Flanders unravelled: a cycling guide

The Tour of Flanders is a race steeped in cycling history but it has a route that can often seem like a riddle come race day in early April; Paul Knott headed out to Belgium in an attempt to solve it - Photos by Daniel Gould

"If you’re going to do a Flemish ride, you’ve got to do it in proper Flemish weather.” Former British national champion Tim Harris’s words feel a tad extreme as the Tour of Flanders probably hasn’t taken place in the ‘Beast from the East’ conditions that we were being treated to on this late February morning.

But to hear Harris — a long-time resident of the area thanks in part to his links with the Dave Rayner Fund — say that he has never ridden in colder weather isn’t a surprise as weather reports suggest we braved conditions that ‘felt like’ minus 15°C.

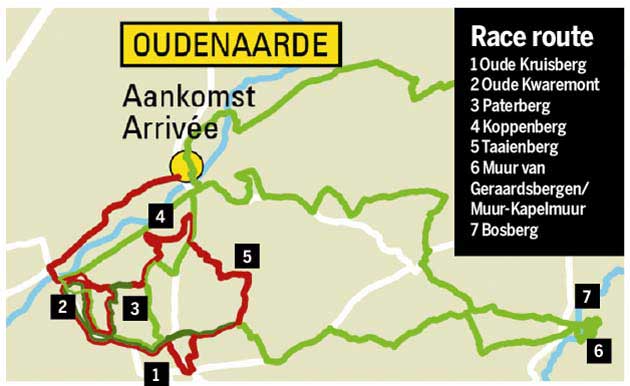

Amateur weather reporting aside, Harris is here to help unravel the route of De Ronde Van Vlaanderen or the Tour of Flanders. Its Belgian name is just as tricky to pronounce as the route is to deconstruct and conquer. The ever-changing course, labyrinth-like roads and combinations of climbs can make the parcours confusing to the uninitiated Flanderian.

Making sense of where the pinch points come, the bergs that crack the peloton and just what it’s like to conquer these iconic climbs is the aim of our venture out into the bitter weather.

The One-Two-Three punch

The three climbs of Oude Kruisberg, Oude-Kwaremont and Paterberg have been pivotal in breaking the Tour of Flanders race apart in recent history.

It is probably not a coincidence that they are the final three cobbled climbs the riders have to face in the current Tour of Flanders route since race organisers tweaked the course from the traditional Muur van Gerardsbergen/Bosberg finish in 2012.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Their notoriety as game- changing climbs regardless of their place was reinforced in 2017 when Phillipe Gilbert attacked on the second of three ascents of the Oude-Kwaremont, 55km from the finish.

The three brutish climbs come within 13km of each other: with only a flat 14km run in to the finish after the final ascent of the Paterberg, if you get it wrong here your chances of getting the time back are eliminated.

The Kruisberg itself isn’t a climb that usually decides the race, despite Alexander Kristoff and Niki Terpstra using it as a springboard for their two-man sprint finish in 2015.

“You don’t see many attacks on the Kruisberg because the Kwaremont and Paterberg are still to come. So you have got to have some guts to go from here,” Harris says.

Its clear to see why; the steady rise out of the town of Ronse isn’t one to break the back of most riders and as it’s our first climb of the day it feels like a pleasant warm-up. However, after 240 kilometres in the saddle it will certainly shed a few riders who have managed to hang on until this point. Not because of its brutal pitches in gradient, or energy-sapping cobbles but more due to its position at the sharp end of the race.

As we crest the Oude Kruisberg we turn off the N60b — the busiest road on our journey — and begin to cruise along the N36 which turns into a straight descent in Berchem. As we negotiate our way in and out of the cycle lanes filled with debris from trees that line the carriageway, Harris explains how the riders like to crank up the speed while descending in the run in to the climb back up the hill a few hundred metres along on far rougher terrain.

“The peloton will be riding at around 100kph down here fighting for position going into the Kwaremont,” Harris explains. “It’s crazy as there is so much road furniture at the bottom before the turn, but they know they have to be in the first 15 riders.”

Flanders climbs are known for their sharp turns immediately prior to the ascent, and just like the climbs these pinch points arrive with constant regularity.

While its accommodating average gradient may attract Flanders rookies to ride the v, as with many such climbs, a bite usually awaits on the road itself. Harris explains it’s not only the condition of the cobbles themselves, but the way they are laid on the road as to how they can influence your momentum up a climb, and when it comes to the Kwaremont it’s as gappy a hillbilly’s smile.

>>> Tour of Flanders: Latest news and race info

This is where the Kwaremont’s length comes into play, at over two kilometres the importance of maintaining power through the pedals over the smoothest route is vital. As the incident involving Peter Sagan and a supporter’s jacket in 2017 showed, pushing the boundaries of the smooth gutter can prove problematic for the pros. It’s tempting for amateurs too but this early on we’ve come to ride cobbles and so cobbles we shall ride.

It can be easy to lose momentum and go into the red on the steep section up to the village, from there on the strongest riders show their muscle to push on whereas others look to survive the remaining grind. When it comes to Harris and I, it is clear who is the seasoned cobbles rider and who is having a crash course introduction.

