.” Bauer hoped that Maassen would attack first, forcing Chiappucci to close the gap and giving him the chance to spring past. It didn’t quite work out. Instead, the crafty Maassen waited, forcing Bauer to lead it out, and then the Dutchman came past to win the stage.

The bunch came in 10 minutes and 35 seconds later. It was a huge gap and however much the likes of LeMond tried to play it down, it was to shape the entire race.

“People these days wonder why we let a four-man break with Chiappucci and the rest go up the road,” says Delgado. “But, frankly, things like that happened all the time in the Tour in those days. It wasn’t so finely calculated as it is now. Also, in 1990, there wasn’t a clear ‘patron’. We all sat around, as it were, waiting for somebody else to start doing the hard work. And nobody did.”

Bauer, fourth overall in 1988, was suddenly being talked of as a contender. He certainly wasn’t the sort of rider you could allow such a head start to. Pensec was also a danger. He was a reasonable climber, and had been sixth overall in 1986, and seventh in 1988. Maassen was not a danger. He couldn’t climb or time trial well enough. But no one paid much heed to Chiappucci. Just a small name. An Italian rider on a Carrera team that had seen better days.

No one suspected it would take the best part of three weeks to reel him in.

**

As he tried to recover for the afternoon’s time trial, Bauer was concerned that the tiny, two-second advantage he held over Maassen would not be enough. On paper, Buckler should have been faster than 7-Eleven. Like the other Dutch teams, Panasonic and PDM, they had made team time trialling a speciality. “I was convinced I would take the yellow jersey in the afternoon,” says Maassen. “The gap was only two seconds. I knew 7-Eleven were strong but I thought we were stronger.”

Powered by Sean Yates, 7-Eleven finished sixth, eight seconds in front of Buckler. “Sean could go toe-to-toe with anyone in the world in the team time trial,” says Bauer. “I certainly didn’t have the full sharpness after the morning stage but I am not one to skip turns. The inspiration of riding in the yellow jersey and knowing you have to go very fast otherwise someone is going to take it from you meant we gave it everything we had.”

Maassen was devastated. “That evening I didn’t celebrate at all. No Champagne, nothing. It was special to be in the break and win the stage but at the time I was so upset not to get the yellow jersey. You know the chance to wear it maybe comes only once in your career. That was my chance.”

To make matters worse, Panasonic won the team time trial. You could say the match ended one-one between Panasonic and Buckler but for Raas it felt felt like they’d led for 90 minutes before conceding a last-minute equaliser.

**

The first week was long and difficult. Fignon crashed on the stage to Nantes, prompting Robert Millar to say: “He’s going badly. He’s always at the back when it gets hard. First possible excuse he gets, he’ll pack.”

There were crashes on the run-in to the stage to Mont-Saint-Michel, off the coast of Normandy and then the riders braced themselves for a 301-kilometre stage from Avranches to Rouen. In the rain. It was the straw that broke the camel’s back for Fignon. He went home.

At Epinal, LeMond had did not do as well as expected. Raul Alcala, the Mexican, won the 61-kilometre time trial by almost a minute-and-a-half from Miguel Indurain. It was an immense performance and had people touting him as the man to beat. LeMond was only fifth, only 15 seconds quicker than his team-mate Pensec.

“I was surprised how well Pensec did,” says Bauer, who retained the yellow jersey by just 17 seconds. “He did a brilliant ride. After I’d finished I was a bit disappointed. I was a bit too conservative that day. I wasn’t really super, certainly not as good as I was in 1988, but I felt I could have squeezed a bit more out of myself.”

Alcala may have been more than seven minutes behind Bauer, but he was now 2-50 ahead of LeMond. However, suddenly being in such a strong position may have been his downfall. Alcala liked to be the underdog, and his position as the outright favourite began to weigh heavily on him.

As the race reached the Alps, Bauer faded. “Maybe the mountains were too tall for me that year,” he says. “Holding the jersey for so long definitely took some snap out of me. I wasn’t following the best guys. I’m not like a top, top climber. I could hold my own when I was absolutely super but I wasn’t quite there.”

