Winning from the break: every racer's dream

Winning from a breakaway is still every racer’s dream despite the stifling impact of technology

Tony Martin during a long but unsuccessful breakaway. Photo: Graham Watson

Few can forget the sight of Jack Bauer exhausted and slumped on the floor by the barriers at the 2014 Tour de France, head in his hands and crying, having been caught by the peloton within 25 metres of the finish line, after spending all of the day in a two-man breakaway.

The New Zealander’s raw emotion epitomised the challenge facing riders attempting the long-distance escape. Some may last until 20 kilometres to go, others may hang on all the way to the flamme rouge, but the majority will be caught before the end — the odds of survival are rarely ever in the breakaway’s favour.

It has become almost standard practice for a break to be let go, only for the peloton to gradually reel it back in as the kilometres tick away, and the ‘real’ racing begins at the end of the stage.

In fact, out of the 130 days of road racing in the WorldTour in 2015, only 26 races were won by a rider from the break. Even at last year’s Tour de France just five of the 18 road stages saw victories from a breakaway. Could it be that the time is up for the long-distance breakaway?

One man who thinks so is Claudio Chiappucci. The eccentric Italian’s career was characterised by his attacking style and epic solo breaks during the 1990s. His memorable stage victory at Sestriere in 1992 came after he rode more than 100km solo across a saw-toothed stage profile over seven Alpine passes.

Isolation

“All I wanted was to isolate the big guys,” Chiappucci explains to Cycling Weekly 24 years later. “I wanted a hard race from the beginning. I monitored the situation behind with the time board, my manager told me to slow down and wait for the other guys at the back, but I said I want to go. I knew otherwise they would break me to pieces.”

Chiappucci knew his best chance of beating GC favourite Miguel Indurain was to attack him early and catch him off guard. But even his historic solo ride came about almost by accident — he was convinced other riders would eventually bridge over to him and join him. When they didn’t, his team urged him to slow down and wait.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

>>> Icons of cycling: Miguel Indurain’s Pinarello Espada

Yet Chiappucci remained defiant, convinced it was his best shot, and continued anyway. However, tactics like this, he says, are rarely seen today.

“There is a lack of instinct in racing now, and that’s why everything happens at the end of a race and there is nothing interesting before,” the 52-year-old says. “Racing is becoming boring.

“It’s very difficult to do attacks like my style today. Technology has gone so high at the moment,” he continues. “The element of surprise is very difficult now because the riders have much more information. They’ve got TV, they’ve got radio connection — very quickly they can know what the story is.”

Hitting the jackpot

While it’s rare to see successful solo breakaways like Chiappucci’s today, that doesn’t necessarily mean winning from a break is an extinct form of racing.

It’s worth noting the Italian rode in a time when the landscape of cycling was very different — a time when race radios were uncommon but EPO wasn’t (Chiappucci himself admitted using the drug before later retracting his statement).

A breakaway is still almost guaranteed to form in every race. While it’s almost always brought back, there’s clearly an attractive romance to winning from a breakaway. Part of the allure to riders is that the odds are so against them; most ordinary people know that when they play the lottery they will never win the jackpot, but they still buy a ticket just in case.

During 2012, the Danish rider Michael Mørkøv got in breakaways in almost every race he could. The now 30-year-old Katusha rider amassed 1,119 kilometres riding in breaks in the first half of the season alone, including in Paris-Roubaix and Milan-San Remo; then at the Tour de France that July he escaped on five stages, clocking up another 720km ahead of the peloton.

“Most times the odds are totally against you but of course you have to believe in it. You want to give it a shot, that’s why you are in the race,” he says.

Etixx-Quick Step’s Matteo Trentin agrees. The Italian has won stages at both the Tour de France and Tour of Britain after riding as part of a breakaway group all day, and admits success is down to pure pot luck.

“Only when I started sprinting at 100 metres to go [did I realise] the win was possible,” Trentin says of his 2013 Tour de France victory into Lyon from an 18-man break. “Before it was like a lottery.”

Publicity hunting

In fact, such is the attraction of a breakaway in the high-profile races, that the battle to get in one in the first place can actually be the toughest part for a rider.

