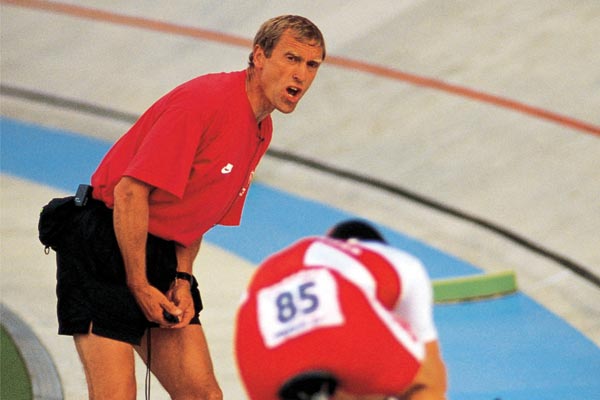

Doug Dailey: The original marginal gain

Great Britain is the best cycling nation on planet Earth. How the hell did that happen? How did Britain emerge from the shadows in little more than a decade?

There are several reasons. Lottery funding turned the key - it now stands at £26m. Then, along came Sky sponsorship in 2008, with £20m in backing to underpin the bid to win the Tour de France. British Cycling gained bolder leaders, smarter physiologists, better technology and reams more data, not to mention raw riding talent and the means to spot it. Compared to 16 years ago... well, there is no comparison.

Doug Dailey has been there throughout but has now retired after 26 years working for BC. From national coach to logistics manager, he has played a key role in the extraordinary rise of the Great Britain team. We couldn't let the moment pass without one final interview with the unsung hero of British Cycling.

CW: So, what does a logistics manager do?

DD: [Logistics] involves the transport, housing and feeding of troops. In cycling terms, it's arranging travel and accommodation and meal plans for riders and support staff, with the added responsibility of entry formalities, accreditation and, in some cases, entry visas.

For an Olympic Games, the team comprises two-dozen riders, at least as many officials, plus equipment and provisions. How does this compare to when you were riding?

DD: It's a lot different from when I went to the Olympics. Each rider can now have as many as three or four bikes. Back in the late Eighties, when I was first appointed as national coach, it was one bike per rider and a support staff comprising manager, mechanic, masseur, full stop.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Moving the team, staff, vehicles and equipment by air must be a major new challenge, and expensive?

DD: When I was racing, if you raced in Europe, that was as far you ever went. But now [cycling] is very much a worldwide sport. With the introduction of the World Cup series, and more disciplines, you can now be racing anywhere in the world. The Track World Cup series, for example, can involve series in South America, Australia, Asia and Eastern Europe, all in one season.

How much has the addition of winter races and championships increased the logistical burden?

DD: You just get the road World Championships out of the way and lo and behold, within a few weeks, you are into the first round of the Track World Cup. [For] the road Worlds, you need to make your accommodation arrangements as soon as the venue is announced, which is at least two years before. For an Olympic Games, your planning starts at least four years out. And now, of course - and I've not experienced this - you've got a team time trial back in the World Championships. That's a heck of lot of beds you've got to find.

What training and skills are needed to become a British Cycling logistics manager?

DD: I actually gained all of my experience in organising travel and accommodation during my time as national coach. My job title was national coach, but actually I had very little opportunity for coaching. Most of the time was spent making race arrangements and managing.

I believe it was easier for British Cycling to secure exchequer funding for a national coach position than it would have been for a team manager/administrator. But calling me national coach gave me all sorts of problems and stress due to the underperforming of national teams in the late Eighties. [His situation became more bearable after Chris Boardman won the Olympic pursuit title in 1992. And on reflection, he reckons he should have quit straight after Barcelona (1992 Olympics) when he was ahead - Ed]

Nonetheless, you carried on after Chris Boardman won the Olympic pursuit title in Barcelona in 1992?

DD: I decided to give it four more years and ended up completely exhausted by the Atlanta 1996 Games. The job should have carried a health warning!

But you were invited back as logistics manager by new performance director Peter Keen - why did you accept?

