Tom Simpson’s World Championships win: 50 years on

Paired with exclusive photography from the Cycling Weekly archive, Chris Sidwells looks back on the year his uncle Tom Simpson won the world title

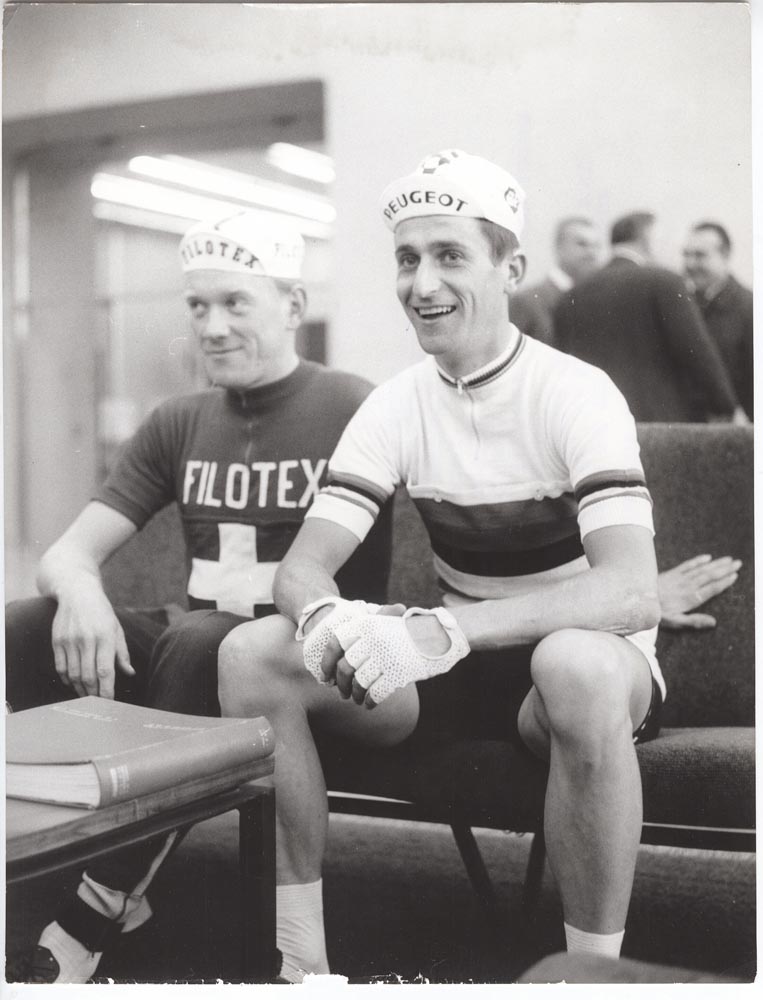

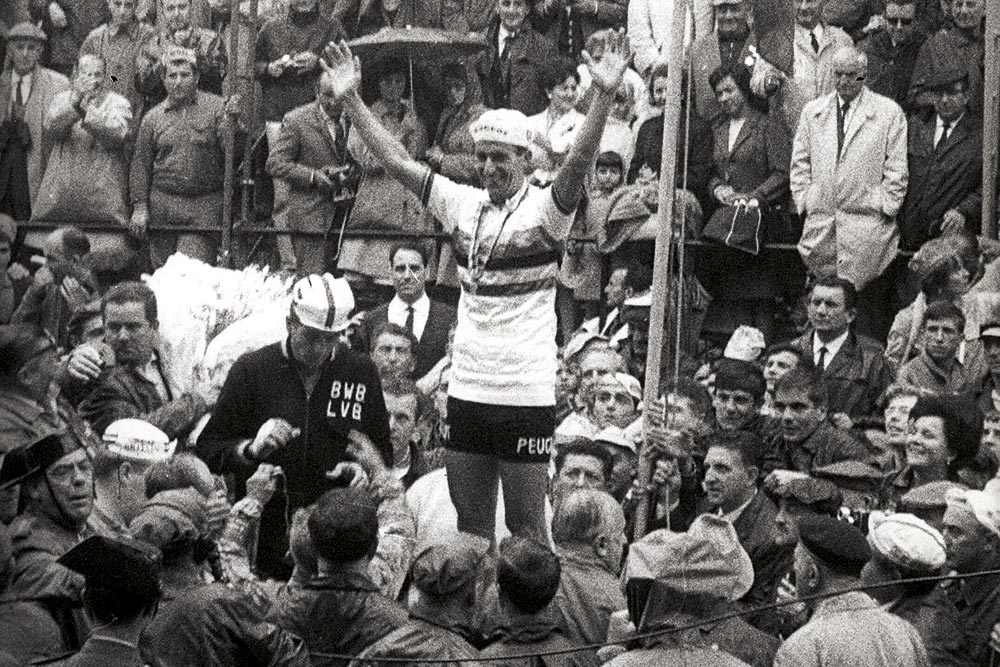

Tom Simpson (Centre)

