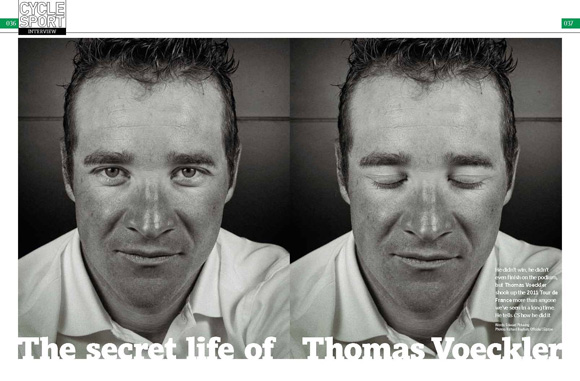

The secret life of Thomas Voeckler

In this revealing interview, the Frenchman explains how he rose to fourth in the Tour de France last year, and how he protects himself from his own fame and notoriety

Words by Edward Pickering, portraits by Richard Baybutt

Wednesday April 11, 2012. This article first appeared in Cycle Sport April 2012

For a few days last summer, Thomas Voeckler made us dream.

Through the first week of the Tour de France, he was a nagging, prodding, irritation to the bunch – attacking, probing, a bit of grit in the oyster. In the Massif Central, he somehow battled his way into the yellow jersey, which we assumed he would be borrowing until the first Pyrenean stage found him out. Instead, he matched the pace of the favourites through the mountains, and as Paris approached, people dared to entertain an impossible thought: could Voeckler win the Tour de France?

“Non,” Voeckler tells me now.

“I never once thought of overall victory. It was never an objective, and I was extremely clear in my own mind about that.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Voeckler pauses. “On reflection, perhaps that was a mistake,” he adds.

The dismantling of Voeckler’s defence of yellow started as the race entered the Alps. Seconds conceded on the downhill finishes into Gap and Pinerolo, where ragged descending betrayed the onset of fatigue, ballooned into minutes on the Alpe d’Huez stage following a disastrous tactical error. In the end, the combined willpower of a nation counted for nothing as Voeckler slipped off the podium, left with only fourth place and the fading memories.

***

To me, Thomas Voeckler epitomises everything that is exciting about bike racing, and I can’t help liking him. But that’s not to say that he likes me. He doesn’t dislike me either, I’m merely outside his sphere of concern.

Voeckler’s one of the most unusual characters I’ve ever interviewed. On one level, he is completely without ego and ambition. He turned down a reported 800,000 euros a year to ride for Cofidis a couple of years back, when Europcar were offering him 420,000, figuring that the family atmosphere and camaraderie which manager Jean-René Bernaudeau has built at the team was worth more than the extra 380,000 euros.

On the other hand, there’s something about him that seems to really get some people’s backs up. One prominent British rider once told me that Voeckler and his team were widely disrespected in the peloton for not doing their share of the work, for the Frenchman’s niggling attacking style. He’s portrayed, inaccurately, as publicity-hungry, a man whose ambition and media exposure is inversely proportionate to his talent as a rider, a kind of Richard Virenque for the 21st century, only without the climbers’ jerseys. Working out which of these two Thomas Voecklers is the true representation of the man is not easy.

But the most revealing comments about Voeckler won’t come from the man himself.

“Thomas is his own man,” Europcar manager Bernaudeau tells me. “He races, then he goes home to his family, and he protects that part of his life. That’s his priority.”

Voeckler is engaged in an invisible struggle, to keep his life at home as normal as possible while leading a double life as a national hero, sports star and media personality. Watching the Frenchman is as interesting as interviewing him, if only to contemplate the barriers he has built between himself and the world. Those barriers are what protect himself and his family from his success.

Before we talked, I had spent a couple of days just watching Voeckler kicking around the Europcar team’s hotel, a horribly bland Ibis on the dual carriageway out of town, the base for their pre-season training camp in Alicante. We’d set up the interview directly by text – unlike most modern cyclists, Voeckler doesn't feel the need to shoehorn a third party into interview negotiations – and he’d responded promptly every time, while we worked out the best time and place to meet.

He was polite and accommodating at every step. No problem, I thought. But if I was under the impression that would mean hanging around with him for the whole time I was there, I would have been mistaken. For our interview, he couldn’t have been more open, talking at length, honestly and eloquently about his incredible 2011 and his self-perception. He obliged photographer Richard patiently, posing outside in the chilly late afternoon sun. But for the rest of Cycle Sport’s time at the camp, apart from a brief hello and handshake on our arrival, we didn’t exist.