Even though Harris eludes to the brutal cobbled surfaces that the Paterberg posseses on our approach, the race can be decided just as much on the non-cobbled sections as the pavé.

“The centre of the road is what we call a death ridge,” Harris explains as he points to the gap between the two sheets of tarmac that split road in two.

“It’s a small enough gap to just fit a tyre in and once your wheel gets wedged in there it’s hard to get it out without coming down.”

This is exactly what happened to Sep Vanmarcke on the run in to the Paterberg in the 2017 edition of De Ronde, ending his chances of victory.

In spite of this warning, Harris suggests we ride full pelt into the base of the Paterberg to get the full “Flanders experience”. The past knowledge of the roads shows when Harris foresees the sudden kick up as the Paterberg appears directly in front of us after a right-hand turn. I have just enough blood running through my fingers to flick through the gears to a much more manageable cadence before the slog starts.

Harris’s anticipation for what is ahead sees him create a 10-metre gap before we have even started. We crawl up past a lone driveway but our slow speed means the cobbles decide where our tyres will land after each all-out-effort pedal stroke on the 20 per cent section, resulting in a fun/terrifying guessing game.

Watch highlights of the 2018 Tour of Flanders

I succumb to weaving across the road to lessen the gradient — a pleasure that the pros won’t have when climbing the Paterberg in a pack — the iconic right angled step-like fences show just how steep the relentless road is. It’s definitely skewed into a gentle rise when watching Flanders on TV.

As we crest the top of the climb, it seems the ideal point to take stock of the three back-to-back-to-back climbs we’ve just conquered. In Harris’s case its time to take a drink, “My water has frozen!”

Wary of our legs suffering the same fate, we press ahead like the pros would.

Deadly duo

In the twisting maze that is the Tour of Flanders route, the Koppenberg and the Taainberg signal the beginning of the final loop before the finish. Every climb from now on will only be ascended once, and when you consider the Koppenberg and the effect it has had on shaping the race due to the various mishaps that have taken place on it, it’s a wise decision.

Organisers notoriously banned it after Jasper Skibby came to a standstill and fell in the 1987 edition before being driven over by a race organiser’s car. The Koppenberg returned to the race 17 years later before being excluded in 2007 as the road deteriorated once again but it’s now back and remains one of the most iconic climbs in cycling.

A lone house with a red door signals another sharp right turn where the cobbles begin and the road cranks up. The ragged surface of the Koppenberg can be so vicious that it can shake your bike to one side of the road. Steep banks line the road for about 150m making the climb very claustrophobic as the leaves and mulch cover the smooth gutter line, giving us no salvation as our energy begins to sap and our cadence slows.

It is purely a case of gritting it out to make it to the top, at 20 per cent at its steepest, some of the world’s best have succumbed on Koppenberg, including three-time Flanders winner Fabian Cancellara who was forced to walk after being caught behind a crash on the narrow berg.

“It’s nearly impossible to get going again if you stop, the climb is so steep and narrow there isn’t enough room to get the momentum to start again.”

Harris’s words of wisdom ring true just as we get the top, one of us in a single machine-like effort, the other stalling halfway up and requiring a jump start from our photographer Daniel.

>>> Check out six of the key Tour of Flanders climbs on Strava

Unsure of what direction we are currently facing after cresting the Koppenberg, Harris guides us along the short eight-kilometre ride to where the Taaienberg awaits. In that short time there’s also the cobbled road of Mariaborrestraat and the climb of Steenbeekdries, which don’t really trouble the legs by comparison.

The Taaienberg climb itself is best known for being three-time Flanders winner Tom Boonen’s favourite climb in the cobbled Classics — gaining it the nickname ‘Boonenberg’. Ironically it was here where the Belgian icon’s fairytale ending came to an abrupt end on his last Flanders ride in 2017; suffering from a mechanical issue, the race charged ahead without him.

The short rise up through the trees, before a false flat drags its way to the summit, suited the Belgian rider down to the ground. This is where the hammer can be put down by the strongest riders in the peloton on the riders suffering at the back. There is a notable flat gutter up both sides of the climb and onto the false flat if you want to bail out of the cobbles. But we’re still feeling fresh enough to shrug off its advances.

The classic finish

As previously mentioned, the Muur van Geraardsbergen and the Bosberg were once the finale of Flanders for over 35 years. The iconic chapel atop the Muur van Kapelmuur — the final part of the van Geraardsbergen ascent — is one of the most famous sights in cycling and still appears in the race two thirds of the way through.

Unlike a lot of Flanders climbs ‘The Muur’ actually begins in a genuine town, climbing through the streets of Geraardsbergen on cobbles which don’t rattle the body like some of the other Flandrian climbs, but that you wouldn’t relish commuting on.

The lustre of this famous ascent is somewhat dulled with a cheesey funfair that is taking place but once out of the town as the road kicks up and the chapel appears up the hill, the distant sound of the rides disappears.

