Our man in the bunch 5: the Tour de France

Cycle Sport’s Our Man in the Bunch series ran through the 2012 season, to popular acclaim. An anonymous professional rider sent us a series of dispatches from the peloton, covering all subjects from money, through media to management and more. We reproduce the series here.

Words by Our Man in the Bunch

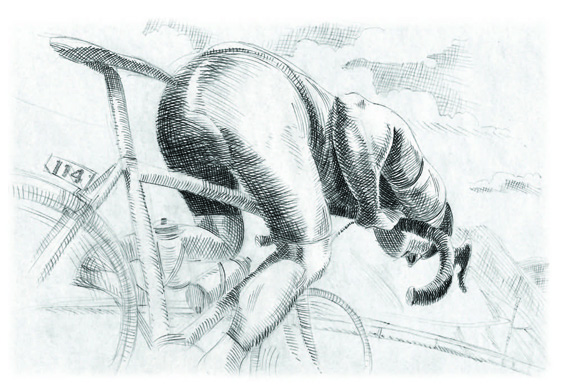

Illustration by Simon Scarsbrook

This article originally appeared in Cycle Sport Summer 2012

A lot has changed in cycling over the last decade or two. But there’s one thing that’s constant: the Tour de France.

It towers over everything else in the calendar, for fans and riders. It’s a pressure-cooker for the staff, management, sponsors, press and everybody else involved, including us riders.

The magnitude of the event is evident as soon as we arrive, normally the Tuesday or Wednesday before the start. Press conferences seem three times the size, and sponsors and VIPs make a sudden appearance from the woodwork. All of a sudden, it’s the general public who want to take pictures and have a chat with us, not just the slightly over-enthusiastic autograph-collectors who are the only spectators we see at the lesser European races.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

That final lead-up to the first stage seems to last an eternity. As if I need anything more to heighten the nerves, three days consisting of team meetings, course recces, TTT practice, interviews with journalists, team presentation, etc, is enough to throw me over the edge. Finally arriving at the start ramp or kilometre-zero of the first stage gives me a sense of relief as much as anything else.

My first Tour started with a prologue, and I will always remember the five-second countdown before launching myself down the ramp. I’d finally started the race of my dreams, and as I settled into the aero bars, I looked down to see huge goose-bumps covering my forearms. It was a magical feeling. I didn’t set the world on fire that day, but I didn’t care, I was a part of the big circus and I had a job to do for our team captains over the next 20 stages.

Some home truths dawned on me the following day during the first road stage. Looking around the peloton, I was amazed to see how lean some of the riders were looking. I’d raced with most of them over the previous months, and the extra ‘sharpness’ — the hollow cheeks and wafer-thin skin — still came as a surprise.

It made me self-conscious. I’d lost a kilo-and-a-half over the previous month, but that wasn’t enough to change my appearance. I was also aware that almost everybody around me was a known ‘name’; I couldn’t find anybody I’d have described as making up the numbers. Some of the domestiques are of high enough quality to be bona fide champions at the Classics.

Crème de la crème

The Tour de France bunch is the cream of the crop, and the cream of the crop at the peak of their form and motivation. I soon found out the effect that had on the speed and nervousness of the race. The first week was like nothing I’d ever experienced, the sheer strength in depth giving an extra couple of clicks to the speed. Coming towards the finishes and crunch points, the gaps between the riders were tiny. Nobody gives an inch in other races. In the Tour, nobody gives a millimetre. Physical contact with elbows and spokes touching rear mechs was far more common than at other races. It’s no wonder there are so many crashes in the first week of the Tour — there’s a lot at stake and many different agendas.

The last week of my first Tour was one of the most mentally and physically challenging times of my career. By that point, a lot of teams have got nothing out of the race: no stage wins, no time in yellow, green or polka dot. The managers and sponsors start to panic, and the fight to get into breakaways (which, by this point, stand a much greater chance of staying away) becomes manic.

Twice in the last week, it took more than 100 kilometres for the breakaway to forge clear. That isn’t 100 kilometres of stop-start racing, that’s 100 kilometres of constant attacks, chasing of attacks by teams who’ve missed it, counter-attacks and general carnage.

Another good example of this was stage 16 of the 2011 Tour, Hushovd’s second stage win, in Gap. The live television coverage started at 65 kilometres to go (out of 163), and the break still hadn’t gone. Average speed that day: 46kph.

In the end, I got through the last week, although I did spend a lot of time in the gruppetto. The nuances within the gruppetto are numerous; some riders like to set the pace at the front, some are happy to sit at the back. There are always people on good or bad days, and we generally help each other through.

It’s always interesting when someone is there who shouldn’t be, a GC rider who has got ill, for example. They don’t know the drill. Despite being off-colour, they still end up riding at a pace slightly too hard for the ‘regulars’, cue lots of abuse up the mountains. Then they get a big surprise on the descents.

The gruppetto descents are something rarely seen on television, but I’m almost certain they are the fastest of the entire day. The gruppetto is made up largely of heavier riders, sprinters with supreme bike-handling skills, and the descents are an opportunity to make up time on the front riders, aiding the chances of finishing within the time cut. On one mountainous stage of my first Tour, a GC rider (previously top 10 at the Tour) found himself at the back with the rest of us. The gruppetto formed on the penultimate mountain and said rider rode 1kph faster than was comfortable for the rest of us the whole way up, and then drifted back through the group at the top as he put his gilet on. I didn’t see him again until three kilometres to go to the summit finish — he’d been frantically trying to get back on, having been dropped by two minutes on the descent. He knew better than to push the pace in that last stretch.

