What counts as good for your age?

There is no avoiding the fact that cyclists slow down as they grow older, but what counts as good for your age, and how can you stay faster for longer? David Bradford goes in search of age-related gold standards

(Daniel Gould)

Earlier this year, we received an email with the subject line: ‘How good are you?’. No, it wasn’t a phishing attack; it was a genuine enquiry from a reader named Alex. To our relief, Alex wasn’t getting in touch to conduct an audit of CW staff FTPs or Zwift rankings. Instead, he was asking a serious question related to cycling performance and age.

“We all want to know how our numbers stack up against club-mates and pros, and we’ve all studied the Coggan watts-per-kilo table,” he wrote, “but for cyclists of a certain age, these comparisons are difficult. We’re missing comparative statistics within our own cohort.”

It was a good question: how to benchmark your performance against your cycling peers? I immediately thought of the age-grading system used in running – a formula that calculates your performance as a percentage of the world-best for your age. In lifetime-best form, aged about 30, I’d hit around 82 per cent. These days, nearing 40 and comparing my ever-slowing times with super-veterans like the USA’s Bernard Lagat (5k in 13:38, aged 41), my age-graded score has plummeted, but it’s still an interesting yardstick. Cycling has no such system; in road racing, the reason why is obvious – there are too many variables. But in time trialling, there is nothing preventing us from comparing performances across the ages just like runners do.