DD: I have to admit I was more comfortable as logistics manager than I ever was as national coach! Mind you, I didn't expect to be working for British Cycling for 13 [more] years and four Olympic Games! I just thought it would give me a few more years of work. I actually put in the same stint as logistics manager as I did as national coach.

Since 2000, British cyclists have won a staggering 227 world and Olympic medals - including 47 Olympic golds. Quite simply, how?

DD: It shows what you get for your [Lottery funding] investment. There were some barren years before that.

Let's go back to the Sydney Olympics in 2000, where Jason Queally won gold in the kilo and Bradley Wiggins won his first Olympic medal, bronze in the team pursuit. How special were those achievements?

DD: What was interesting, Queally was more probably a direct product of the provision of the Manchester velodrome. He'd been involved with water polo before cycling. When he was first drawn to my attention, he was riding in the B class, not the A class. He was a big, powerful lad, riding very, very well in the bunch. And was quite clearly something of a natural talent.

He was invited onto the national squad because the power was obvious to see. And we had this new facility at Manchester; we were looking to recruit big, powerful track riders and he fitted the bill. I don't think anyone officially steered him towards the kilometre. I think he recognised it as an event well within his scope. And Queally had a single-minded, totally focused approach. I had not seen this before in a sprint athlete. This guy, he recognised an event which suited his talents. And he said, I'm going for it. And he landed it, didn't he?

Lottery funding was announced in 1996, after the Atlanta Games that year. British Cycling received £3m for elite athletes preparing for Sydney 2000. The new velodrome had been open for two years. How soon did you notice the effects of these developments?

DD: We had the Manchester facility for six years and the funding and specialist coaching staff four years [before Sydney]. At one time, we had a national coach. Now we have sprint coaches, endurance coaches, conditioning coaches. So, for all concerned, the Sydney result was quite a quick return. I thought it would take us longer than four years to reap the rewards from the investment.

At the Athens Games in 2004, Hoy won the kilo and Wiggins the individual pursuit, as well as silver in the team pursuit and a bronze in the Madison - with Rob Hayles. Something was clearly starting to work?

DD: Athens was a distinct, real improvement on Sydney, but it wasn't anything like Beijing or London [would be]. Wiggins was actually the star of the team. Three medals. He was down to carry the flag at the closing ceremony, [but] he was trumped at the last minute by Kelly Holmes. He might not have known that. He went home, you see. They were going to fly him back. They don't hang around, these guys. Wiggo got gold, silver and bronze. Quite something, that.

I was the admin manager on the team. We were pretty familiar with Athens... [from] attending World Cups there. When we were there, it was an outdoor facility. And for the Athens Games, it was an engineering wonder. They actually built a roof beside the track, which they moved over the track on rails. How the hell they did it, I don't know.

By 2004, Peter Keen had been headhunted by UK Sport, and Dave Brailsford became the new world-class performance director for cycling. Was there a noticeable change in the way things were done?

DD: There was no immediate difference. [Brailsford] had a unique approach, different to Peter Keen. But he didn't come and ring the changes immediately. I think he took stock of the situation and then made his mark as he built up an experience and came to grips with the demands of the various Olympic disciplines.

Brailsford's approach came from working with Steve Peters, the sports psychologist, a strong advocate of the ‘kings and queens' concept [which suggests] the rider eventually assumes control over their own programme. You know - Wiggins is in control of Wiggins, Victoria Pendleton is in control of Victoria Pendleton, Chris Hoy is the boss of Chris Hoy. They have to move to this position; they don't become kings and queens overnight. You've got to have proved your worth. It doesn't happen in all sports. In some, you do exactly as you are told.

At the Beijing Olympics in 2008, Nicole Cooke won gold in the women's road race, Hoy won three golds, and the British team won 14 medals, plus 20 for the Paralympics. British Cycling was flying high - how did that feel?

DD: If a sport gets 14 medals, quite clearly they're worth having a look at. It was an amazing achievement. We were stunned by it. We were winning two medals a day. It was amazing. We were wondering, where is it all going to end?

Shanaze Reade should have delivered as well [in BMX; she crashed] and if Liam Killeen hadn't fallen on the first corner in the mountain bike...

