Seconds from disaster: how Garmin won the Tour's TTT

Team manager Jonathan Vaughters explains to Cycle Sport how Garmin-Cervélo won the Tour de France's team time trial.

Words by Edward Pickering

Pictures by Graham Watson

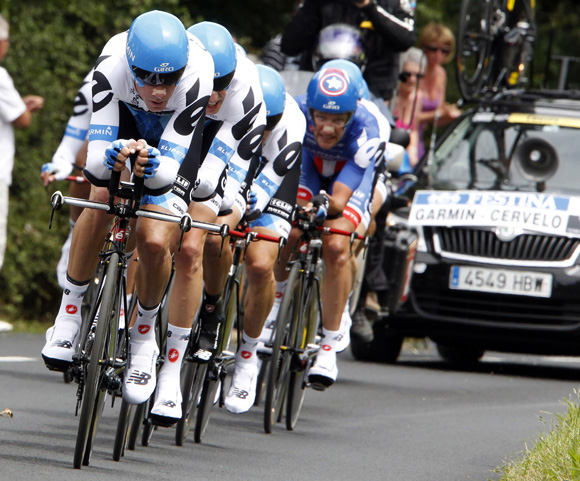

From a distance, the team time trial looks as smooth and predictable as the swinging of a pendulum. An unbroken line of riders, the first burrowing a hole in the air for the others to rush through in his wake, pulling off after his turn is done, then slipping backwards to join again at the rear. The image is similar to the impression gained from watching speed skaters gliding over ice. It’s hypnotic and relaxing to watch.

But actually, it’s nothing like that at all.

“What you need to know about the team time trial is that each and every one of the guys you see riding it are within about one per cent of completely falling to pieces at any one moment during the race,” Garmin-Cervélo manager Jonathan Vaughters tells Cycle Sport.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“From the outside it looks nice and comfortable, but when the guys are coming to the back, they’re barely catching the last wheel, every time. It’s always just about to fall apart.”

Look more closely, or watch from the roadside, and you can get more of a sense of what Vaughters is talking about. The riders are virtually sprinting at the front, punching through to the head of the line, taking themselves right up to, even slightly over, the redline, before pulling off. Pulling off is not easy – the riders have to recover from their effort, but maintain enough speed not to be dropped, and virtually sprint for the back wheel again, get up to speed and try to save as much energy as possible, while moving forward through the line and finding themselves on the front again. It’s far more aggressive than it looks – even though they’re not sprinting like at the end of a race, the process involves a very difficult combination of extremely hard riding and pace judgement. The standard is so high now that a single lapse will put a rider off the back, and once there, there is no chasing back on.

Garmin were the winners of the Tour’s TTT, a short, straightforward, almost out-and-back circuit starting and finishing in Les Essarts in the Vendée. The best teams finished astonishingly close together – BMC, Sky and Leopard-Trek separated by fractions of a second, four seconds back, and HTC-Highroad another second behind. RadioShack, at 10 seconds, and Rabobank, at 12 seconds, were not far off. Six teams lost half a second a kilometre or less to Garmin – the margins were incredibly tight.

In any fantasy cycling team line-up, you’d pick many of Garmin’s riders for your team time trial squad. But the victory was far more than just having the nine best riders. Vaughters insists that the level of detail in their planning, and its application, made the difference. That’s not to say that none of the other teams were applying a similar level of hard work to the team time trial, but Garmin had enough of an edge, in planning, organisation, riders and execution, to win.

The geek squad

Vaughters is a geek, and the team time trial rewards geekery. He’s also built one of the closest-knit teams in the WorldTour, and the team time trial rewards teamwork. He was at pains to point out before the Tour that seven of his nine riders had been involved in the Slipstream team project since it joined the top level in 2008.

The team time trial was where Vaughters planned for the team to win its long-awaited first stage win at the Tour, and he went about it properly. Along with the team’s aerodynamicist/sports scientist Robby Ketchell, the event was planned in both minute detail, and with an eye on the bigger picture.

In fact, according to Vaughters, the single biggest difference between Garmin and other teams is Ketchell.

Ketchell is the cleverest guy in the room. Vaughters tells Cycle Sport, “I would put my hand in the fire on this one. I can guarantee that Robby has produced more marginal gains in one person than Sky's entire marginal gains team has in many years. I’ve never met anybody as smart as him.”

Ketchell was working at the Fort Collins wind tunnel when Slipstream did their aerodynamics testing there in late 2007. Now he works full-time with the team. A former racer, Ketchell is a jack-of-all-trades. Crucially, he’s also a master at most of them.

“I have a background in computer science, engineering, mechanics and physiology,” he says. “I raced bikes from the age of 12, and did it my whole life, until I realised I’m more of a nerd than a talented bike racer.”

Ketchell’s approach is counter-intuitive – it is not to specialise. Instead, he tries to work in the overlap between all his areas of expertise to work out how best to apply them to cycling.