At Mont Blanc, Bauer was dropped and saw the lead pass to Pensec. “I found it most interesting, that shift of attention when you’ve lost the jersey, it’s quite dramatic,” he says. “People always ask what wearing the yellow jersey is like and it’s incredible but I don’t think you realise what it means until you lose it. It’s an icon and people are drawn to it. When you have it, you have no time to yourself. Everyone wants a photo or an interview but the morning after you’ve lost it you can cruise around the start village and no one gives a shit. I remember really reflecting on that difference very vividly.”

Pensec took the yellow jersey on his 27th birthday but was under no illusions that he was the Z team’s best chance of winning the Tour, despite what the French press said.

“It was a thrill but I also knew my place. I knew I could never win and that Greg was the team leader,” he says. However, for a couple of days, the Z team had split responsibilities. Most of the team remained assigned to LeMond, but Robert Millar looked after Pensec, pacing him on Alpe d’Huez to defend the jersey. “He worked especially hard for me that day, encouraging me, and I hope he knows how much that means to me.”

As those who knew him suspected he might, Alcala blew up spectacularly on Alpe d’Huez. A dangerous move went clear on the Col du Glandon. LeMond, Delgado, Miguel Indurain and Gianni Bugno broke away and PDM missed it. They gave chase on the descent and then Sean Kelly dragged Alcala and Breukink to within striking distance of the leaders. Breukink remained calm, whereas Alcala was all fidgety and nervous, worrying that his chance to win the Tour was slipping away. When it came to the lower slopes of the Alpe, Alcala was spent and he lost more than five minutes.

“In a way it helped me that we were behind,” says Breukink. “I knew the leaders were not too far ahead and I didn’t panic. It meant I could ride the climb at my own rhythm. I was passing people all the way and that gives you a lot more confidence.”

When Breukink won the mountain time trial to Villard-de-Lans the following day, he became the favourite. “The climb was good for me, not too steep, and I was climbing well. When I won, I thought I could win the Tour, especially when I saw that I’d beaten LeMond by a minute.”

The ride of the day was by Chiappucci, who finished just nine seconds behind LeMond and took yellow. Time was running out for Breukink and LeMond to close the seven-minute gap.

**

No one could guarantee Chiappucci would crack. While it was true he was an unknown quantity, he had shown in the Alps that he could limit his losses effectively. There was just one summit finish remaining, at Luz-Ardiden in the Pyrenees, and the final time trial at Lac-de-Vassivière, on a very demanding course that LeMond knew well, having won there in 1985.

Even if LeMond and Breukink could be confident of taking three minutes in the time trial – and that was far from a certainty – it still left a lot of time to make up, and few opportunities to do it.

After the rest day came the 13th stage, from Villard-de-Lans to Saint-Etienne. It was not long, just 149 kilometres, and it featured just a second-category climb, the Col de la Croix de Chaubouret, but LeMond and his team-mates decided to pile pressure on Chiappucci and hope to catch him cold.

“The stage is one I feel goes unnoticed when people write about the 1990 Tour,” says Pensec, who was now second overall. “I attacked straight away and got a breakaway going which meant that Chiappucci’s team had to chase the whole time.”

It wasn’t until the foot of the Col de la Croix de Chaubouret that Pensec’s group was caught. Chiappucci’s team were tired and the Italian was left exposed. He’d been worked over good and proper.

“I lacked experience and friends in the peloton,” he says. LeMond attacked, Breukink and a few others followed and they quickly gained time. For long spells Chiappucci was all by himself. At the finish Eduardo Chozas of Spain won the stage but Breukink and LeMond were more interested in the time gap. By the time Chiappucci arrived in a group of a dozen or so riders, almost five minutes had elapsed.

