From the 'inhumane' to the wacky, six times the rules of cycling have been questioned

For a sport so rooted (some might say stuck) in tradition, cycling can still surprise and baffle when it comes to rules

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Movistar boss Eusebio Unzue raised eyebrows this week when he suggested that teams should be able to substitute riders in Grand Tours. Cycling had become too "inhumane", he told L'Equipe. "The regulations should be humanised. Stop being so harsh."

Unzue speaks with experience, having been involved in team management since its days as Caisse d'Epargne back in 2007. Cycling had become stuck in its ways, he said. It should look to the future and protect the health of its riders.

He gave the example of a rider who has crashed but must still make it to the finish to have any chance of starting the following day.

"To be able to start again the next day, he sometimes has to do 60 or 80 kilometres with a broken wrist," said Unzue. "He can only be examined once he arrives, having suffered like an animal. We really can't humanise this?"

It may be hard to fault the basic theory, but making it work in practice could prove more of an issue. Whether it ever become reality or not, Unzue's left-field / innovative / crazy (delete as appropriate) suggestion would not be the first. How about these five?

1. The Athletes' Hour

'The UCI is at it again'. It has been an oft-repeated mantra over the years, each time the sticklers in Aigle bring out a new appendix to one rule or another. But it was never uttered quite so vehemently as it was in the year 2000 when the UCI swept a casual hand back through the years to wipe out all Hour records as far as Eddy Merckx's 1972 mark.

Records set by Francesco Moser, Graham Obree, Chris Boardman, Tony Rominger and Miguel Indurain were gone in one fell swoop, with the UCI deciding that Obree's tuck and the popular superman position had strayed too far from what cycling should be.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

