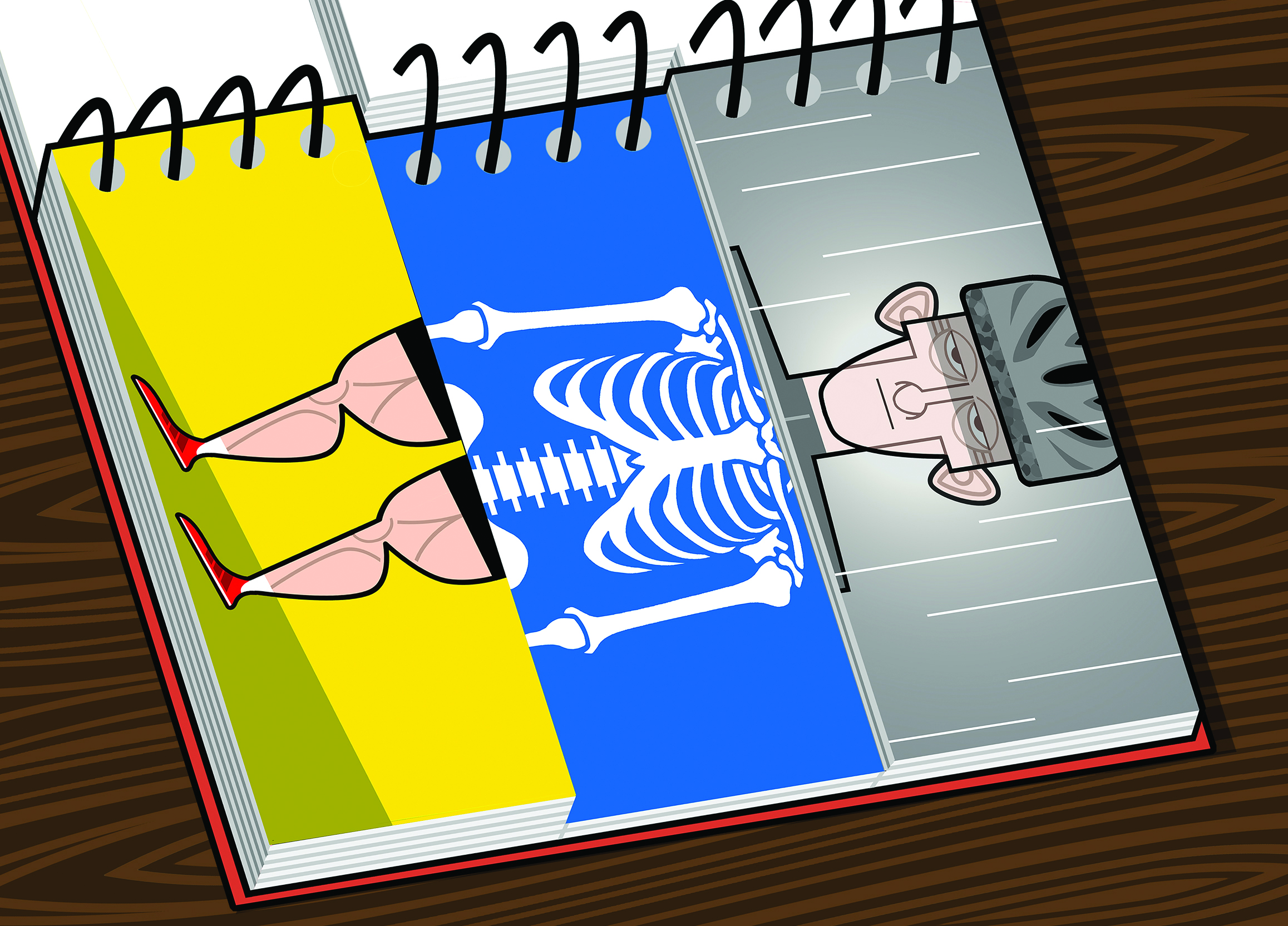

Macho or masochistic? At what point does proving your toughness get too much?

Sports psychologist Dr Josephine Perry takes aim at cycling's macho myths

(Getty)

Rapha recently produced a drinks bottle printed with the slogan “a slice of watermelon” on one side, and on the other: “To achieve race weight, Marco Pantani would, according to legend, ride for six hours on nothing more than water, returning home to just a slice of watermelon.”

Just water indeed – in hot water was where Rapha ended up. Anyone who has read biographies of Pantini knows it wasn’t fruit that fuelled his performances, but illegal performance-enhancing drugs. Even so, the myths of the heroic, self-denying cycling purist perpetuate – and are potentially extremely harmful. They encourage us to idolise an unattainable ideal of macho hardness, and to respond to every difficulty with ‘man-up’ or the crasser shorthand HTFU, cherishing terms like “suffering” and “pain cave”.

