The Col de Joux Plane: the Tour de France's forgotten climb?

In the shadow of the mighty Mont Blanc, the Col de Joux Plane could be the small climb with the big story at the 2016 Tour de France

The Col de Joux Plane. Photo: Daniel Gould

There are always two sides to every story. On the one hand the Col de Joux Plane is perhaps the most picturesque and tranquil mountain pass in the French Alps. Nestled in the shadow of Mont Blanc, it’s a postcard of bucolic beauty, sun-drenched in the summer and sprinkled with snow in the winter.

On the other, this inauspicious place has borne witness to cycling miracles, not to mention more than its fair share of daredevilry and tragedy.

It even claimed the scalp of Lance Armstrong 13 years before the US Anti-Doping Agency and Oprah Winfrey got round to it.

Less than 1,700m at the top and less than 12km in length, this diminutive, deceptive and oft-forgotten Alpine pass has played theatre to cycling high drama and will play the role of the decisive mountain on stage 20 of the 2016 Tour de France.

Coming as the final climb on the final mountain stage in this year’s race, the climb will see the final battle for the yellow jersey before the race heads to Paris the following afternoon.

>>> Tour de France 2016 route and essential guide

Just as there are two sides to every story, there are two sides to every mountain; in order to conquer this one the riders of the Tour will have to go up the Col de Joux Plane and then down

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

the other side again.

Bottles and battles

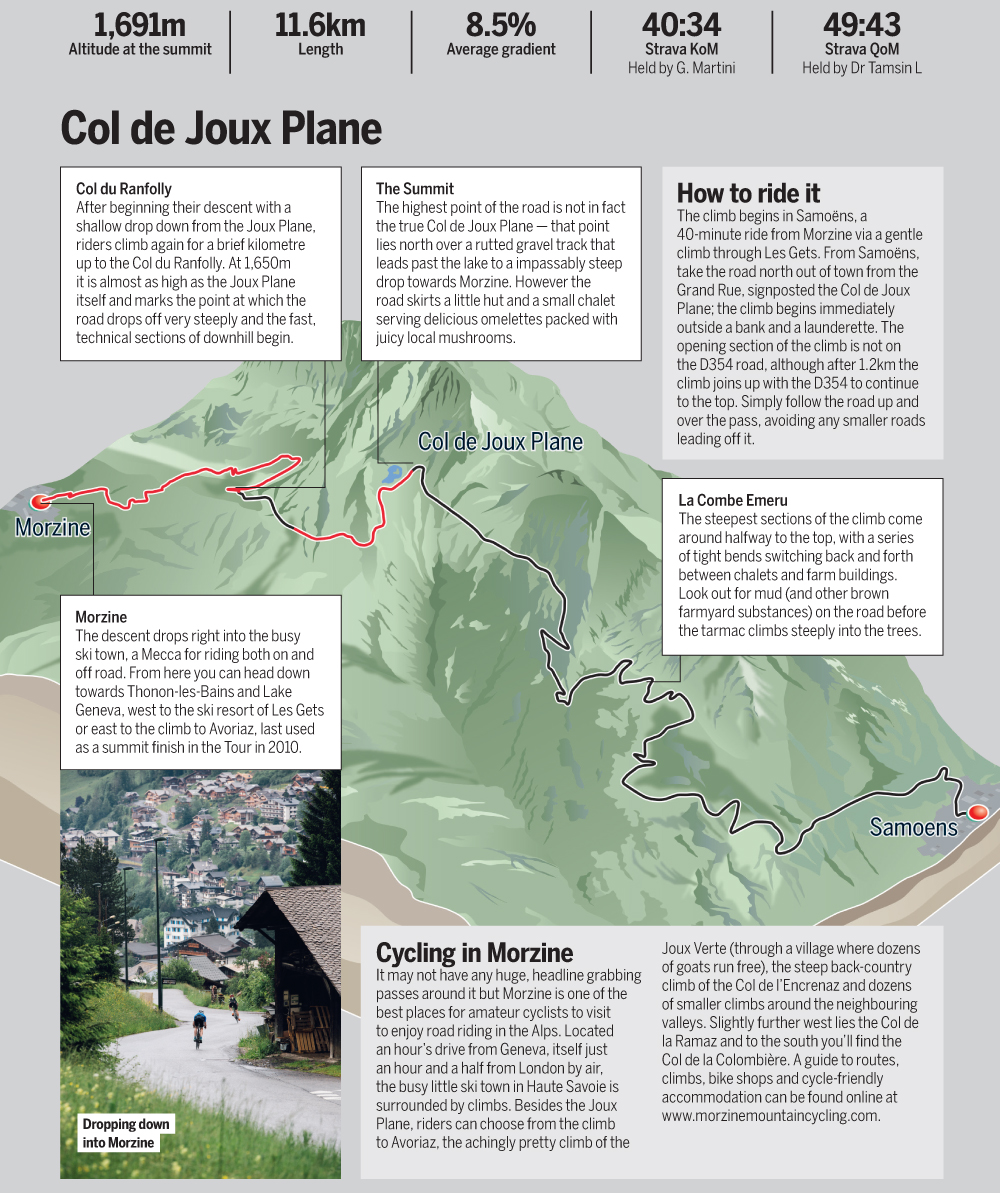

There are a few chalets and farms dotted along the lower and middle slopes of the southern face of the Col de Joux Plane, which is the route the Tour de France has taken to the top on every one of the 11 occasions it has visited.