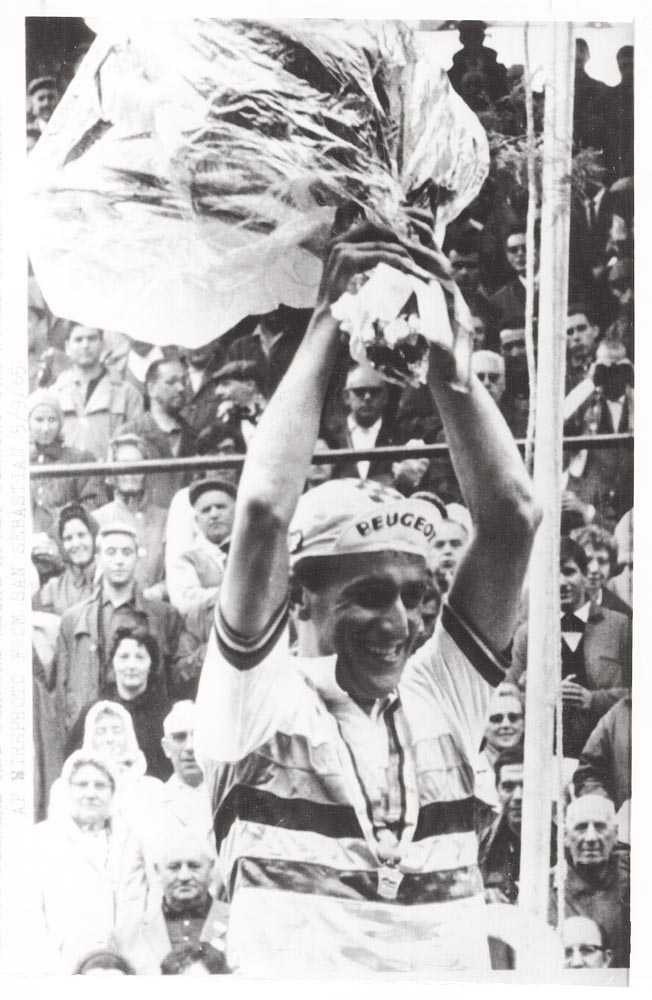

It’s late June 2009 and Britain’s best male road riders start filing into a meeting room at the Celtic Manor Hotel in Newport, South Wales. British Cycling coach Rod Ellingworth is waiting for them. He’s cleared a small area at the front of the room for a DVD player, a big screen TV and something else under a cover. Once the group has settled, the room darkens and some grainy black and white images appear on the TV. It’s a film of Tom Simpson winning the 1965 road race world title.

The group watches in silence. There is no commentary, just clips of the race start, a few shots of famous riders of the day and, towards the end, Simpson and Rudi Altig battling in the rain. It finishes with a delighted Simpson winning the rainbow jersey. The DVD stops, and the lights come up.

As they do, Ellingworth whips off the cover from the mystery item to reveal Simpson’s silk rainbow jersey, the very one he won that day. “Now, who wants to win one of these?” Ellingworth asked. “Hell, yeah!” was Mark Cavendish’s reply, and ‘Project Rainbow Jersey’ was born.

A little over two years later the planning paid off, as Cavendish was crowned world champion after a clinically executed race plan and barnstorming sprint up the finishing straight in Copenhagen. Inspired in no small part by Simpson’s 1965 win, Cav became only the second British winner of the elite men’s world road race title.