“In the Classics it’s the biggest fight ever,” Mørkøv says. “People are killing each other to get in that break. Sometimes in Paris-Roubaix it takes almost three hours before the breakaway goes.”

In those races, many teams vie to get their riders up the road, but it’s not always because they believe they can survive and win the race that way. The lure of lucrative air time in front of the television cameras is vital to appease team sponsors, while young riders often do it to get themselves noticed on cycling’s biggest stage.

Even Mørkøv admits he wasn’t necessarily expecting success for the majority of his numerous 2012 breaks.

“Most of the time I went in the breakaway to get ahead of the race, because I wasn’t sure I could follow the favourites,” he says. “My tactic was to get in the break, get a few minutes ahead of the pack and be caught up by the favourites whenever they have split the bunch a bit. Especially in the Classics, it can be a very good tactic for an outsider.”

>>> Five things to do now the cobbled Classics are over

The break remains one of cycling’s biggest paradoxes: why do riders scrap and slog to get in a breakaway if they know it is all but doomed to fail?

The answer is that riders know there’s always that one chance — however remote it may be — that the day they are in the break could the one day it will survive to the end.

In 2011 Johan Van Summeren was that one guy who defied the odds, and with it claimed one of cycling’s most prestigious prizes: victory in Paris-Roubaix.

While the favourites were all tussling with each other he slipped away unnoticed with 79km remaining as part of a smaller group, before distancing them to ride into the Roubaix Velodrome to win solo.

>>> Do riders need a special bike to win Paris-Roubaix? Mathew Hayman didn’t

“You never know,” Mørkøv says. “Maybe a crash happens behind so they [the peloton] cannot chase you down, or you’re part of such a strong group that you can stick together to the finish.”

Luis Ocaña: Tour de France stage 11, 1971

One of the few riders who proved Eddy Merckx wasn’t invincible. Merckx was largely deemed unstoppable in 1971, having won two consecutive Tours and 15 stages, but the Spaniard got the better of him twice in four days.

He won stage eight solo after attacking on the final climb, before breaking away again on stage 11. Ocaña attacked on the slopes of the Col du Noyer in the Alps, en route to Orcières-Merlette, riding the final 60 kilometres solo.

He was so strong he won by an almost unheard of eight minutes and 42 seconds, and to add insult also took the yellow jersey off Merckx. “Today Ocaña tamed us all,” Merckx said.

Jacky Durand: Tour of Flanders, 1992

Then a fairly unknown French rider, Jacky Durand surprised the whole cycling world when he won his first Monument after spending 217 kilometres in a breakaway.

Durand admitted he wasn’t even targeting the win in the race but escaped after 43 kilometres with three others.

The peloton was maybe guilty of underestimating the group — at one point they were allowed a 24-minute advantage — and it was made to pay.

Durand distanced his final breakaway companion on the Bosberg climb with just over 10km to go, and soloed to the finish to win by 48 seconds. He became only the third-ever Frenchman to win the Tour of Flanders, and subsequent breakaway attacks became his signature style.

The information revolution

As Chiappucci points out, when you consider the amount of technology in modern racing it’s clear why so many breaks never go the distance.

Radios connect riders to their team cars, where directeur sportifs can access the race radio or stream live footage, while the motorbikes provide real-time splits to the riders. All of this makes monitoring a group up the road relatively easy according to experienced road captain Bernie Eisel.

“If we talk about flat stages, with a lot of effort you can bring every breakaway back,” he says. He even goes as far as to call days a group of four or five riders rides off up the road an “easy day”.

More often these days the break appears connected to the peloton by an invisible string, dangled out in front but never too far out of reach, ready to be pulled back when the time is right. The rule goes that for every 10-kilometres a group is ahead the peloton needs one minute to bring it back.

“You just bring them back as late as possible,” Eisel says. “If you bring them back at 100 metres to go you’ve miscalculated, but you still did it right.”

>>> My toughest day: Bernie Eisel

There’s also the fact that riders today are often given significantly less freedom by their teams to launch solo attacks and ride for themselves, as almost every team has a protected rider for every type of race.

