Inside bike design: From open moulds to owning the process

How many bike brands own the whole process, from start to finish?

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Bikes have become pretty expensive as of late. There are loads of reasons for that, not least the rising cost of manufacturing as China and Taiwan become the experts in a field where once they were considered the providers of cheap labour.

If the price tags attached to mainstream brands are too high, consumers will look to cheaper alternatives - one of which is buying an open mould model straight from the internet.

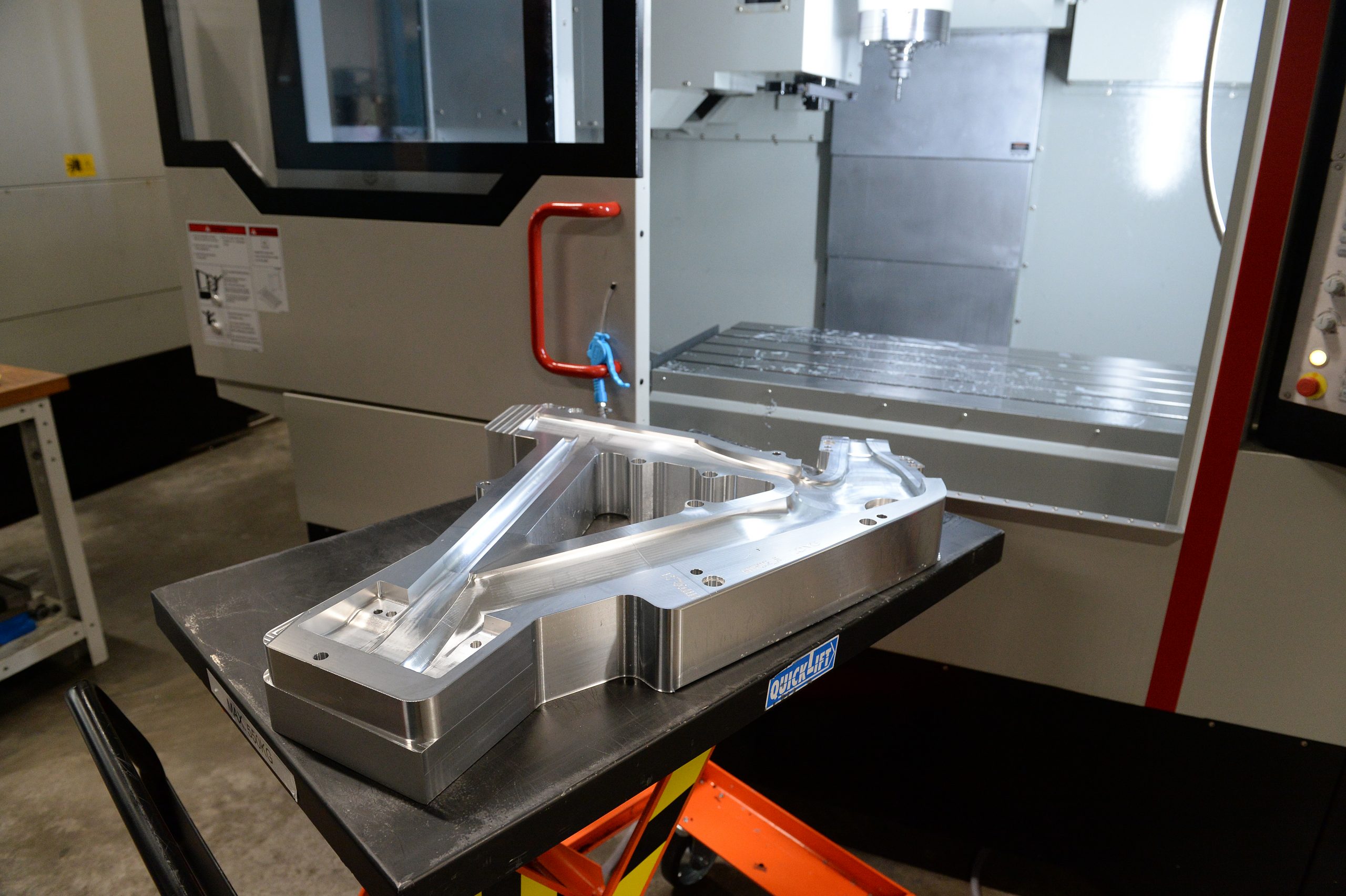

Let’s briefly take a step back before we go forward. Carbon bicycles are made in a mould. A very select few brands own the engineering capacity and resources to produce their own moulds. Factor and Giant are examples of brands who own their own factories, giving them the greatest level of control.