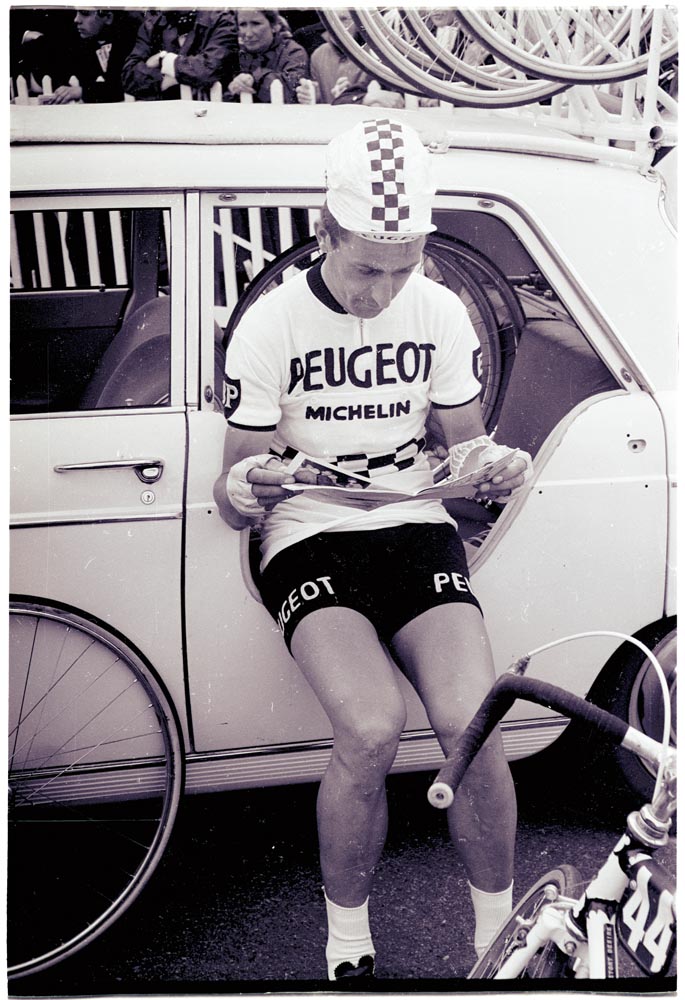

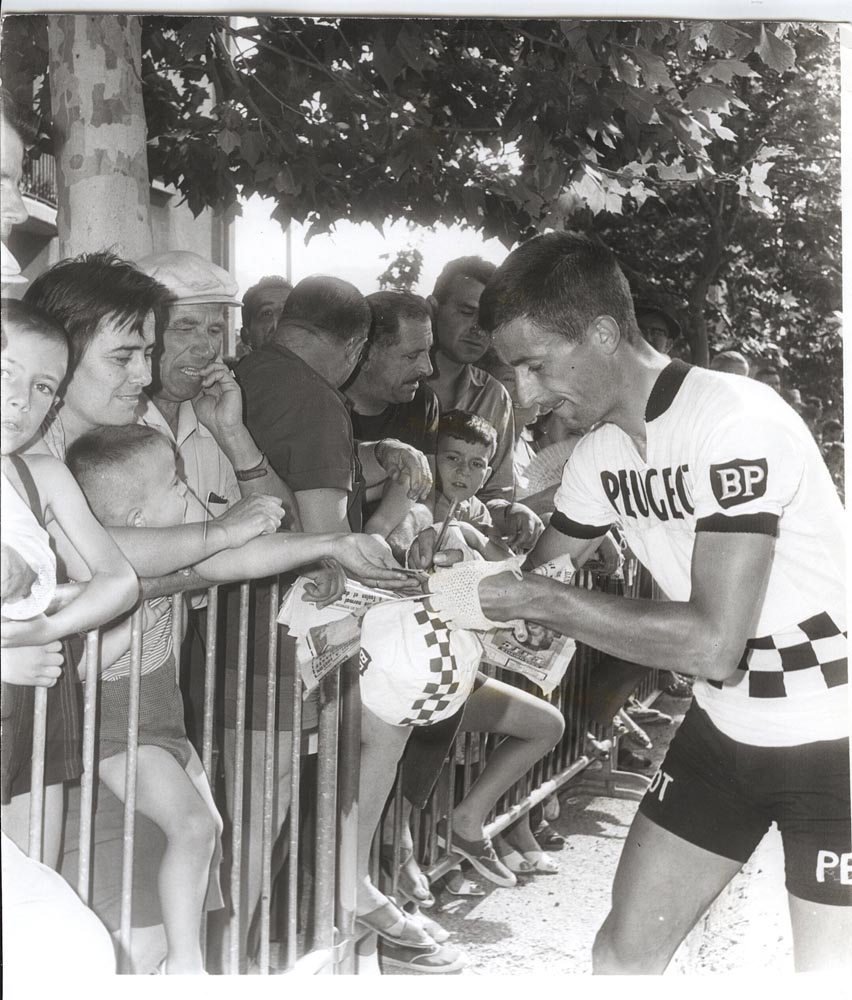

Fifty years on from that win in San Sebastián, Spain, Simpson’s achievement is in no way diminished by the recent success of British riders. ‘Mr Tom’, as he was affectionately known, was Britain’s first pro road race world champion, the first Briton to wear the Tour’s yellow jersey and he won Classics and stage races like Paris-Nice. His career, charm, humour, and his dramatic and controversial death left an impression on British cycling that is as strong today as ever.

