Between a clock and a far place: The golden era of long-distance record breaking

Long-distance record breaking may have declined in recent years, but epic feats of endurance such as the End-to-End continue to exert a hold on the imagination, finds James Shrubsall

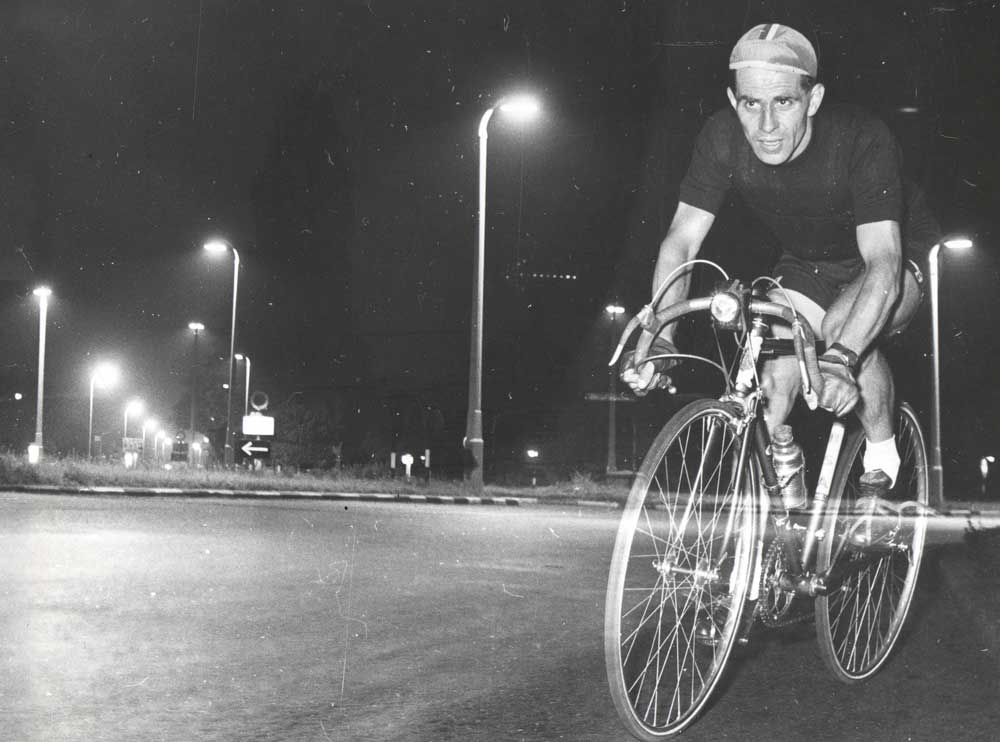

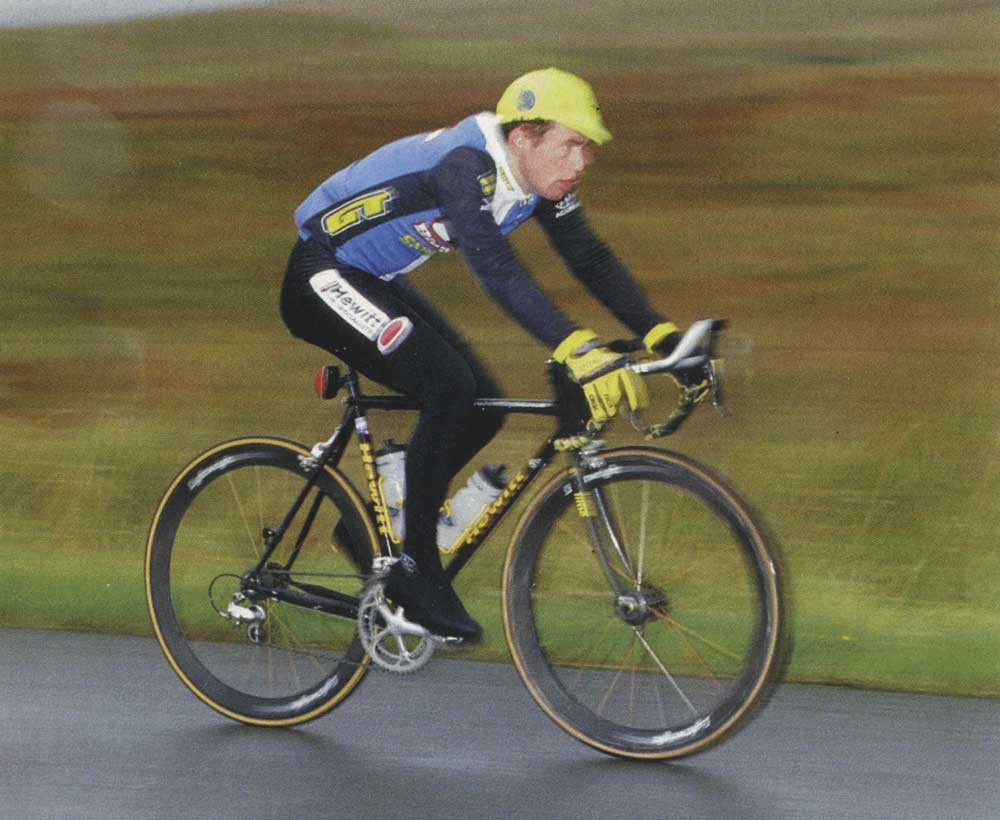

Bob Maitland (CW Archive)

On a dark September night in 2001, up in the northern reaches of Scotland’s Cairngorm mountains, a persistent rain is spatting off the tarmac of the main A9. In the distance, the twin headlamps of a vehicle approach, moving at a shade over 20mph, its lights twinkling on the wet tarmac. Just ahead of it, a dark shape, its own front light now visible, can be made out. As the mini convoy gets nearer, the shape becomes a cyclist, riding on tri-bars and aero wheels.

As he passes, ticking over at a metronomic 22mph, Gethin Butler’s sunken face tells the story of the gruelling 700-mile journey to get here — one which will only finish 300 miles later after he has set new Land’s End to John o’ Groats and 1,000-mile records.

>>> Going the extra miles: how to train for and complete an ultra-distance sportive

This is place-to-place record breaking, and this ride, the End-to-End, is only the tip of the iceberg.

Place to place is a branch of the sport with a rich heritage, from young trailblazers like George Pilkington Mills — who covered the 840 miles from ‘corner to corner’ in a touch over five days on a penny farthing in 1886 — to Butler’s meticulously planned, modern-day romp into the record books.

Butler’s is one of only two men’s ‘LEJOG’ bicycle records in the last 35 years, although there have been attempts since — only last month Dutchwoman Jasmijn Muller had

to abort her effort after falling ill halfway through.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But back in Mills’s day it was all the rage. In the 20 years following his penny farthing ride, the record fell 13 times.

The End-to-End may be La Doyenne of place-to-place record setting, but an extended family of dozens more, some more obscure than others, are scattered around the country. Of these, the more prized accomplishments like London to Brighton and Back and London to Bath and Back aren’t so far behind. Winchester to Canterbury on the other hand, or Lancaster to York and Back, might be less celebrated and even less hotly contested — the latter was last broken in 1954 — but they are there for the taking for anyone with the fitness and the inclination.

Joy v Maitland

The origins of road record breaking lie not simply in noble physical endeavour, but in commercial gain too, and it wasn’t always done by the book.

“If you wind the clock back 100 years, it was professionals doing the rides to get publicity for manufacturers,” explains Road Records Association (RRA) committee member and 39-time record holder Ralph Dadswell. “The organisations that existed before the RRA and then became the RRA were very much there to stop frivolous claims by manufacturers. If they gave a nod to a ride, it meant it had been done properly, and there was no jumping on the train or whatever, because these things did happen.”