Many brands will design a frame, and pass it to a third-party manufacturer (Ten Tech, Giant, Topkey are all examples), who will develop an exclusive mould for them. This is a costly process, coming to around $100,000 for a complete set of sizes - of course the price will vary depending on exact requirements.

Alternatively, brands that are poorer still can go to Asia and select a factory that already has an open mould design available. The factory itself has paid for and owns the moulds, the brand orders a number of frames and supplies graphics to be added. Factories who offer this service are more likely to attend trade shows where they'll show off their wares, making the frames somewhat recognisable.

As per all catalogue purchases, the quality will vary massively. Sources tell us an entry-level frame and fork weighing around 1.5kg might come in from $200 if a brand were to purchase 100, but some open mould frames can be pretty high end, we've tested several among the Cycling Weekly tech team which have impressed us. Some are available for consumers to buy direct, online.

Asked how common each approach was, Factor CEO and former third-party contract manufacturer Rob Gitelis said: “Pretty much every bike brand being used at the Tour de France, be it a Pro Conti or a WorldTour team, is doing some level of research and development (R&D) and has their own moulds. Then there are the premium brands that aren't at the Tour de France, but have their own moulds, like Parlee, Argonaut. But then you have a load of other brands, using a third party or an open mould."

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In his former role, Gitelis and his factory created moulds for a plethora of household name brands, though he never dabbled in the "open mould side of things" he confirms. Now, the factory makes almost exclusively Factor Bikes.

“Every brand is different. But I would say that almost no brand [who uses a third-party manufacturer] knows how to make a frame. They have an understanding of the process. But whenever you see the brand saying ‘we made it 10% stiffer’, they mean 'we went to the factory and said we’d like to make this 10% stiffer’.”

That's not to say that all of these bikes will disappoint the customer, "those bikes will probably serve the purpose for the customer that buys them," Gitelis confirms.

Invest to innovate

Why don't more brands run the whole show?

“When we design a frame, somebody has spent tens of thousands of pounds on development. A significant amount of that goes on aerodynamics,” notes Dimitris Katsanis, the man best known for his work with Pinarello on the F8, F10 and F12, and the British Cycling's UKSI bike as well as the Hope track bike.

The brand may start with anywhere from 20 to 50 iterations being analysed by computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, before moving to wind tunnel testing using 3D printed structures, then checking such a structure for practical issues such as tyre clearances - and finally moving to real world testing beneath a pro-level rider who may provide further feedback.

“That’s quite a large amount of work that somebody has to pay for. Then you need to get some money out of it to start funding the next generation!” he says.

All of that is expensive but without it happening we'd be riding the bikes of “20 years ago" Katsanis notes, when "there were hardly any carbon bikes, they were mainly aluminium bikes with round tubes.”

Brands don't need to own their own factory or make their own moulds to create an aerodynamic frame, but they do need to have some serious resources to inform the design they take to the factory.

"CFD and wind tunnel testing is something the brand does ahead of confirming the shape with the factory before going ahead," Gitelis said. "I always find it funny when you see pictures of a complete bike in the wind tunnel. 'What are you going to do, change it now?' I want to ask. The brands need to do any CFD simulations or wind tunnel testing hopefully before going and opening moulds. That testing would belong to them."

Material costs

Interestingly, the two design experts gave me a different take on material costs. Likely because whilst Gitelis knows the mass-market industry inside out, Katsanis has a background in creating bikes to appear on the Olympic stage.

According to the latter, the distinction between the best frames and lower-end open mould options is the resin.

Carbon is purchased in varying levels - manufacturer Toray offers T700, T800 and so on - the higher numbers signify better quality that is lighter and stronger. Resin is mixed with hardener as part of the pre-preg process which turns raw carbon fibre into the material that goes into the mould. To the untrained online shopper, one T800 frame may appear equal to another.

“One common misunderstanding is that all T700 or all T800 is the same. Composites tend to be significantly stronger in tension when you’re pulling it and not as strong in compression when you push it together. Under tension, the dominant factor is the fibre itself, the resin makes little difference. In compression, the resin has a very significant difference. The compression strength can be doubled by using a better resin," explains Katsanis.

