50 years since Vin Denson's historic 1966 Giro d'Italia stage victory

Vin Denson was the first British rider to win a stage of the Giro d'Italia, 50 years ago

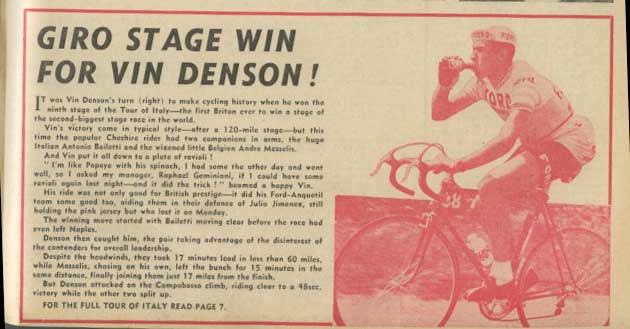

Vin Denson after winning a stage of the 1966 Giro d'Italia

In 1966 Vin Denson made cycling history when he became the first Briton to win a stage of the Giro d'Italia. But he also earned himself a dodgy headline in the Italian press - "Denson's drug is a plate of ravioli"!

That joke came after Denson had blagged a second helping of pasta by promising he’d win the following day's stage. We relive Denson’s triumph with this extract from his acclaimed autobiography, Full Cycle.

Denson’s Giro off to “rotten” start

The race started in Monaco and all the teams were invited to a reception at the palace. We were all introduced to Prince Reinier and Princess Grace. She remembered Shay Elliott from when he’d finished third in the Grand Prix of Monaco some years earlier, and with the Irish connection as well, we were there talking for ages.

With Jiménez winning the second stage, we found ourselves with the pink jersey far sooner than we expected, and it was then that I found out just how passionately partisan the Italian fans are. It was their race and they didn’t want anyone but an Italian from an Italian team to be leading it.

>>> Giro d'Italia: Latest news, reports and info

On the flat stages I had to ride on one side of Jiménez with another Ford rider on the other to protect him, because you didn’t know what they might do.

The day we went into Napoli a small group containing one of the top Italians had got away, and we had to try and bring them back to protect Jiménez’s lead. I drew the short straw and was on the front riding eyeballs out.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

We got into Napoli and were going down through the old dock area, where the streets are really narrow, and the Italian spectators were standing on their Romeo and Juliet balconies and pelting us with the contents of their rubbish bins. We held on to the pink jersey but I ended up covered with old damp spaghetti, tomato juice and banana skins. I must have stunk.

We stayed in a really high-class hotel that night and I’ll never forget the look on the doorman’s face when he went up in the lift with me. I was standing there gently humming with all this rotten food on me, and he kept trying to hold his breath or tilting his head upwards to get some fresh air.

Another plate of cappelletti

That night, for our meal, we had some really delicious cappelletti. It’s a speciality of the area - a kind of ravioli with pieces of meat and herbs and a little cap on it - and I wolfed down a plateful and told Raphaël Geminiani that if he’d get me another plate of it I’d win the stage for him next day. I wasn’t serious. I just wanted another plate of this delicious pasta, but Geminiani got up and fetched me another full plate.

Next day the stage got going and I saw a sign indicating that there was one of the mid-stage sprints coming up. I was lying fifth or sixth in that classification, so I attacked and Toni Bailetti and a Belgian called André Messelis came with me.

After the sprint we kept going. They were both in good teams - Bailetti with Bianchi and Messelis riding for Mann-Grundig - so with their team-mates and Ford France blocking, we soon made progress.

That’s something you don’t often see these days. God knows why, but blocking seems to be a lost art; everybody gives in to the sprinters’ teams when they want to pull back a break.

You have three or four men in a break, none of whom has any influence on the general classification, and each of them has half a dozen team-mates, so why aren’t there one or two from each of those teams at the front, messing the sprinters’s teams about? You rarely see it.

Perhaps it is considered too dangerous nowadays, with a larger peloton traveling at higher speeds, but you don’t have to ride dirty: if they elbow you out, drop back a bit and come round the outside and bum your way in again. After all, the sprinters’ teams do it.

Anyway, Bianchi, Mann-Grundig and Ford-France knew how to do it because the time checks kept coming over to us: three minutes, four, then five and I began to think, “Hey, we’re going to be alright here.”

We were gradually climbing from sea level up to Campobasso, a small town in the mountain range that runs right down the spine of Italy. It wasn’t all climbing; the road was undulating, but we were steadily gaining altitude.

I looked at my stage route card and saw that there were two sharp climbs before the finish, one with 40 kilometres to go and one at 25. I thought I’d test them on the first one then have a real go on the second.

I knew my attack must be decisive

They brought me back quite quickly on the first, but I was determined to get them on the second. I was still feeling good; I was eating well and I knew I was in good form. I knew I could win if I made the right move in one go, but I knew I had to make it in one go.

I had to drop Bailetti, especially, because I knew he had a bit of a sprint on him and, anyway, they’d both started swinging the lead a bit, not coming through to take their turn on the front. On the second hill I changed up a gear in readiness, and then dropped back behind them, making out I was taking a drink.

