In-depth: How Ukraine's cycling scene is surviving the war and even helping the effort

Cycling Weekly finds out how the sport in Ukraine has lost stars but continues to inspire and even form part of the war effort

Oleksandr Onoshko was a cycling celebrity in the southern Ukrainian city of Odessa. A former professional who had raced across Europe, his career highlight was winning a stage of the Tour of Turkey in 2005.

“Everyone knew Oleksandr,” says sports photographer and amateur racer Lurii Makalis. “He was a kind man, a real professional.”

His adopted city of Odessa was one of Ukraine’s cycling heartlands, with two professional teams, seven amateur clubs, and a local cafe that was colloquially known as the cyclist’s hub. It was a city that breathed bike racing.

After Onoshko retired, he set up a coaching business in Odessa. He then moved back to his home city of Mariupol in eastern Ukraine and was head coach of the club he had co-founded, Atlelic Cycling Club. His aim was to develop cycling in the city and introduce more children to the sport. He told everyone he met of his enthusiasm.

“He thought 2022 would be a great year for the cycling community in Mariupol,” says his friend Makalis. “It was post-Covid, he could race across Ukraine and Europe again, and he was setting up his own club to help youngsters, which was his passion.”

When Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February, it wasn’t long before Mariupol came under sustained attack from the invaders.

“The Russians forced all of Oleksandr’s young riders to flee to other parts of Ukraine and to Europe, but Oleksandr stayed behind,” explains Makalis.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In March, just a few weeks into the war, Onoshko was killed by Russian shelling in his now-devastated and occupied city. Speaking to me via Telegram – the preferred app for Ukrainians – Makalis reveals he didn’t find out until May.

“It was the third month of the war when a man confirmed to me that Oleksandr was dead.”

He takes a gulp to steady his voice. “There was no internet there so we had no idea.” Onoshko was 40 years old.

Green shoots

Since the outbreak of the war, the cycling scene within the country has been decimated. Races are mostly banned because emergency services are required at battlefields, while cyclists in or close to the conflict zones dare not cycle too far for fear of triggering landmines.

Ukrainian cycling, according to 2019 men’s national champion Andriy Kulyk, “doesn’t exist anymore”.

But remarkably, if you look hard enough, there are green shoots of racing in some communities and steely commitment to rebuild what was once a thriving scene when the war is over.

Over the last year, however, they have mostly put their bikes and their bodies into the service of their country’s defence. With that inevitably comes many more tragedies like Onoshko’s.

Back in Onoshko’s former home of Odessa, Palmyra Cycling Team’s amateur rider Sergiy Kalchenko was known for his wide smile.

“He wasn’t the strongest, he’d be the middle of the pack, but he always said that his aim was not to win but to enjoy racing his bike,” says photographer Makalis.

Last August, Kalchenko drove to Mykolaiv, the strategically important city in southern Ukraine, with some friends to deliver food and water. It was while volunteering that he was fatally struck by a Russian rocket.

“It’s horrible,” Makalis says. “He was just trying to do a good thing and he was killed. I’ll never meet these people again and that’s hard to live with.” Kalchenko was 39.

Ukrainian cycling’s losses during the past 12 months are not limited to Onoshko and Kalchenko. Just a week into the war, the esteemed coach and former professional Oleksandr Kulyk was killed in an attack while helping rescue people from his home city of Sumy in the north, which was coming under a barrage of Russian artillery.

He had been credited with the development of a number of successful Ukrainian cyclists in the past three decades and was the father of Andriy Kulyk. Andriy was out on a training ride at the time and did not learn of his father’s death until after the news was broken to the Ukrainian Cycling Federation. Oleksandr was 65.

The death toll from the ongoing war continues to rise. Since the full-scale invasion a year ago, an estimated 200,000 Ukrainian and Russian military personnel have been killed, while around 10,000 civilians have lost their lives.