At breakfast or dinner-time, he’d walk straight by our table with neither a look nor a bonjour. As the team prepared to go out riding, and we mingled with the riders and management, he’d freewheel past us, sunglasses shielding his eyes, giving us as little attention as he might a roadside tree. The barrier was up.

***

2011 was when, for the first time, Voeckler’s results matched his ambitions. The wins started early, with a stage of the Tour of the Mediterranean, and continued through the Tour du Haut Var, Paris-Nice and the Four Days of Dunkirk, which he dominated with pugnacious verve, winning solo on the most difficult stage and taking the overall. He won a race a month until June, when circumstances reinvented him as a GC rider. He was 10th in the Dauphiné, then fourth in the Tour. Fourth in the Tour!

“I had 28 top 10s last year,” Voeckler says, and he’s miscounted, because we make it 32, compared to 13 in 2010. But the surprising thing is that according to Voeckler, nothing changed last year. He didn’t enter the season any fitter or more motivated than any other year, but he explains the liberating effects of momentum.

“My condition was good, and I won early. When you’ve done the work and you win, you know that your training must have worked. So I carried on winning – I had no doubt in myself,” he says.

“I was the same rider, but the circumstances were different.”

The clearest evidence of this came on two similar days a year apart: the final stage of Paris-Nice. In 2010, Voeckler was away with Amaël Moinard on the sweeping descent into the Promenade des Anglais on the sea front in Nice. With the bunch closing rapidly, Voeckler panicked and attacked the sprint early, giving Moinard the chance to close him down and pass him before the line. But a year later, Voeckler made good the error by attacking alone above Nice to win alone.

“It wasn’t a bike race, it was war,” he recalls. “Six degrees. Rain. Dangerous roads with climbs and descents. It wasn’t so much an attack getting away as the survivors contesting the stage. I was at the front, thought carefully about it, attacked and took some risks on the descent. Paradoxically, my biggest disappointment in 2010 was turned into an exploit a year later.”

It was Voeckler’s second stage win that week. He’d been trying since 2003 to win at France’s second most prestigious stage race and perversely, two victories came along at once. He describes the first stage win as a “deliverance”.

***

Voeckler’s heroics in last year’s Tour lit up the middle portion of the race, along with Thor Hushovd’s mountain stage wins, Cavendish’s sprint victories and the FDJ team’s relentless attacking. But Voeckler had suffered a less-than-ideal run-up to the race, in spite of the good form his Dauphiné had indicated.

His wife was pregnant, with the baby due on July 10, midway through the Tour. But the baby arrived early, on the Tuesday night before the race started in Voeckler’s home region of Vendée.

“I pulled an all-nighter on Tuesday, got to the team hotel on Wednesday, and went back to the hospital on Thursday and Friday. I didn’t ride for three days, and the Tour was a long way from my thoughts,” he says.

“It was lucky that the hotel was two kilometres from my house, and seven kilometres from the hospital. I took it all as a sign of destiny.”

The 2011 Tour was also a moment of destiny for Europcar. The team, set up as an amateur squad in 1991 by Jean-Réné Bernaudeau, was celebrating its 20th anniversary, and the Tour’s Grand Départ was to take place in Vendée, the team’s base. The team had flirted with disaster at the end of 2010, with Europcar parachuting in to sponsor the team at the 11th hour, after Bernaudeau’s search for a replacement for Bouygues Telecom faltered. The late rescue was too late to prevent several strong riders, like Pierrick Fedrigo, leaving, but the team survived.

It looked like the Tour would be a hard one for an all-rounder and attacker like Voeckler to prosper in. While there was much talk of the uphill finishes in the first week breaking the race up, the sprinters’ and uphill sprinters’ teams jealously controlled the bunch, shutting down the breaks on day after day.

Voeckler made a brave attempt on the stage to Cap Fréhel, whose twisting, uphill finish he reckoned might break up the pursuit. He escaped with Jérémy Roy in the final 30 kilometres, but he was caught with two kilometres to go. The next day, at Lisieux, he escaped with Jelle Vanendert in the final three kilometres, but was caught under the flamme rouge.

All that effort, for nothing.

