It’s never too late to make it to the top, meet the riders who did

To make it to the top, you need to start young, right? Think again! Chris Marshall-Bell meets riders who started later in life, yet rose to the highest level

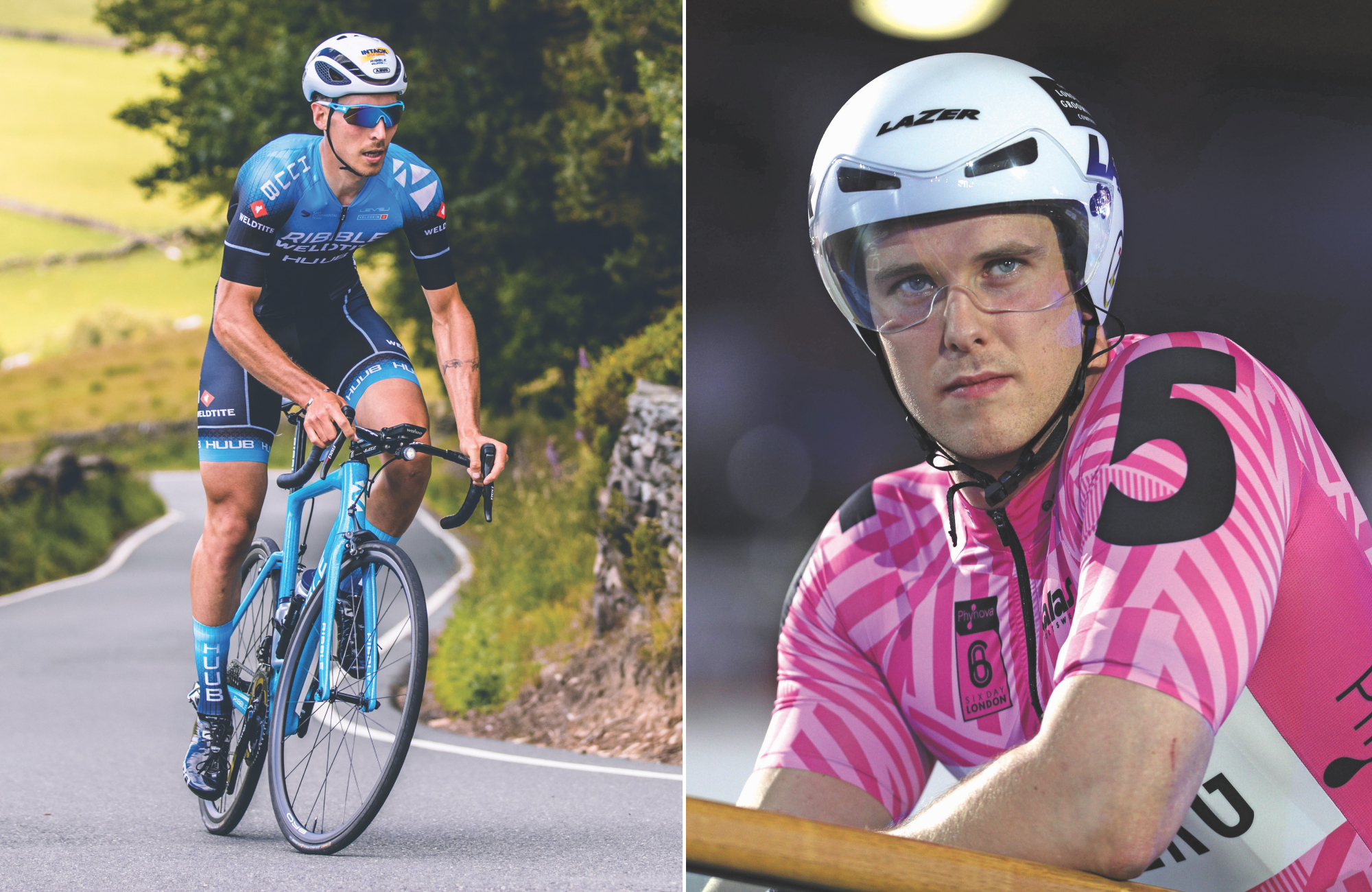

(Ribble/Getty)

We all know the pathway to turning pro: sportsmen and women start their sport young, commit wholly in their mid-teens, and by the time they are in their early-20s, all they’ve ever known as an adult is being a professional athlete. But that isn’t the only route by which those we admire, our cycling heroes, have become so masterful that they’re paid to do what is, at its core, their passion and hobby. Whether your goal is to become an elite category rider, to win a regional championship on the track, a World Masters Championship, or even land a professional contract and win UCI races, it is almost never too late.