Another cyclist among the dead is Maxim Semenov. He was the pillar of the cycling community in the industrial city of Dnipro – the president of its cycling association, a racer himself, and an organiser of hundreds of competitions. He fought passionately to develop the sport within the region.

In early May, a few days after his birthday, Semenov was shot dead in a battle with the invading Russian army. A statement from the Dnipro Association of Cyclists communicated that an entire community had lost a “brother and a leader”, and continued: “Max’s death is an incredible pain and a tough loss for us all. We’ll never be able to ride wheel to wheel with him again.” Semenov was in his early-40s.

Cafe life

Makalis, a recent winner of the Mark Gunter Photographer of the Year Awards, speaks fondly of Odessa. A contact had informed me that the historic city had a thriving racing scene, and the Southern Cycling League had put me in touch with Makalis due to his English fluency.

“Odessa is the capital of cycling in southern Ukraine,” he tells me proudly. “Cycling is popular and people promote it within society.”

Since 1995, the city has hosted numerous UCI races, including the Odessa GP. The Southern Cycling League, meanwhile, held between 12 and 15 separate races each year pre-invasion.

“There was a full calendar of events,” Makalis says. In pre-war Odessa, the Tour de France Cafe was the go-to place for the coastal city’s sizeable cycling scene. “Before the war people would come in and watch the Tour or Paris-Roubaix on the big screens,” Makalis remembers.

“There’d be head-to-head Zwift races too. It was the place for cyclists.”

The cobbled Classics, however, were not what brought people into the cafe last spring. Instead, it became a collection point for items that would be sent to the frontline and for those escaping their war-torn homes.

Among the donations were dozens of inner tubes and bike tyres that were used as makeshift tourniquets when first aid stocks ran low.

“When people in the army were saying they didn’t have tourniquets, people rushed to the Tour de France Cafe with new and old bike tyres,” Makalis recalls. “We went through so many – you cannot believe how many inner tubes and bike tyres saved lives. It was unbelievable.”

So far Odessa has avoided Russian occupation, but it’s been shelled and struck by missiles and the blackouts, sometimes lasting all day, have plagued the city since October.

Just like in much of the rest of the country, races are prohibited, but Sunday club rides have continued and last summer several clubs arranged informal TTs of around 20km.

“I’ve never seen so many people so happy to be riding their bike,” smiles Makalis. “Just to see friends safely and uninjured, it was pure joy. Riding and chatting alongside our friends made us all appreciate every second on the bike because we are aware that it can all change in the near future.”

Call to arms

Many cyclists, amateur and professionals, have left behind their families to fight. Ukrainian former pro Yaroslav Popovych, a Tour de France stage winner and a current DS at Trek-Segafredo, knows of up to 20 cycling colleagues on the frontline.

“A friend of mine who I first raced with when we were 12 is fighting,” he says. “Guys who own bike shops and high-level amateur racers are also there. I know of two coaches and a DS who have died.”

When the war began, Popovych made headlines for making six trips from Italy to deliver clothes, sleeping bags, food and medicine. At the time he spoke about joining the fight, only for friends to dissuade him owing to his lack of military experience.

Would he change his mind if Russia were to launch its expected new offensive?

“I often think about this situation and I am prepared,” he tells me just a few days before he visits the frontline for the first time. “I have a backpack at my father’s house ready with a bullet-proof vest. If in the next few months it escalates and the Russians come, as they say they will, I will go.”

Popovych was born in the Lviv Oblast, a relatively safe region in comparison to other Ukrainian settlements due to its close proximity to Poland. Restrictions around organising races are less strict in the area, and a decent number have taken place. Yet even here war casts its long shadow over the racers.

“One of my friends who organised one race said that they began at 9am but a few minutes later they had to stop as there were missile attacks 80km away,” Popovych says. “The air raid sirens went off so they had to stop the racing. Three hours later they resumed.”

Ukraine cycling on the international stage

Over the past 12 months, the Ukrainian Cycling Federation has supported around 260 of its athletes across various disciplines and age groups, with most having relocated to European countries.