A deep enthusiasm for road records, despite a pause for the First World War, lasted all the way up to the Second World War at the end of the 1930s.

The men’s bicycle London to Brighton and Back, for example, was broken 30 times between 1890 and 1935, and only six times in the 82 years since — the last being top British domestic rider Phil Griffiths in 1977. It was a similar story with Land’s End to John o’ Groats, which fell 16 times up to 1937 and only eight since then.

Up to this point the sport had not so much been male-dominated as jealously guarded, with women allowed barely a look in. But in 1935 they were finally recognised in their own right with the inauguration of the Women’s Road Records Association.

Fifty years of oppression had seen female place-to-place aspirants criticised in the press for even trying and their efforts go unrecognised, at least officially. There had even been an 1892 decree by the RRA for its officials to “refrain from timing or in any other way assisting” women in their record attempts.

But nearly 50 years later, the political landscape had changed, and it was clear that women weren’t about to hang up their racing wheels. The WRRA was duly formed and on June 25 Lilian Dredge set out into a headwind from Land’s End to London to set the first record of a new era that, following the Second World War, quickly blossomed into a thriving scene with stars of its own (see panel).

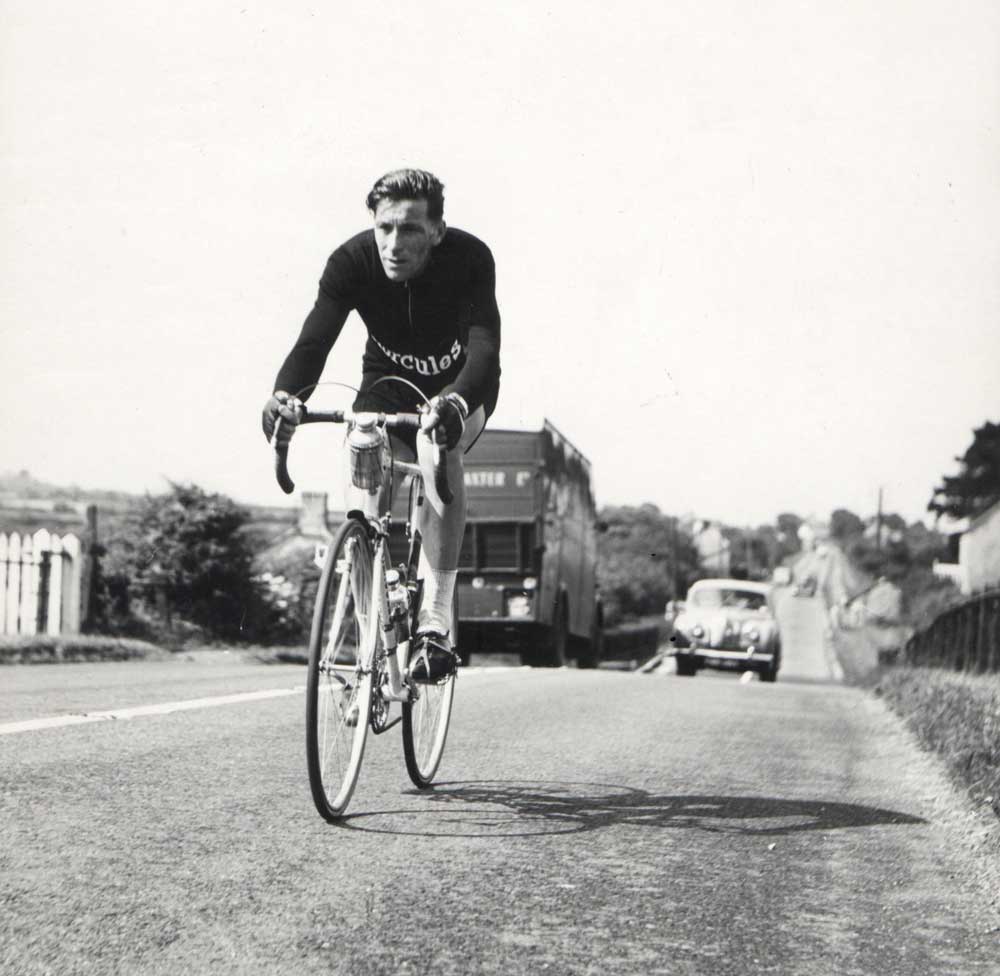

Back in the men’s camp, place-to-place record breaking woke from its wartime slumber with a spring in its step, bursting into life thanks to a trade team rivalry between Ken Joy of Hercules and BSA’s Bob Maitland (main pic).