In almost every respect this is the perfect place to live; the verdant wild-flower meadows hum with grasshoppers in the summer while around them the cows munch away on the thick grass.

The pretty little town of Samoëns sits at the bottom of the mountain and in winter, good skiing is less than half an hour away.

You almost have to be reminded of how close you are to the great mountain grands cols of the Alps; this place feels far removed from the sublime snowbanks of the likes of the Stelvio, Galibier and Grand Saint Bernard.

There’s even a little lake at the top with ducks swimming around on it, and the flattened corpses of newts and frogs on the road suggest that the only things hostile to life up here are humans and their four-wheeled vehicles.

>>> Icons of cycling: Shimano Dura-Ace 7800

But the Col de Joux Plane is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Beneath the exterior is a climb worthy of its fearsome reputation. Just ask Lance Armstrong.

OK, so riders, professional or amateur, don’t like to dwell on Big Tex too much these days, but cast an eye back to July 18, 2000, and stage 16 of that year’s Tour.

Armstrong suffered on a day he called “his worst I’ve ever had on a bike,” losing two minutes to Richard Virenque in a matter of five kilometres after he was dropped on one of the steepest sections of the pass, the 13 per cent approach to the collection of houses that goes by the name of La Combe Emeru.

>>> Does EPO actually boost cycling performance?

“I had a lot of emotions. I was hungry, I was light-headed, I was nervous, I was scared,” he said. “I could have lost the Tour de France.” Armstrong could easily have added ‘hot’ to his list of discomforts, for this climb — which features some of the most consistently steep gradients of any of the Tour’s Alpine passes — is south facing and low in altitude.

It’s not always bright sunshine — when Cycling Weekly visited in early June the road was pounded with intermittent thunderstorms bubbling over from one of France’s wettest weeks on record — but in 1983 Laurent Fignon battled to keep the race lead on the Joux Plane’s slopes, dripping with moisture like a yellow flower in a tropical greenhouse at Kew Gardens and squeezing his thighs at 55rpm like he was kneading bread dough with his feet.

>>> Icons of cycling: L’Auto, the newspaper that launched the Tour de France

Just ahead of him the Colombian Edgar Corredor had pulled his jersey up and tucked it around his waist in a desperate effort to get some cooling to his torso, while Peter Winnen and Phil Anderson looked like they had just stepped out of a swimming pool.

They had in fact grabbed big bottles of water from the spectators on the side of the road and emptied them over their heads.

What did for the riders of the mid-80s as much as anything was the Joux Plane’s irregular gradients. If you’re not permanently stuck in the biggest sprocket, a fast time requires shifting several times between each hairpin bend to deal with the dips and ramps. You try doing that with down tube shifters and an 11-22t cassette.

Talking of fast times, Marco Pantani’s chemically-enhanced record was 33 minutes but these days anything under 45 minutes is very, very good going.

Setting records will be a long way from the minds of the riders of the Tour though — this year the climb will be tackled on a 146.5km short mountain stage with the fatigue of the cols of the Aravis, Colombière and Ramaz (not to mention 19 days of racing) throbbing in the riders’ legs.

This is true for not just the Tour peloton; on July 10 the Joux Plane will form the final challenge for 15,000 riders of the Etape du Tour, which traces the same route as that penultimate stage.

Peculiar homage

Since it first featured in the Tour in 1978, the Joux Plane has tended to reappear twice per decade. However 2016 marks 10 years since the last time the Tour came to visit; a somewhat ignominious anniversary given that the last protagonist of the climb owed his performance to a lot more than just bar-mounted shifters and a polyester jersey.

>>> UCI and WADA obtain samples from Operation Puerto blood bags

It was the year of Floyd Landis and the Operacion Puerto drugs bust spilling open like Pandora’s box in the weeks prior to the 2006 Tour de France, and implicating pre-Tour favourites Ivan Basso and Jan Ullrich, who were banned from the race.

Once the Tour had actually got underway Landis, who had endured a day of défaillance over the previous mountain stage to La Toussuire, embarked on a miraculous solo breakaway over four passes and finally the Joux Plane to retake the yellow jersey into Morzine, the town at the foot of the northern slopes of the climb.

>>> Plans to use pro cyclists’ power data to help stop doping

In returning 10 years on, 2016 will be a peculiar homage to one of the most existentially critical points in professional cycling’s history.

