Forging legends: Here are the 10 best Classics of all-time

Do you agree?

Johan Musseuw at Paris-Roubaix 1996 (Pascal Rondeau/ALLSPORT/Getty)

All winter we waited for the spring Classics. All winter. Milan - San Remo, the Tour of Flanders, Paris-Roubaix, Liège.

But now they're gone. The world currently has more important problems, obviously, and massive bike races with riders from all over the globe aren't conducive to beating a virus.

Therefore, the only thing we have to occupy our time with is reminiscing on editions gone by. That's pretty much all there's left to do, right? Merckx, Museeuw, Boonen. The Good Old Days™. That is all that's left. Cherish those dreams of a wet Paris-Roubaix, hold onto the idea of a boring opening 150km of Milan - San Remo, hold it close.

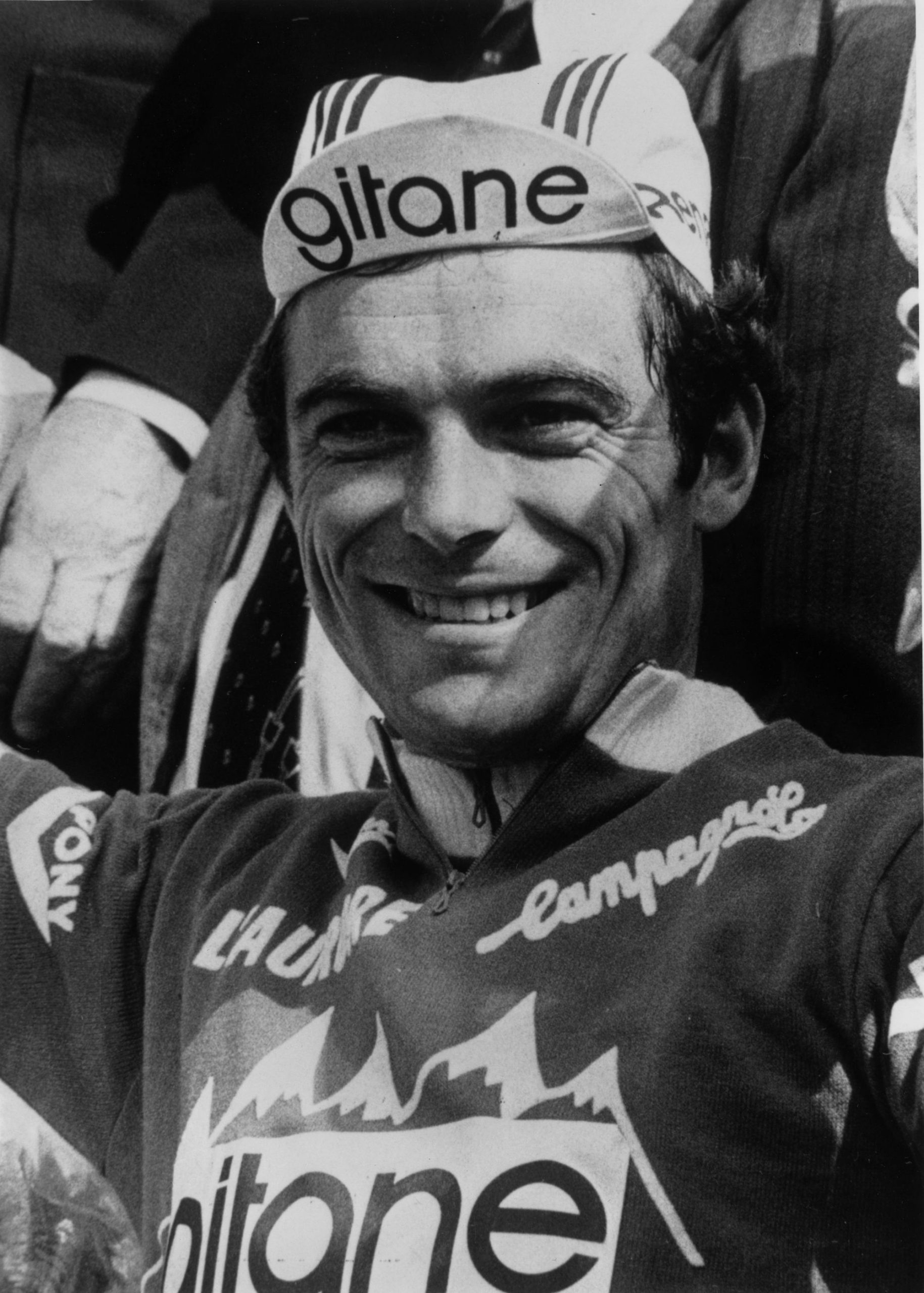

1. Liège-Bastogne-Liège 1980

Like the 1988 Giro d’Italia stage in a snowstorm over the Gavia that resulted in Andy Hampsten taking the maglia rosa, the 1980 edition of La Doyenne produced an unforgettable day of racing, iconic images and a heap of astonishing tales. On a day of bitter cold and snowy squalls, Bernard Hinault finished more than nine minutes ahead of runner-up Hennie Kuiper, as only 21 riders completed the long loop back to Liège through the Ardennes hills and forests.

It was snowing when the 174 starters got underway. Riders began to abandon as the peloton headed up the ridge to the south of Liège, Lucien Van Impe climbing into a car that he presciently told his wife Rita to park on the edge of the city. Others took refuge in cafes and restaurants as the snow began to fall more heavily. At Bastogne, there were only five dozen riders still on the road.

Hinault acknowledged that he too thought about quitting, but was encouraged to keep riding by his team-mate and close friend Maurice Le Guilloux, their Renault team director Cyrille Guimard, and the appearance of the sun. During another snow flurry on the Côte de Saint Roch climb, Hinault told Le Guilloux that he would quit at the feed station just before the Côte de Wanne if it was still snowing, but the sun reappeared and he pressed on.