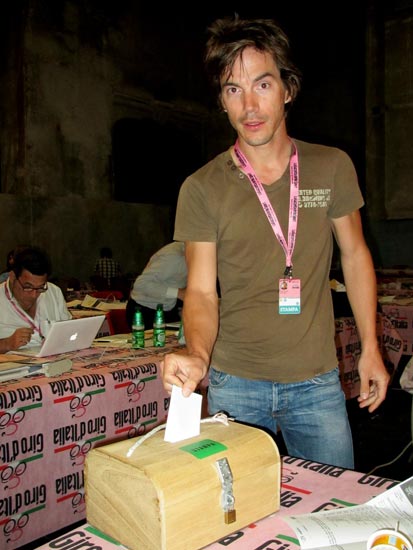

Danilo Di Luca: 'If I had never doped, I wouldn't have won'

Italian Danilo Di Luca talks about doping during his professional career in his new book, published this month

Banned Italian cyclist Danilo Di Luca has released a book, Bestie da Vittoria, this month on the story of his career and his doping. In the book, he says that he had to dope, otherwise he would not have won.

Di Luca received a lifetime ban in December 2013 after failing his third anti-doping control in a career that included the 2007 Giro d'Italia and wins in all three Ardennes Classics.

"I could not have not doped," Di Luca said in an excerpt from the publisher. "Doping improves your performance between 5 and 7 per cent, and maybe 10 to 12 per cent when you are in a peak shape. If I had never doped, I wouldn't have ever won."

Di Luca last raced the 2013 Giro d’Italia, where a control showed he used EPO.

>>> Danilo Di Luca banned for life (2013)

"Doping is not addictive, but it is an instrument of power: who wins brings in the money. To himself, to the team and the sponsors," Di Luca said in an excerpt published by Tutto Bici.

He said he started taking drugs in his fourth year as a professional, in 2001, after seeing the riders he used to beat as an amateur ride away to victories.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"Testosterone, EPO, cortisone. The doctor cannot get the prescription so then you acquire them on your own, in gyms or on the internet. Environments everyone knows," he said.

"It's part of the job. If you get caught, then you timed it wrong because everyone knows how many hours must pass before you won't show a positive. "

>>> ‘We need evolution, not revolution, in anti-doping’

Di Luca tested positive for blood booster EPO on April 29, 2013, in a pre-Giro control. The announcement of the result came on May 24, when the Giro sat still due to a snow.

It was the third time in a colourful career. When he won the 2007 edition, he returned suspicious urine tests along the way, but escaped consequences. The 2004 Oil for Drugs investigation showed he used EPO, however, and he served a three-month ban. He was caught using EPO again after the 2009 Giro, where he had won two stages.

Watch: Cycling Weekly anti-doping debate highlights

In 2013, he prepared for the Giro in the same way. "It included doping and non-doping substances: vitamins, amino acids, supplements, protein, EPO, cortisone, hormones of various types, corticosteroids, testosterone," he explained in a longer excerpt from the publisher.

On April 28, at 23:00, he injected 500 units of EPO. "Fifteen years ago, before the hematocrit controls, some would do up to 4000 units per day. Madness. I knew that 500 units would stay with me for three to six hours. Even if they came in the morning, I'd show clean."

Testers knocked on his door in Pescara the next morning at 6:00. Di Luca, known as 'The Killer' in Italian cycling, had not heard about a new detection method that could spot EPO in blood for up to 24 hours. "My calculations were worthless."

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Gregor Brown is an experienced cycling journalist, based in Florence, Italy. He has covered races all over the world for over a decade - following the Giro, Tour de France, and every major race since 2006. His love of cycling began with freestyle and BMX, before the 1998 Tour de France led him to a deep appreciation of the road racing season.

-

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much more

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much moreSupported It's not just Bontrager, Balfe's has a huge selection of discounted kit from the best cycling brands including Trek, Specialized, Giant and Castelli all with big reductions

By Paul Brett

-

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-Liège

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-LiègeUno-X Mobility to rebrand as 7-Eleven for Sunday's Monument to pay tribute to iconic American team from the 1980s

By Tom Thewlis