Icons of cycling: Fallowfield Track

An icon owned by a legend, Fallowfield Track was a cycling Mecca in the 1950s

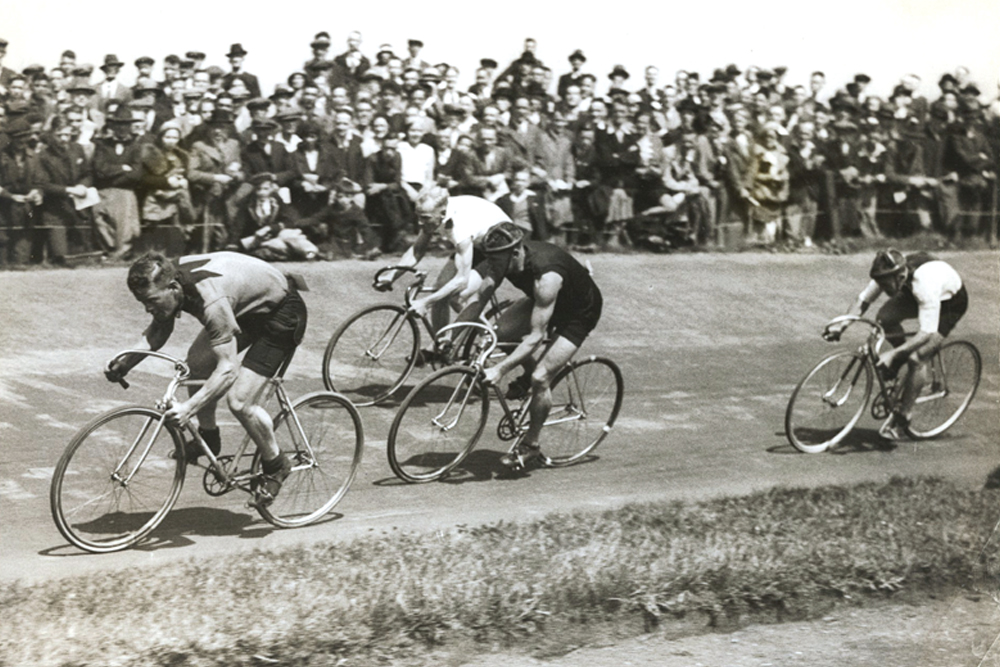

Fallowfield saw a century of cycle racing. Photo: Cycling Weekly Archive

Imagine you were a good club racer in the north of England during the 1950s. You’d be competing in time trials, and do a bit of grass-track racing. Both on a fixed-gear bike. Then, if you started making progress you would hear mentioned a magical place in Manchester.

Its name was Fallowfield and it was huge russet-coloured bowl, which by the 1950s was resurfaced with concrete. It had unfeasibly high 30-degree bankings that transitioned into pan-flat straights. To an ambitious young racer, at 509 yards round, Fallowfield would have left an unforgettable first impression.

>>> Icons of cycling: Herne Hill Velodrome

The Tuesday night track league drew in a who’s who of northern racing and major track meetings drew massive crowds to watch world-class riders. In 1955 the track was bought by a boy from Bury who went on to become sprint world champion.

For a while Fallowfield was called The Harris Stadium after its owner, five-time world champion, and the most successful British sprinter before Sir Chris Hoy, Reginald Hargreaves Harris.

Fallowfield Stadium was opened in 1892. It incorporated a red shale cycle track, an athletics track, and a football pitch. The 1893 FA Cup Final was played at Fallowfield, and it was home to both Manchester Athletics Club and Manchester Wheelers. The annual Wheelers track meeting was the high point of Manchester’s racing year.

We found out if an aero bike really is faster

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Catapulted

In 1921, 20,000 spectators packed in to watch a Wheelers meeting when Paul Guignard of France lost control of his bike in the motor-paced race. Motor-pacing was why Fallowfield’s bankings were so steep, but in 1921 the surface was still red shale. It was compacted using heavy rollers but could still break up, and was generally looser off the racing line.

Guignard’s pacer went slightly wide at one point, and his rider’s tyres bit into the loose surface, catapulting the Frenchman from his bike. Thankfully he survived.

By 1947 the Wheelers’ meet was attracting 5,000 fewer spectators, but they were treated to British riders Reg Harris and Tommy Goodwin overpowering stiff European opposition to win the two big events; the Vi-Tonic one-lap scratch and the Muratti Cup 10-mile.

>>> Icons of cycling: Leicester Velodrome

One of the most unusual races at a Wheelers meeting was the Sputnik team pursuit. The Sputnik was a Perspex fairing made locally that covered a standard track bike. A solo rider would use it to challenge teams in a pursuit race, and the super-aero Sputnik always won. It once did a flying mile time trial at nearly 38 miles per hour, a nifty team pursuit pace even today.

The Sputnik is on display inside Manchester Velodrome now, close to the bronze statue of Reg Harris. They are fitting links between the new velodrome and its spiritual father in Fallowfield. The last races were held there in 1976, and the stadium was demolished in 1993.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast

-

Madison Flux short sleeve jersey review: functional and affordable

Madison Flux short sleeve jersey review: functional and affordableThe road cycling jersey delivers top performance for a budget-conscious cyclist

By Hannah Bussey

-

I pitched a top-end all-road bike against a top-end gravel bike, here's what I found

I pitched a top-end all-road bike against a top-end gravel bike, here's what I foundMulti-surface machines go head-to-head-to-head and categories clash as Tim Russon rolls up for the ultimate do-it-all bike showdown

By Tim Russon