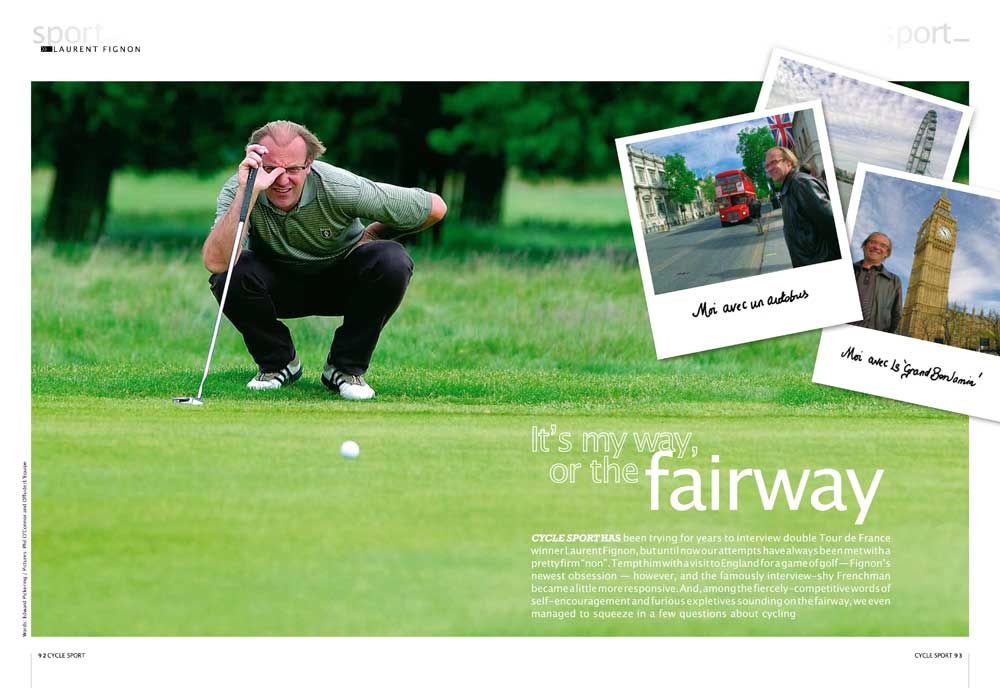

Laurent Fignon: My way or the fairway

In 2005, our sister magazine Cycle Sport persuaded Laurent Fignon to be interviewed by bribing him with a game of golf. The Tour winner was notorious for not wanting to talk about his riding career, but his love of golf was enough to tempt him to open up to Edward Pickering.

There is a famous photograph of Laurent Fignon, rounding a corner in the fateful final time trial of the 1989 Tour de France. He is wearing the yellow jersey for the 22nd and last time in his life, and his face is drawn and lined.

From that photo alone, it is possible to guess that he is undergoing one of the most dramatic and painful reversals of fortune in cycling history.

Fignon's glasses are balanced on his nose, his leg muscles flex with immense power, and his body leans over as his bike swoops round the corner. You can sense the speed he is riding at, and imagine that his bike is flying over the cobbles of the Champs-Elysées. But it is not enough, and behind the focused determination there is an expression of desolation.

This is the Laurent Fignon that everybody remembers. The Laurent Fignon who lost the Tour de France by eight seconds to Greg LeMond on the final day of the race. The Laurent Fignon who wept bitter tears of defeat on the Champs-Elysées and vowed never to ride his bike again.

But remembering Fignon like this is to forget that this was a man who won two Tours de France, a Tour of Italy and several Classics. And, for long periods during the 1980s, was the best cyclist in the world.

"I am a winner, I like competition, and I like winning," Fignon explains to Cycle Sport. "Competition brings out the best in me. When I was a rider, I could never go well in training, but in competition it was different," he continues.

Breaking his silence

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Laurent Fignon has agreed to give Cycle Sport his first big interview for many years, tempted by the proposition of a day spent indulging his new passion - golf - in exchange for a chat about his career on the bike [see separate story].