Impressive figure

Simpson’s reputation as a snappy dresser, his gift for a one-liner, as well as the races he won, all impressed Bradley Wiggins when he was young. Wiggins is a cycling historian and extremely patriotic; he has a framed Simpson rainbow jersey and a pair of Peugeot shorts among his cycling memorabilia collection.

“I think it’s a shame that the way Tom died has eroded people’s opinion and even their knowledge of what he did,” Wiggins says. “I’ve raced the races he won and his record is amazing. No British rider had done what he did, and he did it virtually on his own. I’d like to see the appreciation of Tom put right.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Simpson grew up in Harworth, Nottinghamshire, an area close to where Ben Swift and Russell Downing now pound the roads. “Being [Britain’s] first [pro] world champion means he’s got a big place in the sport’s history,” Downing says.

>>> Tom Simpson: a life in pictures

“Coming from the same area, and coming from a mining village the same as Tom did, he was always a big inspiration for me,” Simpson’s early career saw him win a team pursuit bronze at the 1956 Olympic Games. But back then, bike racing in Britain was a backwater, an underfunded sport racked with infighting as competing governing bodies fought for governance during a time of political change around racing. When the 21-year-old Simpson went to France with £100 in his pocket, he did it alone.

“Whenever things got tough I read about Tom. I did it a lot when I lived abroad,” 2015 British Elite Road Series winner Steve Lampier says.

“All I had to do was read about him and I’d be inspired and ready to try as hard as I could again.”

David Millar also knows what it’s like to live in another country to pursue a cycling career. “I always felt close to Tom’s story because like him I went to live in a foreign country for cycling. And I made some of the mistakes Tommy made,” he says.

British benchmark

Such was Simpson’s popularity and standing in Europe that for decades he remained the benchmark for British riders heading to the Continent in search of a contract. Graham Jones, a pro with Peugeot in the 1980s says: “Tom was the rider we were always compared with in Europe.”

As the UK cycling industry continues to grow, Simpson’s influence shows no sign of diminishing. British cycling clothing company Rapha has built its multi-million-pound brand on his legacy. Its name is taken from the iconic French St Raphaël team (it later changed its name to Rapha Géminiani due to regulations covering what type of companies could sponsor cycling teams) with whom Simpson signed his first pro contract in 1959.

Rapha’s original Classic jersey was a simplified version of the Peugeot jersey Simpson’s team-mates wore, with black armbands, following his death on Mont Ventoux. That single armband remains a constant feature of Rapha’s distinctive designs.

>>> Rapha pays tribute to Tom Simpson with special edition kit

On the opening stage of this year’s Tour of Britain Rapha-sponsored Team Wiggins riders wore a commemorative red, white and blue jersey to mark the 50th anniversary of Simpson’s world title win (which fell on the same date).

Team Wiggins may be built around its eponymous leader, but the squad is made up of the country’s future track and road stars who, despite their youth, were well aware of the history behind the jersey. That £130 limited edition Simpsonissimo jersey —the Italianisation of the name somewhat clashing with Simpson’s story whose pro career was indelibly linked to French culture — promptly sold out within hours.

Outsider status

It could have all been very different. Despite two previous fourth place finishes at the Worlds, Simpson wasn’t tipped by the press to win the 1965 race. He’d been forced out of that year’s Tour de France after a crash and a damaged hand brought about a serious blood infection that could have seen his left arm amputated. After a short rest period he was back on his bike and soon returned to racing, but, unbeknown to many, tailored everything to his Worlds attempt.

The British team he led was, however, small, and, compared with Europe’s bigger cycling nations, not particularly strong. Simpson was joined by Barry Hoban, Vin Denson, Michael Wright, Alan Ramsbottom and Keith Butler, most of the British pros based in Europe at the time. They would line up against eight-man teams from the main European nations.