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Riding towards the Côte de Wanne, Guimard drove up alongside his team leader and told him: "Take off your jacket. The race is starting now." Hinault assumed he was joking, but Guimard insisted and off it came. Hinault now had no choice but to ride faster to keep warm. He surged up the Côte de Stockeu, dropping the small group he’d been in, closing the gap on lone leader Rudy Pevenage. On the next climb, the long drag of the Haute Levée, he reeled in Henk Lubberding, Ludo Peeter and Silvano Contini and led them across to Pevenage.

Hinault went to the front, setting a pace intended to pull this group away from any chasers behind. After a few hundred metres he glanced back to see why no one was helping him with the pace-making to find he was on his own. There were still 80km to the finish.

He pressed on, encouraged by the perseverance of the fans still at the roadside. On the final straight in Liège, riders who had abandoned earlier in the day turned out to cheer the Frenchman, who crossed the line without any victory celebration. "I didn’t raise my arms because I was completely done. If I had raised them, I would have fallen flat on my face," he later explained. His team-mates had a hot bath waiting for him. But Hinault insisted they empty it and fill it with cold water so that he could start the process of thawing out. Forty years on, he still feels the effects of that day, some of his fingers going numb when the temperature drops towards freezing.

"I suffered but not physically. My legs were in good shape. When you are in form, you can deal with anything," he later recalled. "I was on a great day, so the victory was logical, although perhaps not easy. I wasn’t so much fighting against my rivals as against the cold…"

Peter Cossins is the author of The Monuments: The Grit and the Glory of Cycling’s Greatest One-Day Races (Bloomsbury)