“That was a super fast stage,” says Breukink. “I knew I had to be aware because LeMond’s team were attacking from the start, including LeMond himself. People say LeMond was a defensive rider, that he didn’t attack, but he was very intelligent. He was strong but he didn’t waste it. Instead he waited for the moment. The stages around St Etienne are always hard, especially when it’s hot. Chiappucci would have been expecting an attack in the Pyrenees but we had to try to get some time when he wasn’t expecting it.”

Delgado says: “LeMond was a great strategist. He just waited and waited for his moment throughout the entire Tour and then pounced. His rivals were far less experienced than him, or plain unlucky, like I was. Bugno and Indurain were on the point of breaking into the big-time but hadn’t quite made it. Breukink couldn’t handle the heat. At the same time, LeMond had all the luck in the world. If it hadn’t been for that stage to St Etienne, I’m still convinced Chiappucci would have won the Tour. It was a good attack but I sat there, waiting for Chiappucci to go for it. And he didn’t react. I couldn’t understand it. That was the beginning of the end – he missed a move he shouldn’t have.”

**

Although severely compromised, Chiappucci refused to lie down. The crucial stage was going to be a Pyrenean monster, 215 kilometres from Blagnac to Luz-Ardiden, crossing the Aspin and the Tourmalet. With just two minutes’ lead, he was now vulnerable. More or less everyone now accepted that the Tour was either LeMond’s or Breukink’s. It would be close but there was no way Chiappucci would defend that lead in the time trial.

So Chiappucci decided to attack on the Col d’Aspin, breaking clear with a group and turning the spotlight on LeMond instead. It was insouciant riding and the French fans were delighted.

Breukink suffered a disastrous day. He punctured before the Aspin and had to change his bike twice. Because of the aggressive racing up ahead, he struggled to get back in touch and five kilometres from the top of the Tourmalet, he blew.

By now Chiappucci was becoming more than a minor irritation to LeMond. Although the gap was never more than two minutes, it was seriously harming LeMond’s chances. It wasn’t until the town of Luz-St-Sauveur, at the foot of Luz-Ardiden, that LeMond’s group caught Chiappucci’s. On the climb, Fabio Parra attacked, LeMond and Indurain went clear and the American seemed, at long last, deep into the final week, to be on his way to the yellow jersey.

However, Chiappucci was dogged and clung on to the lead by his fingertips. It had taken 15 stages for LeMond to recover ten-and-a-half-minutes. He now had five days to get the final five seconds.

Breukink was now out of it. “On Luz-Ardiden I felt a bit better but by then it was too late. The problem was they were racing full gas when I was trying to get back. That was the day I lost the Tour.”

Delgado too, was no longer a factor. Towards the end of the second week he began to suffer with an upset stomach. At Millau, he attacked towards the finish but admits: “I attacked more so I could get to the finish line as quickly as possible than because I was trying to drop my rivals. At the end of the stage, one of Spain’s top journalists kept asking me for a few quotes and I kept yelling at him that it wasn’t possible. When I rushed off into a field next to the finish and started doing what I had to do, I think he finally realised why.”

LeMond was now on course for his third Tour de France title but it was Chiappucci who had prolonged the suspense. Even with his lead hacked away to almost nothing, he was still upbeat. Max Sciandri, his team-mate, was riding his first Tour. “Every night we were having Champagne and people said ‘Hey, it’s not always like this, you know’. For me, it was strange. I was just trying to survive the Tour and although I tried to help him where I could, there was a limit to what I could do. People love it when the yellow jersey attacks, and he was a very optimistic guy. He probably knew he wasn’t going to win, but he wasn’t going to give up.”

Chiappucci was not universally popular in the peloton later in his career. During the final stage in the Pyrenees, he angered LeMond with a piece of riding that was a violation of the unwritten rules.

Even though it wasn’t strictly necessary, with the time trial still to come, LeMond wanted to gain some more time and take the yellow jersey if possible. The 17th stage from Lourdes to Pau went over the Aubisque and the Marie-Blanque but there was a long descent and flat run-in to the finish. The plan was to put a couple of Z riders – Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle and Atle Kvalsvoll – in the early break, then for LeMond to attack Chiappucci on the climb, make contact with his team-mates and pull out some more time on the flat.