Despite the odds being stacked against him, there was no lack of support in his adopted home of Ghent, in northern Belgium. This is where Simpson lived with his wife Helen during the best years of his career. As a top pro, and especially as a Tour of Flanders winner, he was a local celebrity. Helen, now Helen Hoban, was watching the Worlds on TV in the couple’s home in Sint-Amandsberg, a north-eastern suburb of Ghent, with friends and as the race went on she noticed the audience was growing.

“The house was filling up with people, some I didn’t even know, and I was rushing outside to tell my neighbours what was happening, then back to the TV,” she remembers. “I don’t know how many turned up and were watching with us, but the house was packed. And when Tom won; well, there was one guy, a young English rider, he jumped, up fell back down and broke the sofa.

“Everybody was so happy. It was unbelievable. And then flowers started arriving at the front door. I quickly ran out of vases to put them in.”

And if it was mad in Ghent it was pandemonium in San Sebastián. All of the British riders, except for Michael Wright, finished the race. Vin Denson was 53rd across the line, but what he remembers most was “riding towards the finish listening to the radio coming through the open window of one of the journalists’ cars following the race, and that’s how I heard Tom had won”.

As soon as Simpson had the rainbow jersey on his shoulders he was signing contracts to ride criteriums and track meetings all over Europe. He had a quick glass of champagne with the British team then headed for a flight to Paris for a criterium the next day.

Left luggage

In the rush Simpson left his bag with his rainbow jersey and medal in it with the rest of the British team’s luggage. They were later reunited, but in the meantime he was lent a rainbow jersey by outgoing world champion Jan Janssen, who says: “I was pleased to see Tom as world champion; he was a very special person, a talented rider who was always smiling, always joking. I had some of my best times in cycling with him, and I missed him a lot after he was gone.”

Back in San Sebastián the British team celebrated winning the country’s first world pro road title quietly. “We just had a meal and relaxed a bit,” Denson says. “It was a good feeling, and I am proud to have been part of it, but it would have been nicer if Tom had been there with us. I still miss him, and when he died it changed everything for me. I lost my will to be a pro rider.”

On a happier note, Denson has a story from that evening he really enjoys telling: “There were these two old English ladies, quite posh. They were doing a Tour of European cities and resorts. The organisers of the Worlds put on a firework display to celebrate the end of the event, and I’ll never forget overhearing those two old dears. One of them asked the other, ‘What is everybody celebrating?’ And her friend replied, ‘It seems that a young man from Doncaster has won the annual fireworks competition, dear.’ Tom would have loved that,” Denson remembers.

Going home

Next day the British team split up and made their way home, with Barry Hoban driving Simpson’s car: “Tom loved his cars and he’d just bought a BMW 1800 Ti/SA, the TI stood for Turismo Internationale, and they were performance cars used in touring car races. So I had this lovely fast car to drive through the top of Spain and up through France to Paris, where Tom met me outside the Gare du Nord. I handed him the keys and he jumped in and he tore off up the road to get to a reception in Ghent.”

Helen Hoban remembers what happened next: “Almost as soon as Tom got home a crowd of people turned up in front of our house. There were so many people Tom had to go to an upstairs window, so they could all see him. He was in demand everywhere. He got the freedom of Sint-Amandsberg.

"His mum and dad came over for that and we were driven through town in an open carriage. By that time Tom had won the Tour of Lombardy as well. I went to Italy and saw him finish at the track in Como. It was wonderful. But no sooner was that done than he was riding six-days all over the place.”

Simpson was a big star. His Lombardy victory was very impressive. Just like Fausto Coppi, the Italian papers said. By the end of the road race season he was second in the Super Prestige Pernod competition, which served as the world rankings. Jacques Anquetil won it, and it was the second time Simpson had been runner-up to the five-time Tour winner.

World champion, twice ranked number two in the world, Classics winner, Simpson was now a major star in what was a high-profile European sport. But there was something that made him bigger: his Britishness. And no, it wasn’t just because he dressed up for photo shoots in a ‘gentleman about town’ sharp suit, bowler hat and rolled umbrella.

>>> Chris Froome overtakes Tom Simpson in Cycling Weekly’s All-Time British Ranking

Simpson had done that since he moved to France in 1959, but now there was a new Great Britain. A country of The Beatles, fashion and pop culture, a Britain that was cool and trendy. Simpson was seen as part of that in Europe and was even invited by one French radio channel to try his hand at being a DJ.

