Iconic Places: Sestriere

The Tour will cross the 2,033-metre high climb of Sestriere en route to Pinerolo. We covered this historic climb in the June 2009 edition of Cycle Sport.

Words by Chris Sidwells

Wednesday July 20, 2011. Originally appeared in June 2009

“Lots of passion, stubbornness, capability for suffering and willpower. That is how I won on Sestriere.” Claudio Chiappucci.

The scenery is straight from a chocolate box. Classic pine-studded Alpine meadows create a feeling of space while still being surrounded by dazzling white peaks. It’s a tranquil haven under a piercing blue sky with air that could bring back the dead. This is Sestriere.

Sestriere sits next door to the Col de Montgenèvre. Today they lie on either side of the French-Italian border, but years ago the Montgenèvre was the Passo di Montginevro and was part of Italy. Sestriere, too, is so close to France that that it gets confused with its French name, Sestrières. And, unusually, both climbs have featured in both Tour de France and Giro d'Italia.

Sestriere is the ski resort at the top of the Colle Sestriere, which is the name of the climb. It’s not a long one, nor particularly hard, but iconic because of its strategic location and because of the men who made it so. The climb provided the canvas for an exhibition of cycling as art by the master, Fausto Coppi, who won over the climbs into Pinerolo in the 1949 Giro.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

As well as that win, Coppi won when the Tour de France first visited Sestriere in 1952, two days after the first ever summit finish at L’Alpe d’Huez. Claudio Chiappucci had an amazing day in the 1992 Tour de France to win in Sestriere. Miguel Indurain won a Giro stage on Sestriere and saved a Tour de France there. Lance Armstrong surprisingly won his first Tour mountain stage in Sestriere in 1999.

Roman route

Sestriere lies in the Valle del Chisone, which used to be the most important Alpine route from Italy into France. That changed in 1980 when the Fréjus Tunnel opened.

The Sestriere route was forged by the Roman military leader Pompey in 77BC. The Romans marked their roads with equidistant stones, and Sestriere comes from the Latin, Petra Sextreria meaning the sixth stone. In this case the sixth stone on the route from Turin.

Pompey picked his Alpine crossing because it was a direct, relatively low way into southern France, and from there across to Spain, but that fact also made it attractive to Rome’s aggressors. This is the way Hannibal took when he crossed the Alps.

Italian and Spanish cyclists have followed the adventures of Pompey and Hannibal over the Colle Sestriere. The first time a bike race crested the climb was on May 23, 1911, during the third running of the Giro. The organisers were keen to include a 2,000-metre climb, to match the Tour de France, which had made its first true excursion into the mountains the previous year when it tackled two stages in the Pyrenees.

The Giro stage ran from Mondovi to Turin. Not too far as the crow flies, but the riders were sent on a loop up the Vale del Chisone, over the Colle Sestriere and back down the Valle di Susa, a route totalling 302 kilometres. Lucien Petit-Breton, a Frenchman who grew up in Argentina, led over the climb and won the stage in a sprint from co-escapees Carlo Galetti and Ezio Corlaiti to become the first foreign stage winner in the race.

The Fiat connection

Petit-Breton was a foreigner, but even in the partisan days just before the First World War he still very popular in Turin, because was riding a Fiat bike. Fiat and Turin are inextricably linked; the name FIAT is an acronym for Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino. The automobile and financial giant was founded in Turin, the capital of the Piemont region, in 1899 by a group of investors including Giovanni Agnelli.

Sestriere is also in Piemont, and when he was a regional senator, Agnelli pushed through the development to turn Sestriere into the ski resort it is today. It has been a frequent host to ski world cup events and was the site for Alpine skiing in the 2006 winter Olympics.

The Colle Sestriere next appeared in the Giro in 1914, when torrential rain, freezing cold and low cloud produced a stage full of confusion. Conditions were so bad that no record exists of who went over Sestriere first. All we know is that Angelo Gremo was 14 minutes clear of the next rider when he arrived at the finish in Cuneo, and that he took 17 hours to complete the 424 kilometre marathon stage from Milan.

