Five weird ways professional cyclists bent the rules to their favour

From train rides to blood doping, cycling can be an incredibly devious sport, like the ones in the news right now

For once, this week, other sports have taken the lead in reports of nefarious activities, with chess player Hans Niemann being accused of cheating more than he has let on, and boxer Conor Benn testing positive for clomifene.

There have been some lurid suggestions of how Niemann, a 19-year-old American, could cheat at chess, but what we do know is that he allegedly cheated on online chess games, according to a report.

There were wild reports that the chess player used something secreted inside his person to cheat, but that is yet to be proved.

What we do know is that a 72-page document, conducted by Chess.com and initially reviewed by the Wall Street Journal, found that Niemann “likely received illegal assistance in more than 100 online games” as recently as 2020, including in events where prize money was at stake.

Cycling is no stranger to weird ways of bending the rules or outright cheating, and some are very famous, like the Lance Armstrong case or recent allegations of motor doping, but some are less well known and, frankly, even weirder.

A sport that takes place in the open world is ripe for meddling with, as there are lots of areas away from the eyes of commissaires - although live start-to-finish TV broadcasts might have imperilled this.

Of course, cycling has not escaped the whiff of doping, and probably never will thanks to the sheer gains that can be made in such an endurance sport. Just this week, seven Portuguese riders were banned for doping offences, proof (if it was needed) that there is still a dark shadow over the sport.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Here are five slightly more left-field ways that cyclists have tried to gain an advantage over the years. Of course there are many more, but consider this a gateway into cycling's weird cheating.

The one with cramps, corks and cars

The early days of professional cycling were filled with intrigue and, to be honest, blatant cheating. In the first Tour de France, in 1903, one of the favourites for the win, France's Hippolyte Aucouturier, was handed a spiked bottle by a spectator; the ensuing stomach cramps put him out of overall contention.

The next year Aucouturier came back with a plan to trick his way to an easier time, which involved a cork, a length of string, and a car. The Frenchman held a cork between his teeth and was pulled along by a car; the ruse sounds effective if slightly dangerous - riders crash into the back of cars by their own volition, let alone being attached to them.

We're unsure on the level of his dentistry bills.

The one with the train journey

The winner of that first Tour de France, Maurice Garin, came back the next year and was one of a plethora of people disqualified for cheating. There's bending the rules a little bit, and then there is taking a train to skip a bit of the course, something he was alleged to have done.

It is hard to imagine in this age of cameras everywhere, and live TV coverage, but in the 1900s it was, apparently, easy enough to do, just hop on a train and then get off. It is much harder for one of today's peloton in full gear to just pop onto a TGV.

Cyclingnews spoke to someone who knew Garin in 2006. "He was amused by it," Maurice Vernaldé told them. "Not embarrassed, not after all those years, and he used to laugh and say 'Well, I was young…' and admit it. Maybe at the time he said he didn't, but when he got older and it no longer mattered so much…."

The top four of that Tour were eventually disqualified, thanks to a litany of illicit behaviour, with fifth-placed Henri Cornet winning, the youngest person to ever win a Grand Tour.

The one with the condom of urine

Doping and cycling have always gone together, from the early days of alcohol, chloroform and cocaine, through amphetamines and steroids, to the more modern painkillers and EPO.

For decades, these methods were allowed, or tacitly accepted, before doping controls began to be introduced in the 1960s. This meant ways of evading the testers became increasingly creative, ending with the blood bag swapping of the 2000s, and modern micro-dosing.

Before the Lance Armstrong era of team-controlled doping, individuals took it upon themselves to break the rules, often in strange ways.

In the 1970s, there were more blatant ways to avoid testing positive. In 1978, Belgian champion Michel Pollentier was found to be using a condom filled with clean urine to simulate pissing, and thus avoid his contaminated urine being tested. Unfortunately for him, the ruse was discovered while he was attempting it. Who knows how many people got away with this before, however.

The one where you basically hold onto a car

Sticky bottles are commonplace in cycling. For the uninitiated, it's where a rider collected a bottle from a team car gains a brief moment of respite from chasing back on, using the power of the car for a little bit.

They happen all the time, and there is a grey area between what is allowed and what isn't - it usually depends on the time it lasts, the race situation, and also the advantage it imparts. A quick hold on for a second to chat is one thing, but practically receiving a tow is another.

This year, 2021 world champion Elisa Balsamo was disqualified from Paris-Roubaix for a sticky bottle that lasted a little too long.

There have been many more rumours of riders holding onto cars than actual disqualifications, so this is nothing new.

But in a much more egregious example of cheating, Vincenzo Nibali was kicked out of the 2015 Vuelta a España for holding onto his team car for 100m. Just like so many modern examples of rule bending, Nibali was undone by footage of the incident - if it hadn't been on camera, he might have gotten away with it.

The one with a motor in the bike

The last decade has seen a rise in allegations of motor doping in the professional peloton, with little evidence of it actually happening. The idea of having a motor in a bike is a simple one, if slightly ludicrous, and the UCI has introduced testing of bikes at various points during and after races to make sure they conform to the rules.