News of his stardom in Europe finally reached the UK, where it captured press interest and people’s imaginations. Simpson was awarded the Daily Express ‘Sportsman of the Year’ trophy, which Helen accepted on his behalf because he was busy winning the Brussels Six-Day. Then he won the Sportswriters’ Association award, where the trophy was presented by the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson.

Media star

Simpson started his acceptance speech with, “Mr Prime Minister, we are both in the saddle, you at Number 10 and me on my bike, but I hope your bottom doesn’t hurt like mine does.” Then he told a joke that went down very well then, but would cause apoplexy in today’s press...

“One day at Doncaster races the Duke of Norfolk was casting a patrician’s eye over proceedings when he saw a trainer feeding something to a horse. ‘What’s that, my man?’ the Duke inquired. ‘Just a sugar lump, my Lord. I’ll eat one myself, and you can try one if you like,’ the trainer replied.

And the trainer ate one and the Duke ate one of the sugar lumps, and off he went satisfied with the explanation. Later on the trainer was giving his jockey his final briefing, when he said: ‘Look, keep her reined in at first lad, then with two furlongs to go let her have her head, and if anybody passes you don’t worry, it will either be me or the Duke of Norfolk.’”

The final accolade was the BBC Sports Personality of the Year award, and Simpson was not only the first cyclist to win these awards, he was the first person in history to win all three big British sports awards in the same year. Princess Anne was the next, in 1971.

“There had been hints Tom would win,” says Helen Hoban. “David Saunders, who wrote for the Daily Telegraph and who was a friend of ours kept saying, ‘You know, Tom could have won this, be prepared.’ And he did. Somehow, though, he’d managed to have a car accident on his way to the presentation. I wasn’t with him, we’d gone separately, but he turned up with a cut on his forehead.”

Cycling in the UK was on a high. It was a minority sport with hardly any TV time and few column inches. But after Simpson’s Worlds triumph the People published a series of long interviews with Simpson in which he was far too candid about the ways of the peloton for some of his European colleagues. Many other newspapers told his story at length and the BBC visited Simpson during the Brussels six-day for an interview which aired on Saturday afternoon Grandstand. And in January 1966 Simpson was even invited onto Desert Island Discs, another first for a cyclist.

British cycling had never felt so good and countless young hopefuls went to live in Ghent to race in the tough school of Belgian kermesses — something they still do to this day. Simpson built the Velotel Tom Simpson to act as a base for them and he was talking to British businesses about sponsoring a British pro team to ride the biggest races.

Simpson changed cycling in this country, not just as world champion and his other achievements, but also through his style and charisma. Following his death on Mont Ventoux in 1967 the impetus went out of British cycling and it took decades for it to recover.

Despite the barren 50 years between British male world champions on the road, Simpson’s legacy is as strong as ever, his influence reborn with the current golden generation. What he achieved and the way he achieved it was remarkable and will be remembered forever.

Watch: Show us your scars - best of 2015

The reign in Spain

The 1965 pro Worlds used a hilly 12-mile circuit around a small town called Lasarte-Oria, just south-west of San Sebastián. The circuit was ridden 14 times and, as happens quite often in northern Spain, it rained. “Once we all got there Tom had us out at eight o’clock in the morning. It was pouring with rain but he wanted to ride the circuit to get to know it. We did a few laps then went off for a loop in the hills, and Tom was flying,” Vin Denson remembers.

This was very much Simpson’s team. “We stayed at the British team’s hotel, but we paid our own way, and Tom supplied us with some Great Britain jerseys that he’d had made in Italy and paid for himself,” Barry Hoban explains. “The British team used Raxar jerseys, which were awful to wear. The jerseys Tom had were really nice, made of soft wool.”

Ninety-six riders started the race, and the British team had a plan. “The night before Tom asked me to go with any breakaways, but not to work with them. Then if a move looked promising he said he’d try to get over to it, and that’s when I should work,” Hoban says.

“I had a hellish first year as a pro when my team manager Antonin Magne made me ride everything from Paris-Nice and the cobbled Classics, through two Grand Tours, right up to the Tour of Lombardy. By then I was knackered, and that feeling persisted through 1965 but I was going better by September and Tom knew it.

“Every day in the 1964 Vuelta I’d seen the Spanish and Portuguese riders attack from the start. More often than not you scraped them up before the finish, but they still kept attacking, and they attacked in San Sebastián.”

Attack

Hoban covered the attacks, which developed into a breakaway. But then Roger Swerts of Belgium and the Dutch winner of the 1964 Paris-Roubaix, Peter Post, caught the breakaway. Then Franco Balmamion and Bruno Mealli of Italy, and Karl-Heinz Kunde of Germany joined.

