Barry Hoban: A British cycling great

Barry Hoban’s tally of Tour de France stage wins beats every British rider bar Mark Cavendish. There’s much more to Hoban than his palmarès, though, as Chris Sidwells found out when he visited him at home in Wales

Barry Hoban sometimes gets overlooked. That’s not just my opinion, it’s the opinion of people like Graham Jones, who followed Hoban into the pro peloton.

The media were all over Brian Robinson in the run-up to the Yorkshire Grand Départ, whereas not much was seen of, or heard from, fellow Yorkshireman Hoban. OK, Robinson lives in Yorkshire and Hoban lives in Wales now, but that doesn’t fully explain the discrepancy.

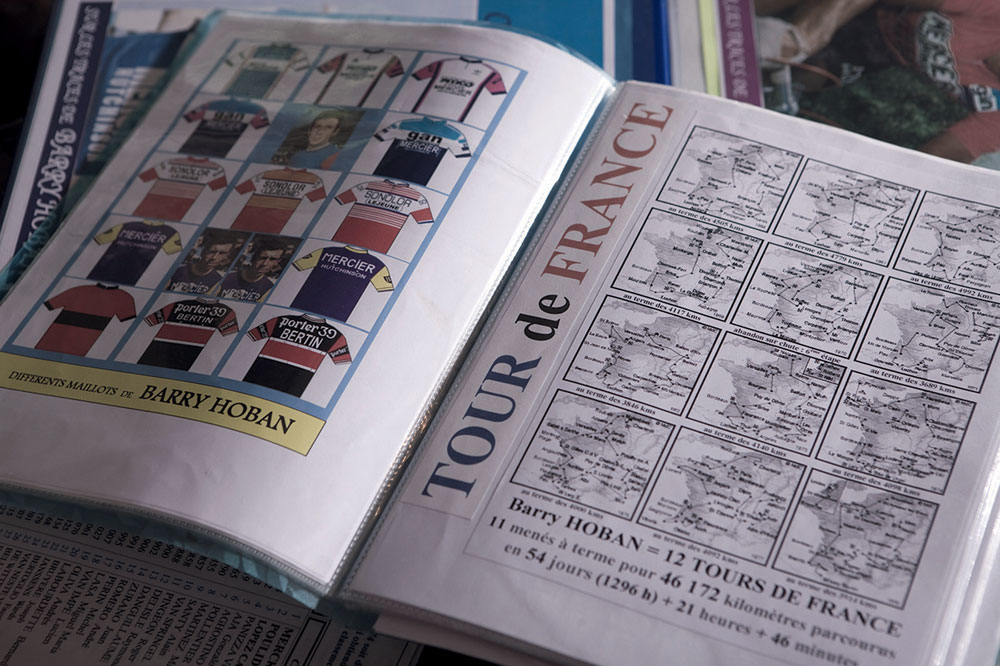

Look at Hoban’s record; it’s broader, deeper and covered a longer timeframe than Robinson’s, both in the Tour de France and in other races. Hoban was a pro from 1964 until 1980, 16 years in which he also set the British Tour de France participation record with 11 finishes from 12 starts. He won races throughout, from 1964 until 1980.

Only Mark Cavendish is ahead of Hoban in the British Tour stage-win rankings, and Hoban’s eight wins are still way ahead of the rest. He is second in the rankings of British riders in number of podium places in Monuments, too, with three podium finishes, in which regard only Tom Simpson is ahead of him.

Hoban was the first British winner of a Tour de France mountain stage, the first British rider to win two Tour stages in a row, the first to win a stage in the Vuelta a España. He’s also the only Brit to have won the Classic Ghent-Wevelgem, in 1974.

Barry Hoban

Then there’s Hoban the man. Aged 74, he’s larger than life with a total racing recall, he’s a great storyteller, an interviewer’s dream. Currently I’m helping him write his autobiography, the one he says he wanted to write just after he stopped racing, and it’s going to be a humdinger.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

