The Hotta story: how monocoques and bullishness won Olympic gold in 2000

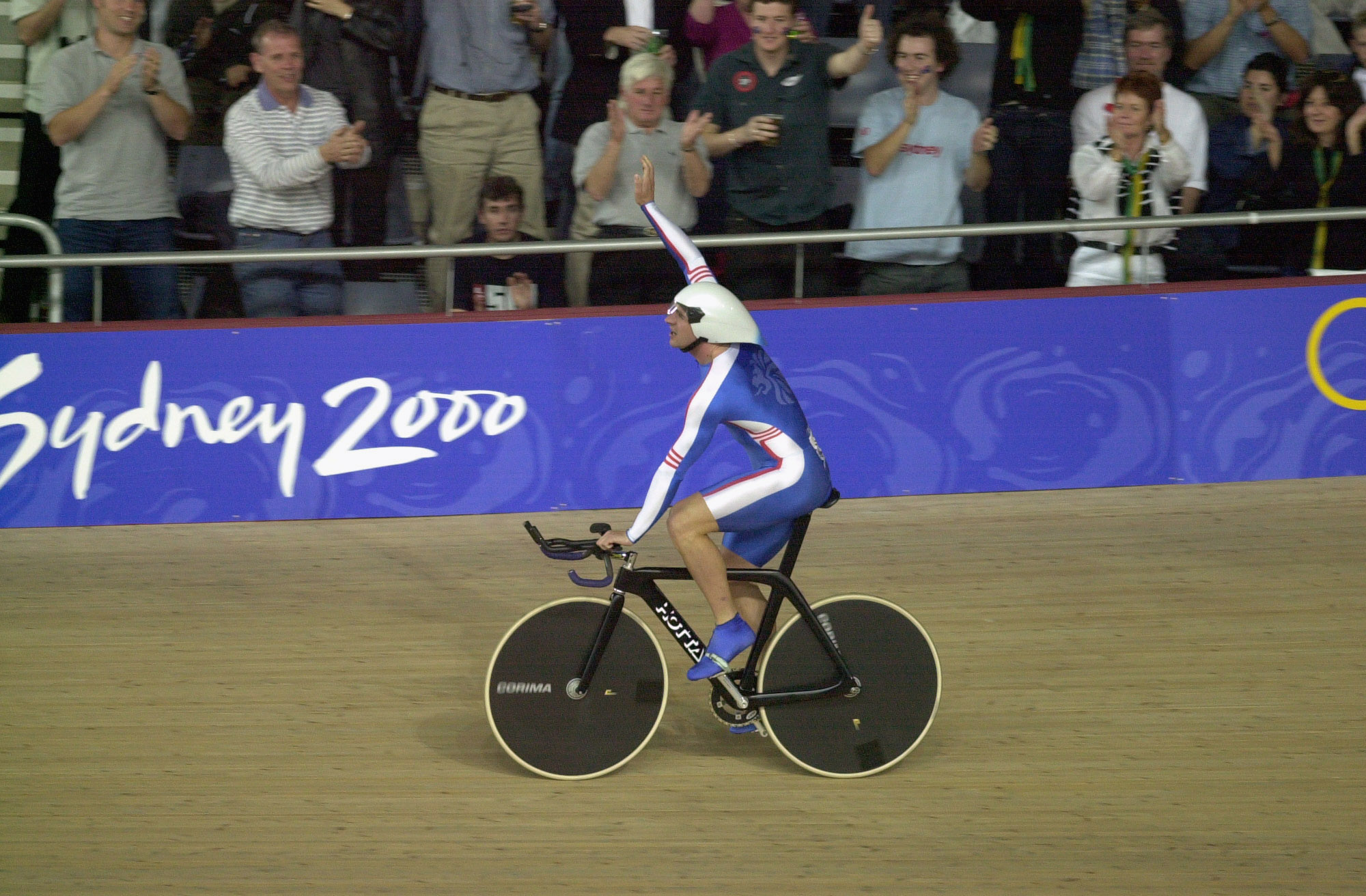

Lotus might have kickstarted the carbon monocoque revolution in 1992, but it was Devon-based Hotta that carried Chris Boardman to two Tour de France prologue victories in 1997 and 1998, finally winning Olympic gold in Sydney with Jason Queally. CW talks to Hotta founder Simon Aske for the story of 'the other 1990s British superbike'

In the days before Britain was good at cycling, the mainstream media used to try to find an interesting angle for its rare successes, usually focusing on the bike rather than the rider. If it wasn’t a bike made by a F1 constructor or sports car manufacturer then it would have to be one made from a washing machine. In the case of Jason Queally’s gold medal-winning ride in the kilometre time trial at Sydney 2000, it was a bike made in a garage. According to the Daily Telegraph, Queally’s Hotta racing bicycle was made by one man, Chris Field, a "freelance designer from the village of Galmpton in Devon, who had to clear his garage to make space for the project."