Internal politics, however, is threatening to disrupt the support, with the country’s Ministry of Sport wanting the athletes to return to Ukraine and for races to be held in the country. This has set the government on a collision course with the federation, headed by former pro Andriy Grivko.

“I understand the request but we have a different mentality: for us, the safety and security of our people is most important, and in the current climate nowhere is safe in Ukraine,” Grivko says.

“We have set up the Ukraine Cycling Academy to provide some races and to give these athletes a chance to find a pro team.”

Also irking Grivko is the way the Ministry of Sport, which funds the federation to the tune of around €1m (£890,000) a year, operates.

“We have a Soviet system, one that only communist societies like China, Russia and Belarus use,” he says. “Each year we have a programme, a vision, good riders, but we don’t have the power to provide it. The Ministry doesn’t provide a budget or information and it decides to spend the money in a different way. They will pay for us to go to European and World Championships, but they give us the money so late that hotels and flights are already booked.”

The Ukrainian Track National Championships were held in Newport, Wales, in November.

Kyiv velodrome's pre-war development

Track ambitions

When the Russians were on the outskirts of Kyiv in February and March, the capital city’s 109-year-old velodrome – reopened in 2017 after a closure of 13 years – prepared to defend its base. “On February 24 we went down to the velodrome and installed barricades and blockages,” the velodrome’s CEO Volodymyr Melnyk tells me over the phone. “We agreed that if they destroyed it, we’d rebuild it again.”

With Russian troops ravaging satellite towns and indiscriminately killing civilians on the outskirts of Kyiv, Melnyk and around 50 cyclists from the capital delivered medicine to people on bikes. “This was the main social initiative of the velodrome and it was a lifeline for so many people,” Melnyk says.

Six weeks later, the Russians retreated. At the end of May, the velodrome began to organise training sessions but noticed a sharp drop-off in the number of attendees. “80% of our kids had left Ukraine,” sighs Melnyk, speaking from the velodrome.

“Between 2017 and 2021 we worked so hard to develop cycling in Kyiv, focusing particularly on 12 to 14-year-olds, and we were in a really strong position. We had kids who were competing for the national team with big prospects.

“Now there is no way that they will grow up as professional cyclists, and they won’t be as fast and as powerful as they were before the war. We now want to grow the next generation, but we are starting from zero.”

As the war enters its second year, fighting continues to intensify, with cyclists protecting their country from the trenches, while others assist the war effort in myriad other ways. The cycling scene, like so many other communities, has been devastated, but not entirely destroyed and one day it will rise again, for they are united in hope and determination.

“We’ll create a new Ukrainian cycling generation,” insists Melnyk, as he looks out over the open-air track. “Our dream is that the Kyiv GP track meeting will return in August as a UCI track event and be a celebration of the end of the war. A lot of sporting glory will return to our velodrome.”

“We realise the price we are paying for this,” concludes photographer Makalis. “We are aware that some cyclists will not be alive at the end of the war, but we know what we are fighting for. When this is over, we’ll organise these races and events again, and they’ll be better than ever. We will continue fighting.”

This article was first published in Cycling Weekly magazine, February 23, 2023

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

A freelance sports journalist and podcaster, you'll mostly find Chris's byline attached to news scoops, profile interviews and long reads across a variety of different publications. He has been writing regularly for Cycling Weekly since 2013. In 2024 he released a seven-part podcast documentary, Ghost in the Machine, about motor doping in cycling.

Previously a ski, hiking and cycling guide in the Canadian Rockies and Spanish Pyrenees, he almost certainly holds the record for the most number of interviews conducted from snowy mountains. He lives in Valencia, Spain.