Between October 1952 and September 1954 this virtuoso pair set 13 new records between them, often seeming to focus on records the other had set. Joy and Hercules eventually ended up having the final say — after Maitland had succeeded in taking four minutes off Joy’s Liverpool-Edinburgh record, Joy reduced Maitland’s new time by 10 minutes only 18 days later, bringing the curtain down on the whole intoxicating affair.

Only now did the business of breaking national records settle into something of a lull, as Roy Green notes in his book 100 Years of Cycling Road Records: “Not surprisingly, there were few challengers for most of the bicycle records for some years after this famous two-year duel.”

Over the decades since, the history books show that men’s place-to-place record breaking was never again as prevalent as it had been. Perhaps that was due to fashion, perhaps down to the burgeoning popularity of road racing in the UK. It might even be that after Maitland and Joy’s little tête a tête, many of the records were now seen as unbeatable, and the enthusiasm waned.

But it was far from dead. Talented riders would pop up every decade or so and lay down a new mark, a trend that continued more or less to the present day.

Highway to hell

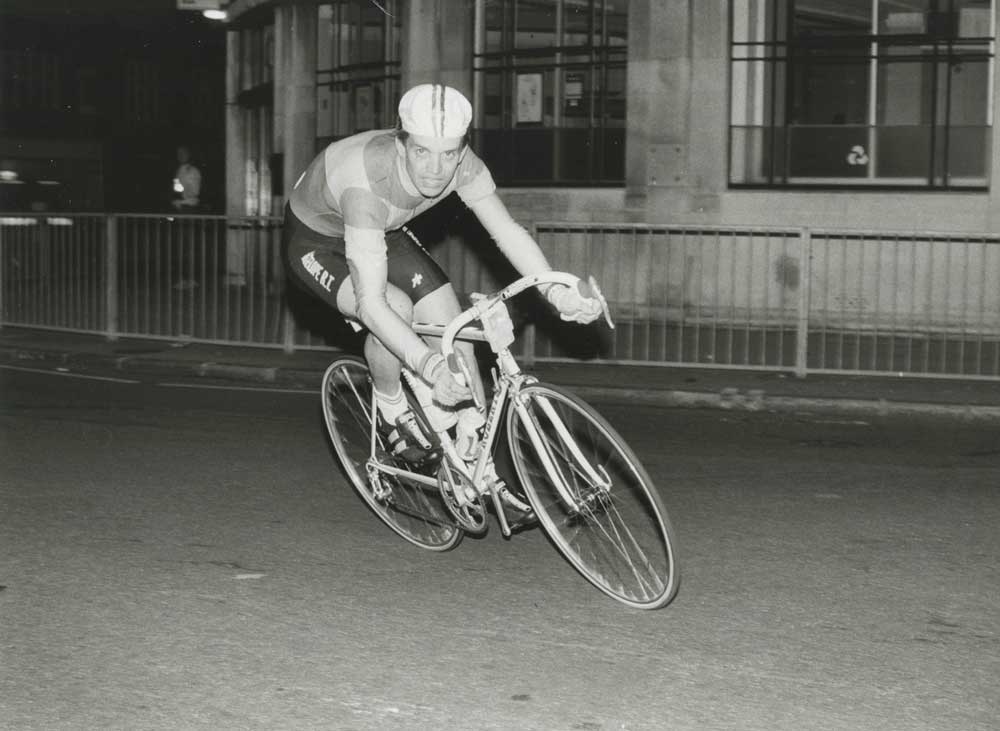

One of the more recent protagonists is affable Hampshire son Glenn Longland — holder of six current place-to-place records spanning 19 years between 1979 and 1998, as well as the RRA 12-hour record and the rather more esoteric 50-mile tandem tricycle record, set with Dave Pitt.