“Most of the teams had a GC rider, or they have a sprinter that they believed in, and they wanted to save more or less everybody for the captain,” Mørkøv says of the 2012 Tour. “There weren’t too many riders who were just free to go.”

>>> Watch: On bike footage of Fabian Cancellara’s Paris-Roubaix crash

Maybe breakaway attempts are gallant, or maybe they are futile, but ultimately while there are riders still willing to roll the dice, place their bets, and chance their luck, probability says one will defy the odds and succeed, and with it give everyone else hope.

As Mørkøv says, while your chances of winning from a break at the start of a race can look difficult, you never know what can happen during the race. “You always have to have hope.”

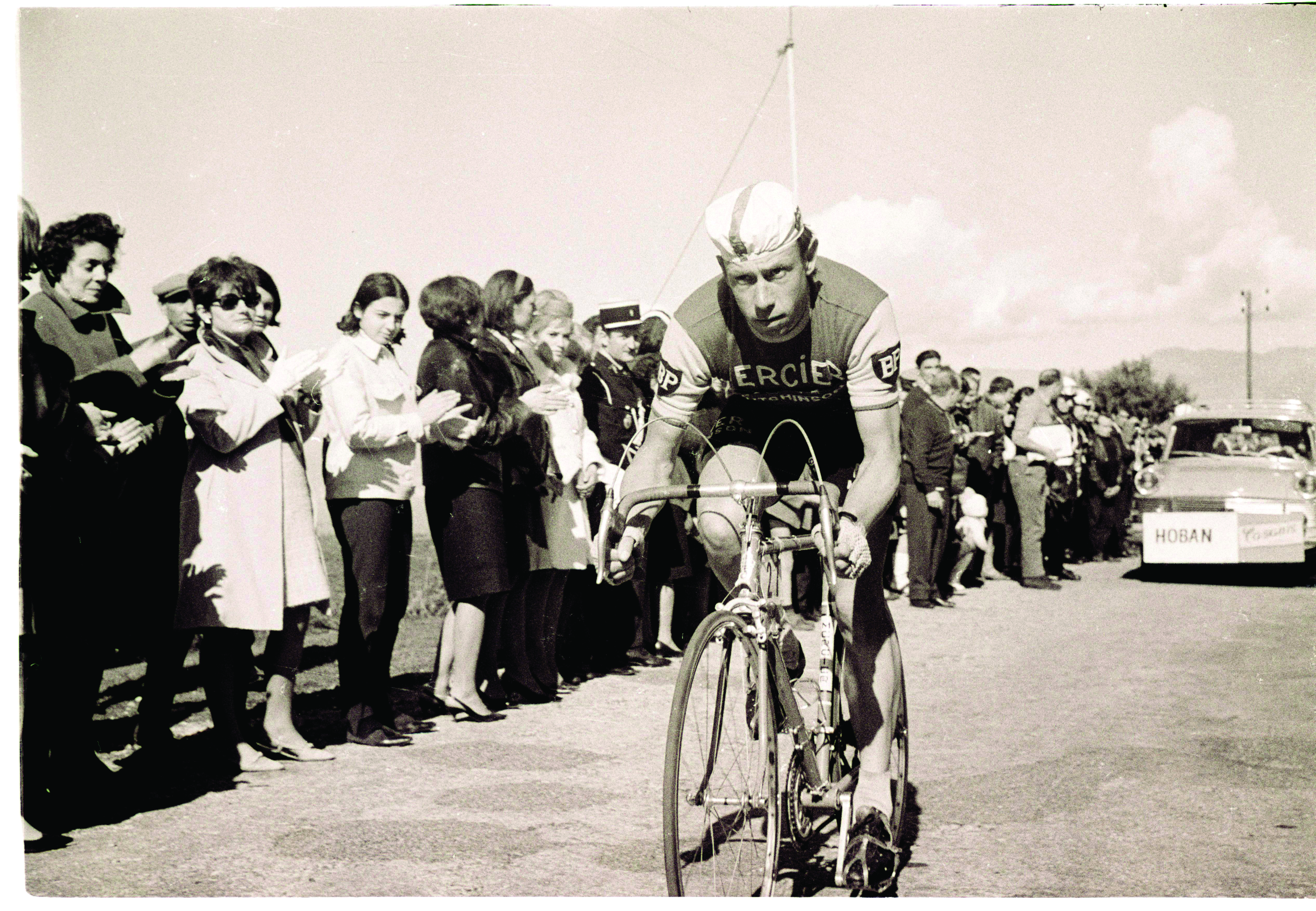

Tony Martin: Vuelta a España, stage six, 2013

As a time triallist, riding alone with only his own thoughts for company is something Tony Martin is used to. But on this day in the Vuelta a España, Martin had to survive what he later described as a “four-hour time trial”.

He planned to attack before the 175km stage, but thought other riders would go with him when he jumped clear in the opening kilometre — they didn’t. He carried on alone, stretching his lead to seven minutes, and held on all the way to the flamme rouge, before being caught 20 metres from the line.

And in a strange twist of fate, who was the rider who snatched the victory away from Martin? None other than Michael Mørkøv . “It was a very special breakaway that he made that day,” Mørkøv says. “I think he even made that break more special by getting caught.”

Jack Bauer: Tour de France, stage 14, 2014

Chances to win Tour de France stages don’t come often for domestiques like Jack Bauer.

On a flat stage targeted by the sprinters, few would have bet on Bauer and IAM Cycling’s Martin Elmiger making it as far as they did — almost the entire 220 kilometres.

But helped by a change in the wind and a late thunderous deluge, the duo held the bunch off and a glimmer of hope appeared as the kilometres fell.

Bauer held a bit of energy back to drop Elmiger inside the last kilometre, but sport knows nothing of fairytale endings and he was caught 25 metres from the line by the sprinters, where he then burst into tears.

Heroic, brave; history would remember Bauer, not the stage winner Alexander Kristoff. But that didn’t change things. “There’s definitely no pride,” Bauer said, “just bitter, bitter disappointment”.