At the 2016 cyclocross World Championships, however, a motor very much was found in a bike. Belgium's Femke van den Driessche was found to have a motor in her spare bike during the under-23 race, and was subsequently banned for six years.

If there are motors in bikes at under-23 level, you wonder what else is going on, although it would surely be rather tricky to get away with as all the world's cameras are on you.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Adam is Cycling Weekly’s news editor – his greatest love is road racing but as long as he is cycling, he's happy. Before joining CW in 2021 he spent two years writing for Procycling. He's usually out and about on the roads of Bristol and its surrounds.

Before cycling took over his professional life, he covered ecclesiastical matters at the world’s largest Anglican newspaper and politics at Business Insider. Don't ask how that is related to riding bikes.

-

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incident

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incidentCycling's authorities must do everything within their power to prevent spectators from assaulting riders

By Tom Thewlis Published

-

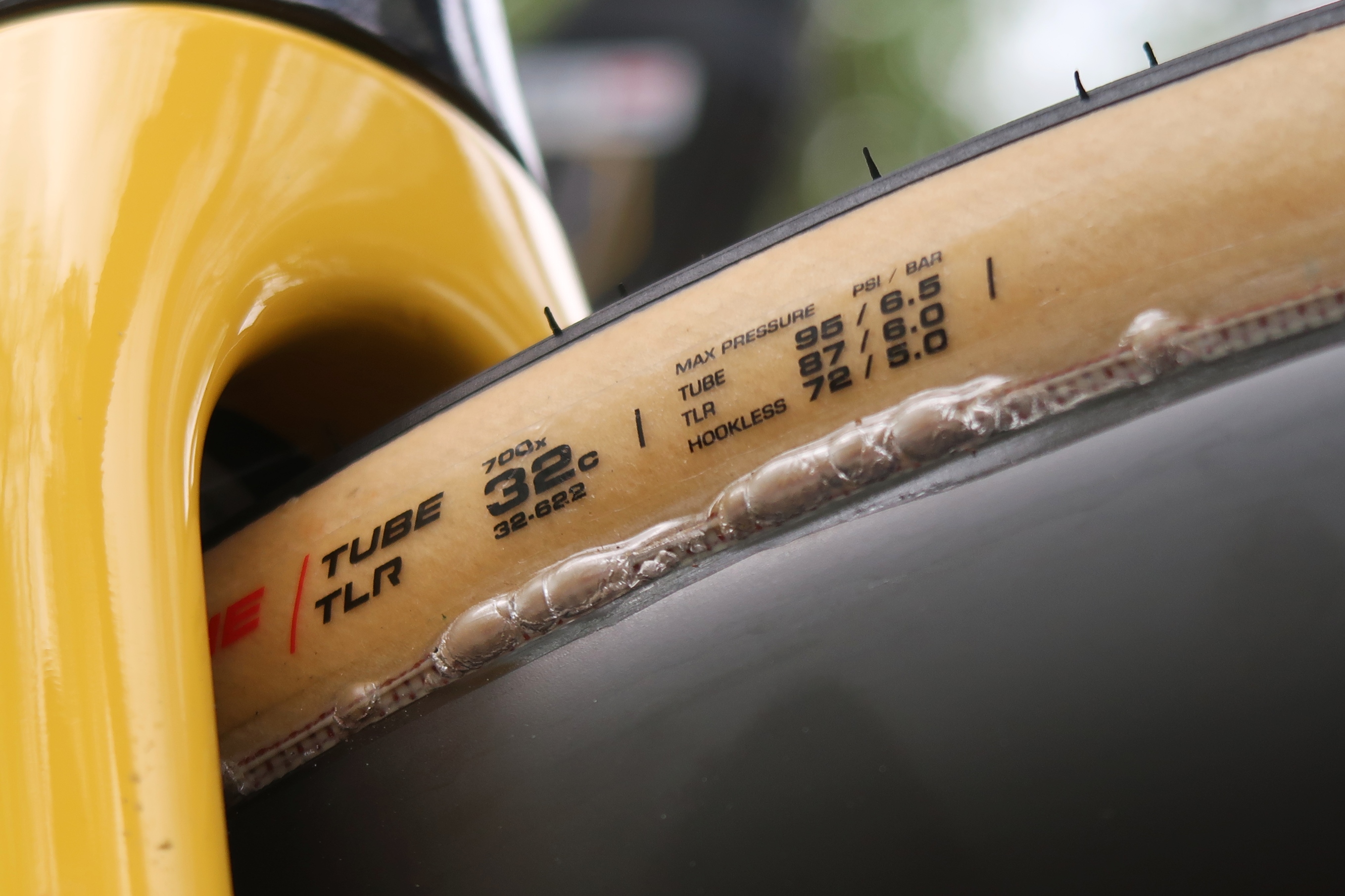

Why Paris-Roubaix 2025 is proof that road bike tyres still have a long way to go

Why Paris-Roubaix 2025 is proof that road bike tyres still have a long way to goParis-Roubaix bike tech could have wide implications for the many - here's why

By Joe Baker Published