"The performance trajectory of a cyclist is: improving up until about 30, then plateauing until about 40," Richard Davison, a professor of exercise physiology at the University of West Scotland, tells Cycling Weekly.

"There are certain elements at 40 you could not achieve in your teenage years, but between 20 and 40, the changes are relatively small. It is only from about 50 that there is a significant decline in actual performance."

Alex Spratt, a former rugby union player who had trials for England, started track racing aged 27 and holds a personal best for the 200m individual pursuit of 9.987 seconds – the first amateur to record a time below 10 seconds.

"Physiologically, I am still increasing my power and speed and will continue to do so until I am 35 or older," says the 30-year-old. More from Spratt later.

Changing the narrative

The narrative, despite a smattering of isolated cases to the contrary, is that if you’re not a professional by your early-20s, you never will be. Perhaps it’s time to overturn this idea. "Is there a major difference in physiological potential between a 15-year-old and 25-year-old? I would say no," Davison says. In other words, starting out in your mid-20s may not place you at a significant disadvantage. In fact, it may even confer certain advantages – what if late-starters hold the ace card?

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"We may not have been in an athletic institution, but we have more life experiences and can draw on that," says Australian pro Brodie Chapman, who started racing professionally in 2018, aged 26. "I don’t think, ‘Oh s**t, I’m at a disadvantage because they have 10 years more experience’. I was a backpacker in my early-20s and had to navigate different cities, languages, accommodations, foods, staying with people who I didn’t know."

Now 29, Chapman believes that her life experience gained before she got serious about cycling works to her advantage.

>>> Subscriptions deals for Cycling Weekly magazine

"I didn’t know anything about training, nutrition or physiology, but I have been to uni, and having a degree makes it easier for me to read and pick out information that will serve me as a cyclist."

The Women’s WorldTour rider also thinks her years make her more resilient and mentally stronger.

"When you’re young, it feels all very big, like time is spilling away from you and an injury would kill off all your chances. But I have been through setbacks in work and normal life. I have had these feelings before and I have the tools to deal with them. I know myself and my limits, and I can deal with loss and adversity."

Spratt talks about the mental benefit of low expectations while starting out in cycling. "I’d do a time and then ask if it was good or bad, because I didn’t know. Those who have been in the sport a while are fighting against others and their own times."

This bright-eyed freshness, thinks Spratt, made him less prone to disappointment.

"Younger people might be more advanced technically and tactically, but they can over-think things and let things get in their head too much. I have the maturity and age to cope with that. I want to better myself, not necessarily be better than everyone else. Generally, coming in later has been an advantage because of the hard shifts I have had in life and my sporting background."

Technique is key

Some late starters are very, very late – getting serious about cycling in their 30s, 40s, 50s or even after retiring from work. Veterans and masters competitions exist because there is a thirst for competition.

"We all at some point bump down the slope of age-related decline, but boy can we mould it and give ourselves the right stimulus to slow that decline, if not improve," adds sports scientist Davison. "There is no reason, physiologically, why you can cannot get back up in line with your optimal ageing profile. Your body will adapt to training. Don’t be shy of high intensity exercise."

One very late starter is the reigning World Masters points and individual pursuit champion Andrew Bruce. He made his racing debut eight years ago, aged 41. Key for him was mastering technique as quickly as possible.

"I got some old Tacx rollers and for three weeks they seemed ridiculous, dangerous and I couldn’t ride them,” recalls the Scotsman. “But I eventually focused on learning how to ride them. You have 36cm to ride within, so you can’t wobble, and you learn how to ride where you want to be riding. You can identify someone in the bunch who can ride on the rollers – because those who can’t, wobble everywhere."

Bruce’s headline successes have come on the track, and he believes even recreational riding on the boards can have a significant impact on a road racer.