How special was Hoy's performance?

DD: Quite clearly, he targeted those three medals. Team Hoy plan ahead, that's Hoy with his coaches - each athlete has their own support team. Team Hoy planned to win those three gold medals. They knew where Chris was at.

It was quite clear, from the athletic point of view and given the length time he's been in the sport, his rate of development, that he was at peak powers in Beijing. You don't win three golds unless you are absolutely... It was realised by Chris and his support team and they went for it.

And it was a case of getting the training right and the peaking right, and then holding that form for the duration of the Games. Not easy. But he had the form of his life. Once you've got that form and you get off to a good start... The whole team got off to a great start with Nicole Cooke winning gold in the women's road race.

At the London Games, there was disappointment when the British team missed out on a medal in the men's road race - but that was forgotten by the on Sunday, when Lizzie Armitstead landed Team GB's first medal of the Games, silver in the road race. And when Wiggins surpassed himself to win gold in the men's time trial and Chris Froome took bronze, Britain was off to an even better start than in Beijing. That threw a switch, didn't it?

DD: Well, I'm sure Steve Peters could explain the psychology behind it.

Talking of psychology, tell us about the ups and downs riders will experience, comparing one Games to another. Between Beijing and London Games, for instance?

DD: Well, they do have peaks and troughs. The experienced, quality athlete and their coaches can smooth these out so the troughs aren't too low. They still maintain those peaks.

Between Beijing and London, we had a few troughs and had to settle for silvers and bronzes [in the Worlds and World Cup], so a shallow trough... I mean, Hoy wasn't going so quite so well pre-London as he was pre-Beijing, and Victoria Pendleton definitely wasn't. But athletes of this calibre aren't quite so excited by World Cups any more. Olympic Games... that becomes the norm.

We have set a standard since Beijing, which is at a very high level. That is now the norm. That is our normal way of operating at that level of performance. They will often have a few self-doubts about an Olympic Games. They are all human. But they certainly deliver on the big occasion.

The coaches have a terrific amount of experience and can reassure athletes and show them where they were 12 months ago or 24 months ago, and show them they are on the right pathway. We have so much data now.

We knew London was the next Games after Beijing. We also knew we had won 14 medals. As a sport, you must think, ‘My goodness, have we peaked a bit early? There's no way we are going to get 14 medals in London!' Especially when the UCI - rightly or wrongly - had moved the goalposts so much. The UCI considered it was not in the best interests of the sport for one nation to be so dominant in an Olympic competition. So they changed the rules.

Yes, for Beijing, the UCI removed the men's and women's individual pursuit, the men's and women's points race, and the men's Madison. What did you make of those changes?

DD: They brought in the one-rider-per-event rule, so it was quite easy then to see what impact this would have. Look at the times we multi-medalled in Beijing. It was going to cost us three of four medals straight off.

Did Brailsford attempt to take the heat out by saying we couldn't expect to do better than in Beijing, all the while working towards trying doing just that?

DD: Yes, Dave was rising to the challenge. We were looking at seven or eight medals [in London], and if we got into double figures we'd be [doing well]... and we ended up with 12. We outperformed our best estimate. In fact, I think if you compare London to Beijing, the 12 in London was possibly better result because it was across more athletes and more events.

In 2008, Nicole Cooke completed that marvellous double - national and world road race titles, followed by Olympic gold in the road race in Beijing. What did you make of that career pinnacle?

DD: Given the distractions involved after winning Olympic road gold, it is quite difficult to win gold straight after an Olympic Games. You've got to hand it to both Nicole and Victoria Pendleton - Victoria won the world sprint title straight after becoming Olympic champion in 2008. It's not an easy thing to do; I know the demands on the time of Olympic medallists are massive. You have to take your hat off to them.

How has British Cycling managed to come so far in such a short space of time?

DD: Well, these changes haven't occurred overnight. BC has worked towards this position for many, many years now. This was the ideal we were dreaming about, and once we got the necessary funding, facilities and coaching staff, we were able to home in and make sure we fully understood the demands of each and every discipline. And then go for it.