But Voeckler feels that without these unsuccessful forays off the front, he would never have finished fourth in the Tour.

“If I’d won there, I might not have ridden with such conviction on the St Flour stage, which would have meant I didn’t get the yellow jersey,” he says.

“At Cap Fréhel, if Jérémy Roy had had the form he was showing at the start of the Tour, we’d have stayed away. But he’d already been in a few attacks by then, and he got tired. Even then, we still got close.

“But I was finding it easy to ride at the front. It showed how good my condition was – even if I had to drop back in the bunch, I could easily find my way to the front.”

***

In 2004, Voeckler famously got into a break which earned him the yellow jersey, and the admiration of the cycling world, as he doggedly defended his lead while Lance Armstrong casually ate into it.

Seven years later, the Tour smiled on Voeckler again, when a combination of luck and circumstances gave him a second stint in the yellow jersey. On the extremely hilly stage to St Flour, Voeckler had infiltrated the perfect break, packed with strong riders and proven Tour stage winners: Sandy Casar, Juan-Antonio Flecha, Luis-Leon Sanchez and Johnny Hoogerland. Crashes in the bunch led to a truce behind, while the break forged ahead. Then the break itself suffered from a one-in-a-million piece of bad luck when a France-Television car carelessly swerved into Hoogerland and Flecha, knocking them off.

Voeckler, who was on the front, turned, assessed the situation, then put his head down and carried on riding. He’d instantaneously weighed up the pros of forging on (the yellow jersey) with the cons of sitting up to wait for two riders who would likely be unable to continue to contribute to the escape.

Voeckler was the best-placed overall out of the three survivors of the break and would gain the most from them staying away. But this meant neither Sanchez nor Casar particularly needed to contribute – the stage win was guaranteed for one of them, but the other would finish the day with nothing but tired legs. There was no reason for either to work, the better to save themselves for the finish.

“I had to do the work. Sanchez sat on me and then won the stage, but he did the right thing, and I’d have done exactly the same in his situation,” Voeckler admits.

“I’d rather there had been only two of us – that way, one of us would take the stage, the other would take yellow, and we’d both work. Instead, I had to do everything. We’d have won by more if there had been just two of us.”

At St Flour, Voeckler was presented with the yellow jersey he’d last worn on July 20, 2004, and we all wondered if he’d hang onto it at Luz Ardiden, the first Pyrenean summit finish.

But if Voeckler was concerned about saving energy for that, he didn’t show it. He followed green jersey Philippe Gilbert as he attacked the very next day on a climb with 15 kilometres to go. For a brief period, we were treated to the glorious sight of the yellow and green jerseys on the attack together, even if the bunch reasserted itself by chasing them down. Even though he wasn’t getting the stage win he craved, Voeckler looked like he was having the time of his life. Again.

“I’d be lying to you if I told you I thought I was capable of following the best riders in the mountains,” Voeckler tells me.

Voeckler was contemplating the Pyrenees in the same way as he was in 2004: a serious obstacle, but one that could be surmounted, resulting in an extra couple of days in yellow. He still wasn’t thinking like a GC rider. He calculated whether the 2-26 he held over Cadel Evans, the best of the overall favourites, would be enough to carry the yellow jersey into the Alps. After all, in 2004, he’d had 9-35 over Lance Armstrong before the mountains, and he lost all but 22 seconds of that in two summit finishes.

“When I took the jersey, there were three days to the mountains – a rest day and two flat stages. No problem, my team was strong,” he says.

“Then there was the first Pyrenean stage. I knew I had good legs from the Dauphiné, the yellow jersey gave me motivation, I didn’t think it would be a problem. The second Pyrenean stage – long downhill to the finish, no problem,” he says, counting off the days on his fingers.

“For Plateau de Beille, on the morning of the stage, I felt that I would still be in yellow that evening, but not by much.

“That climb,” he adds with understatement, “was the surprise.

Thomas Voeckler had entered the Pyrenees as a lucky chancer looking to blag a few extra days in yellow. He left them as a serious dark horse for the Tour de France.

Even as he climbed with the favourites at Luz Ardiden and Plateau de Beille, Voeckler looked nothing like a GC contender. While he was riding faster than ever before, with increasing conviction every day, his characteristic puce-faced elbows-out style made him look like the odd man out among the thoroughbred climbers. But they couldn’t drop him.