As they reached the Marie-Blanque, Duclos-Lassalle and Kvalsvoll were in a group that was more than seven minutes ahead. They were over the top and on the way down the other side when LeMond punctured on the climb. At that moment, Chiappucci, together with several Carrera team-mates, accelerated.

LeMond had just two men with him – Eric Boyer and Jerome Simon – so Roger Legeay, the Z manager in the team car behind LeMond radioed ahead to Serge Beucherie, who was following the lead group and told him to get Duclos-Lassalle and Kvalsvoll to stop and wait.

“At first we turned round and started to ride back up the course, but they stopped us from doing that because it was against the rules,” says the Norwegian Kvalsvoll. “So we had to wait, for seven minutes. We saw Chiappucci’s group come past and then a minute-and-a-half later Greg was approaching. There were five of us chasing and we all worked, including Greg. It wasn’t just Chiappucci - Breukink and Delgado were up there too but they had more fair play. They didn’t work. It took us quite a while to catch then and I’d never seen Greg so mad. When we caught them, he wanted to attack straight away but we managed to calm him down.”

LeMond was livid that Chiappucci had sought to exploit his misfortune although Breukink is willing to give the Italian the benefit of the doubt. “Maybe Claudio already had it in his mind to attack at that moment,” he says. “It was the last difficult mountain of the race and even though there were still 50 kilometres to go afterwards he was entitled to attack if that was his plan, I guess.” But would Breukink have done the same? “I don’t think I’d want to win the Tour like that. I knew LeMond had punctured. Of course there was no way we were going to wait with LeMond, we had to follow Chiappucci, but we didn’t work.”