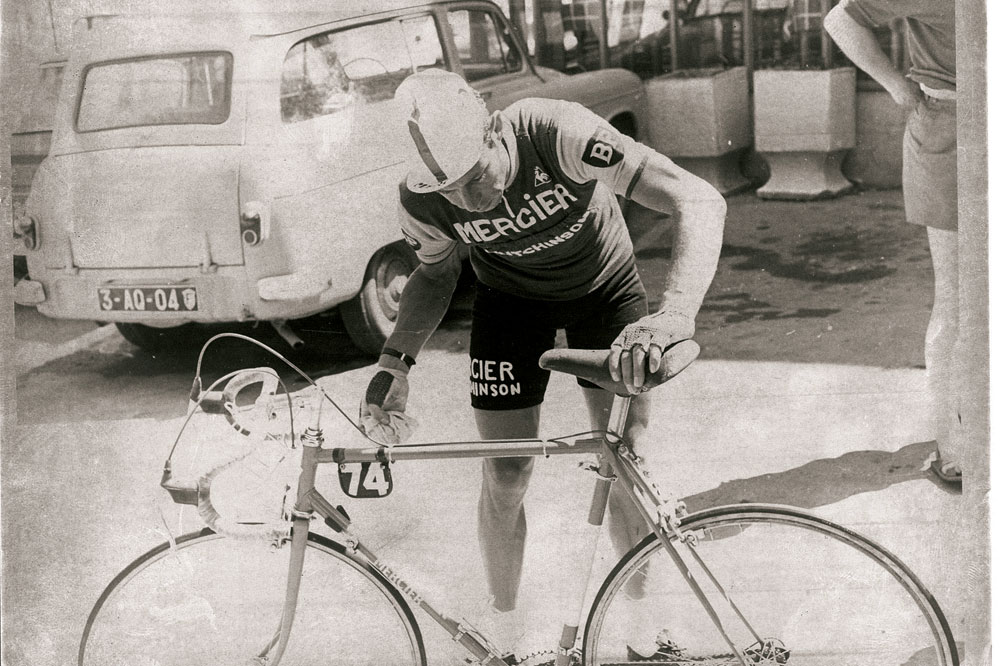

But Hoban doesn’t always get the credit he deserves. His first team manager, Antonin Magne, didn’t understand him, and told him that he lacked something. Hoban felt like an outsider in Magne’s Mercier BP team, which he signed for when he turned professional.

“Hoban is maybe too straight-talking for the cycling mainstream”

Similarly, he’s always felt a bit outside of British cycling. He was the logical choice for national coach when he stopped racing, but he wasn’t offered the job, and his ability to analyse races and predict moves has never been put to good use. Instead, he made his post-racing career in the cycle industry, running a bike factory in Wales, from which he’s just retired at 74.

The truth is Hoban lacks nothing in terms of cycling expertise; maybe he’s just too straight-talking. He calls it as he sees it, as he always has, and not everybody can handle that. Hoban was a hard racer, a fierce competitor and no believer in false modesty. But he could ruffle feathers, especially on home turf.

Contrast to Robinson, who is equally tough, but it’s a toughness that is deep and, with the passing of years, well hidden. With Hoban, the hardness of attitude remains unconcealed.

British pioneer

Hoban was the third British pioneer to make his mark on the Tour de France and the wider pro peloton. Robinson was first, then came Tom Simpson, then Hoban, who turned pro in 1964 when Simpson was already one of what Hoban calls: “The top table, les Gros Bras”; Robinson had retired.

Simpson won the Tour of Flanders in 1961, wore the yellow jersey at the Tour in 1962 and finished number two in the world rankings in 1963 and 1964. While Hoban was finding his feet as a new pro, Simpson won Milan-San Remo. Their career trajectories were very different.

When Simpson had turned pro, he joined Brian Robinson in the St Raphaël team, and as such he got a lot of guidance from Robinson, something Hoban never got. Yet Simpson saw Hoban as a rival.

Hoban was a good track racer as an amateur, just like Simpson, whose natural speed suited European-style racing. Seeing his success, Hoban thought: “If Tom can do it, then so can I.” And so Hoban moved to northern France in 1962 to race as an independent, just like Simpson had done when he moved to Brittany in 1959. And it wasn’t long before Simpson heard how good Hoban was.

The pair rubbed along OK and there was certainly no animosity. Hoban accepted Simpson’s class and admired the way he raced. “Tom won lots of races because he attacked a lot,” Hoban said. “In a break, he could look after himself. Tom had a good head, and he could sprint.”

At the 1965 World Road Race Championships, Hoban was unstinting with his effort to help Simpson win the rainbow jersey, driving the front group and setting up Simpson to make the victory move.