“There was one moment on the Plateau de Beille when I suddenly realised what I was capable of,” Voeckler says.

“Andy Schleck attacked, and as the yellow jersey, it was my responsibility to chase him. I was pulling him back, slowly, and just got on to his wheel. I was on the point of cracking, thinking, ‘I can’t do this.’ And then he slowed. He was no better than me. From then on, I wasn’t afraid.”

Voeckler barely gave an inch in the Pyrenees. With the other favourites riding warily and defensively, we wondered if Voeckler could do the unthinkable.

But he’d stretched himself dangerously thin over the two weeks so far, and he was exposed on the two downhill finishes into Gap and Pinerolo.

“I wasn’t managing myself well,” he admits.

“I was making efforts at the wrong time. I actually wanted to take time on the descents, but I was overcooked. I didn’t adapt to the speed and braking, and ended up going off the road.”

And then, he reprised his heroic 2004 ride up Plateau de Beille on the Col du Galibier, clawing himself up to the finish through the cold, thin air to hang on to the yellow jersey by 15 seconds.

“At that moment, it became objective: podium. I wasn’t going to win – Evans was too strong in the time trial, but I could finish on the podium.”

Unfortunately, a terrible tactical error the next day, which finished at Alpe d’Huez, cost him that ambition. He made the mistake of following the reckless, although incredibly exciting, aggression of Andy Schleck and Contador on the Col du Télégraphe. Evans and Voeckler had been the only two riders to follow, with even Frank Schleck unable to hold the pace. But Evans had to slow, appearing to suffer a mechanical, while Voeckler pressed on.

“I was caught out – I thought Evans was in physical trouble. Just at the moment he was getting dropped, a television motorbike passed Contador and gave him a little draft, while I had to close a small gap around Evans. I was already at 99 per cent, and it meant I got gapped myself. I was 20 or 30 seconds behind them all the way to the top, but I was sure the race would have exploded behind me, so I continued to chase.

“I rode on my own. Four kilometres from the top of the Galibier, I turned around and saw an organised group coming up behind me, and at that moment, I realised I had made a big mistake,” he admits.

“It was an error of judgement on my part, but also the DS in the car, who had never been in that situation before and didn’t know what to do.”

Toward the top of the Galibier, Voeckler was caught by the group, which contained team-mates Pierre Rolland, Anthony Charteau and Cyril Gautier. Rolland, his eyes on the white jersey, was allowed to go on, while Charteau and Gautier paced the faltering Voeckler up. It was heartbreaking, watching the Frenchman crack and crumble, both physically and mentally. He weaved all over the road, and as Charteau set a pace that was too fast, yet necessary if Voeckler wasn’t to lose minutes, Voeckler’s head fell off.

He hurled a water bottle to the ground, its contents exploding over the road, and shouted so loudly at Charteau that his voice audibly cracked. He shouted in pure rage, like a child having a tantrum, at Charteau, but also at himself for having fooled himself into believing he could finish on the podium of the Tour.

“I cracked,” Voeckler says.

“Tony knows me extremely well. He knew that I’d cracked, and that it was up to him to sort me out. I was incapable of doing so. Normally, when I’m done, I’m done, but he got me moving. We rode together, and he kept on at me while I was yelling at him for going too fast.

“But my team-mates got me back. I was dead, and they were dead, but if they hadn’t been there, I’d have lost 10 minutes, not three. I was telling myself, save what you can for Alpe d’Huez,” he says.

“Up Alpe d’Huez I just focused on holding on to the top. I couldn’t follow the favourites, so I rode my own race. I didn’t even know that Pierre Rolland was up ahead winning the race. As I crossed the line, the assistant DS said to me, ‘Do you know who won the stage?’ and I was thinking, ‘What are you on about?’

“I couldn’t have given a shit who’d won the stage. I’d made a mistake, lost the jersey and blown the podium, and he was about to tell me it was Contador or somebody, which would have pissed me off even more.

“Then he told me it was Pierre, and that shut me up a bit. That was good.

“But at that moment, I have to be honest, my personal disappointment was greater than my happiness for Pierre. You can’t ever be happy at losing the yellow jersey.”

Voeckler’s story of the 2011 Tour is over. Except he’s got one thing to add.

“If I’d ridden the Alpe d’Huez stage how I’d ridden the Galibier stage, I would have been second in the Tour de France. I admit I’ve found it difficult to come to terms with that.”