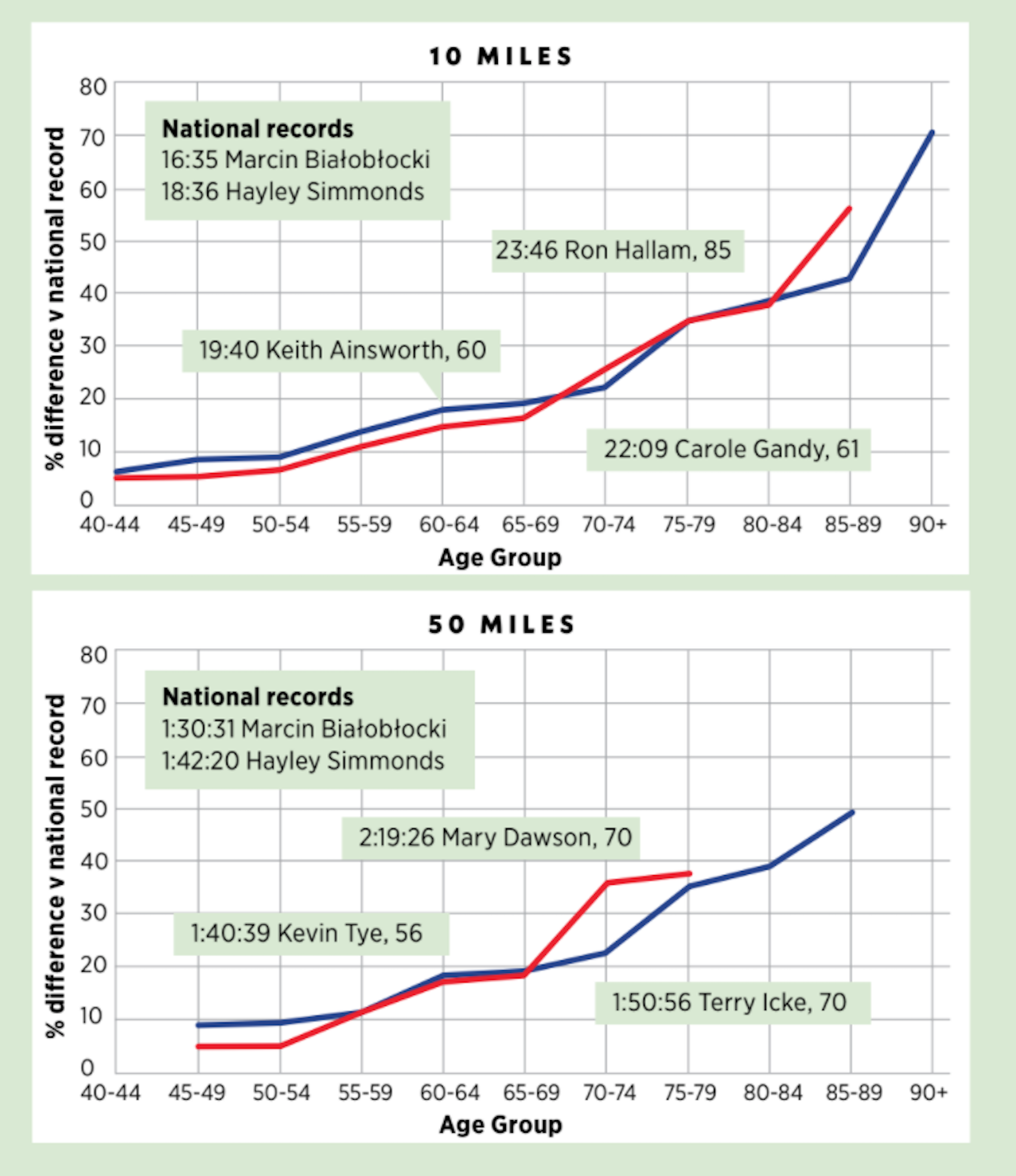

The graphs below show the percentage slow-down through the age groups, comparing the veteran record with the national record, for 10-mile and 50-mile time trials – the blue line is men, the red line, women. As you would expect, older riders fare better (relatively) in the longer event; the fastest veteran man over 50 miles is Stephen Irwin, who in 2016 aged 45 clocked 1:35:13 – which is just 5.21 per cent slower than Marcin Białobłocki’s national record. Over 10 miles, the difference is a full 7.24 per cent – James Rix’s 17.47 at age 41, trailing in the wake of Białobłocki’s 16.35 national record.

It’s difficult to choose the most gob-smacking performance from the VTTA’s meticulously-maintained records. Most of them defy not only the age of the riders, but belief, too – by what immortal powers does an 85-year-old man ride 10 miles in 23.46? That’s over 25mph! Or a 60-year-old woman ride 50 miles in 1:59.47? Have these riders worked out how to stop the ageing process in its tracks? What are their secrets?

The scientific view

I wanted to speak to some of the record-setting veterans whose pedalling power defies their years to find out how they have maintained such a high level of performance, but first I needed to better understand the correlation between ageing and performance from a scientific perspective. Professor Christopher Minson from the University of Oregon, USA, has a special interest in the effects of ageing on cardiovascular fitness. The first factor he draws attention to is VO2 max (the body’s top-end rate of oxygen uptake) – which tends to decline by around 10 per cent per decade after the age of 30.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

>>> Subscriptions deals for Cycling Weekly magazine

“We need to look at what determines VO2 max. It’s your max heart rate, max stroke volume [of the heart], max ability to get oxygen into your blood and the max rate of getting it out of the blood and into the muscle. The biggest factor is a progressive decline in maximum heart rate,” says Minson.

It’s a simple pumping problem: fewer heart beats per minute means less blood, and so less oxygen, getting to your muscles. The good news is that athletes who continue training as they age tend to have a much slower decline in maximum heart rate, preserving their VO2 max.

The muscle itself also changes, Minson explains. “As you age, you get a shift towards slower-twitch fibres, with fewer type-IIX fibres – the type for repetitive bursts of speed. This not only means you’re less able to continually generate speed, but it may also contribute to the fall in VO2 max.”

We all know that muscle mass gradually decreases with age, but changes in muscle composition also play a part. “It may be that, with this change in fibre type, your body has to call into action more muscle cells to achieve the same output as before – and this added recruitment may equate to a feeling of greater exertion.”

There is also evidence, Minson continues, that with age comes a decrease in the “satellite cells” responsible for signalling muscle degeneration so as to prompt recovery. “Training is always a process of breakdown followed by synthesis – building back stronger. There is debate on whether the main factor in older athletes is the breakdown speeding up or the synthesis slowing down.”

Minson’s personal view is that these factors vary between individuals and between sports; each athlete ages in different ways at different rates. Regardless of these nuances, the message for veteran athletes is clear: you need to adapt your training to match your changing capacity to recover.

“As we age, we have to be thinking much more about training really smart,” says Minson. “I spoke to a coach who has looked at the data of a large number of athletes and noticed, among those in their 50s and 60s, a much higher rate of failure in the latter part of sessions when attempting repeated intervals.”

It’s not only post-workout recovery that declines, but also the ability to recover within workouts.

“There is an impact at micro and macro levels, and so you need to work out how much stress you can tolerate within a given session, as well as within a given week or training cycle.”

Bear in mind too that as you grow older, your body’s endocrine system is dialled back, often reducing the levels of hormones such as testosterone, aldosterone and growth hormone – all of which can have a serious effect on energy levels and recovery. For women, the menopause brings a rapid and precipitous drop in sex hormones, sometimes requiring replacement therapy.

Performance longevity

I’m curious to know whether a cyclist is like a car in the sense that performance decline correlates to mileage. Do the repeated training cycles, year after year, gradually wear us out – in other words, do we have a ‘performance shelf life’?

“The data isn’t clear,” says Minson, “but cyclists are better off than runners in this regard, being subject to far less wear and tear. If you can avoid damaging yourself in crashes and avoid patellar problems, then I really think the experience and knowledge of your body that you accrue can help you stay fitter for longer.”