But there was one occasion, early in Hoban’s Continental career, when the rivalry surfaced. It was 1963 and Hoban was still an independent rider, a classification that was a halfway house between amateur and professional.

He was allowed to ride certain pro races, and in one of them, the Paris-Luxembourg, he had been dropped from the breakaway group. Simpson had his Peugeot team chasing behind, but only until Hoban was caught, then they stopped. Hoban’s directeur sportif asked Simpson why he had chased like that, and Simpson said: “Because I’m the number one British rider on the Continent, not Barry.”

British number one

Simpson died in the 1967 Tour de France. Meanwhile, Alan Ramsbottom, another British pro racing in Europe at the time, had become disillusioned and returned home.

Vin Denson, another Brit who was a domestique for the two Sixties greats — Rik Van Looy and Jacques Anquetil — and a team-mate of Simpson’s in the Tour when he died, should have joined Simpson in an Italian team for 1968, but he lost his desire and returned home, too.

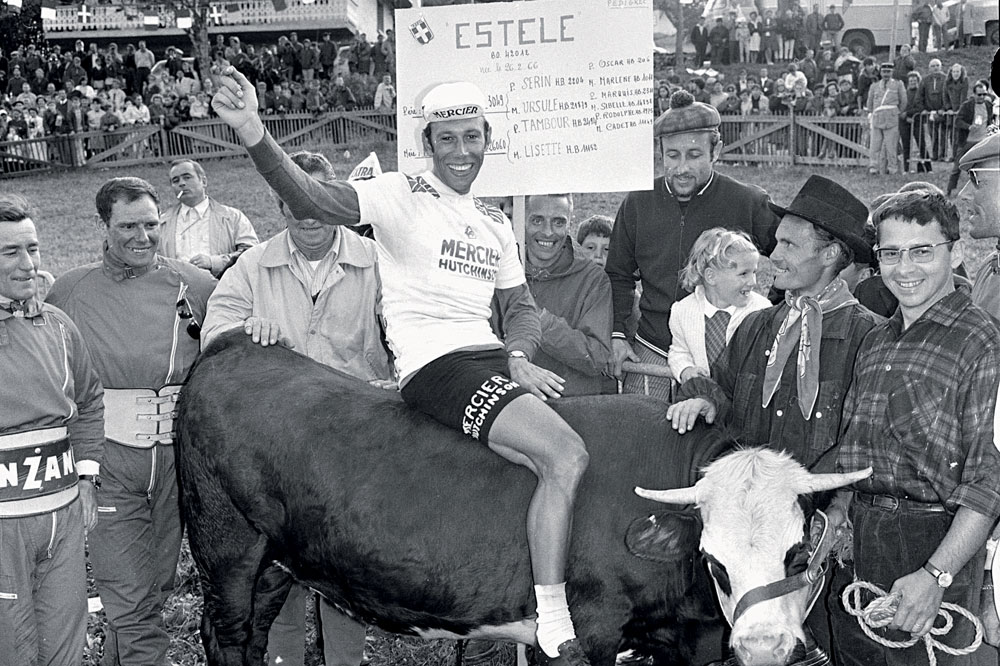

Hoban, as a British rider, was alone. And that’s when he started to come good. He had already won two stages in the 1964 Vuelta, he won the 1966 Henninger Turm race, a semi-Classic in Germany, and at the Tour de France in 1967, he was given the stage on the day following Simpson’s death.

“Once ready, I’d look at myself and say, ‘OK Bazza, it’s down to you"

And with Britain’s main man gone, Hoban stepped up to lead the 1968 Tour de France team. He won a stage alone in the mountains at Sallanches, finished 33rd overall, seventh in the points classification and sixth in the King of the Mountains. At which point he was the number-one Brit in Europe, and it would stay that way for many years to come.

Hoban had a gruelling first year in cycling. “No one could have done more races than I did. I did Paris-Nice, Milan-San Remo, the cobbled Classics, then the Tour of Spain, which started in April back then. After that, for my first Grand Tour, Monsieur Magne thought I might need a little leg-stretcher so he put me in Bordeaux-Paris.

“Then, so I didn’t get bored before the Tour de France, he had me do the Midi Libre stage race. I rode the Tour, and after that I had a month of post-Tour criteriums. Then there were the end-of-season stages races, then a load of semi-Classics like the GP Fourmies, then Paris-Tours and finally the Tour of Lombardy.”