***

My impression is that the most important thing for Voeckler is that his success on the bike doesn’t change him, that in spite being one of the most prominent athletes in the world for 10 days last July, he can still go home to his family and be the person that they know.

“It’s important that I stay how I am,” he tells me.

“I won’t change, even if my status has changed. How I am hasn’t changed. Only the way people see me has changed. I’ve come fourth in the Tour de France, but I’m not too important to push a vacuum cleaner round the house.”

Why is he this way? We discuss the three very different cultural environs of his growing up: Alsace, Martinique and Vendée, but he professes to be influenced by all three, yet typical of none of them.

“It’s just the way I am. I’ve always been cool – no big risks in life, no bling, no big dreams. I’m happy with my team – I could earn more money elsewhere, but what if I wasn’t happy?

Voeckler is cool, even cold, to the outside world. At the same time, from a distance, I see him laughing and joking with his team-mates at dinner, and his relationship with Jean-René Bernaudeau, who has been his mentor and manager for 15 years, is as much like father and son as coach and rider. I interviewed him on the rest day of the 2009 Tour de France, where what seemed like his entire extended family had descended on Martigny, in Switzerland, to be with him. We chatted, while Voeckler played with a baby in his lap, and various relatives poked fun at him. He was a different Voeckler to the one we saw at the Tour de France this year, and that most people see at races. But the constant attention from the media and cycling fans means that he has had to protect himself.

“People do think I’m stand-offish. One of the mechanics wanted to have a jersey, and he asked one of the managers to ask me, because he was scared of asking me himself,” Voeckler laughs.

“I’m not unapproachable. I’m not like that at all, really.”

But he is. He has to be.

Follow us on Twitter: www.twitter.com/cyclesportmag

www.twitter.com/edwardpickering

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Edward Pickering is a writer and journalist, editor of Pro Cycling and previous deputy editor of Cycle Sport. As well as contributing to Cycling Weekly, he has also written for the likes of the New York Times. His book, The Race Against Time, saw him shortlisted for Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards. A self-confessed 'fair weather cyclist', Pickering also enjoys running.

