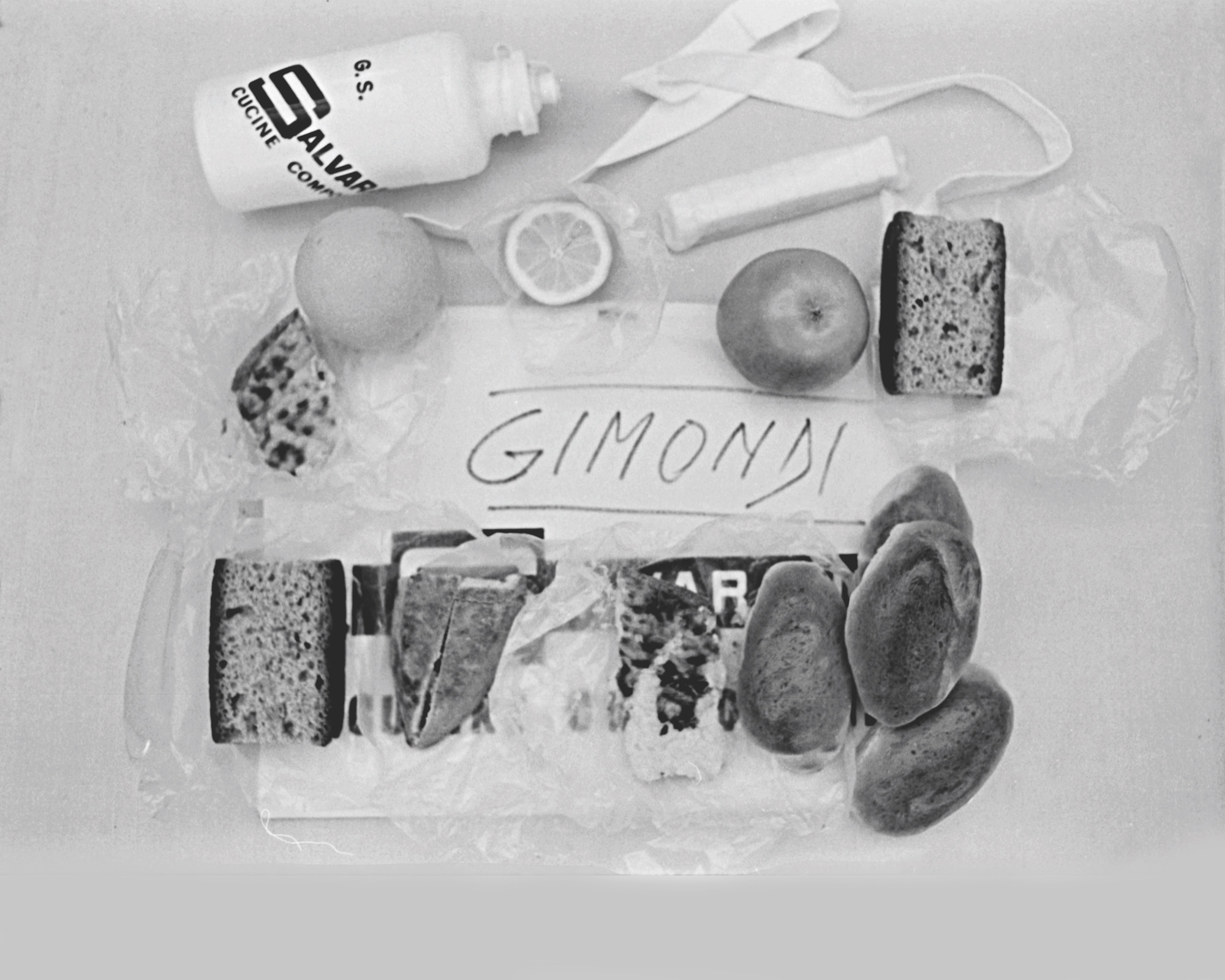

'I liked to smoke a cigarette during the Tour de France, it calmed my nerves': Cycling nutrition before bread and water