Three-way split

There are three ascents of the Colle Sestriere, two from the west and one from the east. The Giro has used all three, but the Tour has only climbed from the west. One western ascent starts at the foot of the Montgenèvre descent, which is the way Coppi went on his Giro and Tour triumphs. And the other starts in Oulx, over in the Susa valley, which is the way Claudio Chiappucci climbed for his 1992 Tour de France stage win.

The Oulx and Montgenèvre ascent meet in Cesana-Torinese, which is the start of the serious climbing. The climb begins with two wide hairpin bends, and the second and third kilometres are the two hardest. For some that fact makes Sestriere a tougher climb than its gradient and length suggests.

Vittorio Adorni, who won the 1965 Giro, explains. “When a climb is steep straight after a descent it is always a gift for a climber. Riders like me, who were more all-rounders, need to settle into a climb, but when the steepest bit comes first that is very difficult to do. We climbed Sestriere in 1964 and I was in a break coming off the Montgenèvre with Jacques Anquetil, Gianni Motta and Franco Bitossi, but I lost contact on the first slopes of Sestriere. By the time I got back, Bitossi had attacked and gone off to win the stage.”

Mountain circle

At the third kilometre the road levels slightly as it crosses under a ski lift. Big curves give way to wiggles after another short pitch of eight per cent. The road slowly begins to straighten as the first views of the mountains that surround Sestriere appear.

The most prominent peaks are the two that stand either side of the pass, the Monte Fraiteve and Monte Sises. A look behind at this point reveals the ridge of mountains that form the French-Italian border. Some of them are well over 3,000 metres high and they add to the majesty of Sestriere, expanding into a spectacular horizon.

The road steepens again at Champlas du Col as another set of wide hairpins help reduce the gradient to a manageable seven per cent. Nine hundred people live in Sestriere, but there are 6,000 hotel beds and another 2,000 apartment rooms. One look down the Valle del Chisone from the top is all that’s needed to see why this place is so popular.

Up here on a beautiful day it’s impossible to imagine the terrible weather that forced the organisers to shorten the 1996 Sestriere stage. The stage would have been one of the most difficult in the last two decades, running from Val d’Isere over the giant Col d’Iseran and then the Col du Galibier via the harder north side before finishing at Sestriere. But the morning of the stage saw snow and gale force winds over the high passes, and the riders covered most of the stage in their team cars, until it was decided that they would race from Le Monétier les Bains, on the descent of the Lautaret, below the Galibier. The race would cover 46 kilometres, over the Col de Montgenèvre, and then up to Sestriere.

Bjarne Riis, tanked up on EPO, won the stage, and took the yellow jersey which he would defend to the end of the race. Although the stage was short, it was run off at such a fast pace – 39kph, mostly uphill - that 57 riders would have been eliminated if the organisers hadn’t waived the time limit rule.

But it is Claudio Chiappucci's stage win here in 1992 that is the mountain's most famous recent appearance in the Tour. The Italian attacked at the start of the stage, and held off the entire peloton for 200 kilometres before winning solo.

Five top men of Sestriere

Fausto Coppi

The ‘Campionissimo’ is the number one rider at Sestriere because he led over the climb in the Giro, and he won the first Tour de France stage that finished there. Both days were a demonstration of total cycling superiority that only Eddy Merckx has been able to equal. On the Cuneo-Pinerolo stage in the 1949 Giro. Coppi went clear with 192 kilometres to go to sail over four mountain passes and win by 11 minutes. He won the Giro d’Italia and later the same year he won the Tour de France, the first man to complete the double.

Coppi did it again in 1952, winning the first Tour de France stage to Sestriere, the day after going into the history books as the first winner on Alpe d‘Huez. The late forties and early fifties were the height of Coppi’s career, and he was credited with restoring Italy’s self respect after the Second World War.