However, the mainstream media either didn't know or glossed over the fact that it was not a humble beginnings but a humble endings backstory: this was Hotta’s last hurrah, and Field was anything but a plucky amateur, despite the Telegraph quoting him as saying: "We've won the gold with a bike put together, bulldog style, in a garage."

The company had built bikes for the greatest British riders of their generation and sold forks to the Motorola and Festina pro teams but was now being wound up. The Hotta factory in Totnes had closed and the remains of the company had moved to Norfolk, which was why Queally’s gold medal-winning Hotta Perimeter – and the four Perimeters that were ridden to the bronze medal in the team pursuit – were built in Field’s garage.

Overnight success

Eight years earlier, Hotta’s original success happened very quickly. Although the designer of the original Hotta monocoque, Simon Aske, developed his bike independently of Mike Burrows and Lotus – he even thought they must have copied him somehow – Chris Boardman’s 1992 Olympic gold on the Lotus bike catapulted the carbon monocoque to the top of everybody's wish list.

>>> For the love of Lotus: the story of the iconic Lotus 110

In 1992 Aske, a mechanical and production engineer, was working for a company called Carbon Infinity and was making lightweight carbon-fibre bodies for medium format cameras.

“I was cycling to work on a dog of a bike and I thought, you know what, I’ll make a carbon one. So I drew a saddle, some wheels and handlebars and worked out how to join the points together.

“Pete Goss, who designed the Goss Boat, was one of my bosses. He and a guy called Barry Noble worked out the best way to mould the monocoque in two pieces.”

Aske’s original design used a single stay at the rear, like the Lotus pursuit bike.

“We made a wooden buck and took the moulds off that. There was no CFD, no wind tunnel, we were just looking down the lines of it and that’s how it was done.”

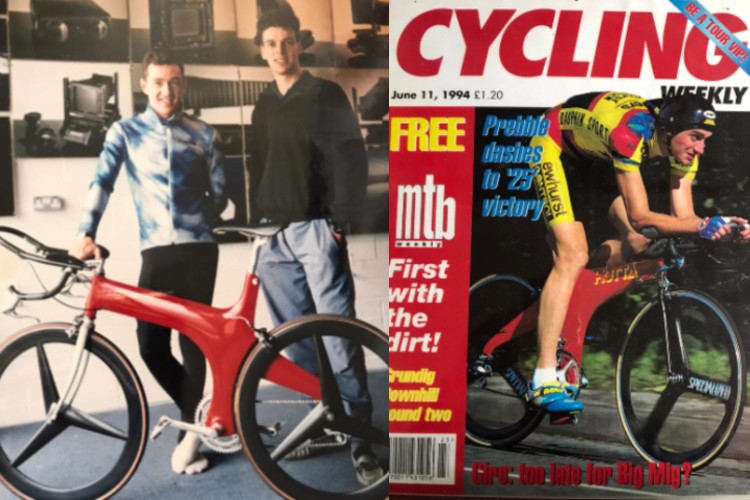

Soon after the 1992 Olympics, Chris Boardman visited Carbon Infinity and tried out Aske’s design. “He was thinking about using it for 1993 with his Kodak-sponsored North Wirral Velo team. We had also started making a Carbon Infinity wheel, which was a tri-spoke, and he was thinking about using those. It didn’t really work out because we didn’t have the tools to support him as much as anything. But he showed me his gold medal.”

Carbon Infinity and beyond

“Carbon Infinity was going through some difficult times so I thought I’d set up on my own," says Aske. "I had worked previously with a guy called Chris Field. We were making sports cars, basically: like a Lotus Seven but with a Rover V8 lump in it. That company went bust, which is why I ended up at Carbon Infinity. So I went to Chris and said, what I want to do now is make it [the Hotta monocoque] commercially available. So that meant putting two rear stays on it. I said I wanted it to look a little bit better, and he was a car stylist, so he did all the styling.

"Steve Nichols, who looked after Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost at McLaren, was funding it. So that’s how Hotta started. We produced the first one commercially towards the end of 1993.

“So then we placed adverts in Cycling Weekly, we rang British Cycling and looked for a rider to ride it. Doug Dailey was there at the time and he put us in touch with Richard Prebble. His first ride on the Hotta was the National 25, which he won and it got the front cover of Cycling Weekly. It went on and on.”

Cycling Weekly's Richard Hallett reviewed the Hotta in 1995. At the time the cost was £975 for the frame only, which weighed 2.9lb (1.3kg). Hallett wasn't keen on "the rumblings that accompany any forward progress, having to let the the tyre down to get the back wheel out and the lack of provision of a frame pump," but otherwise wrote it was "a fantastic bike ... it has all the looks, feel and lack of weight you could want."