“Whenever anybody asks me what the number one factor is that contributes to performance, you can’t really put your finger on it. But you can say that it’s about the intersection of everything, how it all comes together and how you organise it,” he says.

And in the team time trial, he had the perfect pet project: “This was my Superbowl.”

The three Ts

The three major aspects of the planning were training, Tour selection and technique on the day. Obviously, there was more to it than just this. The mechanics had a lot of work to do, and the Tour wasn’t just about this one stage – the riders had to be prepared for 21 stages, not just the team time trial. But Garmin’s gains in the TTT were mainly focused around these three phases.

1) Training

“We only did a day and a half of specific training,” Vaughters says.

“Our guys have got a lot of experience, and what I learned from 2009 [the last Tour TTT] was that overdoing the specific training actually makes it worse.

“You have to have a plan, and riders who can understand and execute the plan. We made the team selection, we went to do a basic recon of the course, and then you do certain parts flat out.

“The aim in our preparation was to try and break the team. We tried to push them so far that riders would fall off the wheel, and the formation would break. We’d look at the mistakes and practice again, but the point was to ride hard enough to break the system, because then you can see where it breaks. Throw it on the floor, pick up the pieces, then see if you can put it together better.”

Once the team was used to riding together in formation, and all understood the capacity of the whole team, Vaughters backed off.

“My guys have done a lot of team time trials, and they’re experienced bike riders. If you overdo it, you start going worse again. You’ve got to let bike riders be bike riders. For the final three days before the Tour we didn’t touch the TT bikes.”

2) Tour selection

Garmin’s Tour team was based around supporting a strong challenge in the GC (this turned out to be Tom Danielson, but Ryder Hesjedal and Christian Vande Velde had also finished in the top 10 before), the anticipation of putting Thor Hushovd close to the yellow jersey in the first week (which was successful) and the TTT was key to both. There was also the unrelated, but equally significant challenge of supporting Tyler Farrar in the sprints, which also turned out well, with a well-executed stage win in Redon the day after the team time trial. In case that wasn’t enough, they left with the overall team prize as well.

For the team time trial, the squad was broken into sections. Five riders would be the “core”. The plan was for these five to be the only ones left at the end (the TTT’s time is taken from the fifth rider across the line): David Millar, Vande Velde, Hesjedal, Danielson and Hushovd. Two more – Ramunas Navardauskas and Julian Dean – were at the front for the opening kilometres, while Tyler Farrar and David Zabriskie were to work for the main body of the race.

3) Technique on the day

Ketchell’s planning for the day actually started the day the Tour route was announced, in November.

“Since November, I’ve been charting the wind patterns every single day. I looked at the last 20 years for the week of the TTT, and then within that time frame, I examined the minute data to figure out if that would help us make a small gain.

It reminds us of Team Sky’s failed attempt to outwit the weather in Rotterdam last year, but while that was about trying to guess when it would rain (very tricky in a maritime climate), Ketchell was more concerned about the wind.

“The weather was almost exactly how I expected it to be. The wind died down more in the afternoon than I had expected, but I knew it was going to. I knew it would be easier for the teams that went later.”

The wind on the day was very strong – cross-tailwind out, and cross-headwind back, and it did die down. But Ketchell didn’t just think about how the team would ride in the wind. He knew that it was important to try and set off as late as possible, which meant getting a good result in stage one, for the first three riders at least. The teams were sent off in reverse order of team GC after stage one.

“We thought about whether we needed to finish with our guys towards the back of the main group, or trying to get them all at the front, depending on what we thought the weather would be,” he says.

Also crucial: the order of riders on the line. Vaughters explains how the riders lined up at the start was dictated by their plan for the stage.

Remember that we described the course as “straightforward”? It mostly was, except for two technical sections with corners – one out of town straight after the start, and one coming back in, with the added complication that the final two kilometres were downhill.

“Our starting order was based on how we could do the first kilometre’s corners at the fastest speeds, with low risk, but nine riders doing it quickly,” says Vaughters.

“Look how we lined the guys up. The five guys who finished together were Millar, Ryder, Tom D, Christian and Thor. In front, we had Navardauskas and Julian Dean. Then behind, Tyler Farrar and David Zabriskie.

“I was always expecting the ends to fall off, and that the core would go on together.”

Cycle Sport expresses surprise that David Zabriskie, one of the best time triallists in the world, was not one of the core, but Vaughters felt that the best use of the American was outside the core.

“He wasn’t riding for GC, so we could could use him to cook his engine much harder far out on the course. Second, he doesn’t corner incredibly well, so with those final bends in the route, I wanted him to be done by the two k to go banner,” he explains.

There’s more.

“Through the start, Julian and Ramunas are good at cornering, so they got us out of town fast. Then David Millar sets the speed for the rest of the race. Why? Because he’s the fastest rider on the team.

“I put Ryder behind David. When David comes off, the team is going as fast as it is going to. So what’s Ryder’s job? He’s not as good at the TTT, so his job is to keep that same speed until the moment his rear wheel is in front of David’s front wheel. Whoosh, and then he’s off. Tom Danielson: the same. Just keep the speed up and off.