**

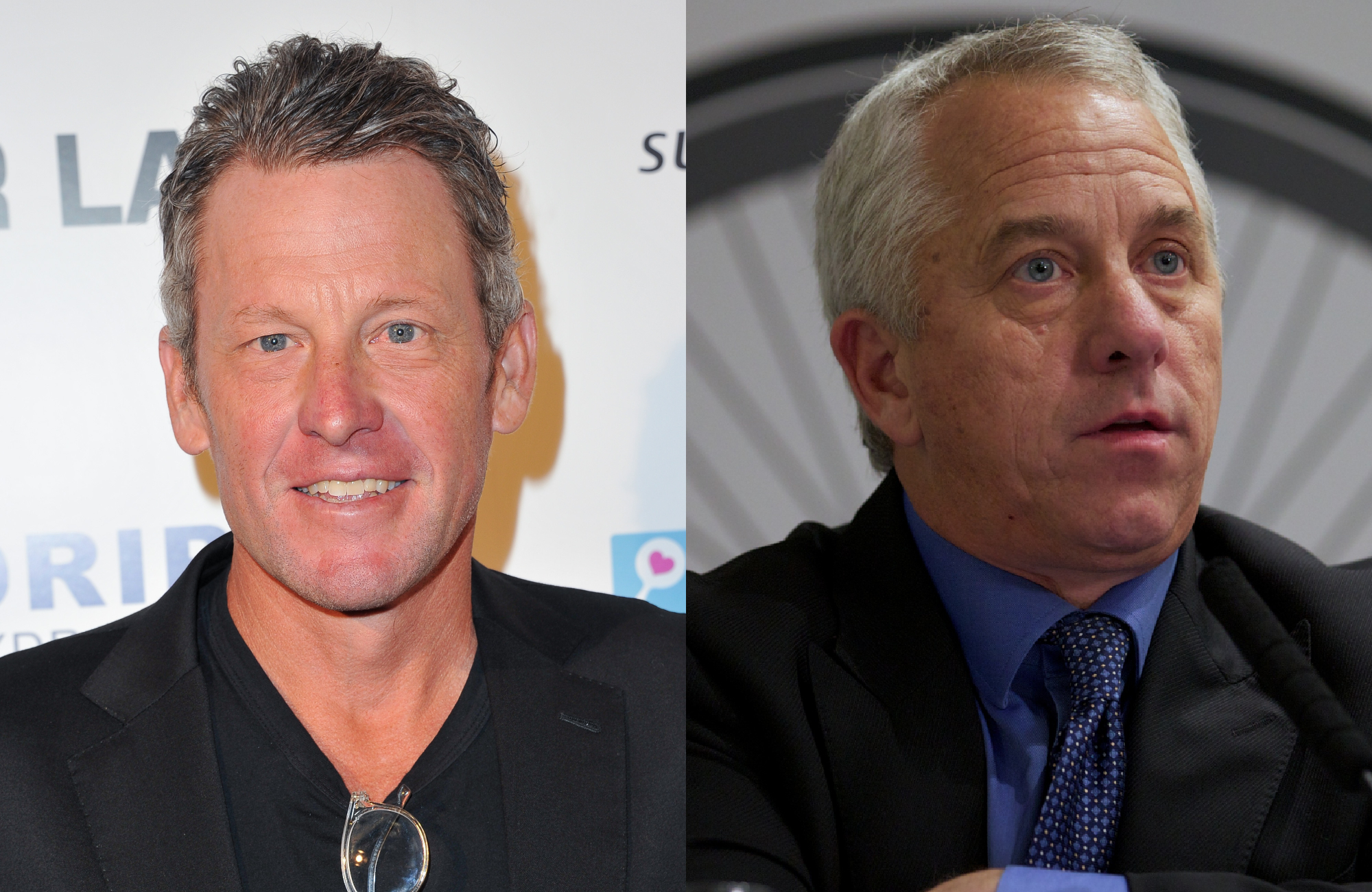

Greg LeMond became the first rider to win the Tour de France without taking a stage victory since Lucian Aimar in 1966. Some cited that as evidence of the negative riding Fignon talked about but that is to ignore the reality of the race that unfolded. For three weeks, he was racing to catch up with someone who had been allowed a ten-minute lead.

Breukink won the Lac-de-Vassivière time trial to take third place. “Maybe I could have won but the big break changed everything in the race. Instead of racing against LeMond and Delgado and the others, we were always calculating how to catch them, first Pensec, then Chiappucci. It changed the race and it’s impossible to say what would have happened if it had been more normal. It’s annoying to finish third when I was the second best in the Tour. We gave Chiappucci a present of 10 minutes. That’s what it was, a present.”

**

TOUR DE FRANCE 1990 OVERALL STANDINGS

1. Greg LeMond (USA) Z in 90hr 43min 20sec

2. Claudio Chiappucci (Ita) Carrera Jeans at 2-16

3. Erik Breukink (Ned) PDM at 2-29

4. Pedro Delgado (Spa) Banesto at 5-01

5. Marino Lejaretta (Spa) ONCE at 5-03

6. Eduardo Chozas (Spa) ONCE at 9-14

7. Gianni Bugno (Ita) Chateau D'Ax at 9-39

8. Raul Alcala (Mex) PDM at 11-14

9. Claude Criquielion (Bel) Lotto at 12-04

10. Miguel Indurain (Spa) Banesto at 12-47

GREG LEMOND TALKS

Cycle Sport: What’s your memory of the 1990 Tour?

Greg LeMond: 1990 was the most satisfying of my Tour wins. 1989 was exciting, 1986 was hard emotionally, but 1990 was the one I enjoyed the most. It was the first time I’d ridden with a proper team around me — in 1986 my team mostly rode against me and in 1989 my team was very weak.

How was your form coming into the race?

I wasn’t on top form, but I was confident. If Fignon had been on form, or if I’d been racing against myself from 1989, it would have been difficult. But it was a strange Tour — it was won on tactics, and I didn’t have to be at 100 per cent.

You used a very unusual set of handlebars in the prologue and time trial, and came second.