Longland’s laid-back character is perfectly exemplified by the way he came to set his first ever record.

“The first one, I did it for charity. It was Southampton to London and Back in October ’79, I can remember all the dates, I’ve still got all the trophies. It just went from there really,” he says. “Ralph Dadswell looked after me, told me when the wind was blowing the right way, and that was just it, I just used to go.”

He tells it like it almost happened by accident, but Longland, now 62, is clearly a driven individual, as is a prerequisite for anyone willing to put themselves through the long hours of suffering involved in place-to-place endeavours.

Longland describes “going through hell”, while Gethin Butler said he felt “deadened” following his LEJOG record. This is compounded, says Dadswell, by the mental strain of what is a win or lose situation: “Sometimes, there’s that point when you realise that things are getting a bit tight, and if you don’t find some more speed, then you and your helpers needn’t have bothered getting out of bed that morning.”

But for all the hardships, place-to-place riding can clearly get addictive, because so many aspirants just keep coming back for more. “It’s a bit more interesting than your average time trial,” says Dadswell, whose many tricycle records are a case in point. “Sometimes I think people quite like doing time trials and just see this as something slightly different but using the same skills.”

The lure of the End-to-End in particular, is easy enough to explain: “People see that as a recognisable thing to have done,” Dadswell says. “It’s more difficult to talk about some of the smaller records because no one’s ever heard of them — I mean, I’ve got a record from Purley to Eastbourne and back which I’m desperately proud of, but on the other hand nobody cares! While Lands End to John o’ Groats is something that everyone in a strange way can identify with.”

Longland says that for his part, riding road records simply came as part and parcel of being a bike racer: “We would do everything,” he recalls. “Promote events as well as racing and not just set your mind on one thing — time trials, road racing, record attempts. I even won the divisional kilometre track championship,” he chuckles. “That’s what we did.”

Bayton's barnstormer

Place-to-place records seem to have the right ingredients — the romance of an adventure coupled with physical challenge — but these days, participation has dropped off substantially. In fact, the most recent national bicycle record on the RRA’s books — the coast-to-coast Pembroke to Great Yarmouth — was set back in 2004 by Marina Bloom. Has riding hard into and out of city centres become less attractive as traffic and dual carriageways have proliferated?

“Roads have changed, traffic’s changed,” concedes RRA general secretary Brian Edrupt. “That might have something to do with it.”

But Edrupt’s own theory is that it’s a “generational thing” and explains that those whose rides necessitate a ‘turn’ in London will begin their attempts several miles out of the city in the early hours, race straight in and out again to complete that section while traffic’s relatively light.