Prebble went on to win the National 10, 25 and 50 in 1995, and around that time Hotta started working with both Boardman and Obree.

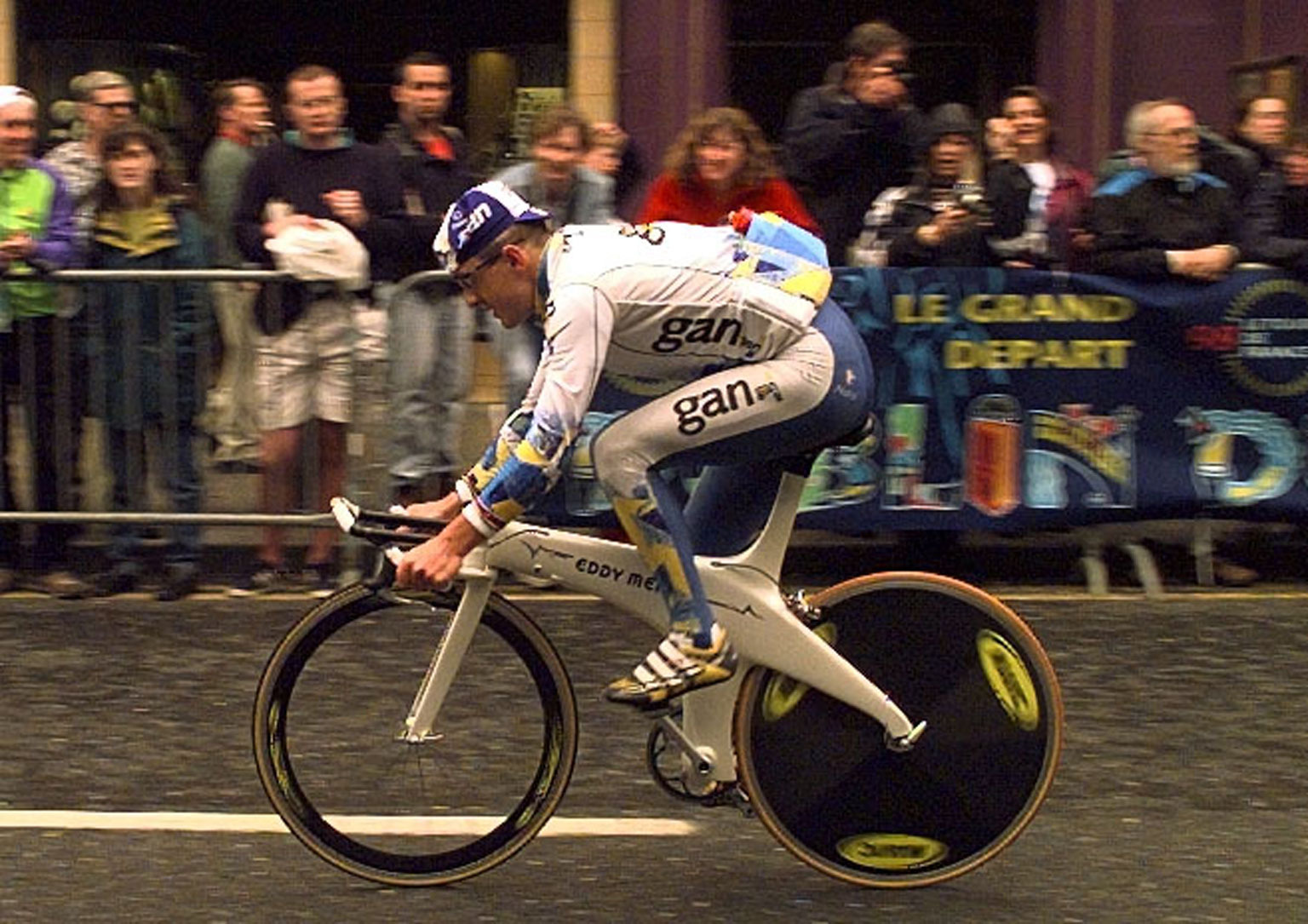

“Boardman had spotted a carbon fork on someone’s bike at Manchester velodrome so asked us to make a pair. He used them to win the time trial stage in Paris-Nice in 1996,” says Aske.

“In the Tour de France that year Lance Armstrong and Motorola and also Festina were on our forks on their TT bikes,” says Aske. “They were light and I don’t think many people apart from Colnago and Look were making carbon forks. They were certainly the first aero carbon fork out there.”