Claudio Chiappucci

Coppi’s exploits were the soundtrack of Chiappucci’s childhood. His father, a frustrated racer, was a huge Coppi fan. He had been a prisoner of war with Coppi, sometimes giving the great man his own food to keep his strength up. Chiappucci picked the St Gervais to Sestrieres stage of the 1992 Tour as the one where he would achieve his biggest exploit. “I prepared for it, focussed on it. The stage ended in Italy, and I never did race tactically. If I had, Miguel Indurain would have still beaten me anyway,” he says now.

At least this way Chiappucci was spectacular. He was already wearing the polka-dot jersey when he attacked on the Col de Saises, and in the next five hours he tied up the mountains competition. He led over the Cormet de Roselend, then on the 2,770 metres Col d’Iseran he dropped his last companion, Richard Virenque. Chiappucci kept the pressure on over Mont Cenis and won in Sestriere.

Behind him it was carnage, with everyone apart from Miguel Indurain slowly losing their chance of winning the 1992 Tour. The best of the rest on the day were Franco Vona, Indurain, Gianni Bugno and Andy Hampsten. Indurain took over the yellow jersey with everybody apart from Chiappucci effectively eliminated.

Miguel Indurain

As well as closing down Chiappucci on Sestriere in the 1992 Tour, Miguel Indurain sealed his 1993 Giro d’Italia victory on the climb, from the east side. The stage was tailor made for Indurain - a 55-kilometre time trial beginning in Pinerelo and ending in Sestriere. After 17 kilometres of flat road the riders faced the ascent of Sestriere; 38 kilometres of gradually steepening uphill that gained 1,425 metres at an average gradient of just under four per cent. Indurain steamrollered the course, using the flat part to shock and awe his rivals, then not showing a chink of weakness on the uphill. He beat Piotr Ugrumov by 45 seconds, with Moreno Argentin a distant third, over two minutes behind.

Franco Bitossi

Bitossi’s nickname was “Crazy Heart”, thanks to the tachycardia-like condition which caused his heart to zoom up to 220 beats per minute, then return to normal. A strong climber and sprinter, he didn’t quite live up to his abilities. Today he thinks some of that could have been due to nerves. For example, he could never bring on his heart problem during a medical test. “It only happened in races, and when it came I had to stop by the road to let it pass,” he said recently.

At the beginning of his career Bitossi was a climber. He won the Giro King of the Mountains classification three times in a row, beginning in 1964 when he took the celebrated Cuneo to Pinerolo stage. It was one of Bitossi’s great days, and he chose Sestriere to drop a break containing Vittorio Adorni, Gianni Motta and the eventual Giro winner that year, Jacques Anquetil.

Giuseppe Saronni

The Lampre team manager was one of the best racers of his generation. By 1982 he had already won the Giro once, and had begun building his total of 24 stage wins in the race, but he was also busy fighting out a rivalry with Francesco Moser. The 1982 Giro had a Cuneo to Pinerolo stage. It was the ’Taponne’ as the Tifosi call the biggest, most dramatic stage of each Giro. With two climbs to go, the Montgenèvre and Sestriere, race leader Bernard Hinault was isolated in the lead group, while second overall, Sweden’s Tommy Prim, had two team mates.

But for some reason Prim would not attack. The group took the Montgenèvre sedately, then Saronni, who was sixth overall, attacked on Sestriere. But he only wanted to get rid of Moser, and didn’t press home the advantage. Hinault followed, so did Prim, and Saronni made short work of the sprint to win in Pinerolo. Saronni is a native of Piemont, so the win meant a lot, almost as much as leap-frogging his nemesis Moser in the general classification.

Pro's eye view

Eleventh place finisher in the 2005 Giro Wim Van Huffel recalls his Sestriere experiences

Tell us about the Sestriere stage

We climbed to Sestriere twice that day, both times from the east, which is a long climb but not too steep. The key climb that day though was the Colle della Finestre. That is an epic climb.