-

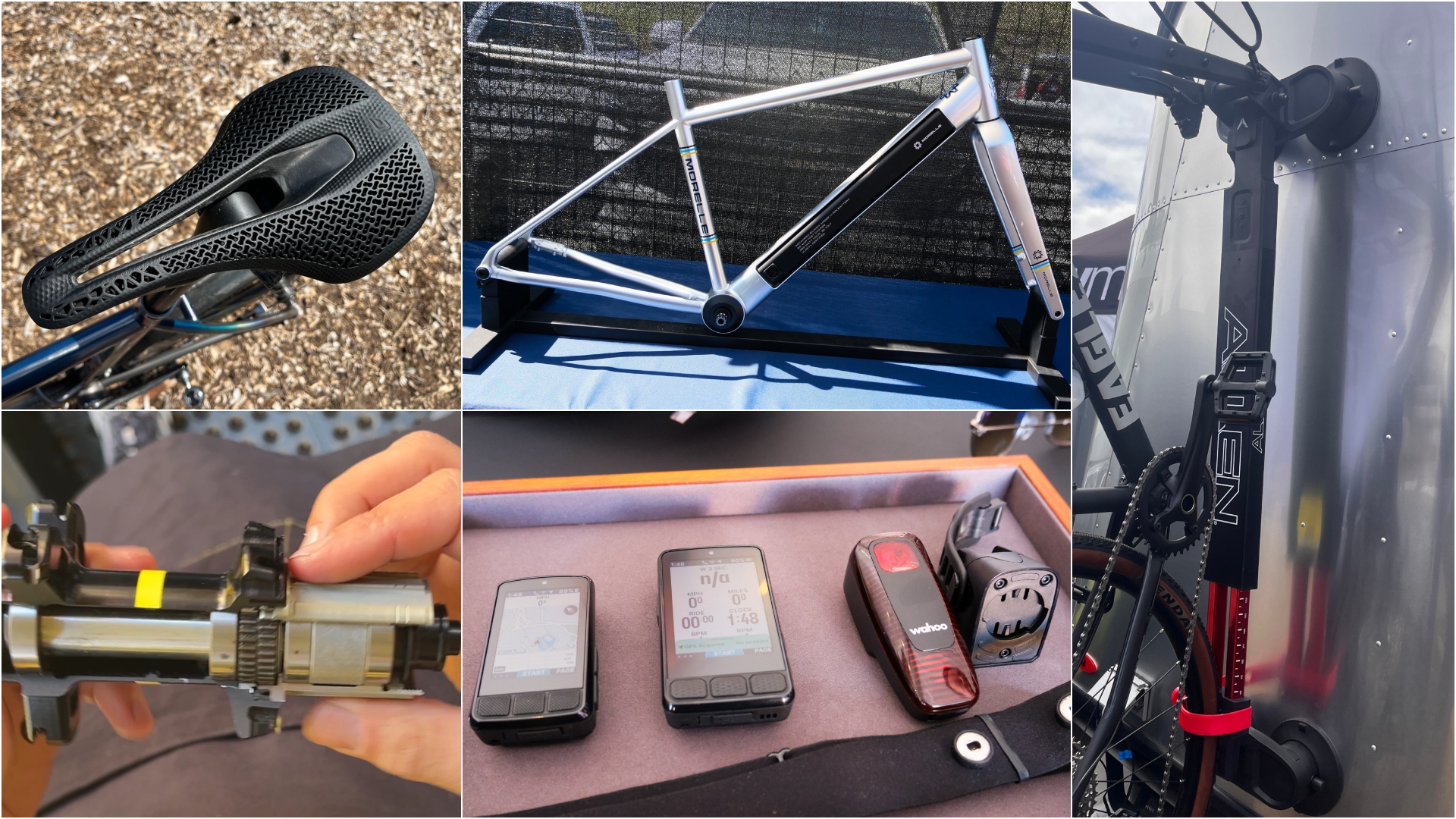

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2A few standout pieces of gear from North America's biggest bike gathering

By Anne-Marije Rook Published

-

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incident

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incidentCycling's authorities must do everything within their power to prevent spectators from assaulting riders

By Tom Thewlis Published

-

Tommy Voeckler fined after motorbike causes Jonas Vingegaard to stop at Tour de France

Tommy Voeckler fined after motorbike causes Jonas Vingegaard to stop at Tour de FranceFrance Télévisions pundit and driver fined 500 CHF and suspended for a stage for incident which saw Jumbo-Visma rider unclip

By Adam Becket Published

-

French pro Alexandre Geniez given four-month suspended sentence for domestic violence

French pro Alexandre Geniez given four-month suspended sentence for domestic violenceTotalEnergies rider had faced six-month sentence

By Adam Becket Published

-

'We want to be in tune with Peter Sagan to achieve great things together': Says TotalEnergies sports director on balancing Sagan and team identity

'We want to be in tune with Peter Sagan to achieve great things together': Says TotalEnergies sports director on balancing Sagan and team identityThe French team are keen to keep their own characteristics while also allowing the Slovakian to do his thing

By Tim Bonville-Ginn Published

-

Peter Sagan wants Niki Terpstra to continue at TotalEnergies rather than retire

Peter Sagan wants Niki Terpstra to continue at TotalEnergies rather than retireThe three-time world champion says he wants to talk to the two-time Monument winner if he wishes to continue riding

By Tim Bonville-Ginn Published

-

Peter Sagan: 'TotalEnergies not in the WorldTour is not a problem for me'

Peter Sagan: 'TotalEnergies not in the WorldTour is not a problem for me'The three-time world champion appears to be stepping down from WorldTour level next season

By Tim Bonville-Ginn Published

-

Peter Sagan will ride for Team TotalEnergies in 2022

Peter Sagan will ride for Team TotalEnergies in 2022The three-time world champion also brings riders and staff as well as new bike and clothing brands

By Tim Bonville-Ginn Published

-

Total Direct Energie change name and kit design after sponsor rebrand

Total Direct Energie change name and kit design after sponsor rebrandThe new design brings a bit of a tropical colour feel to the professional peloton in 2021

By Tim Bonville-Ginn Published

-

Britain’s Chris Lawless leaves Ineos Grenadiers to join Total Direct Energie

Britain’s Chris Lawless leaves Ineos Grenadiers to join Total Direct EnergieBritain’s Chris Lawless will be leaving Ineos Grenadiers after three seasons to join Total Direct Energie.

By Alex Ballinger Published