We did aero tests on them and they were faster, theoretically. But you’ve still got to apply power to the pedals, and it changed my position too much.

Then you lost 10 minutes the next morning.

Yeah. It was fine, but the only surprise was that Chiappucci was much better than we had expected. We calculated that he would lose that time, so with Pensec in the break, we were happy for it to go. The team time trial threw the race into cat-and-mouse mode — no team wanted to commit. We did think that Pensec was equal to everybody else in the group, so the pressure was off.

Were you joint leaders?

Yeah. No. It was weird — I’d had bad form, so the team lost a little confidence in me early in the season. It was logical for Ronan to be joint leader. The thought process changed — maybe we could win the Tour with Ronan. But I didn’t believe that would be the case.

In the time trial, you lost time to Alcala and barely gained anything on Pensec — was that a surprise?

When I finished that TT I wasn’t even fatigued. I couldn’t get comfortable. It was the last time I used those bars. My elbows were where my thighs should have been, and I was right on the tip of the saddle.

The first two mountain stages, you didn’t gain much time on Pensec or Chiappucci.

I wasn’t sure of my physical ability, didn’t trust my body. I was still thinking of the overall win, but on the first mountain stage, historically, that’s not where the difference used to be made. It wasn’t hard, plus there was caution on my part.

I wasn’t sure where Ronan was on the Alpe, and I was still racing conservatively. It was just like 1986 — you can’t attack when your team-mate is in yellow. I felt good on the Alpe, but I remembered blowing up there in 1989.

I’d actually crashed before the Glandon, hit a pothole, veered off and hit an 80-year-old woman. I thought she was dead, but her husband told me to get going. I’d dislocated my finger — I popped it back in again.

Pensec lost a lot of time in the Villard time trial, but Chiappucci didn’t. How did that change your strategy?

That opened the door for me to be aggressive. The day before, Ronan was doing well, and we thought, maybe he can do it. Then, suddenly, the mood switched — I had to start racing. There was a gap to Chiappucci [7-27] and I had to take that time back between then and the finish.

Did you target the St Etienne stage to get time back, or was it opportunism?

The stage was hot, hilly, windy, which I liked. Chiappucci was just following me all day. There had been an attack, his team had chased. I attacked with Breukink, and all I remember is feeling really strong. It was one of those moments you have to make a decision, and I remember Chiappucci was glued to the road.

But it was the stage to Luz-Ardiden that won you the Tour.

Chiappucci attacked early, and I just watched him go. Winning races takes patience and tactics, and to attack you have to have a certain amount of gas in the tank — he’d spend all day in the wind, working. The same thing happened to Hinault in 1986. But

I knew it would come to the Tourmalet and Luz-Ardiden. When he went away, it was awfully early.

It regrouped at Luz-Ardiden. I remember Parra attacking, going after him, and saw Chiappucci wasn’t responding. From then on, my mindset was to take as much time as I could. I felt strong, and I dropped a lot of people that day.

The next day, my team was exhausted. I flatted near the top of the Marie Blanque, Chiappucci saw, and screamed at his team-mates to ride. My car wasn’t there, I had no wheel; I was so pissed. We pulled two riders back from the lead group, including Duclos-Lassalle, who sacrificed a chance of a stage win in his home town. Chiappucci’s attack was unethical, but I was more angry that the car was not with me.

You’d virtually won the Tour by the end of the Pyrenees. Were you confident for the time trial?

I got so nervous I couldn’t sleep for four days. It was only once I’d ridden the time trial, I realised I hadn’t thought of winning stages.

It was such a strange Tour. We were concentrating on taking time back all the way round. Luz-Ardiden was my highlight — Indurain beat me there, but that’s where I could have won a stage.

CYCLE SPORT'S EYEWITNESSES

Erik Breukink

Third overall

Dutch Grand Tour specialist who also achieve second and third places at the Giro. Faded in the early 1990s. Now a team manager for Rabobank

Claudio Chiappucci

Second overall

Attacking climber who finished on the podium of the Tour three times without winning. Also finished on the Giro podium three times without winning. Now dabbles in Italian reality TV, does publicity work and holds training camps.