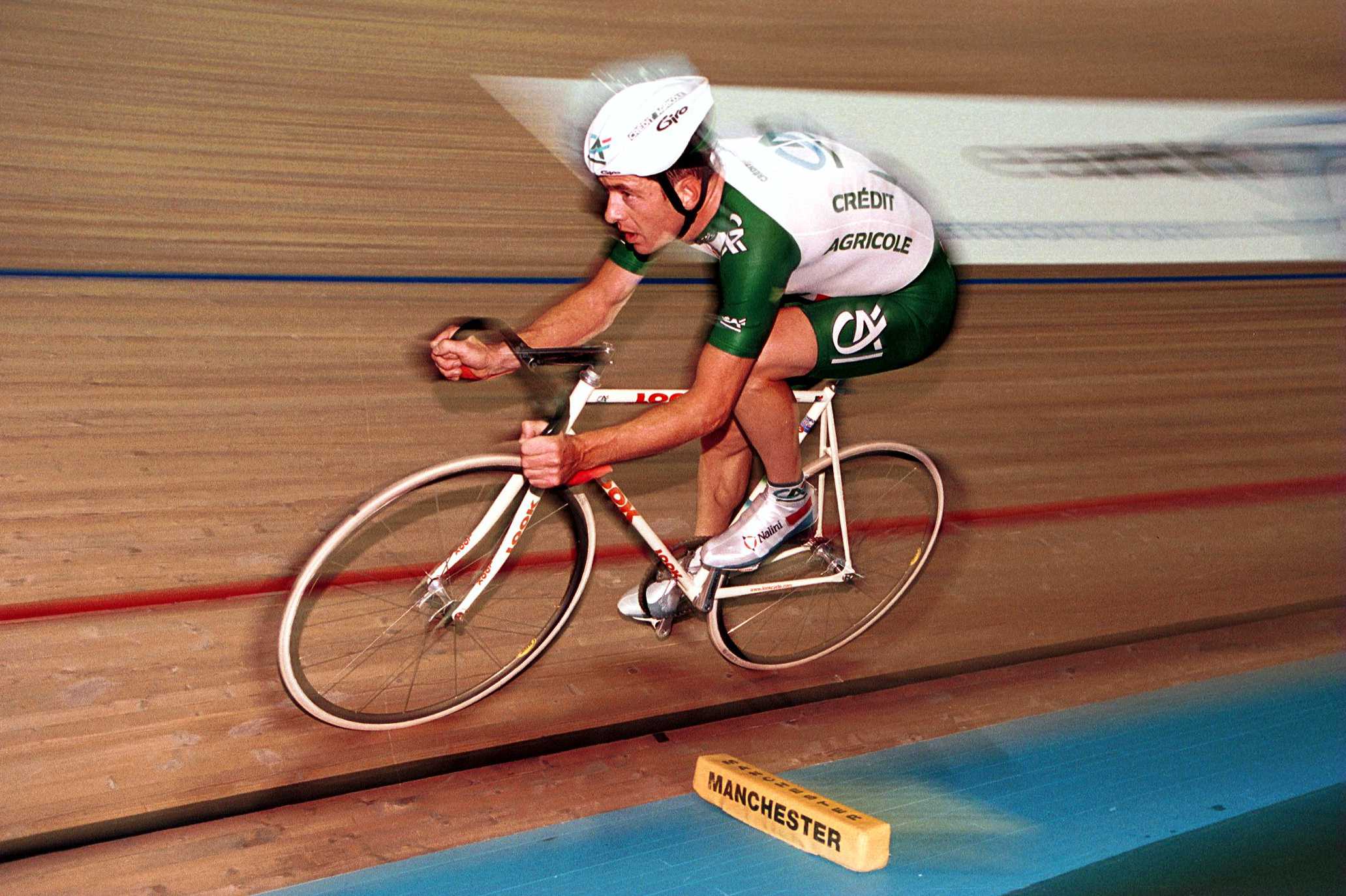

The new Hour record standard became known as the Athletes Hour, and had the effect of reducing it to a backwater event. In one of the final rides of his career, Chris Boardman set a new mark in Manchester in October 2000. But the appeal of what now looked like a nostalgia event had been greatly diminished.

When the Athletes Hour was finally scrapped in 2014 it had the effect of rejuvenating the record, instigating a flood of attempts. Since then there have been 35 attempts on the record, with the women's mark having been raised by nearly five kilometres to 50.267km (Vittoria Bussi) and the most recent men's holder, Filippo Ganna, having finally beaten Chris Boardman's 1996 superman record with a mammoth 56.792km.

2. First man home

As well as being a bit of a spectacle, the team time trial event can have some fairly major consequences for a stage race GC, with the team leader only being as good as the three or four behind them who must also cross the line before the clock stops.

Last year's Paris-Nice aimed to mess with this age-old formula by stopping the clock on the first rider over the line in its stage three team test. This left the team leader with the decision of if and when to romp away from his comrades, having first made the most of the advantage to be gained from riding in a team.

In the event, it was hardly revolutionary and most teams rode largely together until the final kilometre. Jonas Vingegaard finished within the bosom of his team, although fans were treated to the sight of Tadej Pogačar sprinting alone through the final bends, so it wasn't all in vain.

3. Raising the UCI weight limit

In an age when building a safe and viable race bike that undercuts the 6.8kg weight limit is straightforward if you've got a bit of money to spend, the idea of raising the limit seems incongruous. But when Ineos Grenadiers engineering guru Dan Bigham speaks, it's generally wise to listen.

Asked by Peak Torque YouTube channel which UCI rule he would change, new European double pursuit champ Bigham said, "I would increase the minimum weight limit to eight kilos. In fact maybe slightly more.

"At the moment there's this stupid push to be at the weight limit, and I understand why from a 'racing up a hill really fast' perspective," he explained. "However, you don't really get the best of engineering, the best of performance… because of the limit. No one wants to run cameras, or onboard sensors… or figure out another optimal because they don't have the weight to play with."

Increasing the limit, he argued, would give riders and teams more freedom to run any number of sensors, and designers the opportunity to create "more funky, weird designs that we can't even think about now because all we can think about is keeping the frame at 800 grams or whatever.

"Within cycling, that is the way we need to go," he said.

It could work. You might wish you spent less on that super-light bike though.

4. Limited hydration

While some recent rule suggestions might raise an eyebrow, few of them can hold a candle to the bonkers rules set out by Tour de France founder Henri Desgrange. Unfettered by the weight of history and tradition – and of course by the fact that it was his own race – Desgrange treated the Tour like a blank canvas, daubing clumsy rules all over it, all seemingly designed to make life harder for the riders.

One of the harshest was surely the stipulation that riders could only take on four bidons during the course of a stage. Riders could set off with two and be handed up two more. This was a rule that endured until the 1960s, in an era when stages were often far longer than anything the Tour de France sees today – the 1950 Tour, for example, featured three stages of more than 300km.

At the time, conventional wisdom dictated that drinking too much inhibited performance. It didn't stop riders getting thirsty though. No wonder they resorted to bar raids and filling up from village fountains.

