The greatest cycling books of all time: 10-6

Continuing our countdown of the best cycling books ever written.

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: 50-41

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: 40-31

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: 30-21

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: 20-11

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: the top five

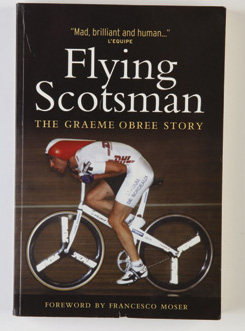

10. Flying Scotsman

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Graeme Obree, 2003

Profound, moving and at times tough-going account of a man driven but also held back by his depression. A hugely engaging and personal story that captivates you, even though you know how it turns out in the end. That Obree managed to write so openly about his personality is what allows it to transcend sport.

As the shop began to seem more and more lonely, I became more depressed and, even though I had my own business, I still felt detached from the world as though I had some invisible force-field around me that prevented me from being a part of it. Sometimes the world would seem so bleak and intolerable and I felt so depressed and isolated that I almost could not stand it. I had tried the ultimate form of escape and realise the distress caused to others. No, in those worst days, a bottle of vodka would make the world a different shade of black with maybe a hint of grey.

Graeme Obree, on writing Flying Scotsman

Writing the book was a cathartic experience. I wrote the whole thing out longhand. I didn’t have a computer but I wouldn’t have written it on a computer anyway. You think “Where’s the Z key?” and you’ve lost your flow. Also, because it was quite an intense experience I could take myself off and write anywhere, not be sat in one position at a computer. Some days it just flowed out of me and I’d write five or six thousand words without a break.

It wasn’t until I got to a certain point, maybe a quarter of the way in, that I thought: “Maybe I’m going to try to publish this.” The thing is, most sports books are sanitised and poppy, “I won this, I won this, I trained hard and I won this.” My choice was either to sell out and do that, or tell the whole story without leaving anything out. My decision was simple – it’s all staying in. There were things I couldn’t say for legal reasons but they were the only things that got cut out.

There was never any question of having a ghostwriter. This is a historical document if you want to analyse it. You can’t entrust it to someone else because any inaccuracy becomes a fact.

My depression was what drove me to achieve what I achieved and so my story is that of a holistic athlete. I was broke, I had no bike, and I was thinking of breaking the World Hour Record. It’s a story of a guy who’s not in the world of reality.

My publisher was the first person to read it. My writing was long hand, not terrribly neat, all on A4 pieces of paper with wee arrows where I was adding things on the back of the sheets of paper. Some lady at the publishers deciphered the whole thing and they phoned up to say it was great, which was a really good feeling. When you can hand someone a finished copy of the book with 90,000 words you’ve written in it, that’s a great feeling.

The first reviews in the papers were not good and I thought: “Oh no, what have I done?” I didn’t leave the house for a week, I just wanted to hide. Then I got a letter from someone who said: “I thought I was the only person on the planet who felt like this. Thank you for writing your story.” More letters started coming, from people who had relatives struggling with depression. One said: “My brother was suicidal and we just didn’t understand it.” People who hadn’t told their friends or family or even their doctors for fear that all they’d get was a ‘pull yourself together’ were writing to me.

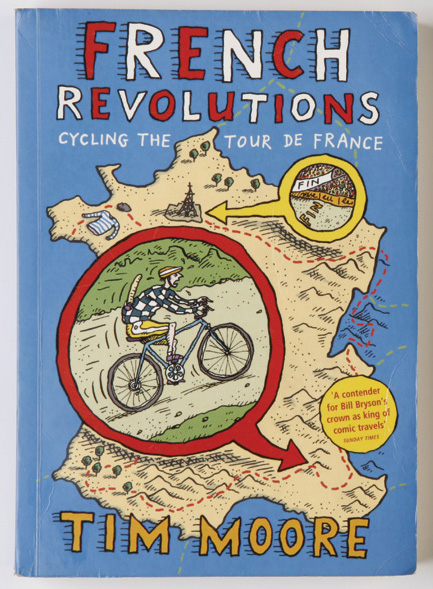

9. French Revolutions

Tim Moore, 2001

The cliché you see on the back of a million books – laugh-out-loud funny – has never been more apt. This book is not to be read over a cup of tea because you’ll end up spitting most of it out as you snort with laughter. Certainly the funniest cycling book you’ll ever read, this is Moore’s story of his attempt to ride the route of the Tour de France back before that itself was a cliché.