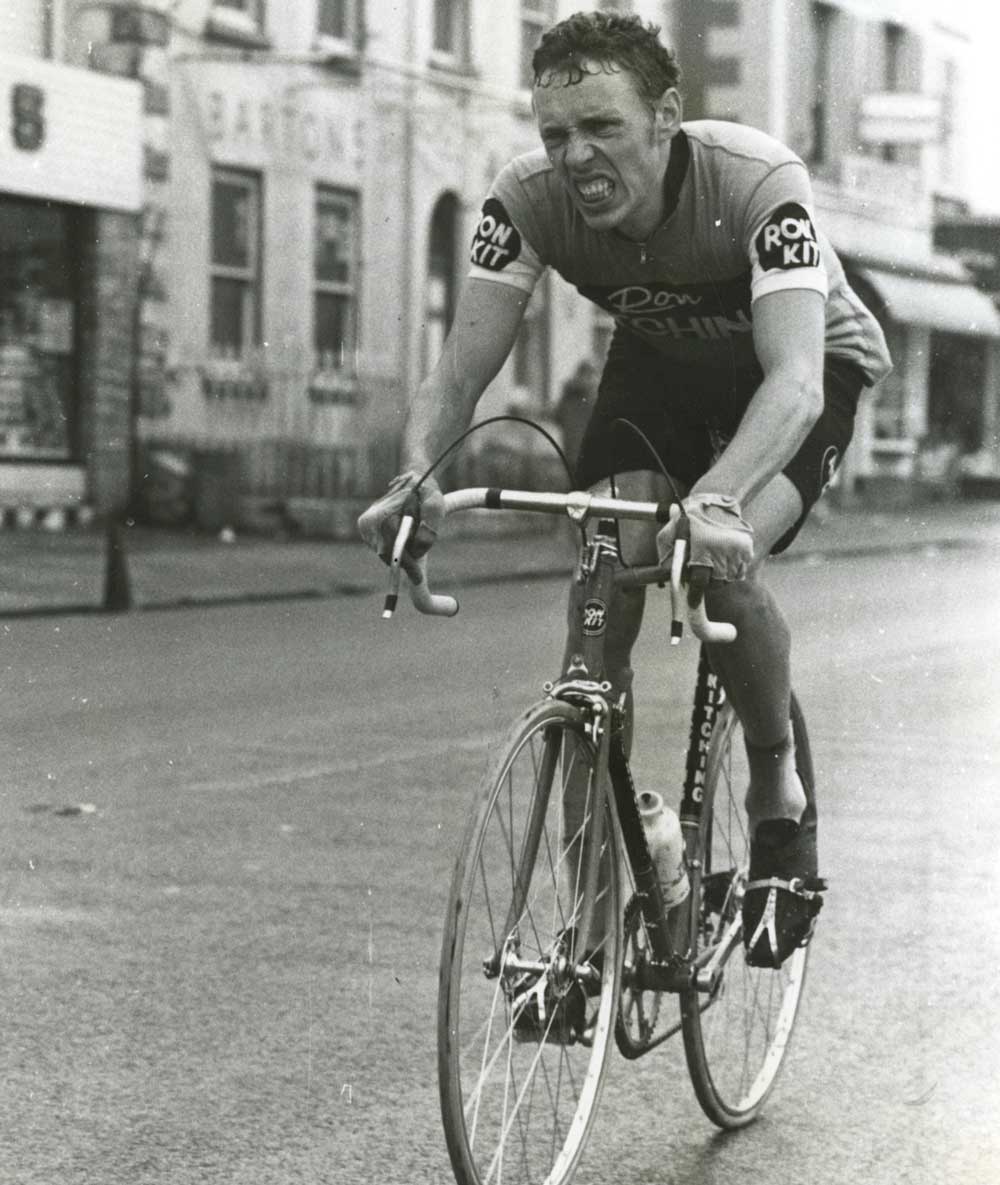

“But you can’t say the records aren’t beatable,” Edrupt says, and Dadswell largely agrees, though warns that some are harder propositions than others, such as British pro Phil Bayton’s “epic” 4:19.14 from Birmingham to London in 1982 that was “pulled together at the last minute”. “That record looks pretty difficult for most people to even think about beating,” says Dadswell.

New challenges

The RRA isn’t all about revisiting old records. With a view to encouraging new blood, the association recently introduced a series of five new circuit records around National Parks — Bodmin Moor, Brecon Beacons, Cairngorms, Yorkshire Dales and Northumberland. Each has a ‘standard’ time which needs to be beaten in order to set down a recognised record, which says Dadswell, “are calculated to be not so hard that it would put you off, but not so easy that someone who wasn’t taking it seriously could do it.”

