Sperm behaves like a cycling peloton, claim scientists

Scientists show that sperm adopt peloton-like behavior for less resistance in adverse conditions

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As it turns out, our little swimmers are just like us, drafting off one another to encounter less resistance and save some energy for the, uhm, finish line.

It’s not too common for anything relating to the sport of cycling to move beyond endemic publications or industries unless, of course, when referencing any form of doping. But a recent article in the New Scientist relied on cycling terminology to explain the movement of sperm.

“Sperm move in packs like cyclists to push through thick vaginal fluid,” the article headlined, grabbing the attention of many a cyclist who were quick to pass it along with a chuckle.

For the science bit we’ve got the North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University to thank for this comparison.

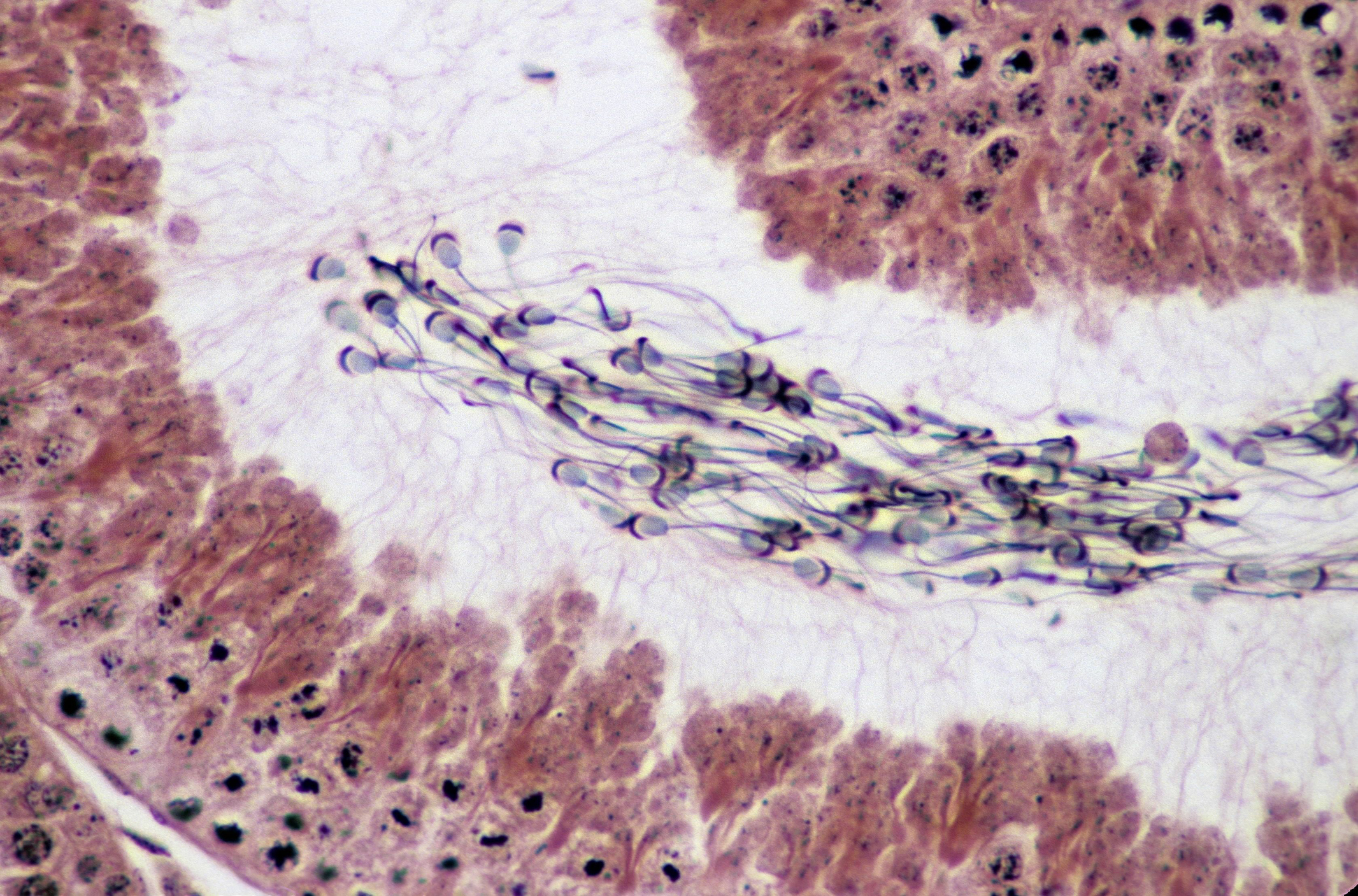

Until recently, we’ve commonly seen sperm portrayed as solo heroes, competing in an “everyman for themselves” race to the egg. However, these images are mere flat views of microscope slides and do not reflect their natural context, the article explains.

A three-dimensional portrayal tells a different story. Here, sperm appear to team up in clusters to help them swim upstream.

“In biology, when [cells and structures] do something, they should probably get something out of it,” says Chih-Kuan Tung at North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University. “So that became the question we were asking ourselves: what are these sperm getting out of it?”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

To find the answer, researchers crafted mock-ups of a cow’s reproductive tract and injected 100 million bull sperm —which resemble human sperm— into the tube containing a dense liquid to resemble the cervical and uterine mucus. A syringe pump was used to create different flow speeds.

Without flow, little pelotons of swimmers swam in a straighter, faster, line than individual sperm. And when the sperm enountered flow, and therefore resistance, the clustered sperm were able to swim upstream whereas the individual sperm could not.

Unlike cycling, however, there never appeared to be a protected sprinter. The clusters moved dynamically with sperm changing positions, falling off and catching back on.

“The arrangement resembles how cyclists ride together in a peloton so they encounter less air resistance,” the article states.

It’s this team work that allows the sperm to succeed and eventually reach the egg.

“Without this, maybe none of them actually could,” says Tung.

Beyond being a fun comparison to our beloved sport, these findings are meant to help diagnose unexplained infertility.

Sounds like a new avenue for cycling coaches…

Cycling Weekly's North American Editor, Anne-Marije Rook is old school. She holds a degree in journalism and started out as a newspaper reporter — in print! She can even be seen bringing a pen and notepad to the press conference.

Originally from the Netherlands, she grew up a bike commuter and didn't find bike racing until her early twenties when living in Seattle, Washington. Strengthened by the many miles spent darting around Seattle's hilly streets on a steel single speed, Rook's progression in the sport was a quick one. As she competed at the elite level, her journalism career followed, and soon, she became a full-time cycling journalist. She's now been a journalist for two decades, including 12 years in cycling.