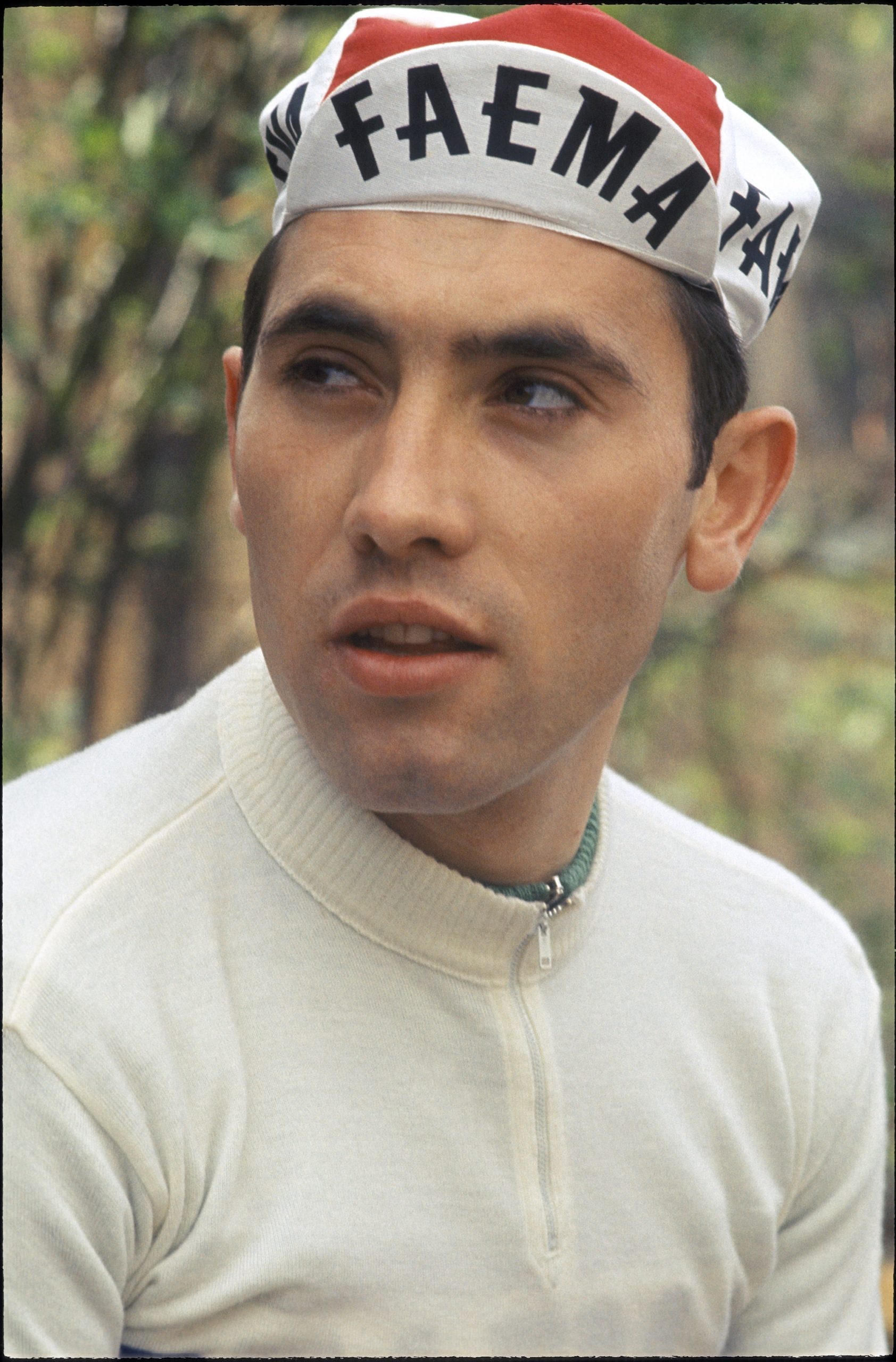

2. Tour of Flanders 1969

It may be hard to imagine now, but Eddy Merckx went to the 1969 edition of the Ronde with the Belgian press questioning his ability, Het Nieuwsblad suggesting in its race preview that the Belgian lacked the necessary qualities to win a race as tough as Flanders. The doubts stemmed from pro-Flemish bias against a rider from cosmopolitan Brussels, but only served to fire up Merckx, who had been bitterly disappointed at missing out in Flanders in the previous two seasons.

