Lotus x Hope HB.T: Team GB's track bike in detail

British Cycling's UKSI bike is a thing of legend, so when Hope dropped the new British track bike on us at the end of 2019 we knew we had to go and take a closer look at the story behind it. Michelle Arthurs-Brennan travelled to Hope's factory in Barnoldswick to find out more.

This article was first featured in Cycling Weekly magazine, in January 2020

Future gazing is always fraught with risks. The list of technological innovations that purported to tip the world on its head and were swiftly consigned to the skip of history, we’re looking at you Betamax, is long. But the creators of the unconventional Hope/Lotus bike that’ll carry British hopes into the Tokyo Olympics is a “milestone in the evolution of bikes”.

>>> Essential guide to Olympic track disciplines

Around 40 people were involved in the development of the “Marmite” machine, including several veterans who made up the design team for the UK Sport Institute (UKSI) bike raced to victory time and time again in 2004, 2008 and 2012.

However, this swaggering hulk is a completely new beast and one with big shoes to fill. Most strikingly, the bike features 8cm wide forks and seatstays - with the goal of channelling air more efficiently around the rider’s legs.

“I’d abolish all bikes and make sure that they’re all based on this concept going forwards, though I’m not sure that everybody would agree with me,” British Cycling’s director of technology, Tony Purnell tells Cycling Weekly.

BC’s technical director since 2013, Purnell says the initial concept came from a searching for space for creativity within the UCI rulebook.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“We knew we had to create something really special. But the rules were pretty restrictive! There was almost nothing we could do. We realised the only scope [for creativity] was that there were no real width restrictions.”

There is a finite limit – but at 50cm, it gave the design group quite a lot of space to play with.

“I did some research, all fundamental stuff, and drew a sketch on the whiteboard. From that sketch, suddenly it all became real. We cobbled a bike together from sawn up bits of old bikes, and original tests in the windtunnel looked pretty promising,” Purnell says.

Discussing the design process, Hope design engineer Sam Pendred notes the distinction between the method used to create this bike, and what goes on elsewhere. “You can design a very aerodynamic bike – but as soon as you put a rider on it, you create massive problems for yourself! The largest effect on aerodynamics comes from the rider. If you address that issue from the start – turning the question on its head to ‘how can we make the rider more aerodynamic?’ – you design a package.

“The whole thing works as a unit. The wide forks and seatstays align with the rider’s legs, it’s all aimed at channelling the air more effectively.”

Opinion was divided from the start: “One of our more elder statesmen saw the bike and said ‘that’s ridiculous there’s no way that’s going anywhere!’ Then we had a young lad come in the next day and he said ‘Wow! That’s different! All bikes are going to look like that in 5 years time!” recalls Purnell

“From that moment on it was always going to be a ‘Marmite bike’.”

Creating Team GB's track bike: crucial combos

There are several factors involved in the aerodynamic difference between this bike and another – for example, since the seatstays are designed to mirror the rider’s legs, this machine will be more effective for some than others. However, estimations suggest it’s around 2-3% faster than previous track racing bikes.

In terms of individual difference, the team tested a range of bike and rider duos in the windtunnel.

“We effectively tested two ends of the spectrum” says Pendred. “We tested riders with size 12 feet, and people with different cleat positions, to make sure that the two extremes of physiology can be catered for in this design.”

While that 2-3% advantage could be massive, a lot of the boost will go on in the heads of others, according to Purnell. “We know that getting any tangible performance [gain] is going to be very difficult at this point in bike design... but just having something that’s strikingly different [could] go down very well because there’s a lot of psychological wars that go on.

“If other nations are gazing at something that’s caused a lot of flap in the cycling world then they might just feel a tad envious. And that would be great!” he says.

Among the people who have been involved in previous GB track bikes that have been involved in the design are Demitris Katzans, who worked on the structural side, and composite expert Chris Clarke, who is working at the Hope Factory to lay carbon into the moulds.

However, despite all that knowledge, starting any design with a blank whiteboard brings its own challenges. “Most engineering tasks are redesigns; you use all your previous calculations. But this machine is a 100% complete redesign of what’s come before. When you throw it all away and start again it’s much harder,” says Purnell.

The challenge was accelerated when the UCI brought the deadline forward by nine months - requiring the bike to be raced before December 2019.