A quick pre-shower biological inventory was generally reassuring. The hamstring twinge was much better one I’d Boardmaned my leg up on the cistern, and I was particularly pleased with my Savlon-slathered perineum, which assuming – ooh! – that was it, emitted only the bruised sensation one might expect to feel a week after falling awkwardly at a tap factory.

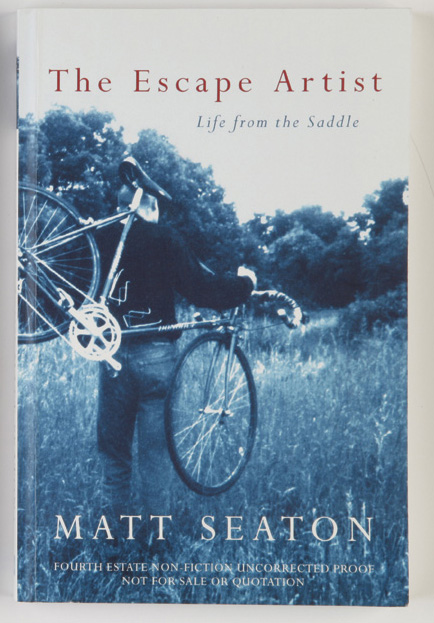

8. The Escape Artist

Matt Seaton, 2002

A deeply personal account of being an amateur cyclist, set against the backdrop of growing up in the 1980s and 1990s. There are no better descriptions anywhere of what it feels like and means to be a cyclist.

In a split second, you are round and free. You are still upright, and the road stretches out in front of you again. You cannot believe your luck, you are alive and intact. You feel the chill of the air as the wind slices through layers of clothing, greedily sucking away the body’s heat from damp undergarments and the scorching tears on your cheeks. But the cold does not hurt. You have taken flight.

Richard Williams on The Escape Artist

We pore over books about Fausto Coppi, Louison Bobet, Jacques Anquetil and Marco Pantani in order to wonder at the achievements of demi-gods, marvelling at the sacrifices made during the rise from humble surroundings and at the glory and suffering to be be found at the summit. Matt Seaton’s book approaches bike racing from a very different perspective, and one that most of us can come a little closer to sharing.

For those who cannot aspire to a kiss from a Tour de France podium girl, riding a bike has to take its place as a part of normal life. This is where The Escape Artist excels, in the way Seaton weaves together his love of cycling and the descriptions of his amateur racing career with the events of his young life, up to the death of his first wife, Ruth, from breast cancer.

Hence the title. While she was undergoing treatment, Ruth would tell him: “You need your exercise. It’s the only thing for you to do. It’s probably a good outlet.” It is both those things, exercise and outlet – a means of staying in touch with one’s younger self, and of achieving detachment from daily cares. It is also a way of testing one’s limits, of experiencing the satisfaction of going a little better than the day or weekend before -- or wondering what it means to be getting worse.

Seaton captures those feelings, and their infinite variations, with an eloquence heightened by the inevitable contrast with real suffering. And as he did a few years ago in his cycling column in Guardian, where he is now an online editor, he also dispenses bike lore with wit and wisdom: “The real reason cyclists shave their legs,” he concludes after a couple of pages of running through the standard explanations, “is very simple: it is because everybody does it.” A book to take out and read every year, with a rare blend of sadness and delight.