The Belgian wanted a hard race, one where the weather conditions were tough, and race day arrived with a vicious wind blowing in off the North Sea. Figuring his rivals would want to save themselves for the race’s finale, Merckx instructed his Molteni team-mates to set a fast pace to the key climb of the Kwaremont, just beyond the halfway point. Here and on the subsequent ascent of the Kruisberg, ‘The Cannibal’ took over the pace-making himself, reducing the front group to just 11 riders. He persisted with his infernal pace on the Muur and the Valkenberg, going clear on the latter with 70 kilometres remaining to the finish. His directeur sportif, Lomme Driessens, drove up alongside him and told him to ease off. Merckx refused.

>>> Subscriptions deals for Cycling Weekly magazine

The wind was strong enough to blow apart any concerted attempt to chase behind Merckx. Eventually, Felice Gimondi took up the pursuit on his own, opening up a gap of more than two minutes, yet the Italian still rolled in more than five and a half minutes behind Merckx. This proved to be a foresight of the performance Merckx would serve up in his Tour de France debut three months later, when he took the title with an advantage of more than 17 minutes.

3. Milan - San Remo 1992

The race had been billed as the coronation of Moreno Argentin, the Italian who had already won four editions of Liège, as well as Flanders and the Tour of Lombardy, but had never finished on the podium in San Remo. Leading a powerful Ariostea team guided by the legendary Giancarlo Ferretti, one of the most successful team directeurs in racing history, Argentin bided his time, waiting to make his move on the Poggio.

Come San Remo’s final test, Argentin was straight out of the blocks, attacking no less than five times, shredding the front group. "He seemed to be moving as easily as the motorbikes in front of him such was the rage he was putting through the pedals," reported La Gazzetta dello Sport. He crested the Poggio with a lead of seven seconds over Maurizio Fondriest and his own Ariostea team-mate Rolf Sorensen. A little further behind this pair was Sean Kelly, the 35-year-old Irishman’s Classics-winning days apparently behind him. On the short, but very technical plunge from the Poggio to the edge of San Remo, Kelly delivered a masterclass in the art of descending, every bit as daring and controlled as we’re used to seeing from Vincenzo Nibali and Julian Alaphilippe in the modern era. He breezed past Fondriest and Sorensen and started to eat up the deficit to Argentin, who was starting to think that the title would finally be his.

The footage reveals a look of disbelief on the Italian’s face as Kelly surges up to him with a kilometre still to the line. Argentin is quick in a sprint from a small group, but he’s no match for Kelly, a specialist. The result is a foregone conclusion, the Irishman celebrating what will be the final Classics victory of his long career, Argentin, meanwhile, despondent, his best chance of winning San Remo denied by a show of brilliance that neither he nor Ariostea had foreseen or could control.

4. Paris-Roubaix 1994

The perennial desire among fans for a wet Roubaix is fed by memories and legends of past editions where the sheer awfulness of the weather has contributed to a race for the ages. Think of Bernard Hinault’s glorious win in the mud in 1981, or of Andrei Tchmil’s defiance of the snow and rival Johan Museeuw in 1994.

It was an era when the use of suspension forks had become popular in the peloton, with Tchmil (pictured) and Museeuw among those emulating 1993 champion Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle by employing them. After several days of snow, the race got underway in cold conditions, occasional flurries still gusting through, leaving the pavé wet and muddy.

Tchmil attacked 67km from the finish in Roubaix’s velodrome, Museeuw leading the pursuit behind the Lotto rider. Their duel ebbed and flowed over the next 40km, the Belgian closing on his Moldovan rival, who would then extend his advantage a little, always strong enough to maintain his advantage. When Museeuw’s rear suspension failed late on, Tchmil sailed on to claim an epic victory in a race that veteran L’Équipe journalist Pierre Chany described as being the toughest he’d seen in the post-war era.

5. Milan - San Remo 1946

There is arguably no other race that has had as much symbolic significance as the first post-war edition of La Primavera. With Italy still devastated by the ravages of the Second World War, Fausto Coppi delivered a performance that not only enthused millions listening in on the radio, but provided a sense of optimism, a feeling that better times were coming.

Coppi had trained brutally hard to achieve his objective of winning San Remo, but arrived at the race unsure of his tactics. Noticing that several track specialists had registered to race with a view to capturing the primes on offer in the opening kilometres, he chose to line up near the front of the peloton and joined an attack launched just beyond the outskirts of Milan.