This was promising. Post, Balmamion and Swerts were favourites. Information filtered back to Simpson. “Tom asked me and Alan Ramsbottom to take him to the front, then attack. He wanted us to do a turn each, like in a lead-out for a sprint, which is what we did,” Denson says.

They launched Simpson clear. Rudi Altig of Germany saw what was happening and sprinted after Simpson, and the two began working together. They quickly caught the front group, and that was Hoban’s signal. “Now I started working. Tom was working, Post, Altig and the Spanish riders were all working, plus some others,” he says.

The group started to pull away from the peloton. Ward Sels of Belgium and Frenchman Jean Stablinski tried to get across, but their move failed.

Great day

Jacques Anquetil tried to organise a chase. “But nobody would work with him, so Anquetil did a whole lap on the front of the bunch,” Keith Butler explains. “I sat close behind him, and the pace was incredible, but after a lap he’d made no impact on the lead, so he stopped riding. I felt like I’d played a part in what was a great day for British cycling.”

As the race wore on the size of the front group, and an increasing number of passengers in it, started worrying Simpson. “I knew Tom was going to go,” Hoban says. So did Altig.

>>> British cycling legend Barry Hoban launches autobiography

“I knew Tom, I knew he was good,” Altig says. “I knew he would attack, too; it was in his nature. And I could see he was going well, so I waited and I watched him. I thought if we got clear we could stay clear and, if I could hold him on the hills, then I would win the sprint.”

Simpson made his move on a climb. It wasn’t a steep one, but it was quite long and it was followed by a stretch of false flat — the perfect place for a strong rider to go.

“I was riding so well that day I didn’t think I could be beaten in a straight fight,” Simpson said afterwards.

“I was concerned about the riders who weren’t working in the break, so I needed to do something. In the end it was Rudi Altig who came with me, but it didn’t change a thing. I still knew I would win.”

“We agreed to work together until one kilometre to go, then we would decide the race,” Altig says. And so it proved. They separated 1,000 metres from the line — Simpson went first, got a gap and Altig couldn’t close it. His legs went. “I fractured my hip earlier in the year and I was short of training and competition, otherwise maybe I could have won the sprint. It didn’t matter though, because next year I was world champion,” Altig says.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast

-

'I'll take a top 10, that's alright in the end' - Fred Wright finishes best of British at Paris-Roubaix

'I'll take a top 10, that's alright in the end' - Fred Wright finishes best of British at Paris-RoubaixBahrain-Victorious rider came back from a mechanical on the Arenberg to place ninth

By Adam Becket Published

-

'This is the furthest ride I've actually ever done' - Matthew Brennan lights up Paris-Roubaix at 19 years old

'This is the furthest ride I've actually ever done' - Matthew Brennan lights up Paris-Roubaix at 19 years oldThe day's youngest rider reflects on 'killer' Monument debut

By Tom Davidson Published

-

UCI Road World Championships 2024: Elite women's and men's time trial start times

UCI Road World Championships 2024: Elite women's and men's time trial start timesThe full rider lists and start times for the individual time trials in Zurich

By Tom Davidson Published

-

Jorgenson and Faulkner to lead a strong Team USA at UCI Road World Championships

Jorgenson and Faulkner to lead a strong Team USA at UCI Road World ChampionshipsThe 2024 UCI Road World Championships are held in Zurich, Switzerland, September 21-29

By Anne-Marije Rook Published

-

‘Unprecedented’ television audiences revealed for cycling Super Worlds

‘Unprecedented’ television audiences revealed for cycling Super WorldsFans around the world watched more than 200 million hours in August

By Tom Davidson Published

-

Team USA at Road Worlds: Are Powless and Dygert our best hopes for a medal?

Team USA at Road Worlds: Are Powless and Dygert our best hopes for a medal?Here's who we'll be watching in the rainbow battles in Glasgow, Scotland.

By Henry Lord Published

-

Glasgow UCI World Championships bags Lidl partnership

Glasgow UCI World Championships bags Lidl partnershipSupermarket chain becomes official fresh food partner for the championships taking place in Glasgow in August

By Tom Thewlis Published

-

Ukrainian cyclist disqualified from World Championships after blood sample result

Ukrainian cyclist disqualified from World Championships after blood sample resultMykhaylo Kononenko's blood sample revealed the presence of the banned substance tramadol

By Tom Davidson Published

-

How many calories do you burn winning the World Championship road race?