Early bike racers shunned bread and water in favour of steak and booze. Chris Sidwells pulls up a seat at the retro banquet

Vittorio Adorni, Jacques Anquetil and Felice Gimondi eating spaghetti during the 1966 Giro d'Italia (Photo by Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

Salty dried herrings, rare steak, red wine with sugar, pigeons, weird fruit and vegetable concoctions, even tobacco and hard liquor – they’ve all been part of the diet of a pro cyclist. There were things that had to be avoided, too: tap water, chips, the middle bit of baguettes and oranges after 6pm. These nutritional guidelines were part of the professional cyclist’s code ‘Le Métier’, handed down the generations and known only by insiders. It was a very different world.

When cycling emerged as a sport, towards the end of the 19th century, long-distance races soon began to catch the public’s attention – events such as the 360-mile Bordeaux-Paris and the 750-mile Paris-Brest-Paris, both ridden in one go rather than in stages, unlike the later Tour de France. Long races required lots of fuel, but competitors ate normal meals. Even during races, there were sit-down feeds, although some innovators, usually the best riders,

soon began to do things differently.

Take the British winner of the first Bordeaux-Paris in 1891, George Pilkington Mills, a long-distance record holder, who was invited to take part with three of his club-mates. The foursome broke away from the start, and sat down to bowls of soup at the first feed. Come the next stop, however, Mills was determined not to waste time, stopping long enough only to "swallow a dog-mouthful of finely chopped meat and drink a bottle of specially-prepared stimulant" – according to reports. The rest of Mills’s food was handed to him by his pacers, and a trend was started. By the first Tour de France in 1903, the leaders hardly stopped at all, carrying food in pockets and bags. It was still normal food, though – cheese and ham baguettes and cake.

Steak for breakfast

Protein featured heavily in the Edwardian cyclist’s diet. Steak with rice was a breakfast staple. The 1909 Tour de France winner François Faber could eat six steaks in one go, while Canadian track specialist William Peden preferred full roast dinners during lulls in epic Madisons.

>>> Subscriptions deals for Cycling Weekly magazine

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Steak remained part of a pro racer’s diet for many years. Riders still ate steak or veal for breakfast in the Eighties, and by then, Métier contained all sorts of weird and wonderful beliefs. Lots of attention was placed on liver – no, not to eat, but the rider’s own. Seasoning and sauces were thought to irritate this vital organ, so top cyclists like Fausto Coppi ate only plain foods. Coppi also drank liquidised vegetables, again to save his liver and other organs from doing too much work.

Sex, drugs and alcohol

Although sex was discouraged by team managers, drugs and alcohol were part of day-to-day life in the pro peloton. A banned substance list wasn’t introduced to cycling until 1965, with testing and punishment lagging far behind. Riders found breaking the rules wasn’t vilified, so banned substances were an integral part of being a serious pro. Not everyone partook, but plenty did.

Alcohol was drunk in early races to help numb the pain of hours in the saddle. It remained part of bike racing because, hard to believe now, opportunities to rehydrate were restricted by race rules. Tour de France riders could carry drinks and take bottles at feed stations, but dropping back to team cars for drinks was forbidden. Dehydration was common; some even believed it was better to race dry. "Driest is fastest," said the five-time Tour winner Jacques Anquetil, who broke every dietary rule there was.

Riders drank little during training, hoping to condition their bodies to handle what we now understand as performance-limiting dehydration. Some Belgians even ate dried salted herrings, thinking that helped. Racers carried on drinking alcohol because they got so thirsty during races that they raided cafes and took bottles of cold beer to drink and share with team-mates. In doing so, they became experts in removing bottle tops on the expander bolt of their handlebar stems.