>>> Cycling Weekly is available on your Smart phone, tablet and desktop

There were five riders in it, the pick of them Coppi and Frenchman Lucien Teisseire, the peloton happy to let them ride away into a headwind on what seemed an ill-conceived move. When Teisseire pushed up the pace approaching the Turchino pass, Coppi was the only one able to follow. When Coppi attacked before the top of the pass, the Frenchman fell away, leaving the Italian alone with 150 kilometres to race.

Sensing something extraordinary, people turned out along the route to cheer Coppi on. He arrived at San Remo with his advantage on Teisseire an enormous 14 minutes, what remained of the peloton another four behind. "We’re proud of you!" was the headline on La Gazzetta dello Sport the next morning.

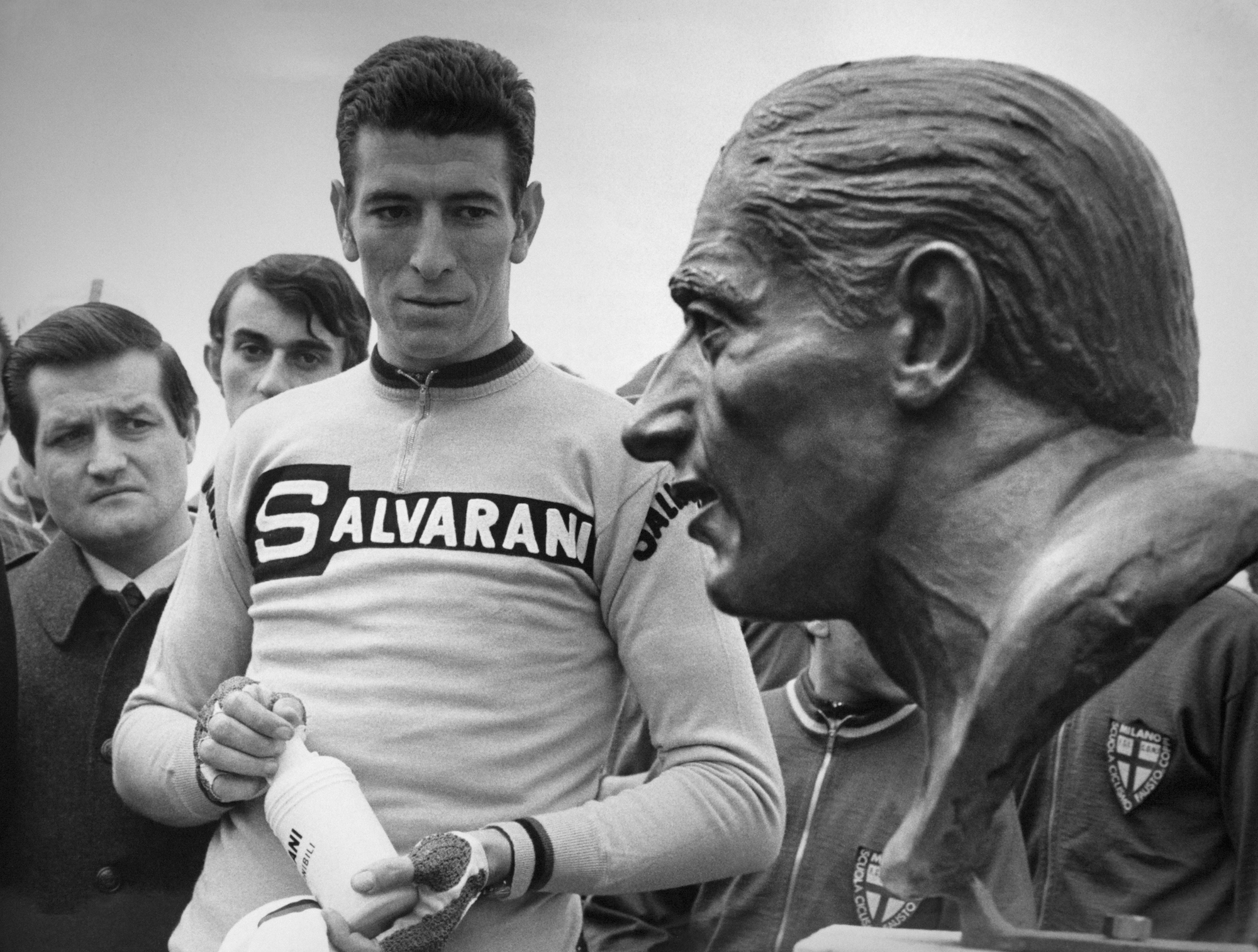

6. Tour of Lombardy 1966

When it comes to the quality of the group that contested the finish, few Classics can compare with the 1966 edition of the Tour of Lombardy, the race highlighting a change of generations as the young Eddy Merckx and Felice Gimondi contested the title with Jacques Anquetil, the presence of Raymond Poulidor adding even more piquancy to a hotly disputed finish.

Defending champion Tom Simpson had gone into the race as one of the favourites, but lost contact with the leaders 40km from home, leaving his young Peugeot team-mate Merckx leading the French team’s challenge. On the final climb at San Fermo della Battaglia, Gimondi attacked once, twice, three times, then a fourth and a fifth, but on each occasion, Anquetil responded.

The group entered the Sinigaglia velodrome in Como together. Up against Salvarani duo Gimondi and Vittorio Adorni, Merckx tried to boss the sprint from the front, but left a gap on the inside that Adorni darted through. When Gimondi came over him to lead out the sprint, Merckx responded only to find Adorni blocking the straight route to the line, the slight deviation this forced enabling Gimondi to clinch his second Monument after his victory in Roubaix earlier that season, ahead Merckx, Poulidor and Anquetil.

7. Tour of Flanders 2011

A thrilling race that featured all the best Classics riders of the time, most notably Fabian Cancellara and Tom Boonen, ended with one of the least heralded members of the front group upstaging the big guns to take a beautifully judged victory against the odds on the final occasion the Muur and Bosberg finale was used in Flanders.