How many calories do you burn winning the World Championship road race?It’s the equivalent of six margherita pizzas, according to Remco Evenepoel's Strava data

By Tom Davidson Last updated

-

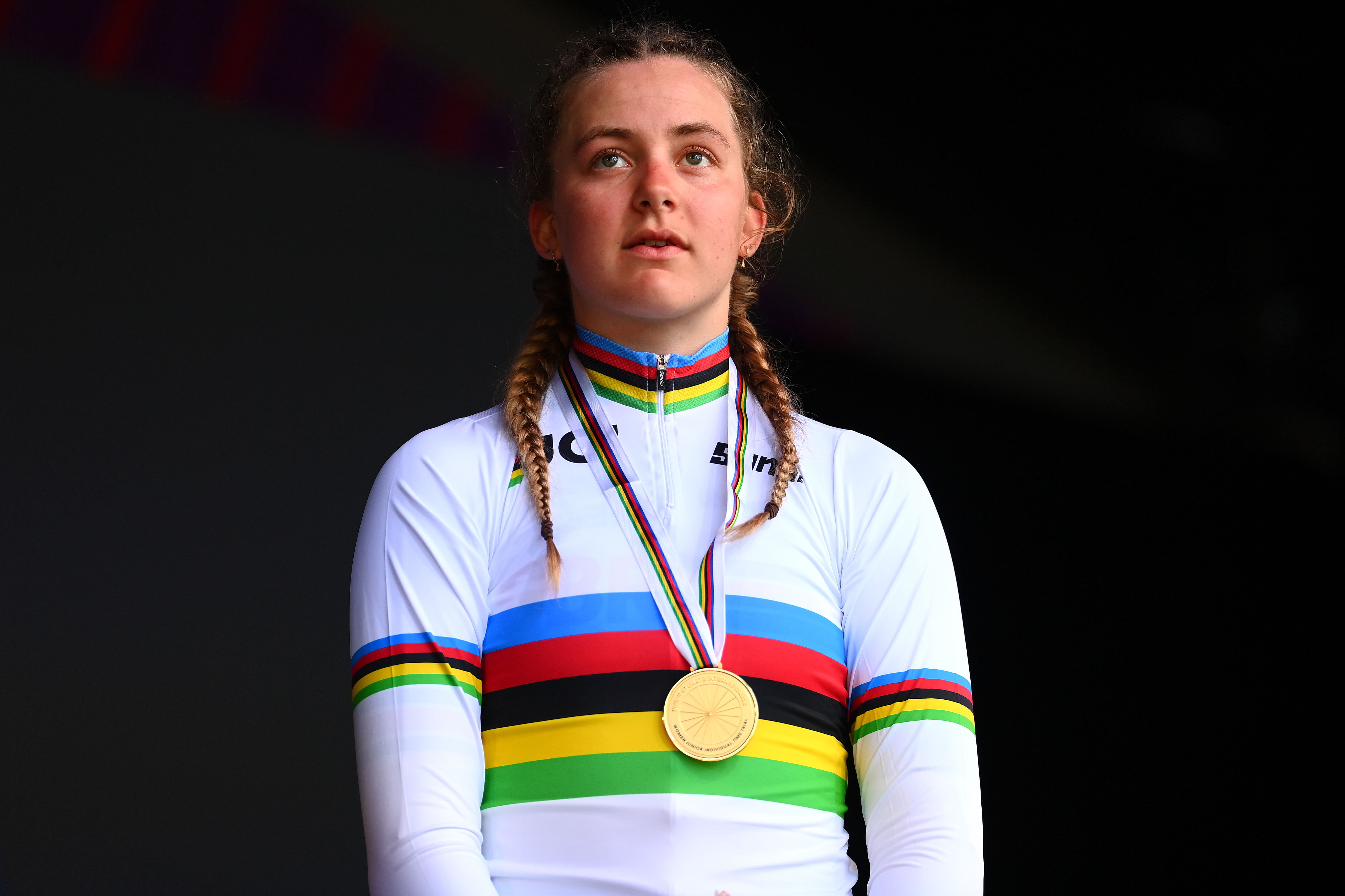

Don’t expect too much from Zoe Bäckstedt, says teenager’s British Cycling coach

Don’t expect too much from Zoe Bäckstedt, says teenager’s British Cycling coachJunior academy coach Emma Trott has warned against piling pressure on the 18-year-old

By Tom Davidson Published