5. A whole-Tour de France team time trial?

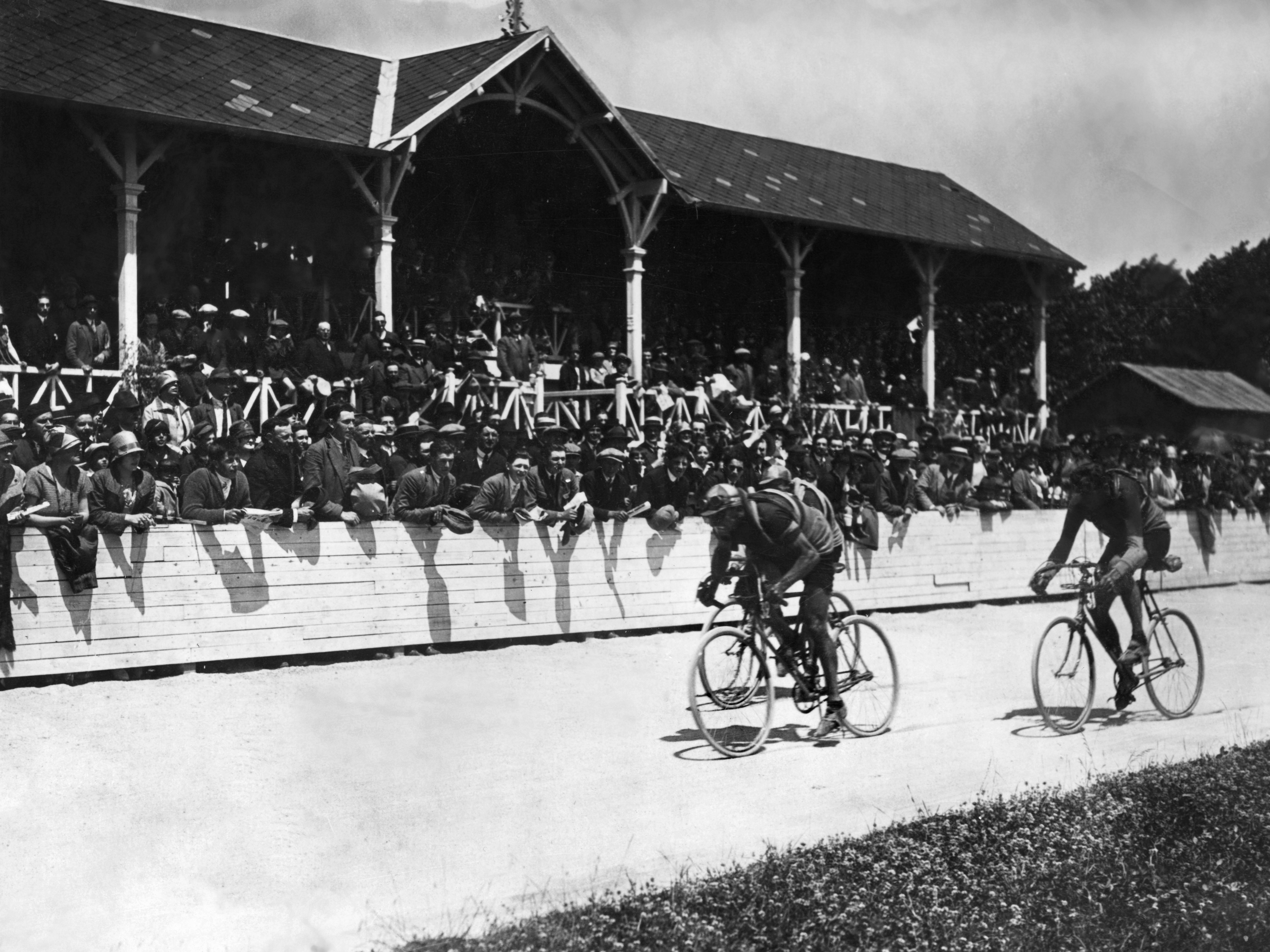

Almost. In the late 1920s, bristling at what he saw was slacking in the bunch, Desgrange ran off most flat stages as team time trials. This had the effect of forcing the riders to go all-out from start to finish for fear of falling down the GC. It also meant no hiding in the wheels, for anyone.

It was a strategy that didn't last long. It bored the public and made the Tour even less of the individual mano-a-mano that Desgrange craved. The idea was all but abandoned in 1929 to the great relief, you imagine, of all involved.

After cutting his teeth on local and national newspapers, James began at Cycling Weekly as a sub-editor in 2000 when the current office was literally all fields.

Eventually becoming chief sub-editor, in 2016 he switched to the job of full-time writer, and covers news, racing and features.

He has worked at a variety of races, from the Classics to the Giro d'Italia – and this year will be his seventh Tour de France.

A lifelong cyclist and cycling fan, James's racing days (and most of his fitness) are now behind him. But he still rides regularly, both on the road and on the gravelly stuff.