Biodynamic food: Team Sky's new marginal gain (video)

We investigate whether specially cultivated, ethically produced food is really worth the extra cash

It’s all very well advocating clean sport, healthy training and fair competition, but what about the food you consume in the process? Has it been cleanly and ethically produced, or is it tainted by dubious chemicals and questionable farming practices?

In other words, are we risking double standards by obsessing about competitive pureness while ignoring the content of our plates? For an increasing number of pro cyclists, the answer is yes, as food standards become a new frontier for marginal gains.

Team Sky is as usual leading the way and taking this trend to its logical extreme. Planting and harvesting crops by the cycles of the moon? Embedding quartz into cow horns and planting them in the soil? These are some of the earthly practices underpinned by spiritual beliefs that constitute biodynamic agriculture — which, believe it or not, has been hailed Sky’s latest marginal gain.

>>> Sir Chris Hoy’s golden training rules

As the team’s new chef, James Forsyth aims to source the team’s food from biodynamic sources. Focusing on meat and animal protein in particular, Forsyth believes that biodynamic food production standards could improve the performance of the riders.

“In recognising the need switch to biodynamic or organic food, the team is all about marginal gains. Personally, I think it’s potentially a big gain,” he says.

Biodynamic food goes beyond the standards required of organic produce. Adhering to the controls and regulations set by Demeter International — the trademark organisation for biodynamic produce — food must be made without synthetic fertilisers or pesticides, and artificial additives are banned.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

>>> Ketones: Controversial new energy drink could be next big thing in cycling

What’s more, biodynamic farmers must stick to rigorous guidelines for protecting their soil, promoting the natural ecosystem, and farming in an ethical way. Setting aside the pseudoscience and dubious spiritual rationales, biodynamic is about getting as close to nature as possible.

“Biodynamic is basically where the mini ecosystem on which the animal would live is completely uncontaminated,” explains Forsyth, who worked in various top-end London restaurants before joining Sky.

“It means there are no chemicals within the meat, it’s 100 per cent natural,” he adds. “It [the animal] has just lived on grass its whole life; it’s had a stress-free life, and it has been killed in an ethical way. There is a big difference between that sort of meat and the type you would buy in a supermarket.”

Start your day like a pro

Where’s the science?

Crucially, though, will filling your plate with biodynamic food make you any faster? Thanks to its spiritual leanings, biodynamic agriculture suffers from a reputational problem: it’s regarded, with some justification, as unscientific, cultish, and frankly a bit delusional.

So before going any further, let’s clarify that most of the principles behind biodynamic food, in terms of its value to health, are unsupported by quality scientific evidence.

>>> How to carb load before an event or race

Celestial cycles enriching your food production, along with cow horns and the cosmos — it’s more religion than rationality. In most instances, the food, so far as conventional science is concerned, is no different from organic.

However, biodynamic farmers argue that getting bogged down in the mystical aspects misses the point entirely. Jody Scheckter is a former Formula 1 world champion who now runs an organic and biodynamic farm near Basingstoke.

Laverstoke Park Farm has even featured recently on the ITV reality show Sugar Free Farm where six famous faces attempted to cut out sugar from their diet. He argues that biodynamic is a comprehensive philosophy of food as much as it is about practical guidelines.

>>> Jens Voigt: Life lessons from 30+ years of riding

“Organic says you can’t do this and that, whereas biodynamic says you should do this and you should do that,” Scheckter tells Cycling Weekly.

“We follow nature very strictly, and we have two main things: slow-growing animals and plants are generally healthier and taste better, and biodiversity is a key to a healthy natural environment. That for me is the key to producing good food.”

Scheckter shuns processed food, with few exceptions. Having previously supplied Sky with fresh meat, he has also run his own abattoir, and still provides dried meat snacks such as jerky and biltong. His involvement with professional sport includes rugby clubs that were relying, he says, on poor diets with “nasty white bread”.

>>> Why stress can make you fat – and what to do about it

“Biodynamic food is what your grandmother would have called food,” adds Scheckter. “I think that sums it up.”

His outlook is shared by journalist and author Michael Pollan, an outspoken critic of the modern farming industry who contends that most of what modern Westerners eat is no longer the sort of stuff that previous generations would have recognised. Pollan’s philosophy is offered in one simple, boiled-down creed: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.”

