The man who saved my life: How one rider survived a mid-ride cardiac arrest

Saved by a swift-thinking passer-by after his heart stopped dead on a Sunday ride, Rob Burdett wanted to meet up to say thanks

There hadn’t been the faintest warning for Rob Burdett.

He was a fit, clean-living 47-year-old out for a routine Sunday ride with his Cranleigh CC club-mates.

“Apparently, I was climbing up Ranmore Hill, a mild drag I’d done a 100 times before, and I just went” — “apparently” because he has no memory of the dramatic events of that day in March 2015; the entire ride is a blank.

I meet Burdett in a central London cafe — he works nearby as an executive pay consultant — to hear his story as pieced together from witnesses.

>>> Cycling and heart health: should you worry about pushing your heart too hard?

“The group I was riding with saw me come off my bike, as did a guy driving along behind me in his car. I was lucky he did.”

The guy in question was a trainee nurse named Michael Chaplin — or ‘CPR Mike’ to use the nickname he was about to earn.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“He drove past me,” says Burdett, relating Chaplin’s account, “and initially assumed I was a newbie who’d stopped and forgotten to unclip. But he decided to look in his rear-view mirror.”

The scene reflected to Chaplin was a rider on the ground not moving, with bystanders gathering around him.

“The others weren’t giving me mouth-to-mouth because they thought I was breathing, but in fact it was only agonal breath — basically my last gasps.”

Chaplin realised the seriousness of the situation and took control, administering CPR until the ambulance arrived.

Sussing that Burdett was in serious trouble, the paramedics shocked his heart and called in the air ambulance.

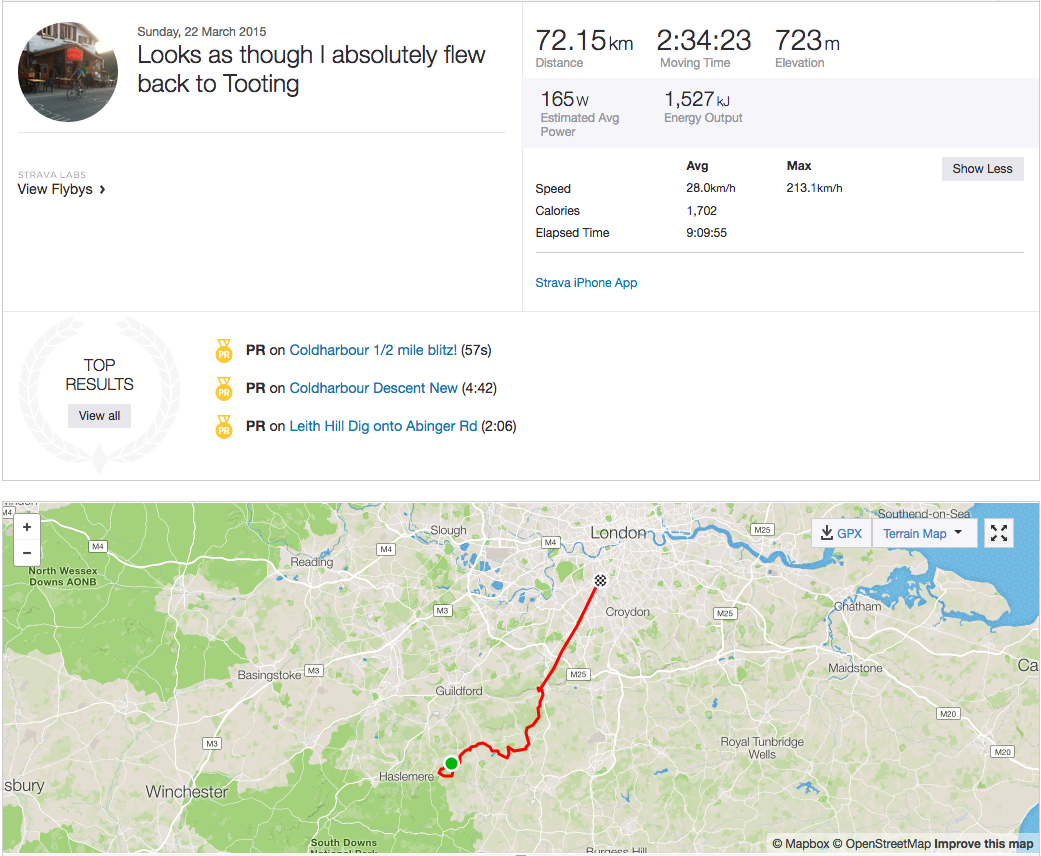

With his phone still recording to Strava, the stricken KOM-hunter was about to log some impressive data: a die-straight line (see picture) from Dunsfold in Surrey to St George’s Hospital, south London, hitting a max speed of 132mph. The first thing Burdett remembers is “coming-to in hospital with a tube down my throat, surrounded by doctors and family telling me I’d had a cardiac arrest.