What is the Sestriere climb like?

It’s not too hard. Or it wasn’t the first time we climbed it, but the second time was tough. The Finestre had been a real struggle and the descent was very technical, very hard on the nerves. A nervous descent can leave you with dead legs for a climb We didn’t have too much of Sestriere left to climb, but all of the front riders were done in by then.

Did you ride hard on the Finestre?

Yes, it was my first Giro and I wanted to improve my overall position, and the riders around me on the classification were falling behind. I moved up that day.

Do you think that helped Savoldelli?

Yes, but it helped me more.

Is there a secret to a climb like Sestriere?

Yes, but it’s the same as any other climb, you must respect it. The east side is very, very long and even though it isn’t steep, nearly 40 kilometres of climbing is still a big strain. If you ride there you must remember to vary your position. If you go all that way in the saddle you can tire the muscles of your back. Even though it isn’t steep, you need to get out of the saddle from time to time to ease you back and let your arms and shoulders help your legs a bit.

You talked about descending affecting your legs for the next climb. Is there anything you can do on a descent to help your legs?

You must eat. Riders get to the top and forget about eating, but sometimes the fight of going up keeps you from realising how hungry you are. Try to keep warm with a rain top maybe, and don’t keep your legs still in the free-wheel for long periods.

Cycle Sport's Tour village: All our Tour coverage, comment, analysis and banter.

Follow us on Twitter: www.twitter.com/cyclesportmag

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.

-

'This is the marriage venue, no?': how one rider ran the whole gamut of hallucinations in a single race

'This is the marriage venue, no?': how one rider ran the whole gamut of hallucinations in a single raceKabir Rachure's first RAAM was a crazy experience in more ways than one, he tells Cycling Weekly's Going Long podcast

By James Shrubsall

-

Full Tour of Britain Women route announced, taking place from North Yorkshire to Glasgow

Full Tour of Britain Women route announced, taking place from North Yorkshire to GlasgowBritish Cycling's Women's WorldTour four-stage race will take place in northern England and Scotland