Richard Williams writes for the Guardian

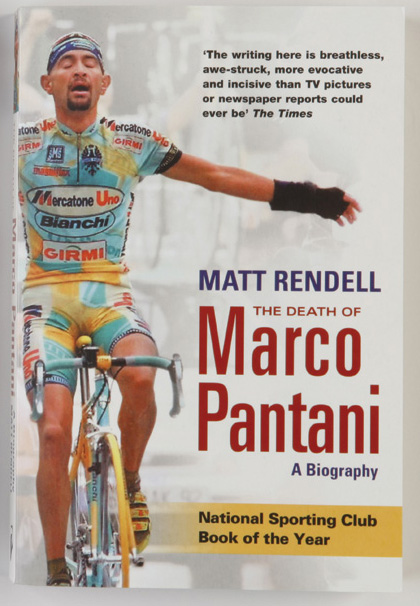

7. The Death of Marco Pantani

Matt Rendell, 2006

A forensic account of the life and death of Marco Pantani that leaves you with a terrible feeling of inevitability.

Marco’s humiliation at Madonna di Campiglio awoke in him a voice, a rant – “Look what they’ve done to me. Look what they’ve reduced me to” – that began to consume him. It would take him over for days and became a hindrance to living. In his cocaine delirium it began to fill books, paper scraps, even bed sheets. These jottings read like cries for help, or suicide notes written years in advance.

Matt Rendell, on writing The Death of Marco Pantani

I wrote a piece for Observer Sport Monthly and I spent four or five nights sleeping in the room under the one where Pantani was found while I went to speak to people who knew him, police, local journos and those who knew him. The door to his room was sealed up and no one was allowed up there but it freaked me out a bit. I was immersing myself in it. When you are working against the clock, that pressure compacts down into your subconscious a lot more intensely.

I couldn’t work out in my mind whether it was ethical to do the book. There had been stuff for the fans, by Ronchi, Bergonzi and others. Initially I proposed translating Ronchi’s book but Francine Brody, my brilliant editor, said: “Why don’t you write a biography?” I needed to earn a living, so that was it, really.

When I got out to Italy, I quickly realised there were a lot of parties fighting for control of his memory. And this freed me to take a position because there was already this unseemly fight going on. “He was this, he was that, he wasn’t the other,” everyone was fighting for his legacy. Then you realise you’re not the person wading in there asking upsetting questions of the family because it’s already going on.

Probably arrogantly, as writers, journalists, we think we can take a detached view. I think it’s true to say that I don’t judge anyone in the book. I don’t think that’s something that mortals can really do on other people. So I didn’t take a stance on whether he was right or wrong. I mean, one hit and run driver who leaves someone maimed on the side of the road has done something incomparably wrong to whatever Pantani did.

It was a stressful thing to research and write. I was having dreams and nightmares and nocturnal panic attacks about him. I saw pictures of him dead, which I really wish I hadn’t. I do know of an author who was seeking to get hold of them to publish them and that would have been completely unethical.

We sold our house in Essex and moved to Modena because I knew that if I didn’t go to Italy I wouldn’t be able to do a proper job. My wife left her job. It was a very big personal investment.

I have been accused of overdoing it and telling his life in too much detail but when you are writing a biography, it’s a massive moral commitment and responsibility and in the case of Pantani you couldn’t understand how far he’d fallen without understanding how high he’d climbed and how much he was loved.

The excitement of the movements he made, his accelerations and the style that doping made possible, you had to first be enthused about just how exiting it was to watch him before you could talk about the downfall. A good biography isn’t just about a person, it’s about the universe he lives in seen through that person.

Even from the age of 18 you realise he was a medical, scientific experiment. I became immensely angry with the idea that sport is media content. It shouldn’t be, it is people doing the best they can but it has become media content, advertising billboards and applied science.

People have said: “So, you’re not bothered by doping then?” Others think I am hard on doping and that I am glad Pantani died. I don’t really know what I think.

There’s only one reason a book should exist and that is that it is good writing. I actually think it stands and falls on that. There are some people who hate my style, others seem to love it, which is really flattering.