In pure numbers terms the Muur certainly holds its own, with a maximum gradient touching 20 per cent and averaging over seven per cent. It builds in intensity the further we ascend as the climb gets steeper and the cobbles become more rugged.

Thanks to the layout of the cobbles, a respite of some sort is given on the steepest part of the climb as it’s easier to skip from one cobble to the next rather that hurdling the multiple mini-roadblocks of the Paterberg and Koppenberg. This section is infamously where Fabian Cancellera attacked Tom Boonen in 2010 — the penultimate time the Kapelmuur was used in the climax of the race.

>>> 2019 Tour de France Grand Départ: Muur van Geraardsbergen and team time trial confirmed

After cresting the Muur, we head over the N495 towards Onkerzelestraat, which leads onto Brusselsestraat and into the settlement of Atembeke. The Bosberg itself now only features in Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, but it was not so long ago it was at the forefront of the finale of Flanders.

It will once again come to prominence when the Tour de France visits the Muur and Bosberg on the opening stage of the Belgian Grand Départ in 2019.

Lined with the aforementioned ‘death ridges’ in the run in, the first thing you notice is bumpy cobbled terrain of the Bosberg on a dead straight road through the woods of Kapellestraat. The uneven surface looks like it may be the most troublesome we’ve faced as we approach, but the road reveals a clear racing line where the cobbles are compact and smooth from being worn down by cars over the years.

But with many miles in the legs, and given that as you are riding this loop your body will be recovering from going into the red up the Muur, the Bosberg mustn’t be underestimated.

It is useful to note that the dead straight ascents of the Paterberg, Koppenberg and Bosberg run from west to east. So if an easterly wind is blowing it is crucial to ensure you pace your effort — that’s if you have the ability to do so and you’re not on the limit already.

As the Bosberg completes our whistle-stop tour around the Flanders region, beating the weather feels like more of an accomplishment than the climbs itself. If you plan on taking on Flanders yourself — it should be on the bucket list for all cyclists — attacking them in these duos and trios makes it possible to either easily follow the race route or plan your own variation. However, February may not be the ideal time of year to try it.

The major climbs of the Tour of Flanders

The one-two-three punch

Oude Kruisberg

Length: 860m

Elevation gain: 52m

Average gradient: 6%

Max gradient: 9%

Oude Kwaremont

Length: 2,144m

Elevation gain: 94m

Average gradient: 3%

Max gradient: 12%

Paterberg

Length: 365m,

Elevation gain: 40m

Average gradient: 11%

Max gradient: 20%

Deadly duo

Koppenberg

Length: 576m,

Elevation gain: 62m

Average gradient: 10%

Max gradient: 19%

Taaienberg

Length: 638m

Elevation gain: 32m

Average gradient: 7%

Max gradient: 15%

Classic finish

Muur van Geraardsbergen/Muur-Kapelmuur

Length: 1,109m,

Elevation gain: 90m

Average gradient: 7%

Max gradient: 20%

Bosberg

Length: 1,378m,

Elevation gain: 75m

Average gradient: 5%,

Max gradient: 11%

Flanders travel guide

How to get there: Oudenaarde is a two-hour drive from Calais. Flying into Brussels gives you the option of a 50-minute direct train into Oudenaarde.

Where to stay: La Cerveza B&B, where CW stayed, just outside of Oudenaarde which is located at the top of the Eikenberg ticks all the boxes. But any accommodation option around Oudenaarde will be a good choice if you want to rack up as many bergs as possible.

More than a bike shop: If you head out for the race itself and want to experience the cobbles, the Tour of Flanders museum is a must visit when in the region. Not only is the Centrum Ronde Vlaanderen the perfect place to learn about a legendary race — you can also rent bikes to hit the bergs yourself, with useful Flanders maps and signs to guide your way around the region. www.crvv.be

Our route on Strava: Take a look at our full route on Strava here, where you can also download a GPX file.

Cafe stop: Café de Muur is about as traditional as a Belgian cafe can get, halfway up the Muur van Geraardsbergen just as you leave the town centre. It will be very tempting to dip in for a cuppa just as the road kicks up.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Paul Knott is a fitness and features writer, who has also presented Cycling Weekly videos as well as contributing to the print magazine as well as online articles. In 2020 he published his first book, The Official Tour de France Road Cycling Training Guide (Welbeck), a guide designed to help readers improve their cycling performance via cherrypicking from the strategies adopted by the pros.

-

'I start every race to win' - Mathieu van der Poel fired up ahead of Paris-Roubaix showdown with Tadej Pogačar

'I start every race to win' - Mathieu van der Poel fired up ahead of Paris-Roubaix showdown with Tadej PogačarTwo-time winner says he has suffered with illness during spring Classics campaign

By Tom Thewlis Published

-

'It's really surreal that now I'm part of it' - 19-year-old Imogen Wolff set to go from spectator to racer at Paris-Roubaix

'It's really surreal that now I'm part of it' - 19-year-old Imogen Wolff set to go from spectator to racer at Paris-RoubaixBrit first came to see the 'Hell of the North' when she was six

By Tom Davidson Published