Steve Bauer

Yellow jersey, stages 1-9

Canadian all-rounder who’d come fourth in the 1988 Tour, and second in Paris-Roubaix in 1990. Now manages the Canadian Spidertech cycling team, and runs a bike tours company.

Frans Maassen

Winner, stage one

Dutch Classics specialist, winner of Amstel Gold in 1991, also achieved podium places at the Tour of Flanders and Milan-San Remo. Now a team manager for Rabobank

Ronan Pensec

Yellow jersey, stages 10-11, 20th overall

Popular Breton rider, sixth in the 1987 Tour and seventh in 1988, but never matched these results later in his career. Now runs a cycling travel company: www.ronanpensectravel.com

Pedro Delgado

Fourth overall

Spanish rider who won the Tour in 1988 and came third behind LeMond and Fignon in 1989. Also won the Vuelta in 1985 and 1989. Now works as a commentator for Spanish television.

Greg LeMond

Winner

Three-time winner of the Tour de France, and the first American to do so. Now a businessman, with projects including fitness equipment.

This article first appeared in Cycle Sport magazine.

Follow Cycle Sport Twitter: www.twitter.com/cyclesportmag

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.

-

'I'll take a top 10, that's alright in the end' - Fred Wright finishes best of British at Paris-Roubaix

'I'll take a top 10, that's alright in the end' - Fred Wright finishes best of British at Paris-RoubaixBahrain-Victorious rider came back from a mechanical on the Arenberg to place ninth

By Adam Becket Published

-

'This is the furthest ride I've actually ever done' - Matthew Brennan lights up Paris-Roubaix at 19 years old

'This is the furthest ride I've actually ever done' - Matthew Brennan lights up Paris-Roubaix at 19 years oldThe day's youngest rider reflects on 'killer' Monument debut

By Tom Davidson Published

-

Greg LeMond becomes first cyclist to receive Congressional Gold Medal

Greg LeMond becomes first cyclist to receive Congressional Gold MedalLeMond becomes only the 10th athlete to win the highest civilian award in the USA

By Jonny Long Published

-

Lance Armstrong says he didn't like the Greg LeMond part of the ESPN documentary

Lance Armstrong says he didn't like the Greg LeMond part of the ESPN documentary'There are still very specific things that I think still upset him,' said the film's director

By Jonny Long Published

-

Five times the Pyrenees blew the Tour de France wide open

Five times the Pyrenees blew the Tour de France wide openThe Tour de France can be won and lost in the Pyrenees, so take a look at some of the iconic moments in recent Tour history in the mountain range

By Stuart Clarke Published

-

Greg LeMond: The Giro was like a training ride in my day

Greg LeMond: The Giro was like a training ride in my dayThree-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond backs Alberto Contador's Giro-Tour double, but says it will be harder than when he rode them in the eighties.

By Stuart Clarke Published

-

LeMond: Quintana will be Froome's biggest Tour de France rival

LeMond: Quintana will be Froome's biggest Tour de France rivalThree-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond is backing Chris Froome to win the Tour de France, but insists Nairo Quintana will give him a run for his money

By Stuart Clarke Published

-

Laurent Fignon: A tribute to an icon

French cycling lost one of its most enigmatic figures earlier this year, when two-time Tour de France champion Laurent Fignon died. Here is our tribute to a man who stood apart from the crowd.

By Edward Pickering Published

-

Classic Races: Tour de France 1990

Classic Races: Tour de France 1990An early escape turned the 1990 Tour into a three-week game of catch-up for reigning champ Greg LeMond. Would he recapture last year’s triumph or had he left it too late?

By Cycle Sport Published

-

Greg Lemond Interview: Tour de France 1990

Greg Lemond Interview: Tour de France 1990Cycle Sport talks to Greg LeMond about his 1990 Tour de France win

By Cycle Sport Published