One note of caution concerns heart health: athletes are more prone to abnormal heart rates (arrhythmia) as they age, possibly caused by scarring in the heart. “I suspect that the people who account for most of these cases are the ones who have overtrained over a long period of time,” says Minson. “For the smart ones who are managing their training loads, fatigue and recovery, there is no firm evidence that they’re at a heightened risk.”

Meeting the super-vets

It’s time to speak to someone who puts the theory into practice. In the 55 to 60 age group, no woman has gone faster over 10 or 25 miles than 60-year-old Sarah Matthews. Two years ago, aged 58, she clocked 21.33 for 10 miles and 55.24 for 25 miles – impressive to say the least. It comes as a surprise, therefore, to learn that just one year earlier, Matthews almost quit the sport.

“Three years ago as my winter training was ramping up, I just couldn’t seem to hit my goals. I was beginning to think, ‘I’m too old for this, I need to give it up.’”

What changed her mind?

“I’m coached by Chris McNamara [TrainSharp] and, after I sent him a long, long email, we had a chat and he said, ‘I just don’t think you’re eating enough carbohydrates.’”

Matthews explains how she had been avoiding carbs during the evening, in solidarity with her husband who was trying to lose weight, then training in the morning, unwittingly in a depleted state.

“Within a fortnight of changing my eating habits, I was back to normal. It was that simple.”

There are two clear lessons here: first, beware low-carb training and only do it in a very cautious, controlled way – sedentary older people may need fewer calories, but the priority for older athletes is to fully and properly fuel every ride. Second, if you are struggling to hit your training targets, do not presume the reason is your age. Ageing is a slow, gradual process. If your performance has declined dramatically from one year to the next, there is probably an underlying physiological cause and it could be something as simple as fuelling.

Another surprise from Matthews is that she didn’t buy her first road bike until winter 2010, at the age of 51. “I’d done a lot of running,” she says, “but I’m not a fast runner – at 5ft 9in and 65/66kg, I just don’t have the ideal frame for it.”

A foray into duathlon saw her qualify for the age-group world championships, and when a running injury struck in 2015, the logical step for Matthews, who lives in Haslemere, Surrey, was to join the local cycling club, a3crg, and focus on the bike.

“To cut a long story short, I filled in an online form to sign up with TrainSharp... Next thing I know, I’m in the pain cave, having bought a power meter, and I’m on the journey.”

That journey has conveyed Matthews to countless wins and TT domination among over-55s. What changes to fitness has she noticed as she has grown older?

“One really noticeable thing is that now, if I don’t do any weights for a couple of weeks, I really notice it during the first session back.” Matthews describes the loss of muscular strength as seeming to occur much quicker than before, which she combats by simply keeping up her gym habit consistently – and being cautious when returning after a break.

“The other thing is fatigue – not sleepiness, but getting on the bike, getting up to threshold and my legs going, ‘Uh-uh, not today!’ I’ve learnt how to recognise that feeling and manage it.”

Matthews has a biology degree and is consciously “body-aware” – when her legs cry ‘no’, she listens. That means no longer attempting to race twice in a weekend.

“If I want good legs, the trick is to not do anything the day before. I really notice the difference now, whereas before I was able to get away with it.”

Another adaptation has been factoring in the effects of getting to and from races.

“Travelling completely wrecks you,” says Matthews. “The body produces the stress hormone cortisol and it tires you out – I wouldn’t have noticed that at a younger age.”

Her solutions to the evolving needs of her maturing body are often simple: build in more travel time, eat more carbs, don’t race on consecutive days, take one day off at the weekend for recovery and family time, and have a lie down after long rides. They’re all common-sense measures, but they speak of a clear-headed acceptance of the realities of ageing – facing the facts and thereby minimising the slow-down.

In concluding our chat, I remind Matthews that the 60-to-65 records are dominated by Carole Gandy, who clocked 22.09 for 10 miles aged 61 and, even more impressively, 56.30 for 25 miles aged 64.

“I just need to slip under 22,” says Matthews, letting slip an additional target. “Nobody in their 60s has gone sub-22 minutes. I am going to be that person.”

Still breaking records at 90

One of the most jaw-dropping records in the VTTA lists is 23.46 for 10 miles at the age of 85. I want to speak to the man himself: veteran TT legend Ron Hallam, now 90 and still breaking records. I catch him just as the heavens open.

“I was about to go out on my bike, but now it’s tipping down.”

The weather has granted us time to chat – and he starts at the beginning. Cycling began for him with the CTC, long-distance rides as a teenager in Derbyshire and, from the age of 16, as a means of commuting to work.

“There was a local club reforming after the war in 1947. That started it off – they started holding evening 10s.”

By the 1960s, Hallam was competing regularly and had got his ‘25’ PB down to 1hr 1min – only five minutes shy of the then comp record. He reminds me repeatedly of the technological differences between then and now.

>>> Cycling Weekly is available on your Smart phone, tablet and desktop

“You had two gearing choices: fixed wheel or Sturmey Archer. Anyone serious about racing was on fixed.”

