'They are still looking for the next Eddy, but they’ll never find one': Eight riders have been called 'The Next Merckx', but none have achieved as much

Heavy is the head that wears the crown of a comparison to cycling’s most revered rider – Chris Marshall-Bell gets the measure of what is simultaneously cycling’s greatest compliment and greatest curse

Edwig Van Hooydonck said it first. After winning the Tour of Flanders aged just 22 in 1989, the Belgian pleaded with the press. “Please don’t call me the new Merckx,” he cried.

Twenty-nine years later, it was the turn of Remco Evenepoel. After becoming junior time trial world champion, and capping off a truly outstanding junior career, the Belgian was defiant when facing the media. “Being described as the new Merckx is not something I want to hear,” he said. “Please, just stop it,” he later wrote on social media. “Nobody can be a new version of something he or she has never been and never will be. Stop comparing, please.”

Ever since Eddy Merckx retired in 1978, drawing to a close an unmatchable career of 525 wins, including victories in all the Grand Tours, Monuments and just about every track and road race he competed in, the cycling world – especially fans and pundits in Belgium – has been desperate to find the successor to ‘De Kannibaal’.

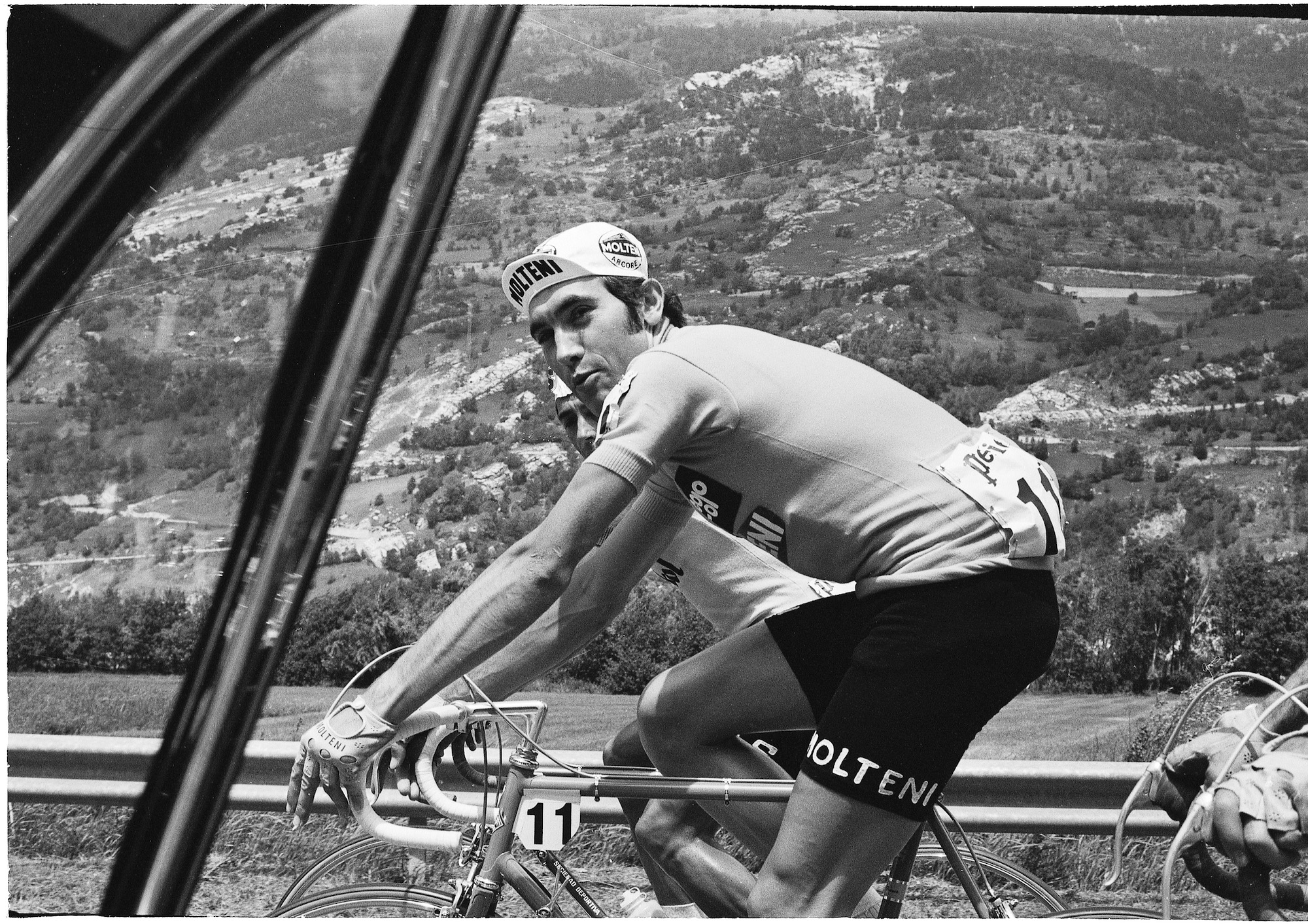

It was in 1979 when Alfons ‘Fons’ De Wolf and Daniel Willems were blessed – or was it jinxed? – by becoming the first two cyclists to be given the ‘new Merckx’ title. De Wolf was a slender, enigmatic rider, and sat beautifully on the bike. He was elegant, graceful, and had the talent to match. Willems, meanwhile, had time trial skills that the sport had rarely seen before, and his debut season was nothing short of outstanding.

But neither emulated or eclipsed Merckx – and no one probably will, so high is the bar the Belgian set. But that hasn’t stopped media, fans and even coaches and riders continuing to pronounce any rising star The Next Eddy Merckx. So what’s it like to wear that name tag? Is it a burden or a privilege? Is cycling’s greatest compliment a curse or a motivator?