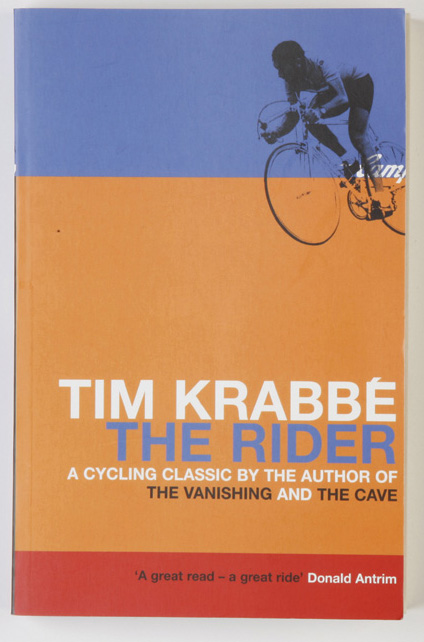

6. The Rider

Tim Krabbe, 1978

The only work of fiction in our top 50. Krabbe tells the story in the first person of the Tour du Mont Aigoual. Krabbe’s style is spare and minimalist, which makes it all the more impressive that the reader feels like he is part of the race.

Hot and overcast. I take my gear out of the car and put my bike together. Tourists and locals are watching from sidewalk cafes. Non-racers. The emptiness of those lives shocked me.

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: 50-41

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: 40-31

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: 30-21

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: 20-11

The greatest 50 cycling books of all time: the top five

This article first appeared in Cycle Sport December 2010

Follow us on Twitter:www. twitter.com/cyclesportmag

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.

-

I rode the full course of Liège-Bastogne-Liège and it opened my eyes to the beauty of this under-appreciated race

I rode the full course of Liège-Bastogne-Liège and it opened my eyes to the beauty of this under-appreciated raceFlanders and Roubaix have been and gone. Forget about them – some of the most epic racing of this Classics season is on the horizon

By James Shrubsall

-

Sunglasses brand 100% pledges to pay Giulio Ciccone's fine for throwing his shades

Sunglasses brand 100% pledges to pay Giulio Ciccone's fine for throwing his shades100% says "this one's on us" after Italian charged 250 Swiss Francs at Tour of the Alps

By Tom Davidson

-

Irish Continental level professional cyclist suspended after EPO positive

Irish Continental level professional cyclist suspended after EPO positiveJesse Ewart, who rode for Terengganu Cycling, has been banned until 2027

By Adam Becket

-

Convicted EPO doper Jarlinson Pantano returns to cycling with Colombian EPM team

Convicted EPO doper Jarlinson Pantano returns to cycling with Colombian EPM teamFormer Trek-Segafredo and IAM Cycling rider rejoins peloton after his four-year band expires

By Adam Becket

-

Filippo Ganna in no rush to extend his new Hour Record

Filippo Ganna in no rush to extend his new Hour RecordItalian says if he has a go at beating his own record, it will be before he retires, like Bradley Wiggins

By Adam Becket

-

How to watch Filippo Ganna's World Hour Record attempt: Live stream the event

How to watch Filippo Ganna's World Hour Record attempt: Live stream the eventHere's how to catch the Italian's long-awaited Hour Record attempt