By Tom Thewlis

-

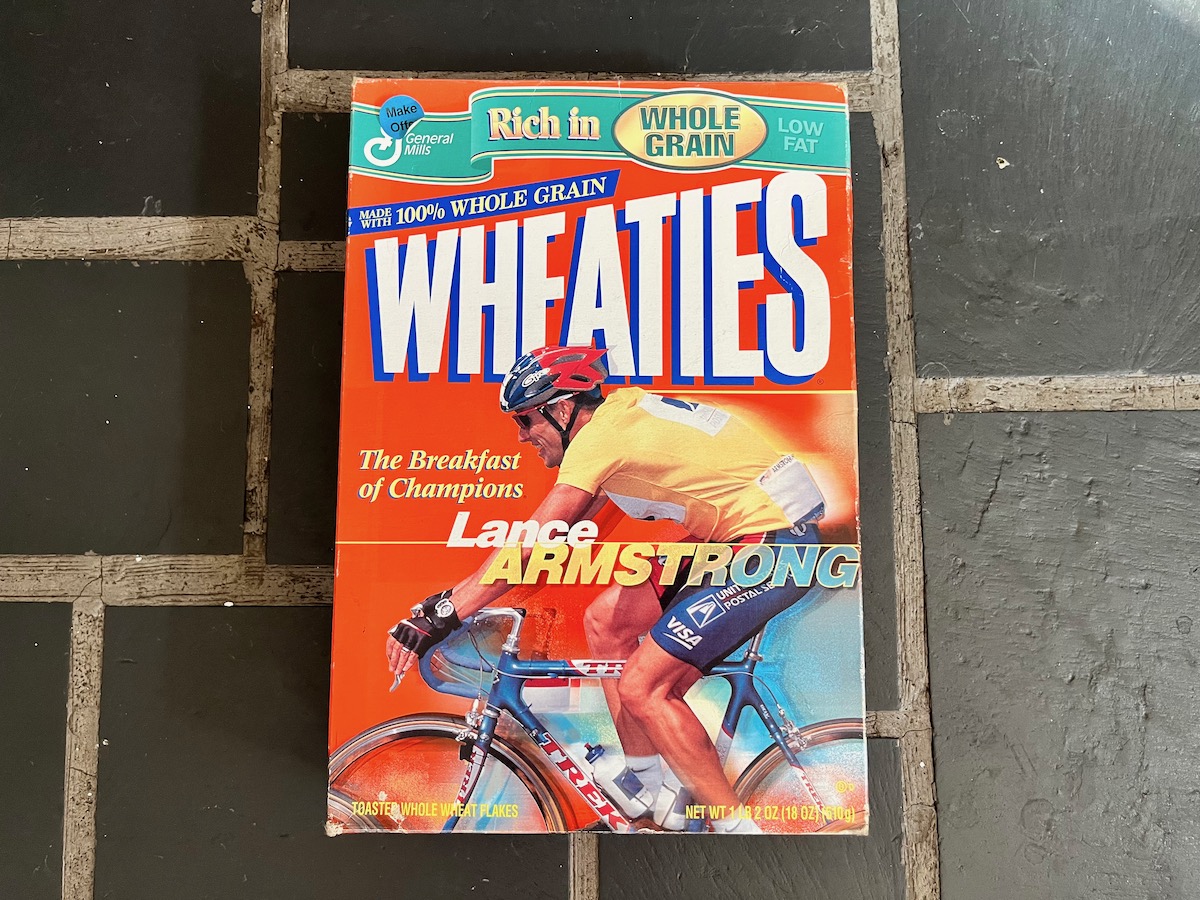

Will another cyclist ever follow Lance Armstrong onto a Wheaties box?

Will another cyclist ever follow Lance Armstrong onto a Wheaties box?USA Cycling is optimistic about the ‘strongest US men’s presence in Europe’ in nearly two decades with contenders for future Tour de France race.

By Anne-Marije Rook

-

Former French Anti-Doping boss accuses Lance Armstrong of motor doping

Former French Anti-Doping boss accuses Lance Armstrong of motor dopingVerdy says he doesn't think Armstrong's performances were possible on just EPO alone

By Jonny Long

-

Lance Armstrong tips Mathieu van der Poel to win Tour of Flanders

Lance Armstrong tips Mathieu van der Poel to win Tour of FlandersLance Armstrong has tipped Mathieu van der Poel to win the Tour of Flanders this weekend.