"Normally I always say no to interview requests. I don't find it interesting to talk about the past," he says. But Fignon's was one of the most enigmatic and interesting cycling careers in the history of the sport. And Fignon himself is gifted with an analytical brain, and an outspoken nature. His is a story which deserves retelling.

Fignon has always been his own man, and true to form, is an hour late for our meeting, having made a panicked call from a Paris traffic jam at around the same time as the train he was supposed to be on was pulling out of the Gare du Nord. He is stocky, with a good tan, and he is smartly dressed in a purple jacket and shirt.

The trademark hair is still long, blond and wispy. It floats around his head, and seems to follow him independently, rather than being attached. His glasses are an updated version of the ones he wore throughout his cycling career - modest and fashionable, but unusual simply for the fact of their being there. Cycling is not a sport which is kind to the short-sighted, and Fignon's spectacles marked him out as an oddity within the peloton. He has lost the goatee beard which grew along with his media career as a commentator for Eurosport. This year he stopped working in television, and the trendy facial hair has gone, too, making him look younger than his 44 years.

Fignon has saved us a surprise. His reputation as a cyclist, and even beyond his cycling career, is that of a tetchy, impatient, stressed individual, prickly and defensive. An interviewer's nightmare. But he greets us with a smile, gently mocks us about the standard of food in England, and talks expansively of the terrible traffic problems in his home city.

When he talks, Fignon is engaging, but he is also the kind of person who is happy to sit and stare into space. Some people can't stand silence when they are with other people, but Fignon is comfortable to sit without speaking if he feels there is nothing to say. He is obviously shy, but bridges the gap to other people with a slightly nervous laugh, which seems to relax him, and often grows into a wide smile.

"I'm a solitary kind of person. I'm not talkative. In a group I talk, but I can also be quiet. With friends it's different, but it's probably true to say that I listen more than I talk," he tells Cycle Sport.

Fignon occupies an ambiguous place in the pantheon of French sporting heroes. It is well known that the French public love a gallant loser - the most popular cyclist in France is Raymond Poulidor, whose inability to win the Tour de France throughout the 1960s and 1970s earned him the affectionate moniker of the ‘Eternal Second' and ensured that he never had to pay for another drink. Fignon has lost like no other rider in Tour de France history - an eight-second gap separated him from 1989 winner Greg LeMond. But the French public always mistrusted the dominant style with which Fignon crushed his rivals in the 1984 Tour.

Losing in style

There is a story related by novelist Julian Barnes which sums up the French attitude to sport - better to lose with panache than win ugly. He overheard a waiter in a restaurant soon after France were eliminated from the 1994 World Cup qualifying rounds by Bulgaria. "It was a pretty goal," sighed the waiter of Bulgaria's last-minute winner.

Fignon disagrees with this philosophy, but is also willing to admit that 1989 was not, in the long run, a bad thing for him.

"It's not like that with me. Winning comes first!" he insists. "Losing is not good. Look, what does history remember? The winner before everything. History remembers the winner, and forgets the circumstances," he continues.

Here lies the biggest contradiction in Fignon's life and career. He was a protagonist in the most exciting race in Tour history, and he is remembered for coming second.

"Yes, I am remembered because I lost a race. But when I lost I was not happy. It was a great disappointment, very sad for me. If I had won that day, I would have been a three-time winner. And it's indicative of the French attitude to sport that I am remembered more as the guy who lost the Tour de France by eight seconds," he says.

"But I'm lucky to have earned myself a certain notoriety in France, mainly thanks to 1989. Today, and it is with great regret that I say this, in France it can be better to have lost than to have won," he admits.

"It hasn't been a bad thing for me these days. Me, sure, I would have preferred to have won, but losing that race has been profitable for me."