He says that cheaper factories use cheaper resin, adding: "When you ride a bike, the tubes flex all the time. A year down the line, the frame may feel 'mushy' as though the stiffness goes down. The reason for that is the cheap resins start cracking between the fibres - this is really why the stiffness on cheap frames goes down.

“I made the first bike for British Cycling in 2002, using a fibre and resin that is used in Formula 1 on the nose cone of the car - that's the bit that hits the wall in a crash. They’re still riding these bikes today because the quality of the material is significantly better than off the shelf.”

Katsanis says that the same square metre of carbon could range from £10 with an in-house resin, to £25-30 with a high-quality resin, reaching £200 with a top-quality carbon fibre and resin combination. A manufacturer could purchase an entry-level open mould carbon frame and fork from about $200 all in, if they bought approximately 100.

Comparatively, Gitelis' experience is that most of the manufacturers are using the same materials - resins included.

“Almost everyone - even open mould manufactures - are basically getting the carbon fibre that factories are supplying to you. Yes, there are lots of different resin systems. But ‘bicycle’ is in the sporting goods division of most carbon fibre suppliers, so they are giving you materials from the carbon fibre catalogue. When we were a contract manufacturer, we had the materials that we wanted to work with at our factory. We told our customers these were the four or five material choices that we’ll be working within - never once have I had a customer say they want to use a different resin.

“In mass production, you don't have that much flexibility the way you do when you’re making one or two of a frame for Team GB," he said.

Quality control

Both Katsanis and Gitelis acknowledge that imperfections happen. But both point to the fact that imperfections are reduced when the brand has more control and input.

"The bike industry, in general, is a little less mature than other industries, and compared to most our volumes are very small," Gitelis states.

“Fit and finish was something we wanted to take very seriously at Factor, and we own our factory so we have complete control. Some brands have their own quality control (QC) units located in the factory. Some companies rely solely on the factory to do the checking for them. And different factories have different standards.

“We all know there are products arriving at dealers that still require facing”, he says, referring to the process by which a mechanic would tap threads or removed material before fitting components.

“Things like that come down to money and it frustrated the heck out of me. To do all of those things perfectly would probably add $10-$15 to a frame. Yet a lot of brands are so cost-conscious that they don’t spend that money. The problem the industry has is that $10 becomes $100 by the time it reaches the consumer."

Batch testing is something that Gitelis says Factor is hot on within its factory.

"We test one in every 100 frames to destruction. That comes at a cost but it lets us know with every batch if there’s anything to be concerned with, and if that frame happens to fail we would stop the production line and review the other 99 frames. Some companies are doing that, and some don't.

"Those who test thoroughly will be those who have so much to lose: Specialized, Trek, Giant. They’re a safe bet. Canyon is always doing a very good job with its testing."

“If your own name is on that bike, you have to make sure that it’s good," Katsanis chimes in. "If you as a manufacturer are selling this bike to 10 different brands and they’re all sprayed in a different way, and they have different names on, no one will come back to you if they fail. Some intermediate may be unhappy but it doesn’t bother you. These factories don’t have the incentive to be very strict with QC. Their risk is minimal. If brand X gains a bad reputation and goes under, brand Y will approach you tomorrow."

Regarding the distinction between buying a frame from a brand that has used an open mould vs buying an open mould frame yourself, Gitelis points out that the former is much safer in terms of the warranty.

“Most likely if you buy a frame from an open mould brand vs buying a frame from an online retailer that uses open mould frames, you’re getting the same frame. One of the differences is that in the former case you’re dealing with a faceless transaction. So if something goes wrong you don’t have any sort of recourse if there’s any problems with it.”

Closely related is the issue of counterfeit frames, which directly mimic premium brands - even sometimes down to the logo.

“My biggest issue with direct-to-consumer open mould websites is that they’re one step away from counterfeits. Sometimes the websites contain counterfeits," Gitelis notes.

“We bought some of these products and tested them. Some are OK... some are actually dangerous. It's frustrating and time consuming for us trying to stop it. We pay companies to go through the websites. When they find these sites selling our products, they notify the website providers and get the shop shut down. The next day the shop has changed its name.”

Factory conditions

Carbon bike frames are labour intensive to produce, and one thing to consider when you’re buying a frame is the welfare of the workforce.