While the psychological term ‘mental toughness’ encompasses determination, focus and confidence, a common misinterpretation is that it’s all about tolerating ever greater amounts of pain. This is not good for wellbeing or performance; it’s counterproductive if not downright dangerous.

Forward-thinking coaches are moving away from the mental toughness approach and embracing mental flexibility. This means, instead of ram-raiding our way through stressful situations or setbacks, we adapt to them. We shake off rigidity and become agile, picking the relevant mindset and shifting perspectives as and when necessary, improving not only our performance but also our day-to-day lives.

In this feature, I want to interrogate and correct some of the insidious myths that arise from the macho ‘mentally tough’ mindset.

>>> Subscriptions deals for Cycling Weekly magazine

Rather than striving to train in a pain-seeking, masochistic way, treating our bodies as though machines, we need to become smarter, incorporate mental agility and harmonise mind and body. It’s time to demolish some macho myths...

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Macho myth 1: ‘Lighter is faster’

Cycling has a culture of applauding the slightness of riders. This love of lightness is pervasive. Recently, 20-year-old Deceuninck–Quick Step rider Remco Evenepoel said that while recovering from the injuries he sustained at Il Lombardia, he was so concerned about gaining weight, that he purposely lost 5kg. The year before, it was reported that his team boss Patrick Lefevere described him as “too fat”. Evenepoel admits his upper body is now just skin and bone. His extreme weight loss efforts are not unusual. Riders Jani Brajkovič and Rohan Dennis have talked about their disordered eating, and Chris Froome has discussed how riders often feel starving.

This under-fuelling and over-training doesn’t make great riders, just riders who are fragile and far more likely to break. When you don’t take in enough fuel, you don’t feed your brain the glucose it needs to make good decisions. When you starve your body, it stops making the hormones you need to function well. As a result, female riders lose their period and both genders risk bone fractures. This doesn’t bode well for a long sporting career.

Macho myth 2: ‘Bully your legs’

Jens Voigt had a mantra that most riders remember: “Shut up, legs!” It suggests a rider should simply put their head down and suck up the pain. Athletes are good at tolerating pain – a German study compared pain tolerance levels by asking people to hold their hands in ice water for as long as they could. Regular people managed on average 96 seconds. Ultra-distance athletes made it past the three-minute cut-off point and even then still only classed the pain as six out of 10.

Suck up too much pain and we’ll be onto the physio’s bench. The trick is to distinguish pain from discomfort. Pain is useful information, telling us we are overloading and need to change position or rest. Once we know the difference, discomfort can be tolerated.

Macho myth 3: ‘Pain is temporary – quitting lasts forever’

Another cheesy mantra – this one a favourite of Lance Armstrong – is that pain is temporary, whereas quitting lasts forever. There are two problems with this. Firstly, sometimes pain isn’t temporary – sometimes it is a long-term, chronic issue which will only get worse if ignored.

Secondly, it is rarely helpful to focus on the negative, unhelpful repercussions of an action. Sometimes, quitting so as to come back strong another day can be the wisest possible decision. Far more valuable to our performance is remembering why you want to do well, focusing on the positives.

Dr Noel Brick is lecturer in sport and exercise psychology at Ulster University, in Northern Ireland, and studies the internal chatter that reverberates through our head when we compete in sport.

“Research shows, during challenging moments like riding a solo time trial or pushing hard up a steep hill, what we say to ourselves – our self-talk – matters.”

Brick reminds us that pressure, fear, or guilt in our self-talk might work in the short term, but focusing on what we value is what helps us long-term. Two of his favourite mantras when he is training hard are: ‘I love this’ or ‘How lucky am I?’.

“These statements help to remind me of how much I enjoy the challenge of pushing myself, and how much I value being fit and healthy enough to do it.”

Macho myth 4: ‘Sleep when you’re dead!’

Riders trying to fit in work, family and training often find there aren’t enough hours in the day – and sleep is the first victim. This is lethal. Gareth Mason – a CW Fitness Project participant in 2019 – is convinced that his massive rise in FTP (from 350 to 395) in 2020 was down to the fact he worked from home during the pandemic, didn’t have to commute and thus slept for around two hours longer.

Coach and elite rider Jacob Tipper agrees that sleep is incredibly important. “Recovery is the biggest factor in improving, and sleep is the number one recovery method. It is legal doping. It is when our hormones are released and the adaptations come.”

Tipper appreciates that squeezing in plentiful shut-eye can be a challenge.

“A professional athlete has the time to sleep for nine or 10 hours a night, plus naps. For amateurs I coach, though, at some point there is not much more training I can set for them because, without extra sleep, they become unable to recover from it.”