According to an interview which appeared in French newspaper L'Equipe, Fignon stayed in his apartment, crying, for days after his defeat by LeMond. Now, Fignon has managed to dissociate himself from the events and is able to look at it more dispassionately, even if he cannot help feeling annoyed about the way victory was taken from him.

"The main problem during the 1989 Tour was that the handlebars LeMond used were not authorised. And without them he wouldn't have won," Fignon says. "And I had a little problem the last day [a saddle sore], which handicapped me a little. When I look back over the whole race there were some little tactical errors that I made. But LeMond could say all of those things, too. The result is the result.

"People remember the Tour of 1989 because it was a nice fight, a good scrap. It was an interesting Tour, as Tours go. I was disappointed at the time, sure, but over time the disappointment has disappeared. There are more serious things in the world," he says.

Two sides to his story

The two common images of Fignon, then, are the heroic loser of 1989, and the distant, arrogant champion of 1984. For a shy individual, it is sometimes easier to hide behind a stereotype than show one's true self. Fignon made few efforts to contradict the media's representation of him as aloof, prickly and touchy. Cycle Sport expected a difficult interview because of this reputation, but Fignon's charm and openness surprised us. We tell him he is more relaxed than we expected.

"Relaxed? I've no reason not to be," he says. "With the press I was always honest, spoke the truth, and said what I think. But some of them made changes and interpretations of my words. After that I said, enough, no more Mr Nice Guy.

"Put simply, professional cycling is one of the only sports where competitors are so close to the public. The public are close enough to touch, and they do. People imagine they can, and they don't understand that riders need concentration before a stage. I would be thinking of the race, and then somebody comes and talks to me. It's true that it totally pissed me off. Before the prologue of the 1989 Tour there was a scrum of photographers fighting over a picture of me, and there's me trying to concentrate. There must be a minimum of respect, no?" he says.

Many ex-professionals, including Tour winners, live their lives looking back to the times they were achieving their great victories. Around any race in France, you can see ex-professionals from the 1950s onwards hanging around the hospitality tents, being presented to the crowds, reliving past glories with their fellows and, most of all, perpetuating their links with the cycling world. At the annual Retrouvailles race, which ran for the last time in 2004, old pros in their hundreds get together for an exhibition race and banquet, and the stories and laughter go on late into the night. But Fignon has deliberately separated himself from this kind of scene.

"I don't understand people who are nostalgic. I don't get nostalgia," he says. "I pushed myself to extremes. I did the maximum that I was capable of doing, and I will never again be able to do it. Riding a bike will never be as easy as it was during my best years. Riding up hills is extremely hard and it doesn't interest me to train any more. I'm an optimistic guy, and I look forwards, not back. In my house, I never speak of cycling. Never. It's a part of my life which is finished, and I'm happy about that. That's not to say that I regret nothing. On the contrary, I am aware that I have lived through some extraordinary moments. It was fantastic and I loved it. But no nostalgia.

"But in life I'm not happy. In fact, I am never happy. I am eternally unsatisfied with things, and I try always to find new things to do," he continues. "For example, when I won my first Milan-San Remo in 1988, I won it in a sprint ahead of Maurizio Fondriest. Great. But I said to myself, it would have been better if I had been on my own," he jokes.

Countryside allegiance

Fignon discovered cycling as a teenager, when he was growing up in the countryside near Paris. He has always been depicted in the cycling press as an urbanite, a sophisticated Parisian, but he sees himself as more of a country boy.

"I was born in Paris, but grew up in the country-side. Until I was 23 I lived in the countryside, then I moved back to Paris," he says. "I did lots of sports as a kid. I played football, athletics, a bit of rugby, volleyball. It was only luck that put me in cycling. It's an outdoor sport, so I did a lot of it. I always hated being indoors," he explains.

"I was always very precocious. I started riding the bike as a juvenile, and I was good right away. I didn't race my first year, just riding with my friends, but I was better than them. And then the first race I did I won. I didn't win a huge amount after that, just four races, and the next year, only one. But the year after I won all the time, 18 races out of 36. Every time I wanted to win I did," he continues.