“In the good factories, as they rub the frames down they have systems in place to extract the air away from the person who is doing the job. In the cheaper factories, you go in there and the whole area is full of a semi-black cloud, from the dust of carbon. The people have no masks, no gloves, no nothing,” Katsanis says.

Interestingly Gitelis does not believe any ‘sweatshop’ conditions exist within Taiwan or China, but he notes that some brands are moving elsewhere as the market leaders hike their pieces; moves to cheaper areas are not exclusive to manufacturers producing cheaper bikes, he says.

“I can only speak for China and Taiwan. Here, for the most part, no one is being forced to do a job they don’t want to do in a factory they don’t want to work in. People have the idea that Taiwan is a big sweatshop, but it is far from it. In China, there are more jobs than people.

"[But] the industry has been moving to places like Myanmar which I have a very serious problem with. An employee in China is making maybe $1,500 per month. An employee in Myanmar is making $12 or something like that. The fact that our cycling industry is willing to go to those countries and participate in that exploitation, I don’t think it’s right.”

You probably don't "need" a World Tour bike

Both of our experts advised against purchasing open mould frames direct, the primary reason being a lack of accountability if things go wrong. The frames available from brands who have purchased open mould creations and badged them up? Probably will do the job, if a little less innovative.

The question is, is doing the job what you want?

"When I do a design for Pinarello, I’m designing for Carapaz or Bernal," says Katsanis. "And when you buy that bike you know that you’re buying the same bike that these guys are riding. You don't buy it because you want to be world champion, but because you want it. When you buy a Ferarri, you won't go to the supermarket any faster. Do you need it? No! You don't need a bike at all either, you can walk! In the vast majority of cases - the question is ‘do you want it?’."

And if you want it, but the cost is prohibitive? Gitelis points out that buying second hand brings with it many a benefit.

"If somebody wants to get a bike, but doesn't want to spend loads - check out things like the Pro's Closet. Bikes now are getting turned over very quickly - almost like iPhones, and they depreciate like cars.

"Buying a second-hand bike is not a bad idea, you get a very good quality bike, and it contributes to creating a circular economy."

"I bought open mould..."

Of course, representatives from high-end and mainstream brands are going to have a bias against open mould models. We asked cyclist Richard Hill to tell us about his experiences - he's bought "15-20" open mould frames over the past eight years, four for himself and the rest sold via his own shop Sugar Velo...

Originally I was looking for a new bike and had a budget which restricted me. I came across Chinese supplied frames on eBay and I liked the idea of getting a frame only and choosing the components myself.

I have been really satisfied with all the frames I have had. When I’ve had the opportunity to view the construction of more well-known brands, visually the open mould frames are very comparable. When building the bikes up, all the cable runs and threads work well, bottom brackets and headsets are nicely machined. Recently I’ve been using the option of having the frames custom painted directly from the supplier.

Bikes have to ride well too, and I’ve tried to put them through the paces. I’ve competed at club level TT on a lo-pro, ridden numerous national and European sportives along with multi-day tours on these bikes. My last venture was taking part in the AMR (Atlas mountain race) on a gravel version. The frames all inspire confidence. But they also have a great balance with comfort.

When I'm choosing a frame, I look at the geometry documents, the materials spec, weight and the compatibility to different systems, like Di2 and disc brakes.

If you're considering the open mould market, the most important thing is finding a reputable supplier. There will be a certain amount of trust involved when dealing with manufacturers abroad for the first time, and there is a need to build a relationship with that supplier before parting with money.

In the beginning, I had to weed out a number of enquiry returns as I wasn’t happy with the responses to my questions. I like to see a website and some description about the company. Watch out for the hidden costs. Paypal is the best method of payment and some pass the fees on, also shipping and duty and VAT will be added. Try and avoid ordering around Chinese new year as it normally adds 2-3 weeks of lead time. Warranty is normally a question asked, to date I’ve never needed to use it, but the manufacturers I use offer warranty for 2 years.

The manufacturer I chose supplied certificates of testing and QC, and I’ve seen images of the factory and working conditions.

Buying an open mould bike isn’t for everyone: it's certainly more hassle and work than buying from a major brand, and the support structure isn’t the same. You need to put in the work to make sure you choose a reputable supplier. But there are real savings to be made for a comparable model.

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her first daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

Michelle is on maternity leave from April 2025 until spring 2026.