I didn’t take a drink; I dropped the bottle instead, which distracted them, and then I attacked. Boy, it hurt. The climber, little Messelis, came very close; he was about 100 yards off me at one time, and I must have had half a kilometre to go to the summit.

>>> Brits in the Tours: From Robinson to Froome

My legs were nearly breaking and I was tempted to get back into the saddle and change down to a lower gear. but I thought about the kids back home and said to myself, “Come on, Vin, you’ve got to do it for them.”

At the top of the climb I checked behind and I had about 100 metres, and the two of them had split. I didn’t look back again. I went down the descent like a stone, then on to the steady drag up to the finish.

It was a bit stiff but shortly before the finish a motor-bike came alongside and the rider gave me the news I wanted to hear: I had a 20-second advantage. ‘Well, don’t ease now,’ I said to myself. ‘Give it more.’ In the end I won by 44 seconds from Bailetti, and didn’t it feel good and wasn’t I relieved to get over the line. I still feel good about that - the first Briton to win a stage of the Giro.

Geminiani, or one of the team, must have told the story of me promising to win the stage if I could have another plate of pasta, because the next day’s Gazzetta dello Sport carried the headline ‘La droga de Denson è un piatto di ravioli’ [Denson’s drug is a plate of ravioli].

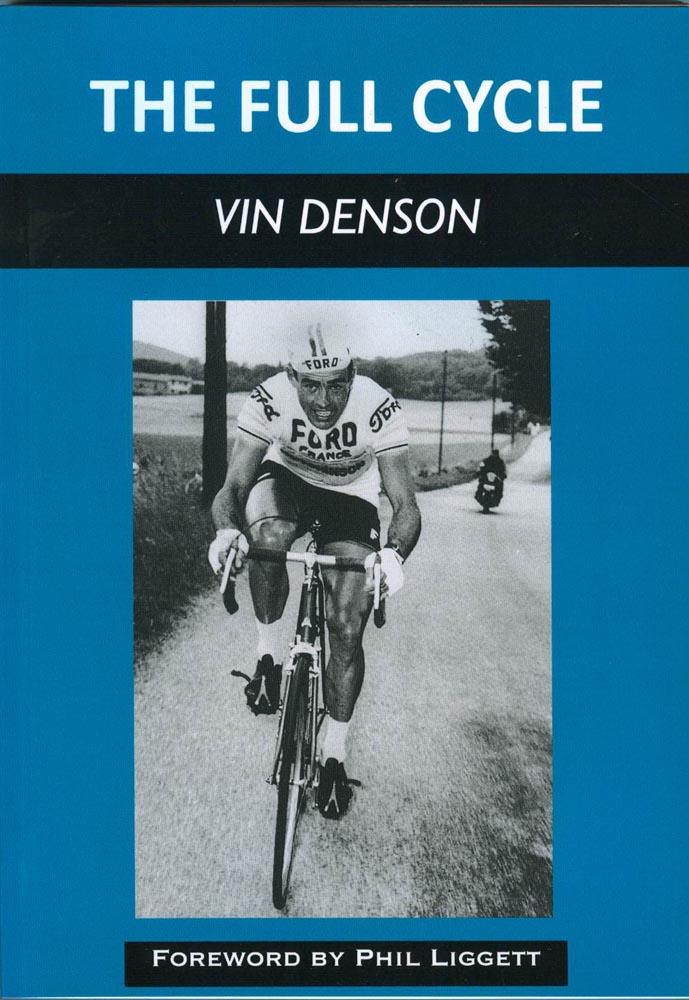

Full Cycle

by Vin Denson, is published by Mousehold Press. £12.95.

Available from: www.mousehold-press.co.uk, Mousehold Press, Victoria Cottage, Constitution Opening, Norwich, NR3 4BD. And from Sport and Publicity, 75 Fitzjohns Avenue, Hampstead, London NW3 6PD.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Nigel Wynn worked as associate editor on CyclingWeekly.com, he worked almost single-handedly on the Cycling Weekly website in its early days. His passion for cycling, his writing and his creativity, as well as his hard work and dedication, were the original driving force behind the website’s success. Without him, CyclingWeekly.com would certainly not exist on the size and scale that it enjoys today. Nigel sadly passed away, following a brave battle with a cancer-related illness, in 2018. He was a highly valued colleague, and more importantly, an exceptional person to work with - his presence is sorely missed.

-

Giro d'Italia rider almost wiped out by goat: 'Albania's great – just watch out for the goats!'

Giro d'Italia rider almost wiped out by goat: 'Albania's great – just watch out for the goats!'Dion Smith of Intermarché-Wanty confirmed it was the first time that a goat had tried to knock him off his bike.

-

Mads Pedersen reclaims pink jersey after second Giro d'Italia sprint win on stage 3

Mads Pedersen reclaims pink jersey after second Giro d'Italia sprint win on stage 3Former world champion edges out Corbin Strong, with Orluis Aular third