Fignon was blessed with all the attributes necessary to become a professional cyclist. "I don't know why I was good, it was just a gift," he says. "At 18, I didn't train much. I rode twice a week, not more. And I was lucky to find a good trainer when I was young, who taught me to ride for pleasure. That was important for me, and I rode my whole career for pleasure, and for winning. Not for money. I stopped when I was no longer getting any pleasure out of it," he continues.

Fignon was hired by Cyrille Guimard and Bernard Hinault's Renault team in 1982, at the age of 21. The young Fignon had no idea that, within a year and a half of turning professional, he would have won a Tour de France, and come close in the Vuelta a Espana, as well as miss out on a certain win in a Classic. He rode the 1982 Giro d'Italia in support of team leader Hinault, but took the pink jersey after Renault won the team time trial and Fignon broke away on the second stage with Australian Michael Wilson. He lost the maglia rosa the next day in the time trial, but after four months as a pro he had already had the experience of leading a Grand Tour, and setting off last in a time trial. Fignon became Hinault's most trusted mountain domestique.

"I was already the only rider who could stay with him in the mountains," Fignon says of his leader and future rival. "I stay in seventh place for two weeks, riding with Hinault on all the climbs, I'm dropped near the top, back on during the descent, then ride in the valleys for him. One day, I do all that, then I lose 15 minutes in a 15-kilometre climb. Dead."

Fignon tells cycling stories in the present tense. For an individual who denies nostalgia, who professes only to look forward, this is initially confusing. If the past is so distant, giving it immediacy by telling stories about it as if they are happening right now seems contradictory. But perhaps it is a sign that he is comfortable with that period of his life being over.

"The following year, I ride the Vuelta, seventh overall and I win a stage. But I never attack, staying with Hinault on every stage. He wins, but it was me who gets rid of everyone for him. And that takes me to the Tour in 1983," he says.

A glorious era

In the same way that historians say that the swinging Sixties started in 1967, the cycling Eighties started not in 1980, but with Fignon's victory in the 1983 Tour. With defending champion Hinault injured following his gruelling Tour of Spain victory, the race became a joyful and unpredictable free-for-all.

Peugeot rider Pascal Simon seemed to have the race sewn up, but his collarbone was cracked in a crash, and he was forced to retire after several days of riding in considerable pain. Riding into the yellow jersey vacated by Simon was Tour debutant Fignon, who had already put in some stunning efforts

in the Pyrenees. A back-breaking ascent of the Tourmalet in the wake of stage winner Robert Millar, and subsequent grinds up the Aspin and Peyresourde, had put him in second place overall on a day when the favourites attacked right from the start.

He defended his jersey on Alpe d'Huez, and finished close to the favourites on the tough stage to Morzine. Fignon's victory in the final time trial proved that he deserved the yellow jersey. His win was the first by a young pretender since Hinault himself won for the first time in 1978.

"I was lucky to win in 1983, but you need luck to win. Nobody wins without it," he says. "Take this example. In 1982, my first year as a professional, Blois-Chaville [now Paris-Tours], the last Classic of my year. The roads were my training roads, I knew the parcours like the back of my hand. I trained specifically for it behind the Derny, and I was in great form," he recalls, and switches to the present tense.

"There's one part, I know it by heart. There's a climb, flat at the top, and the wind always blows. At the top, it kicks off, there is a crash, Jan Raas goes down. Echelons form, and I am the very last person to get on the back of the first echelon. Nobody sees us again. I attack 30 kilometres from the finish.

"My lead is 45 seconds, 30 seconds, 40 seconds. Then my crank breaks. No luck. That's what decided the race. I was going to win it, then I had bad luck. And then luck was with me in 1983. That's racing, and that's life. If Hinault had been fit in the 1983 Tour, he would have won, because he's the team leader and I am the domestique. This is what life does," he says.