By Alex Ballinger

-

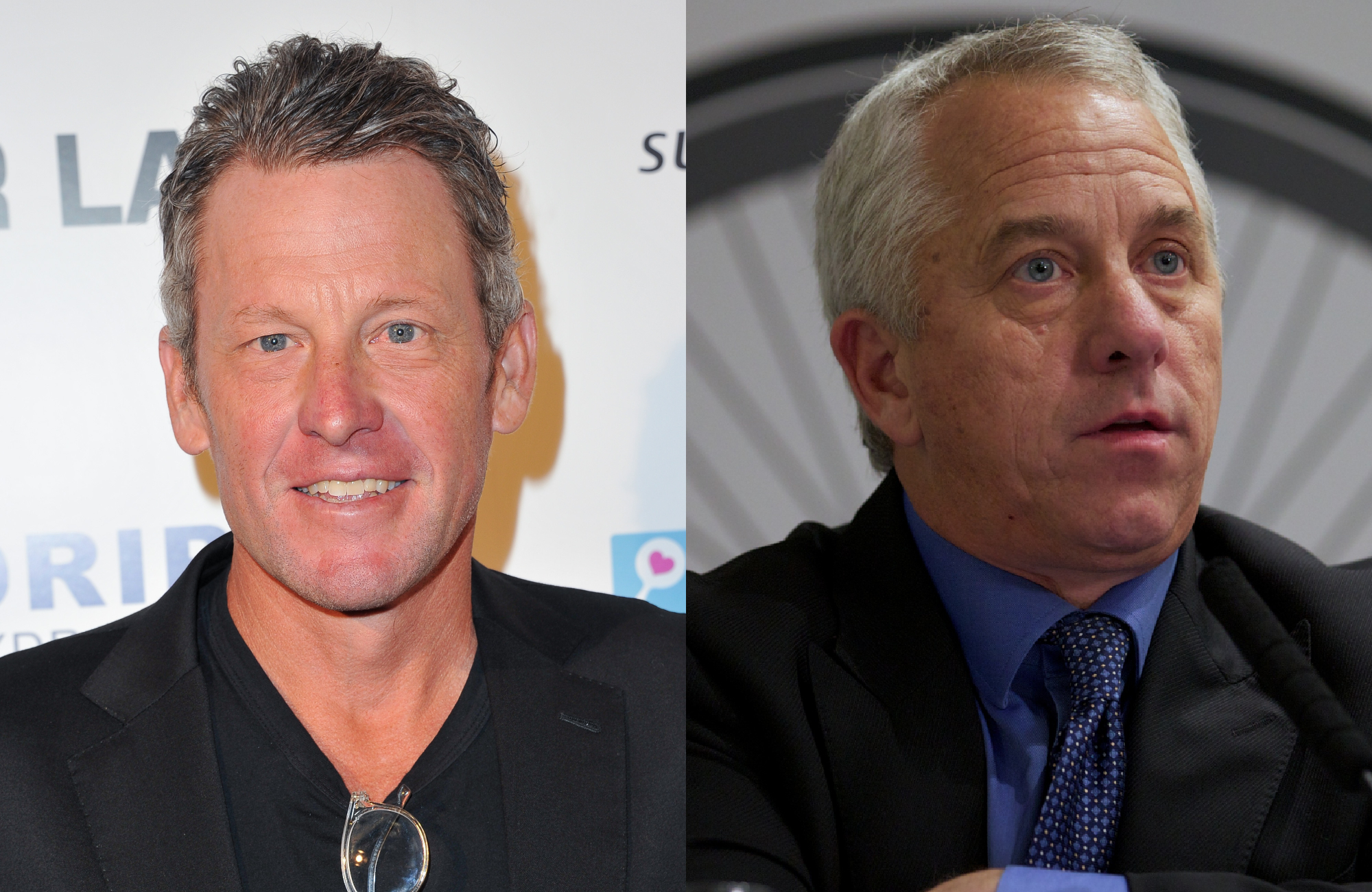

Lance Armstrong could have won without the drugs, says Phil Liggett

Lance Armstrong could have won without the drugs, says Phil LiggettLance Armstrong would have won the Tour de France with doping, according to legendary cycling commentator Phil Liggett.

By Alex Ballinger

-

Lance Armstrong would have been the best of his generation even without doping, claims Johan Bruyneel

Lance Armstrong would have been the best of his generation even without doping, claims Johan BruyneelLance Armstrong would have been the strongest rider of his generation even without doping, Johan Brunyeel has claimed.

By Alex Ballinger

-

Johan Bruyneel says he won't watch the Lance Armstrong documentary as he 'already knows what happened'

Johan Bruyneel says he won't watch the Lance Armstrong documentary as he 'already knows what happened'The former US Postal Service boss is currently serving a lifetime ban from cycling

By Jonny Long

-

Lance Armstrong says he didn't like the Greg LeMond part of the ESPN documentary

Lance Armstrong says he didn't like the Greg LeMond part of the ESPN documentary'There are still very specific things that I think still upset him,' said the film's director

By Jonny Long

-

Tyler Hamilton suggests Lance Armstrong still hasn’t told the whole truth in new documentary

Tyler Hamilton suggests Lance Armstrong still hasn’t told the whole truth in new documentaryTyler Hamilton has suggested Lance Armstrong still hasn’t told the whole truth in a revealing new documentary.

By Alex Ballinger