Not even the most seasoned pro rider today has a programme as full as Hoban’s was. For example, aged 24, he rode Bordeaux-Paris — a one-day race that was 560km long, just after he finished his first Grand Tour.

Hoban wasn’t only riding for himself in those races either. His two stage victories in the 1964 Vuelta came while he was working for team-mate Raymond Poulidor’s overall victory. Poulidor came close to winning the 1964 Tour as well, too, but Jacques Anquetil just edged him; Hoban was in the thick of the action.

Mr Meticulous

It took Hoban most of the next year to recover, and later he still had problems, like an abscess that required surgery just before the 1967 Tour. But when his form returned, he was good — like when he rode in a race-long break to finish fifth in the 1967 Tour of Flanders, and took second in Paris-Tours the same year.

Listening to Hoban talk about his racing, you realise that Team Sky’s focus on ‘marginal gains’ is nothing new; riders like Hoban were paying attention to small details years ago. “I had this thing about going into meticulous detail,” Hoban said.

“I didn’t want to be let down by anything I could foresee and prevent. So before every race I did an inventory: new shoelaces, clean shiny shoes, new handlebar tape, my bike working perfectly with correct gear ratios etc.

“When I was ready, I’d look at myself and say, ‘Yes, the shoes are perfect, ankle socks spot-on, the legs are nicely shaved, nicely tanned, nicely oiled, everything is perfect. The bike is in immaculate condition.’ Then I’d say, ‘OK Bazza, the only thing that’s going to let you down is you, everything else is perfect.’”

That attitude is just like a one-man Team Sky approach. Control the controllables and then work on your mind, establishing with confidence that everything that could be done has been done.

Another skill Hoban had as a pro — and still has today — is a total recall of a race, just like Mark Cavendish, who is able to remember every detail of a race route. Hoban described the sprint finale of the 1967 Paris-Tours, where he finished second to Rik Van Looy, almost 50 years after he raced in it.

“We’re coming in toward the finish, coming along the side of the River Loire,” he said. “You go down to one of the bridges, turn over the bridge, then go up the other side of the river to the finish. I knew the guy to beat was Rik Van Looy.

Van Looy was the greatest Classics rider ever, the only one to have won every single Classic. Eddy Merckx was great, super-Merckx, the Supremo, the best ever, but he never won Paris-Tours.

“Anyhow, we’re coming along with five or six kilometres to go and I was right on Van Looy’s back wheel. But then he looked behind, saw me and freewheeled. I thought, ‘What’s he doing?’ And he’s still not pedalling, and suddenly there’s a 10-metre gap… then a 20-metre gap…. then a 50-metre gap.

We’re losing. The race is going up the road and he’s losing and doing nothing about it, but I’m losing too. I thought, ‘He must be a hell of a poker player.’ Then I chickened out.

“I accelerated, and as I did, bang, Van Looy latched on to my back wheel and stuck there. I went straight through to the front and into the sprint, with Van Looy still on my back wheel.

And then I waited. I waited for Rik Van Looy to jump. And that was fatal. He had thighs like my waist used to be and when he jumped, wow, he took three lengths out of me in an instant.

“I went after him, and there was [Walter] Godefroot there, there was José Samyn there, both good sprinters, but I flew past them. I came back at Van Looy all the way up the finishing straight; back, back, back. Then we flashed over the line and I was still half a wheel short. Fifteen metres more and I might have got him.

“So I was second, a good result, but I never sprinted that way again. I never let a sprinter jump in any subsequent Tour de France or Classic finish. I always went first, then they had to get round me, if they could.”

Barry Hoban: British Legends

Barry Hoban is one of Britain’s cycling greats. Now 70, he’s still just as passionate about the sport he loves

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast

-

Aero bikes with gravel wheels?: Six tech insights from Paris-Roubaix Femmes

Aero bikes with gravel wheels?: Six tech insights from Paris-Roubaix FemmesEverything we found out about tyre widths, self-inflating systems, and wheel choices from the cobbled Monument

By Tom Davidson Published

-

'This race is absolutely disgusting': Peloton reacts to another brutal Paris-Roubaix Femmes

'This race is absolutely disgusting': Peloton reacts to another brutal Paris-Roubaix FemmesNow in its fifth edition, Paris-Roubaix Femmes is still a tough race, even for the best bike riders in the world

By Adam Becket Published