Boardman used a Hotta fork, made to his own design with the base bar emerging from the sides of blades so that he could achieve his super low position, for the Olympic time trial in Atlanta, winning bronze.

Additionally, Hotta had built a very special bike – or rather three bikes – for Graeme Obree to ride in Atlanta in the 1996 Olympic pursuit and in the road time trial. There was a lot at stake. Great Britain was the reigning Olympic champion in the individual pursuit after Boardman's Barcelona gold in 1992 on the Lotus. The bikes – only three of the four were made in the end – cost “a dreadful amount of money” according to Aske, reportedly £125,000. It might have been money well spent, had Obree used the bikes.

“He won the British national pursuit on the Hotta that year, but then at Atlanta he went back to Old Faithful. I don’t think Chris [Field] was very happy about it. He didn’t do very well and he wasn’t on our bike so it wasn’t a bad report for us, but it’s not until you read his book that you find out about the difficulties he was going through at that time.”

Additionally, Hotta had put a carbon skin on Obree’s second ‘Old Faithful’ for his second hour record in 1994.

And Boardman used the Hotta fork adapted for the superman position with his Lotus 110 for his ‘ultimate’ hour record in September 1996, which remains unbeaten.

“We were working with the two best riders in the country,” says Aske proudly. Hotta would also go on to also supply the two best teams in the country – Vic Haines's Team Clean, which he built around Sean Yates, and the Linda McCartney team. Paul McCartney was even photographed astride a Hotta for a publicity shoot. Hotta had literally become the Beatles of bike racing.

But 1996 was Aske’s final year with Hotta. "We lost a lot of money with the Obree thing [Atlanta] and I had to go," he says with a rueful laugh.

Aske wasn’t involved any more when Boardman won the Tour de France prologue on a Hotta in both 1997 and 1998, and wasn’t part of the development of the Perimeter, Hotta’s ‘traditional’ diamond-framed bike that was designed in response to the UCI’s Lugano charter banning monocoques from 2000.

“There had been changes – Steve Nichols had pulled out at the end of 1995 and the company was bought by two South African guys who were from the Norfolk area.”

Aske isn’t willing to go into detail about Hotta’s final years – and says he doesn’t know the details anyway.

Cycling Weekly tried to contact Field without success, and Aske was unable to put us in touch. “I haven’t seen him for a while,” he says, “and I can’t see his number in my contacts."

Hotta for the 21st century

Aske now owns Colin Lewis Cycles in Paignton and has his own bike brand, building custom steel frames. However, he says he now owns the Hotta name again. So could we see a 21st-century Hotta?

Although Aske no longer has the moulds and doesn't know where they ended up, he says: “It’s in the back of my mind to make some new ones. You'd need to modernise them anyway, because technology has changed a lot in the last 25 years. I think it’s time to do a non-UCI bike because design has completely stagnated. Bikes all look the same now.

“There’s a lovely little company in Newton Abbot that I did have some discussions with about doing it. It’s not something I really want to do myself because of the chemicals and the dust – horrible – and I’m not a youngster any more, but I would certainly work on the design. They might be struggling a bit themselves now, but they were making some really nice stuff for McLaren cars. Parts were coming out of the mould and you didn’t need to do anything to it – no pockmarks, nothing. But you’re looking at a lot of money to make moulds. If you were 3D printing that might bring the price down, and it’s easier to do now. It was very time consuming making a buck and then a mould.”

Aske still owns a Hotta. “They still look absolutely fantastic today," he enthuses. "That design hasn’t aged. I rode mine two or three years ago in a 10 mile time trial. I’ve still got the carbon Hotta Pro fork in. I even road raced on mine back in the day.”

In recent years the Hotta monocoque – called TT700 or TT650 in the version for smaller wheels – has achieved cult status in UK time trialling and is now a highly sought-after classic bike.

But the question remains: Lotus or Hotta? “The Hotta is a better bike than the Lotus," says Aske. "It definitely is. And it’s a lot lighter.”

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Simon Smythe is a hugely experienced cycling tech writer, who has been writing for Cycling Weekly since 2003. Until recently he was our senior tech writer. In his cycling career Simon has mostly focused on time trialling with a national medal, a few open wins and his club's 30-mile record in his palmares. These days he spends most of his time testing road bikes, or on a tandem doing the school run with his younger son.

-

Deuter's 30ltr commuter backpack

Deuter's 30ltr commuter backpackA rolltop bag to fit a change of clothes and a sandwich. And keep them dry

By Simon Richardson Published

-

The thing that bothers me most when I look back at old school training is that right now we’re doing something equivalently misguided

The thing that bothers me most when I look back at old school training is that right now we’re doing something equivalently misguidedOur columnist's old training diaries reveal old-school levels of lunacy

By Michael Hutchinson Published