"But nobody can say I did not deserve it. At times you have a bit of luck, at other times you have none. And you don't know when they are going to happen."

No plain sailing

The 1983 Tour wasn't plain sailing for Fignon. He has memories of extremely tough periods, even early in the race.

"We rode to Roubaix over the pavé, and I didn't know how to ride on cobbles. It was so hot that I burned my hands on the handlebars. I hold them too tight, give myself blisters, and at the finish I pour Perrier all over myself to cool down. The next day we had 300 kilometres to Le Havre, and what did we have for the last few hundred metres? More pavé. Then for the time trial at Nantes there is conjunctivitis going around the bunch. I do the whole time trial with one eye closed," he says.

Fignon traded his luck in 1983 for unassailable strength in 1984. He was a year older, and as he lined up for the 1984 Tour he knew he had been the strongest rider in the Giro [see separate story], and had extraordinarily good sensations in his legs.

"When I won the Tour in 1984, it was easy. Every day easy. No problem. My legs didn't hurt, great form, great legs. Fantastic!" says Fignon.

Fignon's old team leader Hinault, who had jumped ship to the new La Vie Claire team, was back for revenge in 1984, but Fignon, having ridden for a year in Hinault's shadow, would not sacrifice his place at the head of the race.

"It was a real scrap I had with Hinault. He never admitted defeat, attacked non-stop in the mountains, every day from the first to the last. Even on the flat stages, he was going for all the bonus sprints, him and me. And if I was badly placed at these points, he'd carry on with the attack and we'd have to chase for 30 kilometres to get him back."

"But I won by 10 minutes. I was stronger than him, but he was still good enough to come second." If one moment summed up the hierarchy of the 1984 Tour, it was the moment when Hinault, desperation forcing him to take extreme tactical risks, attacked on the road to Alpe d'Huez. The press reported that Fignon laughed out loud at Hinault's efforts, stoking up a rivalry between the two riders, but Fignon insists there never was any bad blood between him and Hinault.

"No, I didn't laugh. It was very hard, we're on the Laffrey, a very, very steep climb. He attacks, I bring him back. He attacks, I bring him back. He attacks again, I bring him back. It pisses me off, so I attack, and leave everybody except Herrera. We ride and we ride, and Hinault comes back onto us in a little group, and then attacks right away, four kilometres from the base of Alpe d'Huez," he says.

Best of rivals, best of friends

"It made me smile, because it was a tactical error. It wasn't a lack of respect, and it was the press who were trying to build up a rivalry anyway. We like each other a lot. Well, when we were fighting for the Tour we weren't the best of friends, but there's no problem now. We were rivals. We are friends. But it's normal in life. You like some people, not others," he continues.

Although Fignon dominated the Tour de France in 1984, injury in 1985 led to several fallow years before his famous comeback in 1989. But it is important to remember that throughout this period he was competitive in Classics, and other Grand Tours, even winning a Tour de France stage in 1987 at La Plagne. Fignon and Hinault were the last Tour winners to show a real interest in riding well throughout the year, and when Fignon was on form, he could legitimately claim to be the best rider in the world, especially in 1989. That year, although his slim defeat in the Tour de France casts a long shadow over his other results, he won Milan-San Remo, the Tour of Italy, the Tour of Holland and the Grand Prix des Nations.

"In 1984, during the Tour de France, I wasn't far from perfection. Likewise, in 1989 I had some extraordinary moments. When I won Milan-San Remo there wasn't a single moment when I felt pain in my legs, and there was not a single rider who was capable of staying with me.

"Sometimes I spoke with my team-mates, who told me their legs hurt all the time. During races, during training. I didn't understand it - they had never gone a day when their legs did not hurt. I can say that during the 1984 Tour de France my legs pretty much did not hurt the whole way round," he explains.