Pure and simple

Besides the justifications on grounds of promoting a healthy and sustainable natural environment, cyclists might be drawn to the purity of biodynamic food.

There have been many cases of riders falling foul of food and supplements contaminated with banned substances, a risk for anyone adhering to the World Anti-doping Code.

There is a separate, though related, argument for reducing your use of supplements and focusing on getting the right nutrition purely through food.

Real food, as well as supplements, can be contaminated by chemicals. Whereas in biodynamic agriculture, animals are reared on grass, outdoors, with a focus on welfare from birth to slaughter, modern industrial farming has very different priorities — principally, profit.

>>> Should you hire a bike or take your own when you go abroad?

Food, in particular fruit and vegetables, can contain a range of artificial pesticides and fertilisers; while regulations limit the residues permissible on food to safe levels, campaign groups still point to the risks of low-level exposure and the ‘cocktail’ effect of different chemicals, research on which remains limited.

And then there are antibiotics, which, for modern factory farms, are wonder drugs. They make animals grow faster — although science doesn’t yet understand exactly how it happens, animals grow up to 10 per cent quicker when fed food laced with antibiotics — without changing the composition of the meat.

>>> How to use strength training to boost your cycling

In intensive farms, where animals are housed closer together in less healthy conditions, so-called ‘sub-therapeutic’ levels of antibiotics reduce the incidence of animal illness.

In less euphemistic terms, when thousands of chickens are housed feather to feather in total darkness, antibiotics allow farmers to meet the demand for cheap meat: more chickens, more quickly, for less money.

“My chickens cost me £2.80 just to kill, and they live for 100 days,” explains Scheckter. “You can go to a supermarket and buy a whole chicken for £2, which has grown from egg to chicken in 36 days.

“Maybe 90 per cent of the people won’t know the difference, and won’t want to know the difference. But from a financial point of view, I don’t get a lot of joy from the supposed good value.”

>>> Listen to your body: don’t ignore the warning signs of injury

The biggest risk to consumers from these practices is the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, a threat so grave that medical professionals warned earlier this year that it could plunge medical science back into the dark ages.

When used at sub-therapeutic levels, antibiotics kill off weak bacteria but allow resistant bacteria to thrive. Data is limited, but nearly 45 per cent of the UK’s antibiotic consumption goes to farming.

Whereas organic and biodynamic farms limit antibiotics to genuine animal illness, conventionally farmed cows, chickens, pigs and sheep continue to be fed antibiotics that are critical to human medicine, potentially leading to strains of resistant superbugs.

Steroid stakes

Cyclists these days tend to become quite clued-up amateur pharmacists, almost by accident, and if there’s one drug in particular (besides EPO) that we’ve become aware of, it’s clenbuterol.

A steroid that can increase aerobic performance in athletes, clenbuterol is mainly used in farming to promote muscle growth and fat loss in animals. Alberto Contador’s tainted steak excuse wasn’t believed by his anti-doping tribunal; his team-mate Michael Rogers deployed the same excuse and it worked.

>>> Four pro training drills to get you riding faster (video)

Both riders tested positive for traces of clenbuterol in competition; Contador during the 2010 Tour de France and Rogers during the 2013 Japan Cup shortly after competing at the Tour of Beijing.

The Australian claimed he had eaten contaminated meat in China and, because the drug is indeed used in vast quantities by Chinese farmers, Rogers was let off. Contador, whose steak allegedly came from a butcher in Spain, was deemed culpable.

In fact, in 2012 the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) warned athletes competing in Mexico or China to eat only in restaurants approved by the event organisation. In January 2014, the Union Cycliste Internationale warned riders not to eat meat in those countries at all.

>>> Can delayed onset muscle soreness be avoided?

“I’d be on a vegetarian diet if I returned [to China],” Rogers said in 2014. Steroids are banned in British and European farming but allowed in many countries, including the USA. While you shouldn’t find clenbuterol in American cows, you may find traces of other steroids, including recombinant bovine growth hormone and testosterone.

Besides the issue of anti-doping, there remain unanswered questions about the impact of steroids on human health and the wider environment.

>>> Detraining: The truth about losing fitness

That’s why many professional teams now ensure their meat is traceable back to its source — it wasn’t without a touch of irony that Saxo-Tinkoff trumpeted the arrival of an official Italian beef supplier in 2014.

Will I ride faster?