With no need to navigate major cities and the added practicality of starting and finishing at the same point, the National Park circuits have obvious advantages over traditional place-to-place challenges: “For the circuit records,” says Edrupt, “if you live nearby you could just get your bike, go down the garden path and then start. You’d only need one timekeeper and possibly an observer — you wouldn’t need two or three of each.

“I don’t think the newer lot know anything about it,” adds Edrupt, who admits the RRA could do more to publicise itself.

But rather than being a club with regular rides and engagements, the association is more a simple framework to facilitate record rides; as Dadswell says, “we have to sit here and wait” for new hopefuls.

But from my experience you won’t meet a more passionate bunch than those involved with the RRA, and they welcome new riders with open arms and plenty of good advice.

Dadswell: “If you’ve had a year or two of doing time trials and a few road races and someone says ‘record attempt’... all you’ve got to do is turn up and blast along and get some applause from people by the roadside — it’s fun to do.”

Pioneering Women

For women, gaining recognition for their physical endeavours was a road almost as long and arduous as a Land’s End to John o’ Groats attempt. Pioneers like Tessie Reynolds and Maggie Foster did undertake timed place-to-place rides as early as the late 1800s, but they were derided or at best roundly patronised by any man who cared to voice an opinion.

But by 1935 and the advent of the WRRA, women were newly empowered, and they seized the place-to-place bull by the horns.

By the time war broke out in 1939, women had set their own marks for all the major records including Land’s End to John o’ Groats, thanks to luminaries such as Lilian Dredge, Flossie Wren and Marguerite Wilson, who had joined Hercules Cycles to become the first full-time female pro of the age.

Following an inevitable wartime pause, proceedings restarted in earnest among the women, during an era John Taylor calls ‘the golden post-War years’ in his history of the WRRA.

The relatively low profile of women’s cycle sport during the 20th century means many of the names are only familiar to the aficionado these days, but one in particular stands out in the memory for a string of accomplishments that held cycling fans rapt — male or female.

Eileen Sheridan set her first road record — London to Birmingham in 5hr 22min — in 1950. A week later she set a new mark for London to Oxford, and the following year she became a professional road record breaker after being signed by the Hercules Cycles team. Sheridan quickly amassed record after record, only stalling at record number eight, when she was disqualified after riding from Land’s End to London in a new best time of 16hr 45min 47sec for breaking the WRRA’s ‘no prior publicity’ rule.

By 1954 Sheridan was ready to lay down a time for the prestigious Land’s End to John o’ Groats — success here would mean she’d broken every WRRA place-to-place record in the book. She duly obliged and, just to underline the respect she enjoyed, Hercules ran a full-page front cover ad in this magazine’s July 15, 1954 edition. “The seven stars of British cycling ride Hercules,” it announces proudly, with Sheridan taking pride of place at the top of the page, with the caption “Britain’s Greatest Cyclist”.

Sheridan wrapped up her professional career at the end of the year, but her time (it wasn’t beaten for 36 years) and her legend, lives on. In fact Sheridan herself, now 93, lives on, still a fine and active ambassador for women’s cycling.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

After cutting his teeth on local and national newspapers, James began at Cycling Weekly as a sub-editor in 2000 when the current office was literally all fields.

Eventually becoming chief sub-editor, in 2016 he switched to the job of full-time writer, and covers news, racing and features.

A lifelong cyclist and cycling fan, James's racing days (and most of his fitness) are now behind him. But he still rides regularly, both on the road and on the gravelly stuff.

-

Trek, State and Specialized raise bike prices while other brands limit US releases — Is this just the beginning?

Trek, State and Specialized raise bike prices while other brands limit US releases — Is this just the beginning?As tariffs hit, the bike industry is forced to adapt, whether through price increases, limited releases, or a restructuring of supply chains

By Anne-Marije Rook

-

How I got my non-cyclist friend hooked on riding bikes — and how you can, too

How I got my non-cyclist friend hooked on riding bikes — and how you can, tooWith a little bit of gentle guidance, “bikes aren’t my thing” can turn into “when’s our next ride?”

By Marley Blonsky