Saving weight

The belief that hard miles meant heavyweight foodstuffs lasted for a long time. It’s changed now, of course, especially for stage-race specialists, who count calories like supermodels to reduce their body fat. Power-to-weight ratio is everything to them; once well trained, there isn’t much more a mature pro can legally do to increase power – minimising weight is the only remaining gain. As with Mills and feed stops, the pioneering early racers twigged the link between weight and winning.

Louison Bobet, the first to win three Tour de France titles consecutively, lived like a monk to get his weight as low as possible for big stage races. Testament to the effectiveness of Coppi’s ascetic eating habits, his rival Gino Bartali said that seeing Coppi naked was "like looking at a skinned cat".

Even Eddy Merckx has acknowledged that it took him a while to realise the importance of getting lean: "When I was young, I thought nutrition was simple. I worked hard on my bike, so I ate lots to stay strong. It was only when I had Italian team-mates in 1968 that I began to see how important body weight was."

An authoritative team-mate opened his eyes. "Vittorio Adorni was influential – he was older than me and had won the 1965 Giro d’Italia. He told me the best exercise to lose weight was a two-handed push away from the table.

>>> Cycling Weekly is available on your Smart phone, tablet and desktop

"He meant I should try to eat just enough, then leave the table without feeling full. I did what he said, lost a couple of kilos, then won my first Giro in 1968 and my first Tour de France in 1969."

Merckx was a modern champion who applied science to his sport, except for one bad habit: "I liked to smoke a cigarette, even during the Tour de France. It calmed my nerves." Barry Hoban, who won eight stages of the Tour de France in the Sixties and Seventies, talked us through his dietary regime from back in the day: "After each season ended, I would purge my system – I’d have a week where I would refresh my liver and my kidneys. For the first three days, I ate nothing and I drank a kind of Alka-Seltzer, a really alkaline water. I didn’t do anything physical at all, just lounged around and relaxed.

"On the fourth day, I started eating fruit: oranges, grapefruits, tomatoes, that type of thing. You could also drink certain herb teas. I drank cherry leaf, and blackcurrant leaf tea. By the end of the week, I was eating salads of grated carrots with celery, but no fancy dressings at all. Then you started training.

"For the rest of the time, I tried to eat plenty of good, wholesome food, but it was hard to eat well on some stage races. You were ok on the Tour de France, but we still made our own simple salad dressing and we never ate the centre of white bread – two of our beliefs. The evening meal would be meat and usually rice, then a light dessert. But in other races, the Vuelta for example, the hotels weren’t so good.

"Spain in the Sixties wasn’t the Spain of today. Hotels inland were poor and their kitchens were terrible. I took a big bag of my own muesli mix to all my races, so I could have a good breakfast, but when I saw what came out of some hotel kitchens, I’d just eat the rice. I’d ask to boil a couple of eggs, then mix the eggs with the rice, grate some cheese on top and eat that. I’ve ridden entire stage races on just muesli, rice, eggs and cheese."

This feature originally appeared in the print edition of Cycling Weekly, on sale in newsagents and supermarkets, priced £3.25.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Chris has written thousands of articles for magazines, newspapers and websites throughout the world. He’s written 25 books about all aspects of cycling in multiple editions and translations into at least 25

different languages. He’s currently building his own publishing business with Cycling Legends Books, Cycling Legends Events, cyclinglegends.co.uk, and the Cycling Legends Podcast

-

Save £42 on the same tyres that Mathieu Van de Poel won Paris-Roubaix on, this Easter weekend

Save £42 on the same tyres that Mathieu Van de Poel won Paris-Roubaix on, this Easter weekendDeals Its rare that Pirelli P-Zero Race TLR RS can be found on sale, and certainly not with a whopping 25% discount, grab a pair this weekend before they go...

By Matt Ischt-Barnard

-

"Like a second skin” - the WYN Republic CdA triathlon suit reviewed

"Like a second skin” - the WYN Republic CdA triathlon suit reviewed$700 is a substantial investment in a Tri Suit, and it is, but you’ll definitely feel fast in it

By Kristin Jenny