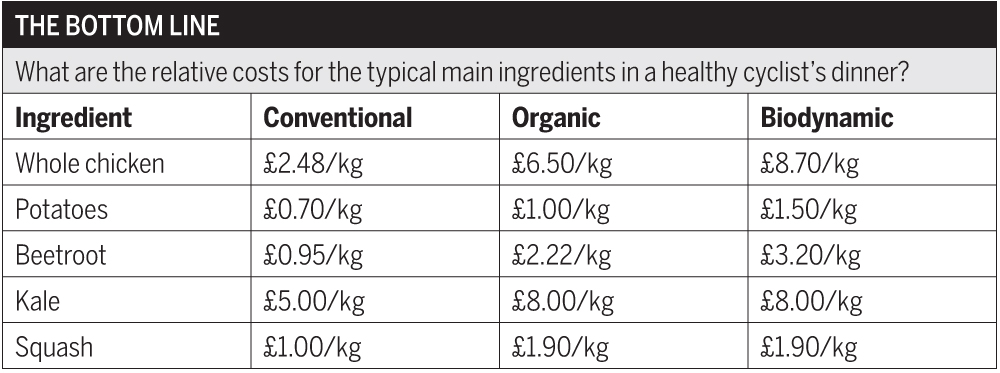

These are serious concerns, but is food produced to special standards such as organic or biodynamic really worth the substantial additional outlay?

“Although there is evidence that organic and grass-fed produce has fewer pesticides and higher levels of antioxidants and omega-3, we don’t know if this truly makes a difference to health,” says dietitian Laura Tilt.

>>> How to ride faster up short, steep hills (video)

“Put simply, there aren’t any long-term studies showing that organic food reduces the risk of disease or improves performance. For most cyclists, simpler changes to diet such as cutting down on alcohol or eating more vegetables are likely to have more impact than switching to organic or biodynamic.”

Scheckter acknowledges that performance benefits are difficult to prove: “It’s very difficult to say that by eating this biodynamic food I’ll take a second off my time. Food is so long-term. I can’t say if you eat this you’re going to sprint better, but I think if you’re a top athlete you want to do everything you can to make yourself better. I think great food, good natural healthy food has got to be your fuel.”

>>> How to tell whether you are overtraining, and how to avoid it

In many respects, biodynamic food doesn’t differ vastly from organic; it’s the Dura-Ace to the Ultegra — organic may lack some of the top-end status but in essence it’s just as effective. Biodynamic’s trump card over organic is welfare and sustainability; next time you see a corn-fed organic chicken in your supermarket, for example, bear in mind that chickens are omnivores and would not naturally eat only corn.

In the final analysis, the biggest gain to be had from biodynamic and organic produce may come down to your sense of having made the best possible choices for your body, for animals and for the environment — the faith that what’s on your plate is as untainted as it possibly could be.

What do food labels say about the food you’re buying?

Biodynamic

Look for: Demeter label

Produced from biodynamically certified farms managed as self-sustainable ecosystems. Limits on artificial inputs and animal welfare standards are both stricter than organic.

Freedom food

Look for: Blue and white logo

Produce adheres to minimum standards of animal welfare set and regulated by

the RSPCA. It doesn’t necessarily mean free-range, and produce is not raised to organic standards.

Organic

Look for: Black and white Soil Association logo

The Soil Association certifies over 80 per cent of British organic produce. There are strict limits on synthetic chemicals used in farming and standards of animal welfare are higher than legal requirements.

Red tractor

Look for: Red tractor logo, sometimes with a Union flag

Produce conforms to standards set by Assured Food Standards, which are very similar to the legal minimum standards for conventional production in the UK. The Union flag means produce comes from Britain. The organisation Compassion in World Farming argues this does not always represent high welfare standards.

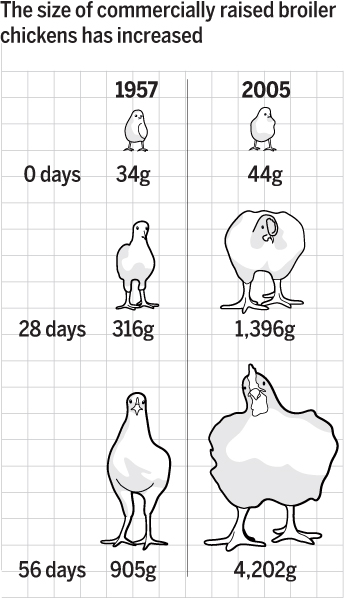

The changing shape of chicken

The animals we are eating today are very different beasts to those eaten by our grandparents, and even our parents, a matter of decades ago.