It isn’t just our performance that suffers when we don’t get enough sleep – it is our health. One of the ways we can test the impact of losing sleep, is to study what happens to our health the day after the clocks go forward. A Finnish study found that the number of strokes rises by eight per cent, and the University of Arizona found the risk of heart attack rose by 24 per cent. So the macho ‘I’m too busy to sleep attitude’, doesn’t just harm our performance, it risks our lives.

Macho myth 5: ‘Go hard or go home’

The first thought many riders have after a poor performance is that they have been lazy and need to do more. Coach Tipper says often the opposite is true and that many riders in this position have been working too hard.

“I set training to create molecular adaptations. There is a real benefit in Zone 2, base riding.” To ride at an easy pace, riders need to use their minds, not their egos – and save their competitiveness. Aim to hit the targets of the session, not to surpass them.

Madeline Verdegaal, 24, is a rider with Team OnForm, and in the last year changed her approach.

“I’ve always been encouraged to incorporate easier, Zone 2 recovery rides, but I used to end up riding hard or not enjoying the rides because I felt as if I was wasting training time.”

>>> Cycling Weekly is available on your Smart phone, tablet and desktop

Recognising the problem, Verdegaal made a conscious effort. “I made it part of my winter goals to give easier rides a proper go without being tempted to ride harder, and I saw progress even without incorporating harder efforts.”

As a result, the Poole Wheelers racer’s base endurance has improved so she can cope better with the higher intensity in races, while her long ride endurance has also improved.

“I realised short high-intensity efforts will get you stronger, but without that base fitness there’s only so far they can take you. Once I realised this, there was more motivation to ride easier during those designated rides, because I knew I wouldn’t be impacting upon the benefit I could gain from the harder rides.”

Macho Myth 6: ‘The best cyclists go it alone’

Cycling can be a solitary sport – out on the road for hours at a time, but what makes us perform well is listening to others. You might well have a body shaped for riding, biomechanics that mean you pedal in efficient circles, and a VO2 max that would make a Norwegian skier envious, but you still need advice, accountability and inspiration. Often, that comes through getting a good coach.

After three years of self-coaching in time trials and reaching a plateau, Rob Bullyment, 47, began working with Tim Ramsden of Black Cat Coaching. It has made his training far more specific. He says: “It was the structure provided by Tim that brought me on. I think I had just never worked hard enough, in a controlled way.”

Working with a coach bought his 100-mile PB down by 20 minutes. It also helped knowing someone was rooting for him.

Macho Myth 7 : ‘A coach’s job is to make you push harder’

A coach should not be concerned solely with your performance. Your success depends on more than your physical condition and split times. Good coaches realise well-being comes first and that only happy athletes reach their full potential. The chauvinistic abuse that has been reported in high-profile scandals in recent years has no place in the sport. It’s high time cycling moved on.

Of course, the rider has a role to play too. If you conceal your worries and put on your ‘race face’ for your coach, ignoring the niggles, injuries or excessive fatigue, you won’t improve, and they won’t know why – leading to frustration all round. Bullyment has learnt the best way to work with his coach is honestly.

“Feedback is vital. If you can’t finish a session or feel too wasted, you need to be able to adjust your workload and stop digging yourself into a hole. It removes the guilt.”

We’re not saying cycling doesn’t require toughness. The take-home message is, toughness has to be of a calculating kind – not foolhardy obedience to macho myths. Strive to develop mental agility and awareness that comes from mental flexibility – you’ll be able to sustain your cycling career for longer, perform better and stay healthier.

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Cycling Weekly, on sale in newsagents and supermarkets, priced £3.25.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Dr Josephine Perry is a Chartered Sport and Exercise Psychologist whose purpose is to help people discover the metrics which matter most to them so they are able to accomplish more than they had previously believed possible. She integrates expertise in sport psychology and communications to support athletes, stage performers and business leaders to develop the approaches, mental skills and strategies which will help them achieve their ambitions. Josephine has written five books including Performing Under Pressure, The 10 Pillars of Success and I Can: The Teenage Athlete’s Guide to Mental Fitness. For Cycling Weekly she tends to write about the psychological side of training and racing and how to manage mental health issues which may prevent brilliant performance. At last count she owned eight bikes and so is a passionate advocate of the idea that the ideal number of bikes to own is N+1.

-

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much more

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much moreSupported It's not just Bontrager, Balfe's has a huge selection of discounted kit from the best cycling brands including Trek, Specialized, Giant and Castelli all with big reductions

By Paul Brett

-

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-Liège

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-LiègeUno-X Mobility to rebrand as 7-Eleven for Sunday's Monument to pay tribute to iconic American team from the 1980s

By Tom Thewlis