The final 100 kilometres were packed with attacks and counters. Coming on to the Muur, Cancellara looked well placed for victory, having bridged up to join lone leader Sylvain Chavanel at the front. But the Swiss started to wilt, allowing a chasing group to make contact. Approaching the Bosberg another group containing Boonen, Geraint Thomas and Nick Nuyens also made it to the front.

After another series of attacks came to nothing, Cancellara made a final assault, Chavanel and Nuyens jumping across to him. As Boonen made a frantic late charge behind, Cancellara led out the sprint on the drag up to the line in Ninove, but Nuyens judged it better, passing the Swiss and holding on to take the biggest win of his career.

8. Paris-Roubaix 1977

Already the victor on three occasions, Roger De Vlaeminck became the first rider to win Roubaix on four occasions with an imperious performance that fully encapsulated his nickname as ‘Mr Paris-Roubaix’.

On a course beefed up with extra sections of cobbles, including the fearsome section at Orchies, De Vlaeminck was determined not to suffer the same fate he’d endured the previous year when he’d lost out in the sprint to Marc Demeyer. Eddy Merckx described De Vlaeminck as gliding across the pavé "as if he knew the position of every single cobble". On a section 25km from the finish, De Vlaeminck, his nose just above the twin peaks of his brake cables, increased his cadence and eased away from the 20-odd riders in the lead group. There would be no repeat of the bitter sprint defeat he’d suffered 12 months earlier.

9. Tour of Lombardy 2017

It is, as Thibaut Pinot found out, one thing knowing that a rival rider is likely to launch an attack at a particular point in a race, but another test entirely when it comes to responding to it. In 2015, Vincenzo Nibali had attacked on the descent from Civiglio to win his first Lombardy. Two years later, he was looking for a repeat.

Fully aware of the point where the Italian would likely make his move, Pinot jumped away from a small leading group climbing to Civiglio, only to have Nibali join him just before they reached the top. On the twisting and very technical descent, Nibali pushed his bike and himself very literally to the edge, his speed and skill too much for Pinot to contend with.