The typical modern broiler chicken farmed intensively for meat can now grow from egg to slaughter in just 36 days — a third of the time it takes for a chicken raised outdoors on a biodynamically certified farm. Many broiler hens spend those 36 days indoors in total darkness.

Thanks to selective breeding, and without taking into account the liberal use of hormones and antibiotics in some countries, chickens at 56 days old today are more than four times bigger than they were 60 years ago, weighing on average 4kg, according to research from the University of Alberta in Canada. They end up looking bizarrely top-heavy, like body builders who’ve skipped leg workouts — such is the demand for cheap breast meat.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Richard Abraham is an award-winning writer, based in New Zealand. He has reported from major sporting events including the Tour de France and Olympic Games, and is also a part-time travel guide who has delivered luxury cycle tours and events across Europe. In 2019 he was awarded Writer of the Year at the PPA Awards.

-

'This is the marriage venue, no?': how one rider ran the whole gamut of hallucinations in a single race

'This is the marriage venue, no?': how one rider ran the whole gamut of hallucinations in a single raceKabir Rachure's first RAAM was a crazy experience in more ways than one, he tells Cycling Weekly's Going Long podcast

By James Shrubsall

-

Full Tour of Britain Women route announced, taking place from North Yorkshire to Glasgow

Full Tour of Britain Women route announced, taking place from North Yorkshire to GlasgowBritish Cycling's Women's WorldTour four-stage race will take place in northern England and Scotland

By Tom Thewlis

-

'We've talked to literally hundreds of brands' - Ineos Grenadiers CEO gives update on sponsor hunt

'We've talked to literally hundreds of brands' - Ineos Grenadiers CEO gives update on sponsor huntTeam boss John Allert says there have been 'fabulous rumours' about new partners

By Tom Davidson

-

'A stage win in the Tour de France really changed my profile': Steve Cummings on working as a chef, idolising Michele Bartoli, and playing football like Trent Alexander-Arnold

'A stage win in the Tour de France really changed my profile': Steve Cummings on working as a chef, idolising Michele Bartoli, and playing football like Trent Alexander-ArnoldJayco-AlUla Sports Director discusses his most significant career victory and how he got into cycling

By Tom Thewlis

-

Tom Pidcock to remain 'part of the Pinarello family' after joining Q36.5 Pro Cycling

Tom Pidcock to remain 'part of the Pinarello family' after joining Q36.5 Pro CyclingBritish star will continue to ride Pinarello bikes after leaving Ineos Grenadiers

By Tom Thewlis

-

Ineos Grenadiers hire new head of engineering as reshuffle continues

Ineos Grenadiers hire new head of engineering as reshuffle continuesFormer British Cycling lead, Dr Billy Fitton, is the latest of a handful of new appointments within the British squad

By Tom Davidson

-

Overachiever: Cameron Wurf competed in the Amstel Gold, La Flèche Wallonne and an Ironman, all in just eight days

Overachiever: Cameron Wurf competed in the Amstel Gold, La Flèche Wallonne and an Ironman, all in just eight daysCameron Wurf is both a member of Team Ineos Grenadiers and an accomplished professional long course triathlete who has racked up numerous World Tour and Ironman race finishes across his career.

By Kristin Jenny

-

‘I feel lucky to be alive’: Magnus Sheffield speaks for the first time about Gino Mäder’s fatal crash

‘I feel lucky to be alive’: Magnus Sheffield speaks for the first time about Gino Mäder’s fatal crashThe American describes what he saw at the Tour de Suisse, eight months after the tragedy

By Tom Davidson

-

Tom Pidcock: Tour of Britain route 'not really ideal for me'

Tom Pidcock: Tour of Britain route 'not really ideal for me'Brit says he wants to win home stage race, even if the course plays in Wout van Aert's favour

By Tom Davidson

-

This 39-year-old INEOS Grenadiers rider moonlights as a pro triathlete

This 39-year-old INEOS Grenadiers rider moonlights as a pro triathleteA Jack of all trades, Cameron Wurf is a domestique for INEOS Grenadiers professional cycling team, but doubles as a successful pro triathlete.

By Kristin Jenny