Unwanted pressure

At the age of 20, Fons De Wolf felt that he was ready to turn professional. “Along with Daniel Willems, we were the best of our generation,” he tells Cycling Weekly. But Belgian Cycling issued a new rule in the summer of 1976 that prevented espoirs from signing professional contracts until they were 22. “We lost three years,” he says, ruefully.

In 1979, De Wolf finally became pro and he immediately made up for lost time, winning five stages and the points classification in his debut Grand Tour, the Vuelta a España. With Eddy Merckx having retired, Belgium was impatient for the Cannibal’s replacement. They turned to De Wolf and Willems.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“The press started it as soon as Eddy retired,” De Wolf says of being given the double-edged moniker. “Every journalist was talking about finding a new Eddy, but the pressure was too high for us.” It didn’t show at first. De Wolf won Il Lombardia and Milan-San Remo in successive years, and finished 11th at his first Tour de France. He also came close to winning Paris-Roubaix, the Tour of Flanders and Liège-Bastogne-Liège with stylish performances that emulated Merckx. Willems won 33 times in his first three years, including at several Classics: Scheldeprijs, De Brabantse Pijl and Flèche Wallonne, to name a few.”

Romance versus reality

It didn’t work out for De Wolf and Willems, yet the name continued to be recycled and shared out among various other riders (see boxout). In the mid-1990s, Frank Vandenbroucke emerged on the scene. “With his talent, Frank is the Cruyff of cycling,” Merckx said, cleverly comparing VDB, as he was known, with the footballer Johan Cruyff as opposed to himself. “He could win anything,” Merckx added.

Vandenbroucke never reached the levels he ought to have, but he had mimicked Merckx with his flamboyance. “We need heroes, examples,” the Belgian journalist Matthias Declercq wrote about Vandenbroucke. “People who don’t break, people who release us from our daily mediocrity. People who can fly, who do things we cannot.”