"Riding the track teaches you the ability to control your speed, because in a bunch, your brakes are your left and right legs, and you have to control your rhythm on the track and adjust accordingly to what other riders are doing,” he says. “Compared to road riding, you’re much more aware of where your front wheel is in relation to the back end of other riders and how stable you are."

Out on the road, Bruce discovered the importance of effective cornering. "You have to corner confidently, adjust your position in the saddle to get your weight set up as you go into a corner. If you can’t corner in a crit race, you’re spat out of the back."

Beating the challenge

Let’s not be idealistic, there are major challenges for late starters: naivety, tactics, technique, time, family sacrifices and finances. And perhaps most importantly: age. The adage goes that children learn faster, and the science tends to agree. The prefrontal cortex of the brain, where working memory is stored, is less developed in children, allowing them to be more creative and flexible – essentially, they have more space to learn. Adults’ prefrontal cortex is more developed, less well suited to invention, but that’s not to say we can’t learn – provided we have the desire.

Gripped by the simple pleasure of being on a bike, and driven by improvement that eventually led to winning, Damien Clayton committed completely to the sport after a charity bike ride from London to Brighton in 2016, aged 23.

"In my first year, I rode 1,200 hours while having a full-time job," says the 27-year-old, who won the 2019 GP des Marbriers in France – his maiden UCI race – and now rides for Ribble-Weldtite. "That volume was crucial, as it fast-tracked my development. People asked why I was doing so much, but it was because I was bloody enjoying it."

Being able to accumulate fitness and build resistance will lead to what is commonly referred to as a ‘cycling engine’ – cardiovascular fitness – and many late starters report success in local races simply by possessing greater raw strength than their peers. According to the research, it takes around four months to develop our ‘cycling engine’ and maximise VO2 max, from then on, it’s a case of maintaining volume and intensity – economy, resilience and endurance continue to improve over many years. Of course, once you’ve progressed through the categories and are facing tougher competition, the barriers are no longer solely fitness-related.

"There is a huge amount of skill and technique required to race effectively and avoid wasting energy," Davison says. "This is harder to pick up, but is all very coachable. I tell coaches that you will progress a greater amount in a short time by improving technique rather than physiology."

OK, but what exactly is cycling technique? It’s a question that another late starter, former 800m international runner Dani Christmas, found herself asking after she switched to cycling in 2013 aged 25.

"When you’re watching cycling on TV, you think it looks so easy. ‘They’re riding in a straight line, how hard can it be?’ But do it yourself and the first time you think ‘holy moly, this is terrifying’."

Daunted by bunch riding for two years, Christmas – who now rides for Lotto-Soudal – already knew she had potential.

"I had a good engine, so I won local races without riding in the middle and just sitting at the back or at the front with a quick smash up the outside. When I actually had to force myself to ride properly within the bunch, it hit me just how much skill was required. You have to learn how to control your bike as best as you can, and working on my bike-handling skills progressed me more

than anything."

The consequences of lacking bunch skills barely need spelling out. "If you’re new to racing and suddenly someone leads on your shoulder, the chances are you will freak out, slam on your brakes and the person behind you won’t have time to react," says Christmas. "You have to learn to read people’s body language so that you can analyse what they will do, giving you that extra reaction time if they deviate from their line or they signal to you that they’re going to move."

Aware of the critical omission in her repertoire, Christmas began working on her skills, even in 2018 after she started racing for Bizkaia Durango-Euskadi Murias, her first UCI team, aged 30.

"Pick a white line on the side of the road and practise riding as slow as possible. The slower you go, the harder it is to stay on the white line," she advises. "When riding in a bunch with 38cm handlebars, you have a gap either side of you of around 6cm to the next rider, so you have to be able to keep your bike still and not move around all over the place. Only when I set aside time every week – even just 20 minutes – to work on these skills did I make a big step forward."

The 32-year-old explains how she also had to work hard on her cornering.

"On my rides, I planned routes where I used corners that I could safely take four or five times on a ride, and I worked on that until I was confident," she says. The pro road racer has since taught skill-based workshops for beginners in traffic-free, safe, closed circuit environments, something she regrets not doing during her formative years.