Perhaps this year will be the time to expunge memories of a decade ago and wash clean the reputation of the Joux Plane, stained with the yellow, green and ginger of the Phonak team’s American climber.

Triumphs and tragedies

We tend to think of mountain climbs in terms of going uphill but to conquer the Joux Plane means climbing up and descending back down again.

Indeed the climb has never hosted a summit finish; whenever the race has come by, the stage has always finished in Morzine, with barely two kilometres of flat between the descent and the line.

>>> Another look at Froome’s decisive Tour de France attacks (videos)

It sometimes takes a high-speed descent to pick out the irregularities in gradient, surface and rhythm that are hiding in plain sight when travelling uphill at less than 10mph.

The Col de Joux Plane reveals itself to be a rollercoaster of a trip back down to earth; the road dips, dives and swerves through woods and wiggles through meadows before plunging off a steep ledge overlooking Morzine.

Nipping through the houses (careful you don’t end up somersaulting into someone’s front garden) the road only levels out once it hits a roundabout in the middle of town.

With no regular hairpin bends to speak of, technical sections — such as two fast straights interrupted by a sweeping series of four bends around halfway down — seem to emerge out of nowhere.

There’s also the small matter of the road surface, which varies between new blacktop to cracked and pitted asphalt and to disturbingly wobbly waves of off-camber edges where the road seems to have sunk into the soil.

Knowledge is the key to success. The Tour de France’s key GC contenders all took time to recce the climb and descent during May and June, and Nairo Quintana (Movistar) remembers the climb from the 2012 Critérium du Dauphiné when he attacked over the summit, descended alone and won in Morzine.

However none will come close to knowing it as well as Jacques Michaud. The Frenchman who grew up less than 40km away on the outskirts of Geneva, now 64 and a former DS with BMC Racing, won alone in Morzine after cresting the Joux Plane at the head of the Tour in 1983.

He was also Floyd Landis’s team manager when he pulled off his stunt in 2006, but unsurprisingly Michaud doesn’t want to talk about that as much as he does his own victory 23 years earlier. The crucial knowledge, he says, is of when the corners will open up and when they won’t — of where you can carry speed and where you can’t.

>>> Five things to look forward to in the final week of the Tour de France

“It’s a very technical descent,” he says. “When I won I was alone in the break. In front of me on the descent there were a lot of motorbikes, team cars and so on, but after just a few corners I was right on top of them. I had ridden it so many times before, and so straight away I attacked into the corners and I hardly touched the brakes.

“There are a lot of corners with very tight curves but I knew that with most of the corners you don’t have great visibility, and someone in a car brakes a lot when the corner actually isn’t too bad.

“On that day I set the fastest time down because I knew the descent. When I crossed the summit I had 45 seconds lead and then at the finish in Morzine it was 1-15. So I gained 30 seconds, and the guys behind were going flat-out.”

>>> Which Tour de France team has the largest budget?

Boasting about descending skills on the Joux Plane clearly caught on, because a year later Sean Kelly claimed to have hit his all time record speed of an eye-watering 124kph (or 77mph in old money) on the way down.

But that year also showed the fine line between triumph and tragedy. Pedro Delgado crashed out to a broken collarbone and the Italian Carlo Tonon collided with a spectator riding uphill with such force that it left him with a fractured skull. In a coma for two months, Tonon — then 29 — woke up with a permanent mental disability. He committed suicide 12 years later aged just 41.

Conquer any climb

Grand finale

Although it’s been 10 years since the last visit, the Joux Plane fits perfectly with the modern Tour’s invented tradition of eschewing the vast high mountain passes in favour of smaller climbs, quirky finishes, and unpredictable and previously unpractised stage formats.

Race organisers will be hoping that this year the climb and descent of the Joux Plane provides upset in a more positive sense than some of the events in the climb’s history; with its position as the final curtain call on the race for the overall yellow jersey and the unique challenge it presents means there is more than a good chance that it will.

Riding the Col de Joux Plane

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Richard Abraham is an award-winning writer, based in New Zealand. He has reported from major sporting events including the Tour de France and Olympic Games, and is also a part-time travel guide who has delivered luxury cycle tours and events across Europe. In 2019 he was awarded Writer of the Year at the PPA Awards.

-

Review: Cane Creek says it made the world’s first gravel fork — but what is a gravel fork, and how does it ride?

Review: Cane Creek says it made the world’s first gravel fork — but what is a gravel fork, and how does it ride?Cane Creek claims its new fork covers the gravel category better than the mini MTB forks from RockShox and Fox, but at this price, we expected more.

By Charlie Kohlmeier

-

ROUVY's augmented reality Route Creator platform is now available to everyone

ROUVY's augmented reality Route Creator platform is now available to everyoneRoute Creator allows you to map out your home roads using a camera, and then ride them from your living room

By Joe Baker