An intimate arrangement

Rooming arrangements at the Tour are like most other races — we get a room-mate, and stick with them throughout the three weeks. At the Tour, the teams are nine riders, so there is always one person, at least at the start of the race, on their own. It’s often the team leader, or if they don’t like being alone, it’s the person who snores the most or has the strangest sleep pattern (night owls or early risers). I’ve always got on really well with my room-mates from the Grand Tours. We share everything, the highs and the lows; we get each other through and keep the morale high when it’s ebbing. Of course, as with any relationship, when we’re living on top of each other to that degree, there are things that start to piss us off, but there are rarely arguments. It’s a strange experience if a room-mate is forced to abandon the race. That night, they are still there, depressed and inconsolable, the following day they are gone, and it feels like I’ve lost a part of myself.

Finishing that first Tour on the Champs is one of my fondest memories. Every Grand Tour should finish in the same place every year, in my opinion – it gives the race a sense of identity, an iconic ending, and something for the riders and fans to look forward to year on year.

I’d only ever watched the Paris stage on TV, and it felt quite surreal as we entered the circuit. The leader’s team is always allowed to enter the circuit leading the race as a unit, but with a sprinter on my team, it was only a couple of laps before a break had formed and I found myself setting a tempo at the front of the bunch. The crowd was so loud it was incredible, drowning out every little noise that you normally hear within the peloton, I book-ended that race with goose-bumps.

The after-party, or stage 22 as it’s sometimes known, varies enormously in duration, excessiveness and cheeriness. If we’ve had a bad Tour, there isn’t much to celebrate apart from completing the course, but if a rider has won a jersey or the team has won the team competition, there is no excuse not to party.

Most riders will find any excuse to have a drink by that point. We are tired and exhausted, but the majority of us make one last push on stage 22, which is often the biggest endurance test of the race. We might head early to bed most nights, but when we party, I’d say we do a pretty good job. Some riders/staff will head back to the hotel sooner rather than later, but there are always a hard core who remain committed until dawn.

The comedown after the Tour is another thing it’s hard to deal with. I imagine it must be akin to a band having played to their biggest ever audience, a sense of, what next? One day I’m racing the Tour in front of thousands of fans, hounded by autograph-hunters, journalists, and among a group of 30 riders and staff, and the next I’m back home in my quiet town. After that first Tour, I felt lost, and the cumulative fatigue of three weeks finally kicked in with a vengeance, my mind finally relaxing and my body following suit. I hadn’t thought about what was next, and hadn’t made any more goals for the season. I didn’t touch my bike for a week, and I didn’t get back to top form, mentally and physically, until the start of the following season.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

-

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-Liège

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-LiègeUno-X Mobility to rebrand as 7-Eleven for Sunday's Monument to pay tribute to iconic American team from the 1980s

By Tom Thewlis

-

Rapha launches the Super-League, a new British road racing points competition

Rapha launches the Super-League, a new British road racing points competition16 events make up the Rapha Super-League, including crits and road races, with overall winners crowned

By Adam Becket

-

'Five or six WorldTour teams asked for my data' - Interest grows around world record breaker without a road team

'Five or six WorldTour teams asked for my data' - Interest grows around world record breaker without a road teamJosh Charlton says there's "definitely interest" in his signature

By Tom Davidson

-

Men's WorldTour 2025: Everything you need to know about the teams

Men's WorldTour 2025: Everything you need to know about the teamsThe leaders, transfers and team ambitions set to shape the season ahead

By Adam Becket

-

'It's a bit scary' - WorldTour's youngest rider to pair schoolwork with racing

'It's a bit scary' - WorldTour's youngest rider to pair schoolwork with racingA-level student Carys Lloyd is one of Movistar's latest recruits

By Tom Davidson

-

'We call it shadow' - MAAP brings grey bib shorts to the WorldTour with Jayco AlUla

'We call it shadow' - MAAP brings grey bib shorts to the WorldTour with Jayco AlUlaAustralian brand vows to add 'fashion influence' to sport's top level, and says grey colour is 'not as contentious' as AG2R's classic brown

By Tom Davidson

-

Global backers in talks over new British WorldTour team

Global backers in talks over new British WorldTour teamFormer management of Ribble Weldtite courting interest in new project

By Tom Thewlis

-

‘Current WorldTour system is killing all the smaller teams,’ says Reinardt Janse van Rensburg

‘Current WorldTour system is killing all the smaller teams,’ says Reinardt Janse van RensburgSouth African ex-Lotto Soudal rider fears more teams could find themselves in B & B Hotels-KTM situation if the system doesn’t change

By Tom Thewlis

-

As Cristiano Ronaldo puts the boot in, Jumbo-Visma talk to Manchester United about tactics and managing egos

As Cristiano Ronaldo puts the boot in, Jumbo-Visma talk to Manchester United about tactics and managing egosThe Dutch team’s senior sports director has spoken to Manchester United’s manager for sporting advice

By Owen Rogers

-

'It's a really absurd way of racing' - EF boss Jonathan Vaughters on WorldTour relegation scrap

'It's a really absurd way of racing' - EF boss Jonathan Vaughters on WorldTour relegation scrapEF Education-EasyPost manager says he hated racing for UCI points

By Tom Davidson