“Cutting nine months off the programme didn’t half force our decision making!” Purnell confirms. “It meant we couldn’t try 10 little changes to see what works best, we just had to go with it.” That lack of fine-tuning, he believes, represents a lot of potential for the future. “I’d love to think that we could carry on and make something more of this. I think that there’s real potential for it to be a better road bike, time trial bike, and track bike.”

Creating Team GB's track bike: three become one

Getting the bike from a whiteboard to rolling around a velodrome required a trio of tech companies: Lancashire brand Hope created the frame and wheels, Lotus stepped in to develop the forks and handlebar, whilst Renishaw offered 3D printing support.

“There’s a really large number of people who have made a contribution to this bike. If I include the designers, laminators, structural engineers wind tunnel technicians, the team at BC, you can put 40 names on the page. Each of those names have made a definite contribution to the project. It tells a great story about the engineering process and what’s possible in the UK,” Purnell says.

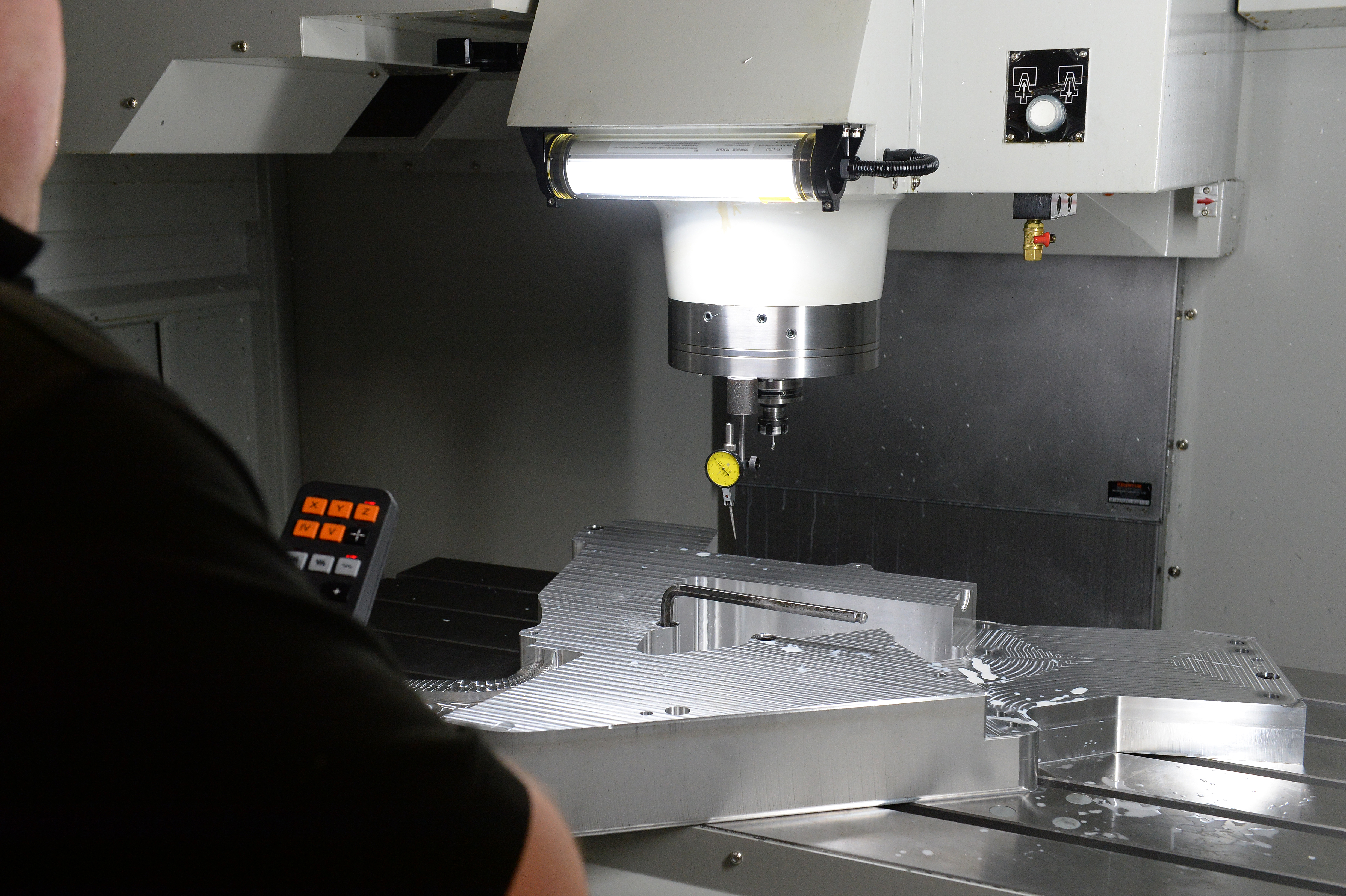

Hope was initially of interest for their mountain bike design capabilities – but when Purnell visited the factory and saw the technology available, it became clear that they could be of immense use in the track project, too. The 1989 founded company is renowned for its CNC-ed aluminium components, but with the capacity to CNC its own moulds it was clear that the Barnoldswick facility could create pretty much anything the design team needed.

“Making your own moulds is not something you see a lot in the industry. But for us, it’s the easiest – aluminium is what we’re known for,” says Hope’s Alan Weatherill. Each mould takes approximately one month to cut, and there will be five in total, with five complete frame sizes and eight variants made possible by joining separate pieces together.

Hope has also developed a new wheel building method. The disc wheels are created in one piece – resulting in a lighter and stronger construction.

“Having the tools we have in house, we’ve managed to develop a way we can create the disc wheel in the mould in one piece of carbon, as opposed to making it in pieces and bonding them together,” says Pendred.

The two sides are joined continuously, including the centre tube of the hub as well. Visiting the factory, CW was able to peer into a disc, cut in half. The creation looks much like a pitta bread, fresh from the toaster.

“You save weight by reducing the bonding agent you’d otherwise have to use on something that is quite light in the first place.”