Dave Brailsford is renowned for his attention to detail. He had this policy of amalgamating or adding together all the various marginal gains. And most of these marginal gains, they are only a per cent here and a per cent there, but when you add them all together, there is a very worthwhile speed advantage. Lots of work goes into the background to evaluate all this.

There's a lot to applaud; there is a lot to be proud of, but I've a feeling that at the end of the day, you can forget all the marginal gains, forget almost everything. It's about the athletes. And what we have now, and this has taken a few years to get to this, we now have a pathway for talent. And for any talented young cycling athlete, there is now a pathway to success.

We now have a proven pathway to go from talented youngster to Olympic champion. [Wiggins] was a very promising junior pursuiter who won a world title and [now] he's not only an Olympic champion but a Tour de France winner... You go from entry-level to talented youngster to Olympic champion.

We are actually seeing current Olympic champions who have come all the way through the system. They are world road champions, [and] a Tour de France winner in Wiggins.

What about Mark Cavendish - who began his racing as a schoolboy on the Isle of Man, brought on by the Scottish Provident circuit racing league in Douglas, run by Dot Tilbury - is he another good example?

DD: Yes. Cavendish came through the system from start to finish. The Isle of Man Cycling Association gave Cav an opportunity to try cycling. He quite clearly enjoyed it and was good at it and he was quickly, because of his results, picked up, nurtured, developed and started off on the track.

At one time the track was the only route in. We had to start somewhere. This came very much from Peter Keen when he was first appointed. You go for what is winnable. Then we had riders who graduated from endurance track, like Bradley Wiggins.

Chris Boardman demonstrated this in the early Nineties. He went from being Olympic pursuit champion to riding as a top pro. He had a couple of TdF yellow jerseys, a real purple patch on the road.

Now if you look at his road career prior to becoming Olympic champion his international road results were pretty thin on the ground. But his talent was recognised because they realised that a guy who can go quickly over four-and-a-half minutes... had something there.

Is there a particular winner who stands out for you above all the others?

DD: Well, they are all precious. I marvel at them all. I've been around long enough to appreciate that anyone who wins a world title or an Olympic title... they are a bit special.

OK, it's difficult now to pick one out because there have been so many of them. If you say to me, what was the highlight of my 13 years as national coach, it was Chris Boardman's gold (1992) and Obree's pursuit world titles, because there weren't that many [medals, at that stage].

When was the turning point, was it Athens 2004?

DD: I actually put it a little bit further back than that, to the Seoul Olympics [1988]. That was definitely a step in the right direction. In Seoul, we had two fourth places: Eddie Alexander as a sprinter and Colin Sturgess as a pursuiter.

How different was the structure back then?

DD: There was no structure or clearly defined development pathway for the talented rider, because there was very little funding... no full-time, specialist coaching staff and, for the track rider, no world-class, indoor facility.

I was the only full-time person working on performance. The national squad was in excess of 100 riders and the vast majority would never be competitive in major competition. To be effective, I should have been working with no more than six or eight riders. I had inherited a way of working that was unlikely to produce results at major championship level.

The Seoul result gave an indication that even with very little in the way of resources, results could be achieved by individual performers. To get a result in Barcelona, all our limited resources needed to be concentrated on one or two riders, who had a measured and proven ability to bridge the gap from domestic champion and Olympic champion.

I count myself very fortunate that two gems came to the fore on my watch: Chris Boardman and Peter Keen. Weeks out from the Barcelona Games, Pete was able to demonstrate Chris was on the pace, [that] a gold medal was a realistic possibility. Chris duly delivered our first Olympic gold cycling medal for 72 years.

Four years later in Atlanta, Chris and Pete almost pulled it off again in the individual time trial, plus the added bonus of a fine bronze for Max Sciandri in the road race.

The lean years that extended from 1976 through to Barcelona looked to be behind us. I was convinced in my own mind that the Olympic Games was the arena for British Cycling for the foreseeable future.

Who is Doug Dailey?