-

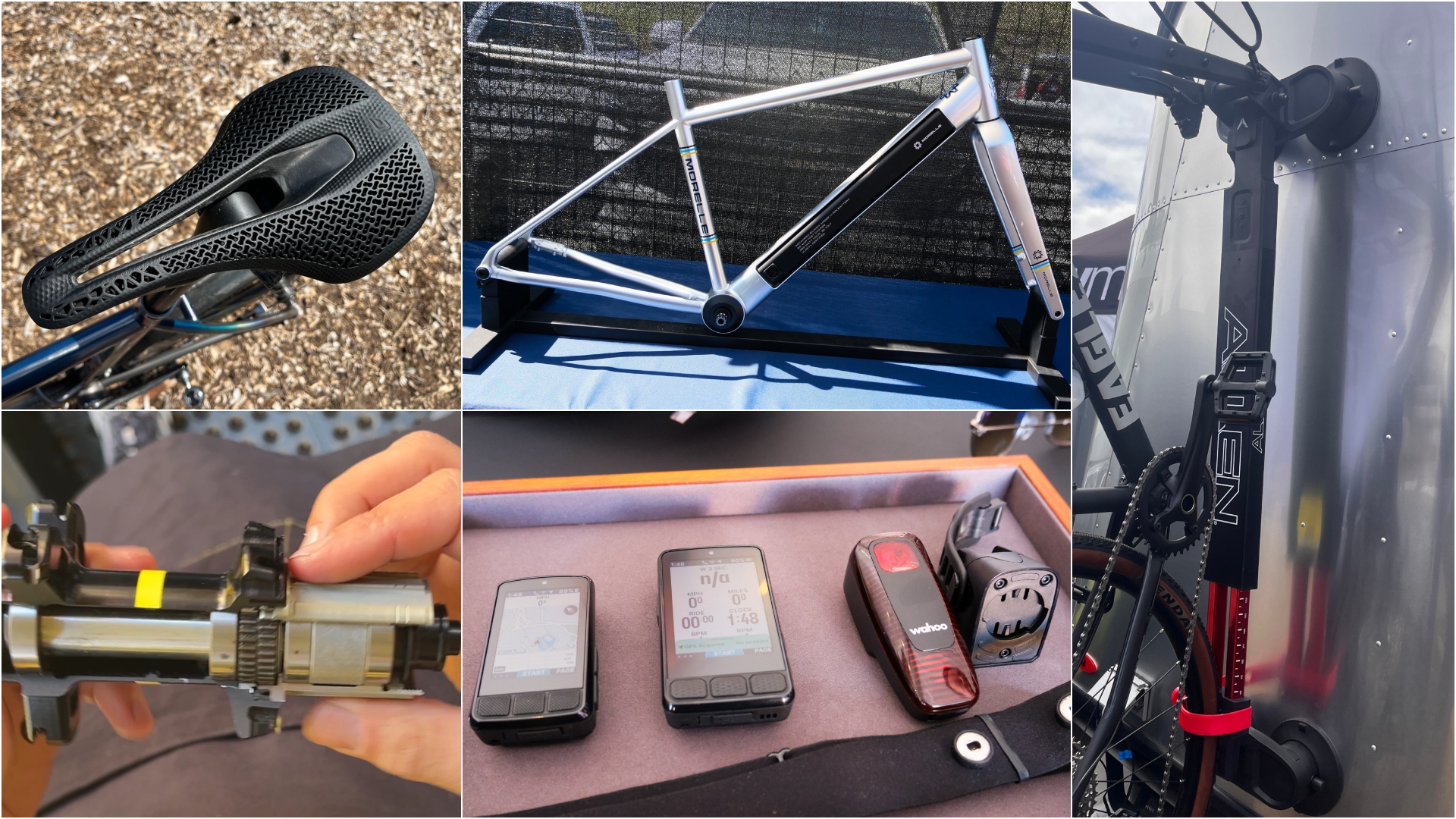

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2A few standout pieces of gear from North America's biggest bike gathering

By Anne-Marije Rook

-

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incident

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incidentCycling's authorities must do everything within their power to prevent spectators from assaulting riders

By Tom Thewlis