He raced towards the final climb at San Fermo della Battaglia with a lead of only a dozen seconds or so, but it was enough, as the group chasing behind failed to find the cohesion to chase him down.

10. Paris-Roubaix 2012

‘The Hell of the North’ first signalled Tom Boonen’s talent when he finished third behind Johan Museeuw on his debut in the race in 2002, and it was at Roubaix that he claimed the last of his seven Monument successes at the end of a stunning 52km solo break.

Boonen was part of a group of five who came together following the tough cobbled section at Orchies. Beyond it, Boonen and team-mate Niki Terpstra went clear, but the Dutchman was soon unable to follow the Belgian’s blistering pace and fell back to the chasers behind.

Despite having as many as 14 riders chasing behind him, Boonen managed to push his advantage slowly but relentlessly. When he exited the last difficult section at Carrefour de l’Arbre with a lead of more than a minute, the race was as good as won and Boonen was able to savour the adulation of the crowd as he completed the final lap and a half around the Roubaix velodrome.

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Cycling Weekly, on sale in newsagents and supermarkets, priced £3.25.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Founded in 1891, Cycling Weekly and its team of expert journalists brings cyclists in-depth reviews, extensive coverage of both professional and domestic racing, as well as fitness advice and 'brew a cuppa and put your feet up' features. Cycling Weekly serves its audience across a range of platforms, from good old-fashioned print to online journalism, and video.

-

Review: Cane Creek says it made the world’s first gravel fork — but what is a gravel fork, and how does it ride?

Review: Cane Creek says it made the world’s first gravel fork — but what is a gravel fork, and how does it ride?Cane Creek claims its new fork covers the gravel category better than the mini MTB forks from RockShox and Fox, but at this price, we expected more.

By Charlie Kohlmeier

-

ROUVY's augmented reality Route Creator platform is now available to everyone

ROUVY's augmented reality Route Creator platform is now available to everyoneRoute Creator allows you to map out your home roads using a camera, and then ride them from your living room

By Joe Baker

-

What happened to Johnny Hoogerland?

What happened to Johnny Hoogerland?A career defined by a collision with a TV car at the 2011 Tour de France, we tracked down the Dutch rider to find out how the next 10 years unfolded

By Jonny Long

-

From Gaza to the Giro d’Italia – the many faces of Israel Start-Up Nation

From Gaza to the Giro d’Italia – the many faces of Israel Start-Up Nation“Thank you for the question, because this is so dumb,” says Canadian billionaire Sylvan Adams, who has just touched down from Miami and is sat in the lobby of a beachfront hotel in Tel Aviv.

By Alex Ballinger

-

'The domestiques on our team are unsung heroes': Owain Doull Q&A

'The domestiques on our team are unsung heroes': Owain Doull Q&AThe Olympian and Team Ineos man on his Maindy roots, staying motivated and passion for coffee

By David Bradford

-

What will happen to pro cycling? Exploring the economic landscape after coronavirus

What will happen to pro cycling? Exploring the economic landscape after coronavirusFrom the fate of various WorldTour teams to whether a behind-closed-doors Tour de France actually solves anything

By Jonny Long

-

Is there a best time to train? A sports scientist investigates

Is there a best time to train? A sports scientist investigatesMost of us ride our bikes whenever we get chance, but is there a best time of day when you’ll unlock the most potential and make maximum gains? Sports scientist Dr Mark Homer investigates

By Cycling Weekly

-

Five of the all-time best Classics rides by Brits

Five of the all-time best Classics rides by BritsFrom Tom Simpson to Lizzie Deignan

By Cycling Weekly

-

Sweet success: How I won Red Bull Timelaps as a diabetic rider

Sweet success: How I won Red Bull Timelaps as a diabetic riderType-1 diabetic George Kirkpatrick is on a mission to prove that compromised blood sugar control is no barrier to success — however long the race

By David Bradford

-

Can Chris Froome recover to win a fifth Tour?

Can Chris Froome recover to win a fifth Tour?After a horrific crash, Froome’s road to recovery has not been easy. James Shrubsall assesses the hurdles he’ll need to overcome to wear yellow in Paris this July

By James Shrubsall