By Cycling Weekly

-

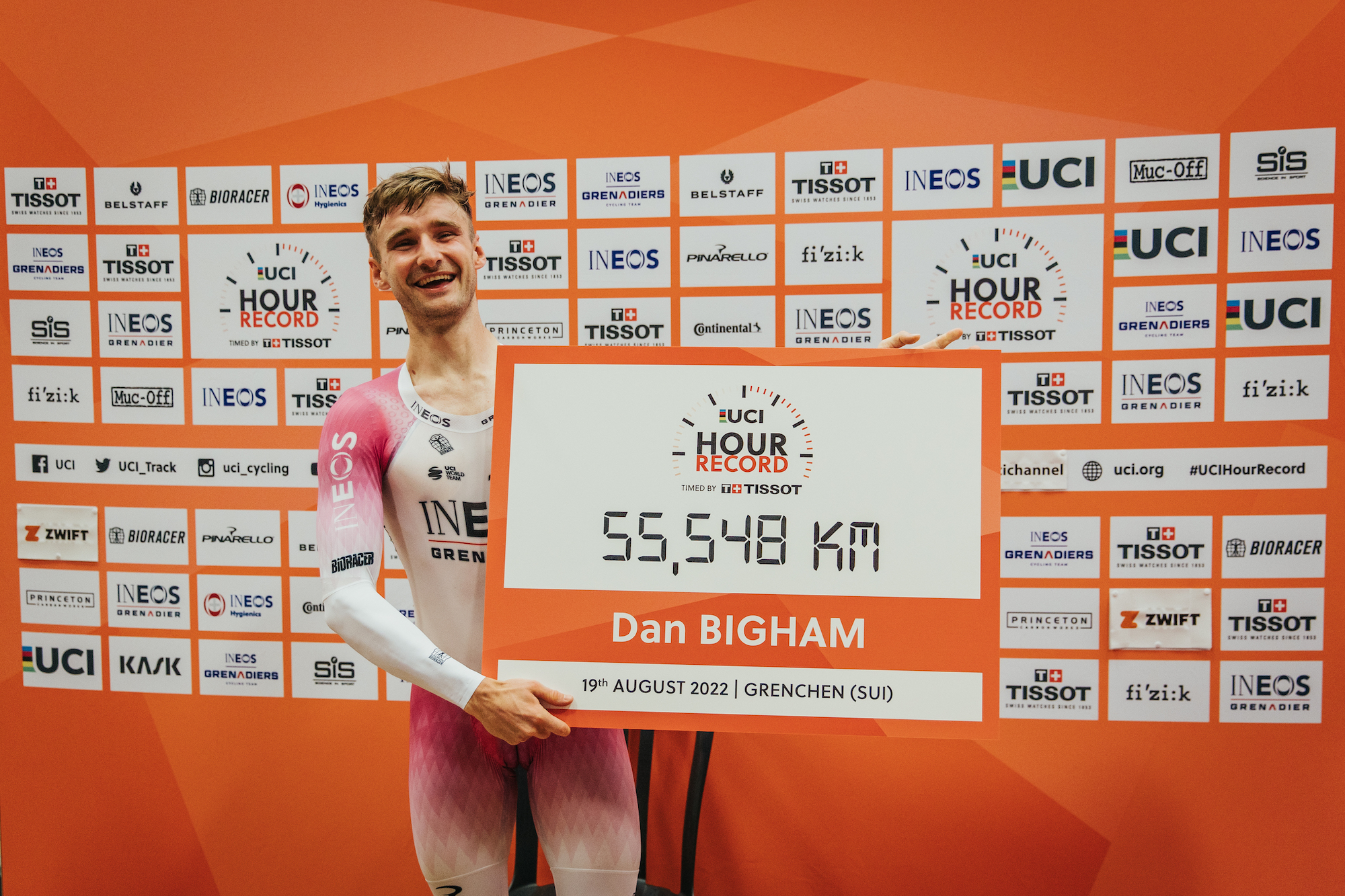

Filippo Ganna to attempt to break Hour Record in October

Filippo Ganna to attempt to break Hour Record in OctoberItalian will attempt to break 55.548km distance set by Dan Bigham

By Adam Becket

-

'It’s a bit mind blowing, pretty epic' - Dan Bigham on his Hour Record breaking ride

'It’s a bit mind blowing, pretty epic' - Dan Bigham on his Hour Record breaking rideBritish rider goes 55.548km to take record off Victor Campenaerts

By Adam Becket

-

Dan Bigham breaks Victor Campenaerts' Hour Record with 55.548km distance

Dan Bigham breaks Victor Campenaerts' Hour Record with 55.548km distanceEnglishman breaks the 55.089km record in Switzerland

By Adam Becket

-

Live stream: Dan Bigham's Hour Record attempt

Live stream: Dan Bigham's Hour Record attemptThe kit, the start time, the venue, and the magic number he needs to beat - 55.089km

By Adam Becket