He won the Welsh national 25 in 1965, having started training seriously with a small group of ambitious amateurs, including triple 25-mile champion Gordon Ian. Then, in 1967, Hallam rode a very nippy ‘100’, 4hr 10min – still on fixed.

Are any of his team-mates from back then still racing?

“No, I’m the only one,” he pauses. “In fact, there are only two or three [over-90s] in the whole country.”

What has allowed him to go on training and racing decade after decade while almost all the others have either retired or died?

“Determination comes into it. Being a fixed wheel rider comes into it, again, because the comparatively low gearing means you can spin forever. And never a lightweight bike.”

Aside from small gears, there is no skirting around the whirring cogs of time and fate.

“You’ve got to be lucky, up to a point, with your health,” Hallam acknowledges, “but you’ve also got to be careful.”

He suspects that some veterans, nostalgic for simpler times, are put off by the arms race involved in modern time-trialling. Does he himself invest in the latest tech?

“Oh no. In the 75 to 90 age group, there is nobody I need to buy a good bike to beat.” He isn’t boasting, it’s just a fact. “They all have the usual problems; very few are lucky enough to be able to carry on at the same level.”

Giving it some beans

I’m keen to drill down into the detail of maintaining race-level fitness beyond ‘four score and 10’: surely the training gets harder?

“Not really,” says Hallam, “but as you get older, you don’t bounce when you crash. You avoid riding in foul conditions in the winter and ride the turbo instead.” Astride the turbo is where he would be right now, if he wasn’t talking to me.

He talks me through a typical week: race on Saturday, recovery ride on Sunday, 30 or 40 miles on Monday, turbo on Tuesday, social ride on Wednesday, then two more rest days ahead of Saturday’s race.

“About 120 miles a week.” He emphasises the importance of the rest days by way of comparison. “I’ve got a friend who’s 75 and goes out every day – and he can’t understand why he doesn’t improve!”

Hallam describes his turbo sessions as “harder than racing”. Judging his effort with a heart rate monitor and “a big clock on the floor”, he goes up through the gears until his heart rate hits his max – nowadays 140bpm – then back down again.

“As long as your heart is sound and strong, you can’t do any harm.”

He is determined to keep pushing hard, because with every year older comes a new set of records to claim.

“The over-90 record for 10 miles, which I’ve got to beat, is by a bloke named Syd Wilson. He’s done a 28.24.”

This year’s record-targeting preparation was going well until February when, ironically enough, Hallam was injured by a cycling trophy. Having agreed to help out with a local club’s record-keeping, he was collecting a cup to be engraved when he knocked his leg on a box.

“It made a great hole in my leg,” says Hallam, “which ended up getting infected, and I had to have the dressing changed every day for three months. Eventually, it cleared up.”

With his leg healed, the peerless nonagenarian is back in action – and I’d better not keep him much longer, as he is itching to jump on the turbo. Before he does, I want to know whether he has any special nutrition rules or beliefs.

“Oh yes, I have chips, biscuits, cakes… Chips once during the week, and when I get home after a race, a couple of chip butties. I don’t eat Italian, Indian or any takeaways, only McDonald’s.

Other than that, I’m very strange about my eating.”

Strange in what way?

“The only vegetables I eat are potatoes and peas. When we go out to dinner, we take peas with us in a thermos flask.”

He suspects his spartan tastes were ingrained during the post-war rationing years. As for booze, “I’ll have a whiskey on a freezing-cold night, nothing more.”

I put to him that his methods could be summarised by the slogan: all things in moderation except peas.

“That’s right!” Hallam laughs. “Garden peas, mushy peas, any peas. And beans – that’s what I have before a race, beans on toast.”

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Cycling Weekly, on sale in newsagents and supermarkets, priced £3.25.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

David Bradford is features editor of Cycling Weekly (print edition). He has been writing and editing professionally for more than 15 years, and has published work in national newspapers and magazines including the Independent, the Guardian, the Times, the Irish Times, Vice.com and Runner’s World. Alongside his love of cycling, David is a long-distance runner with a marathon PB of two hours 28 minutes. Having been diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) in 2006, he also writes about sight loss and hosts the podcast Ways of Not Seeing.

-

Fizik Tempo Argo R3 Les Classiques saddle review: comfort both on and off the cobbles

Fizik Tempo Argo R3 Les Classiques saddle review: comfort both on and off the cobblesObscured beneath the special edition ‘mud flecks’ is one of the most comfortable short-nosed endurance saddles on the market

By Simon Fellows

-

Mike's Bikes 'mega sale' is live and site wide with discounts over 50%

Mike's Bikes 'mega sale' is live and site wide with discounts over 50%Running until Sunday all products are discounted including complete bikes, clothing, smart trainers and much more

By Luke Friend