Almost all the work happens in the mould, explains Pendred: “You can machine the tool to high tolerances, once you’ve got that right once, you’ll get parts out of it that are right every time. If you can reduce the amount of post processing you have to do on it, there’s less chance of it going wrong and you can actually make a better part, more consistently.”

And yes, Pendred confirmed that – once the Olympics are out the way – disc wheels for time triallists are the next logical progression, the company will be looking at.

Aside from the forks and bars coming from performance car company Lotus, precision manufacturing company Renishaw were and essential component to the bike’s development. Some of the more elaborate small parts were made possible with their 3D printing expertise.

For Hope, the control afforded by this process was a major draw.

“3D printing offers a great way to manufacture complex junctions – such as the area where the seat tube meets the seatstays. It also has the added potential of rib structures – you can take weight out of certain areas and add ribs in others. And, you’ve got a lot more control over how you design internal structures within it – so you can make a lighter part, stronger.”

Strength is a pretty fundamental for a bike that will have to withstand the sprinting force of the best GB has to offer.

“Some of the riders are putting out up to 2,500 watts especially out the start gate, there’s a serious amount of power going through it, that was taken into account in the layup,” Pendred says.

While the seat stays weigh in at just 70g and – before they’re affixed to the bike – I can pick them up and wobble them around like a bowl of jelly, areas such as the bottom bracket shell and headtube have been beefed up to cater for some serious torque.

The bike made its first outing at the Minsk World Cup in November, and the goal is that all riders are able to climb aboard by spring ahead of the Games in July.

“Working for the British team is like working at the Enigma Code, you’re constantly under pressure” Purnell says. “If you don’t do a good job, you’ve failed. That’s where the British team is. Sometimes I think we can’t succeed anymore, we can only fail. And that’s just because we’ve done so well over the last decade.”

At this point in development, Purnell believes that real ground breaking innovation is essential: both in helping Team GB achieve the success it needs, and in moving bike design forwards.

“When we began this project, we concluded that we were pretty pleased after Rio [in 2016] – and that conventional bike design had come a really long way. To get any kind of substantial step forward with it was pretty damn unlikely.

“Whenever I hear someone say track racing should all be done on an old, Eddy Mercx style standard bike, I can see their point… but I think it would damage cycling pretty badly if we became luddite. I tingle with excitement that perhaps this is just a little tiny milestone in the evolution of bikes.”