Doug Dailey, now 68, has retained the lean and craggy look, the powerful physique from years of competing. The Merseysider, who now lives in North Wales, was awarded the MBE for services to cycling in 2008, and British Cycling awarded him its highest honour, the Gold Badge.

Dailey enjoyed a successful amateur racing career spanning 26 years and was twice British road race champion, representing GB on many occasions, such as the 1972 Olympic Games and the Tour of Britain Milk Race.

After his retirement in 1986, he was national coach for 10 years and subsequently British Cycling logistics manager and team selector. Dailey's organisation skills were key to making it all work - helping to shape the transformation of our nation's cyclists from also-rans to world-beaters.

The golden years: 2000-2013

Overall, since the dawn of the new millennium, GB riders and Paralympic riders between them have won a staggering 228 Olympic and World Championship medals. That includes 19 Olympic gold medals and 28 Paralympic gold medals.

The four big hitters are Sir Chris Hoy (seven Olympic medals - making him the most successful British Olympian of all time, plus 11 world titles); Bradley Wiggins (four Olympic gold medals, seven Olympic medals, six world titles, Tour de France champion); Victoria Pendleton (two Olympic titles, nine world titles); Mark Cavendish (three world titles (two Madison, world road title), points jersey in the Vuelta and Tour de France, 23 Tour de France stage victories); Sarah Storey (four Paralympic gold medals at London 2012 and two in Beijing).

This information is taken from British Cycling's website which lists all the medallists, from 2000 to 2012.

Sir Chris Hoy on Doug Dailey

"I've got huge respect for Doug, and we always got on very well. He was the only person in the team who was there throughout my whole career - from the first time I represented GB in 1996, right through until the London Olympics last summer.

"His famous catchphrase was ‘bloody hellfire' which everyone in the team tried to do an impression of! He had a great sense of humour and was always really well respected in the team.

"He used to call us ‘sprinter types' and initially [mid-Nineties] he had the impression sprinters didn't train very hard, but once he saw us in action, we earned his respect. But he was always taking the Mickey out of us - even in the last couple of years. I remember before a recent Majorca training camp, he said: ‘Will you be taking your bikes?'"

Rob Hayles on Doug Dailey

"He's a legend. He's been there since the start, as far as my career is concerned. At my first junior World Champs, he was coach, manager, sometime mechanic and soigneur, along with Sandy Gilchrist.

"He was running BC on the racing side for years and he knew everything. There was a point when people said [to him] ‘you can't go'. Nothing was on record; all the contacts were in his head. He knew everyone; wherever he was in the world, he'd always know someone.

"His catchphrase when we were team pursuiting was ‘just nice'. If we lost a rider, he shouted, "There's three of you!". One time when we got it wrong, he shouted "There's f*****g three of you!" But he almost never swore; if he did, you knew it was serious.

"Allegedly he did 100 sit-ups every morning, and he never drank. The one time we got him drunk was at the end of 1991 - we just kept topping his glass up when he wasn't looking."

Brian Cookson on Doug Dailey

"I remember Doug from back in his racing days and being a class apart from most of us back in the 60s and 70s. He wasn't a great climber or sprinter. He won races by being tough; he'd always be at the front after a selection.

"I remember the national road championships in 1972 in Leyland on what was essentially a flat course. He got away with Phil Griffiths and then dropped him in the last mile on a course that a lot of people thought was too easy.

"He was an exceptional national coach. He exceeded what we had hoped to get from the position. We didn't achieve massive success but with the resources he had back then, he got some world class performances, then he worked with Peter Keen to get Chris Boardman gold in 1992. That was mould-breaking and set the standard for what we have now."

This article originally appeared in the February 7 2013 issue of Cycling Weekly magazine

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.

-

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much more

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much moreSupported It's not just Bontrager, Balfe's has a huge selection of discounted kit from the best cycling brands including Trek, Specialized, Giant and Castelli all with big reductions

By Paul Brett

-

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-Liège

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-LiègeUno-X Mobility to rebrand as 7-Eleven for Sunday's Monument to pay tribute to iconic American team from the 1980s

By Tom Thewlis