"You will learn more in one afternoon than I did in three seasons of racing."

To learn tactical astuteness, it is necessary to race again and again. Chapman, who now rides for FDJ-Nouvelle Aquitaine Futuroscope, and has eight UCI wins to her palmarès, has experienced this first-hand.

"Stepping up to the biggest races, I had to learn how to distribute energy more wisely. It’s not a 100m sprint race, it’s about who can apply energy in the right moments and throughout the race. You can’t do that instantly, you have to learn how to hold a good position and that’s the most energy-sapping thing to do. There is no way to be good at that instantly. You do that by racing."

>>> Cycling Weekly is available on your Smart phone, tablet and desktop

In learning from your races, your friends and coaches can help you. "You can’t watch yourself, so if you can get someone to watch you and maybe even film parts of the race, especially if it’s on a closed circuit," Christmas suggests. "That way, you can receive feedback and you can analyse the race: what position was the winner in? When did I burn my matches? Write three things down to improve, and if you keep making the same mistakes, you then set process goals to improve on."

Expert view

Having an expert to cast their judgement made a big difference to Clayton. "One hundred per cent, having a coach has been integral to my results," the Yorkshireman says. Having trained without a coach for the first two years, he was approached by Canyon dhb Soreen rider Rory Townsend after the South East Regional Championships in 2017 – a race where he finished third, joining winner Townsend and fellow late-starter Alex Richardson on the podium.

"The first thing Rory did was laugh at what I was doing," Clayton says. "Once you click with a coach, it’s the most important thing and, in my mind, the best investment you can make into your results. I don’t think I would have achieved any of this without him as a coach. He’s an advisor, a good friend... and you can’t put a price on what he has been able to do for me within the sport."

Spratt hired a coach almost as soon as he started cycling. "I didn’t have a clue how to train in the sport," he admits. "In rugby, I trained until the day before a match, played and then had a day off. I had no idea about peaking."

The impact of having guidance was observable within his first year. "In the 2018 National Championships, I finished fourth in the individual pursuit and I had no idea what I was doing. A few months later, I became the first amateur to ride sub-10 seconds and that was only because I had a coach who understood the sport and knew what I needed to do and why I needed to do it. Without that help I wouldn’t have got to where I did... Without a coach you’re going in blind."

Focus on the positives

Not everyone has to dream big, but they can achieve their potential. There will be doubts along the way, though. "Be kind to yourself," Chapman advises. "Instead of being caught up in how challenging it is or how much you have to learn, congratulate yourself on each achievement. Finishing a race is an achievement."

All of the late starters CW speaks to have hardships to share, common problems they each overcame, and they are all unanimous in their conviction that age need not be a barrier to achieving at a very high level. Chapman urges older riders not to get hung up on a sense of being disadvantaged: "You may ask: should I be here? And after some success: how did I get here? But everyone has a story of why they are not as good as they could be, or why they are less experienced, and I saw a lot of other women who had entered the sport late. I soon realised my story is not unique." Let’s not forget, racing is the great leveller. "Once you’re on the start line, everyone is equally your rival; age no longer matters."

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Cycling Weekly, on sale in newsagents and supermarkets, priced £3.25.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

A freelance sports journalist and podcaster, you'll mostly find Chris's byline attached to news scoops, profile interviews and long reads across a variety of different publications. He has been writing regularly for Cycling Weekly since 2013. In 2024 he released a seven-part podcast documentary, Ghost in the Machine, about motor doping in cycling.

Previously a ski, hiking and cycling guide in the Canadian Rockies and Spanish Pyrenees, he almost certainly holds the record for the most number of interviews conducted from snowy mountains. He lives in Valencia, Spain.

-

How I got my non-cyclist friend hooked on riding bikes — and how you can, too

How I got my non-cyclist friend hooked on riding bikes — and how you can, tooWith a little bit of gentle guidance, “bikes aren’t my thing” can turn into “when’s our next ride?”

By Marley Blonsky

-

Madison Flux short sleeve jersey review: functional and affordable

Madison Flux short sleeve jersey review: functional and affordableThe road cycling jersey delivers top performance for a budget-conscious cyclist

By Hannah Bussey