Training drills to get you riding faster

Six steps to a successful breakaway

1 Look for a parcours that is particularly testing or technical in the first or last few kilometres of the race. “The harder the parcours is at the start, it could be 10 guys go and they are strong. To bring them back is pretty much impossible,” says Bernie Eisel. “A little bit left and right in the last 40km is also pretty hard to bring back, because the peloton doesn’t make up so much time.”

2 Prepare for changes in the weather — an unexpected tailwind or a rain shower and slippery roads can favour a small escape group.

3 Get in the right size breakaway. Too small a group and you could be easily overpowered; too big and it may be difficult for everyone to work together.

“Breakaway of six to eight guys is normally the best number, at least for a long stage,” says Michael Mørkøv. “Guys who have the courage just to try to see how far they can go, not be too smart.”

>>> Six amazing breakaways (videos)

4 Work with your breakaway companions to maximise your chances of survival. “The best way is those times where everybody has the same mind, like ‘come on let’s give it a shot today, let’s see if we can beat all the b******s behind’,” Mørkøv says.

5 Try to bluff to trick the other riders in the break you’re tired; then catch them off guard and attack. However, Matteo Trentin advises to proceed with caution here. “You have their car behind so you have to really blag the whole time,” he says. “The sports directeur will watch you and they will know that I’m fast [and faking].”

6 Watch out for the ‘classic’ breakaway stages in Grand Tours. They usually come after a string of tough mountainous days, on a hilly route — too difficult for the sprinters — when the general classification is fairly wrapped up. “It’s kind of in the air,” Mørkøv says. “For 70 per cent of the pack that is their only chance to fight for a stage win.”

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

-

Marianne Vos signs career-long 'forever' contract with Visma-Lease a Bike

Marianne Vos signs career-long 'forever' contract with Visma-Lease a BikeFormer world champion becomes team's second rider to pen indefinite deal

By Tom Davidson

-

British cycling legend Barry Hoban dies aged 85

British cycling legend Barry Hoban dies aged 85Eight-time Tour de France stage winner paved way for future British success

By Adam Becket