“Then Christian – he can do a longer turn than Ryder and Tom.

“Notice how I always put Tyler Farrar in front of David Zabriskie. David is one of our fastest guys, so when Farrar comes off the front, David is pulling, and we’re going very fast. What happens?”

Cycle Sport answers, “Tyler’s coming to the back of the line.”

Vaughters: “And given that the speed is very high with David on the front, what’s he going to have to do when the back rider comes past him?”

CS: “Sprint for the wheel.”

Vaughters: “And what kind of rider is Tyler?”

Bingo.

Trade secrets

Vaughters thinks that Garmin rode as close to the perfect race as the team could have done on the day. The margins were tight, although the dropping wind in the afternoon did make their time vulnerable.

“The big race of the day was between Sky and ourselves. By the time BMC and HTC went, the wind was a lot less strong,” he notes.

But there’s even more to the team time trial than all this. Vaughters makes CS switch off the Dictaphone when he explains a couple more things the team did, which were staggeringly simple, but turned out to be very effective. He doesn’t want all their TTT secrets out yet.

Vaughters has made a considerable investment in terms of building team spirit over the long term. And he reaction of the team to their first Tour stage win, in Vaughters’s favourite event, was diametrically opposed to the discipline and hard work that went into it.

“I basically screamed like a little girl when we won,” he says.

Afterword: foundations of a win

The team time trial had a minimal effect on the final general classification of the Tour – five riders who finished in the top 10 actually finished in the second half of the TTT, showing that a poor performance there wasn’t an impediment to doing well. At the same time, if the times for the event were stripped out of the final GC, the top 10 would still be in the same order, although Samuel Sanchez would only have finished four seconds behind Alberto Contador.

The main effect of the event was to negate Philippe Gilbert’s superiority in the uphill sprints and to put Thor Hushovd in yellow for the best part of a week. It also gave Cadel Evans important momentum – the Australian was in the top two both on the Mont des Alouettes and at Mûr de Bretagne, and BMC were second in the TTT. He gained insignificant time on his main rivals in these places, but looking back, the solidity of his challenge was built on the foundation of these early days.

Team Time gap Highest GC rider

1 Garmin-Cervélo - Tom Danielson (9th)

2 BMC 4sec Cadel Evans (first)

3 Sky 4sec Rigoberto Uran (24th)

4 Leopard-Trek 4sec Andy Schleck (second)

5 HTC-Highroad 5sec Peter Velits (19th)

6 RadioShack 10sec Haimar Zubeldia (16th)

7 Rabobank 12sec Robert Gesink (33rd)

8 Saxo Bank-Sungard 28sec Alberto Contador (5th)

9 Astana 32sec Rémy di Gregorio (39th)

10 Omega Pharma-Lotto 39sec Jelle Vanendert (20th)

11 FDJ 46sec Arnold Jeannesson (15th)

12 Europcar 50sec Thomas Voeckler (4th)

13 Ag2r La Mondiale 53 Jean-Christophe Peraud (10th)

14 Quick Step 56sec Kevin De Weert (13th)

15 Liquigas-Cannondale 57sec Ivan Basso (8th)

16 Saur-Sojasun 1-02 Jérôme Coppel (14th)

17 Lampre-ISD 1-04 Damiano Cunego (7th)

18 Katusha 1-04 Vladimir Gusev (23rd)

19 Movistar 1-09 David Arroyo (36th)

20 Vacansoleil 1-15 Rob Ruijgh (21st)

21 Cofidis 1-20 Rein Taaramae (12th)

22 Euskaltel-Euskadi 1-22 Samuel Sanchez (6th)

This article first appeared in Cycle Sport September 2011

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.

-

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much more

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much moreSupported It's not just Bontrager, Balfe's has a huge selection of discounted kit from the best cycling brands including Trek, Specialized, Giant and Castelli all with big reductions

By Paul Brett

-

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-Liège

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-LiègeUno-X Mobility to rebrand as 7-Eleven for Sunday's Monument to pay tribute to iconic American team from the 1980s

By Tom Thewlis

-

Jonathan Vaughters calls Bradley Wiggins' 2012 Tour win 'blemished, and that's painful'

Jonathan Vaughters calls Bradley Wiggins' 2012 Tour win 'blemished, and that's painful'The EF Education First team boss has also described the manner in which Dave Brailsford signed Wiggins to Team Sky as a "bully situation"

By Jonny Long

-

'Rigoberto Uran has a great chance of winning the Giro d'Italia'

'Rigoberto Uran has a great chance of winning the Giro d'Italia'Jonathan Vaughters believes his Cannondale leader Rigoberto Uran can challenge the likes of Vincenzo Nibali and Alejandro Valverde for the Giro d'Italia title

By Stuart Clarke

-

Lance Armstrong: the end

Resolution is fast approaching in the most controversial story in cycling. But there are still many questions to be answered

By Edward Pickering