“I was pretty discombobulated, to say the least. I had imagined having an accident before, but never a cardiac arrest — that was something that happened to other people.”

Still woozy from the effects of medication, Burdett grappled with the new reality now dawning on him.

“Apparently I kept repeating, ‘Cardiac arrest? Bugger me, that’s dramatic!’ I just couldn’t believe it.”

Hospital tests promptly diagnosed a blocked artery — a shock to Burdett, who had assumed his active, healthy-eating, non-smoking lifestyle was keeping him in prime cardiovascular fettle. Two weeks and one double heart bypass later, he was back home.

Speaking to others who’d been with him on the ride, Burdett learned about the decisive intervention of ‘CPR Mike’, whose contact details had been jotted down by a club-mate.

“I sent him an email saying I’d love to meet you but completely understand if you’d rather not.”

Chaplin replied: he would be delighted. They met at a country pub a few weeks later.

“I walked in and there he was sitting in the corner. It was bizarre meeting the person who saved my life.

“I think I asked him whether it was OK to talk about what happened, as I was still trying to piece it together. I must have thanked him 100 times.”

Burdett learned that Chaplin was not only his guardian angel but also a fellow cyclist and kindred spirit — allowing a further gesture of gratitude.

“Mike was made an honorary member of our cycling club, I bought him a club jersey, and we rode together for the first time a couple of months later.”

Remarkably, Burdett was back on his bike just six weeks after leaving hospital.

“On reflection, it was utter madness,” he admits, “but it was that psychological thing, needing to get back on the bike, to put what had happened behind me.”

Doctors reassured him that the bypass had successfully replumbed his heart, medication would guard against new blockages, and he could safely resume his usual riding routine. Burdett has since felt reinvigorated: last year he racked up more miles than ever, including a week-long tour in the Pyrenees and a 5,000-mile fundraiser for the Surrey Air Ambulance (justgiving.com/rh-burdett).

Cycling has gained a heightened significance and he now rides with a redoubled sense of gratitude for the freedom of the open road.

“Whereas before I’d take it all for granted, now when I’m riding along I just think, ‘I’m cycling — I’m not dead; it’s a lovely day, the roads are dry… Bloody hell, this is fantastic!’”

‘I’m no hero, but I knew I had to step in’

Mike Chaplin, 36, was driving to an MTB race when he noticed a rider ahead topple off. He pulled over and leapt into action...

“There were quite a few people already with [Rob] when I arrived on the scene, but they were trying to put him into the recovery position. Although I’m quite a shy kind of person who’d normally sit on the sidelines, in this instance I knew I had to step in. I started doing CPR and carried on for about 10 minutes until the paramedics arrived.

“It was a strange journey to the race after that: I didn’t know whether to go home, pull over and cry or just continue. So I think I did a bit of everything, before deciding it was better to carry on than freak out. In the end, the race didn’t go too badly: I finished second.

“At about 9pm that evening, the phone rang and it was Rob. He said he’d survived the journey and was waiting for surgery.

“Looking back, it’s strange... To say it was a ‘privilege’ might be the wrong word, but it was certainly — regardless of the good outcome — a very emotional experience.”

Would you know what to do?

For a fuller explanation, visit: www.bhf.org.uk/heart-health/how-to-save-a-life

Only eight per cent of patients survive a cardiac arrest, and less than half of bystanders intervene. Rob Burdett was lucky: Mike Chaplin knew CPR and took swift, decisive action. Would you know what to do?

The British Heart Foundation lists six life-saving steps:

- Shake and shout: gently shake the person’s shoulders, ask “Are you OK?” and shout for help.

- Check their breathing. If they’re not breathing, open their airway by tilting their head back and lifting their chin.

- Call 999.

- Give 30 chest compressions.

- Give two rescue breaths.

- Repeat until the ambulance arrives.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

David Bradford is features editor of Cycling Weekly (print edition). He has been writing and editing professionally for more than 15 years, and has published work in national newspapers and magazines including the Independent, the Guardian, the Times, the Irish Times, Vice.com and Runner’s World. Alongside his love of cycling, David is a long-distance runner with a marathon PB of two hours 28 minutes. Having been diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in 2006, he also writes about sight loss and hosts the podcast Ways of Not Seeing.

-

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much more

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much moreSupported It's not just Bontrager, Balfe's has a huge selection of discounted kit from the best cycling brands including Trek, Specialized, Giant and Castelli all with big reductions

By Paul Brett

-

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-Liège

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-LiègeUno-X Mobility to rebrand as 7-Eleven for Sunday's Monument to pay tribute to iconic American team from the 1980s

By Tom Thewlis