It is difficult to believe that any cyclist can ride the rest of the world's best into the ground over three weeks in the French midsummer without suffering the occasional twinge, but Fignon believes this is what set him apart from his rivals.

"I'm not saying that cycling was easy, of course. It was very difficult. But this was one of my advantages, I could support pain and suffering for long periods of time. For many hours. In fact I went through calvary on many occasions, but I never gave up," he says.

"In fact, at the start of 1985, I was much stronger than the year before. If I hadn't had the injury which stopped me then, I can promise you that my career would have been a different story. I was incredibly strong, and it was easy. Then it stopped, just like that."

Raising the game

After 1989, Fignon struggled to recapture his past form. By 1991, his best efforts were only good enough for sixth overall, ahead of his old nemesis Greg LeMond, but far behind the new generation of Tour specialists led by Miguel Indurain. He left France for the Italian Gatorade team, riding as a domestique de luxe for Gianni Bugno, and soloed to a spectacular last Tour stage win in the 1992 Tour. He finally called time on his career in 1993, and for the first time there is a hint of bitterness at his exit from the sport.

"I wasn't sad to retire, and it seemed natural at the time, but looking back, maybe it wasn't so natural after all," he says. "The 1993 Tour was my 12th year as a professional. I was very experienced. By that point I could tell if I was in good form, or if I was in bad form. I knew my body by heart, all the signals.

"In 1993, I knew that I was in great form. There was a mountain stage to Val d'Isère, over the Télégraphe and Galibier. I felt fantastic, and attacked at the foot of the Galibier. I felt I was climbing well.

"But in the blink of an eye, 30 riders had come past me, and I believed I was in good form, 30 riders, just like that. And after that I was riding with people I did not believe I would ever be riding with in the mountains. People who were riding on EPO," he says.

"At that very moment, I knew that I was dead. Too old. Finished. I rode in, tried to lose as little time as possible, and abandoned the race the next day. Me, a rider who never abandoned."

Fignon has made a number of cryptic remarks over the course of his life on the subject of drugs. While he deplores the rise of EPO in the peloton, he admits that twice he tested positive, but insists that on each occasion he was the victim of mysterious forces in the testing community.

"It was a sombre story from Belgium. I don't know what happened, but it really annoyed me. The flasks disappeared for three days, and then the result came back positive," he says.

But he has often refused to deny outright drug usage. In 2003 he said to L'Equipe: "People can say what they want. Perhaps I was doped but that is only my concern. The whole world thinks that we are all doped our whole lives, which is totally false."

Fignon explains: "The problem with doping is that 50 per cent of dopers do it out of choice, the other 50 per cent do it because of the others. People prefer to win lots of money than to live a long time, and doping will continue because there are always people who want to finish first at all costs. But the first aim of the rules should be to accept and tolerate certain things, but as soon as the limits are breached - out."

Fignon has no regrets about his life and career. These days he stands with one foot in the cycling world and one out of it, and lives the life of a contented ex-professional, working at reducing his golf handicap, running the annual Paris-Corrèze bike race and selling 50,000 low-end bikes in supermarkets every year. "I made some mistakes. But I'm very happy with my career," he says.

"When I started my career, I never imagined I would achieve what I did. Even when I turned pro I didn't think I could do the things I did; even lose the Tour de France by eight seconds. "I was simply happy on my bike. It was my thing and I liked it."

This article first appeared in Cycle Sport August, 2005

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.

-

FDJ-Suez, SD Worx-Protime, Lidl-Trek confirmed for Tour of Britain Women as strong list of teams announced

FDJ-Suez, SD Worx-Protime, Lidl-Trek confirmed for Tour of Britain Women as strong list of teams announced18 teams set to take part in four-day WorldTour stage race

By Tom Thewlis

-

Cyclists could face life sentences for killing pedestrians if new law passed in England and Wales

Cyclists could face life sentences for killing pedestrians if new law passed in England and WalesReckless cycling currently carries a maximum two-year jail term

By Tom Thewlis