Creating Team GB's track bike: the numbers

- 2-3%: How much faster the bike is than a conventional design

- 2,500 watts: Max power the bike was developed to withstand

- 5: Number of moulds created, with 8 frame sizes available

- 70g: Weight of the unpainted seat stays

- £21,700: Estimated price for a complete pursuit bike

All in the carbon

Chris Clarke lays the carbon into the moulds by hand

“The first Olympic track bike I was involved in was before Beijing, in 2008. I worked on the bikes in 2012 too, and in 2016 [when Cervelo made the GB track bikes] I made the tandems and wheels.

The carbon is very fragile – it’s lighter and stiffer than the carbon we’d use on he Hope mountain bikes, that material needs to be tougher and not as stiff. The stiffer it gets, the more the strength drops. The carbon we’re dealing with here is easy to break if you don’t handle it carefully.

“The layup doesn’t change across the sizes. There’s discussions as to whether that should be the case or not, we’re still in that process. A typical approach would be to use more carbon on the bigger models, but at the moment it’s not something we’re doing.

The seatstays weigh just 70g. Image: Andy Jones

“The seatstay weight 70g. It is structural, but you want them as light and thin as possible. Most of the strength is down in the chainstay, which is why this is so much bigger.

“A lot of force goes through the front end. It’s surprising how much, when you see the slow motion pictures. There’s quite a lot of material around here, and the same applies at the bottom bracket.

“It gives me a big sense of pride to see the Olympic riders racing a bike I made. When you see them going around… especially when they’re winning gold medals, that’s even better.”

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her first daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

Michelle is on maternity leave from April 2025 until spring 2026.

-

I have been capturing my cycling adventures for over 20 years, and two of the best action cameras for cyclists have just hit their lowest prices on Amazon

I have been capturing my cycling adventures for over 20 years, and two of the best action cameras for cyclists have just hit their lowest prices on AmazonDeals Amazon has slashed the price on Insta360 cameras, including the highly rated X3, which has a huge 30% off

By Paul Brett Published

-

'I've already lost 2 kilograms and my head feels clearer': I'm a month into sober curiosity and have never felt so good on the bike

'I've already lost 2 kilograms and my head feels clearer': I'm a month into sober curiosity and have never felt so good on the bikeBeginning to fear for his health, Steve Shrubsall swapped beer and telly for turbo sessions and books, here’s what happened

By Stephen Shrubsall Published

-

UCI Track Champions League cancelled after four years

UCI Track Champions League cancelled after four yearsCommitment to track cycling series proves short-lived as it is axed prematurely

By Tom Davidson Published

-

Matthew Richardson breaks world record, UCI rules it out

Matthew Richardson breaks world record, UCI rules it outBrit's flying 200m time voided after exiting the track during his effort

By Tom Davidson Published

-

Why hasn't GB sent a full squad to this year's only Track Nations Cup?

Why hasn't GB sent a full squad to this year's only Track Nations Cup?Eight riders will represent GB in Turkey this weekend, with the women's endurance squad left at home

By Tom Davidson Published

-

Class of 2025: Meet the 12 British cyclists who turned pro this year

Class of 2025: Meet the 12 British cyclists who turned pro this yearA bounteous 12 Brits have stepped up to the pro ranks in 2025. Tom Davidson traces the skyward trajectories of a former runner, an adoptive Italian, and the WorldTour’s youngest rider

By Tom Davidson Published

-

Matthew Richardson seals clean sweep on British National Track Championships debut

Matthew Richardson seals clean sweep on British National Track Championships debut"Being part of the racing makes me feel British," says Richardson, who previously represented Australia

By Tom Davidson Published

-

'I completely blew my doors' - Katie Archibald wins first national track title in six years

'I completely blew my doors' - Katie Archibald wins first national track title in six yearsDouble Olympic champion enjoys "nice reset" on National Track Championships return

By Tom Davidson Published

-

'I almost didn't race' - Amateur with broken elbow wins gold medal at National Track Championships

'I almost didn't race' - Amateur with broken elbow wins gold medal at National Track ChampionshipsNiall Monks defied doctor's orders to win his first national title

By Tom Davidson Published

-

'It's going to keep coming down' - Anna Morris breaks world record for a third time in the individual pursuit

'It's going to keep coming down' - Anna Morris breaks world record for a third time in the individual pursuitWorld and European champion adds national title to her honours

By Tom Davidson Published