Was flair and panache all it took to echo Merckx? The romantics and poets might say so, but sport is a results business, and to really copy Merckx, a rider would have to win Grand Tours, Classics, rainbow jerseys, time trials, sprints, mountain tests, six-day track meets, set an Hour record, and everything in between for the best part of a decade. It’s as unfathomable as it is unfeasible. “They are still looking for the next Eddy, but they’ll never find one,” De Wolf says. “Just like they’ll never find the next Pelé in football.”

What has changed through the near half-a-century search is that even though Belgium now has two superstars in Evenepoel and Wout van Aert, riders who can win on a variety of terrain and regularly throughout the season, the country is no longer obsessed with finding the Belgian heir to Eddy Merckx. Since the turn of the millennium, non-Belgians have also been bestowed with the title.

But then in 1982 the wins started drying up and became less frequent for both De Wolf and Willems, and by 1984, Willems had retired and De Wolf would only claim two more victories in the subsequent six seasons. The Next Eddy Merckxes were no more – and they were battered in the media.

“Daniel and I never spoke about the name,” De Wolf says. “We were rivals, we were never close, but the press made it harder for us as we shared a name.

“Daniel was not smart enough to be the next Eddy. In my opinion, it was more difficult for him. He couldn’t handle the pressure, the noise, everyone having an opinion. He could never do it.”

What about De Wolf? “I finished second in the Superprestige rankings in 1980, just behind Bernard Hinault. That meant I was the second best bike rider in the world and I felt like I belonged there.

“But I didn’t like being favourite. I worked best as the underdog. When they didn’t talk about me, it gave me motivation to show people they were wrong not to think I could win. But when I was a big favourite, it was difficult.

“The press tried to put pressure on me, but I was clever enough to know I wasn’t as good as Eddy. I could do a few good races, two or three months a season at a high level, but not a whole year. I knew what I could and couldn’t do.”

Willems’s career flatlined early

At the end of 1981, De Wolf went to Guadeloupe and became ill. “I was never the same again.” He later found out that he had larva migrans, a parasitic disease where immature larval worms migrate around various parts of the body. It meant he was much more susceptible to getting ill. “Many people were saying I wasn’t good enough, I wasn’t doing a good job. They were laughing at me. It was very sad to go from 11th at the Tour to never again being in the top 10 in the world, but what could I do? Even though I didn’t know the exact reason at the time, I knew it was not my fault. Looking back now, I’m happy with my career.”

At the height of De Wolf’s success, fame found him. “It was strange,” he remembers. “I would go into a shop and everyone would know me. There were many requests from sponsors and even some people asking me to go into politics, but none of this interested me.

“I never spoke with Eddy about it all, but when my career wasn’t going so well, he said to me, ‘Fons, come with me. Your bike position isn’t good, let me change it, make you go faster.’ He is such a good guy, he always wanted the best for everyone.”

Enduring comparison

Tadej Pogacar wins Paris-Nice 2023

The latest one, alongside Evenepoel, is Slovenia’s Tadej Pogačar. At 25, he’s already won 63 races, two Tours de France, three different Monuments, and there’s even a chance he could challenge Merckx and Mark Cavendish for their all-time Tour de France stage win record.

“I have heard many times ‘this is the new Merckx’ without the condition being fulfilled, but with Tadej I think we are really there this time,” Merckx himself said in 2021, adding that Pogačar has “no weaknesses… [and] can do better than me in some races.” Pogačar has always rebuffed the suggestion, saying that “it’s impossible to win everything he has won”, but no modern-day cyclist looks like they could claim all five Monuments, the three Grand Tours, a world title and maybe set an Hour record like Pogačar could.

The original two, De Wolf and Willems, both claimed that the comparison to the greatest cyclist of all time held them back on occasions, so should it stop? “For me it’s not a problem. I understand it and it’s not important,” De Wolf says. “Everyone knows Eddy, Pelé and [Lionel] Messi, and that’s the reason people say these things.”

The comparison is an easy headline to write, an even easier one to make stick, and almost impossible to get rid of, whatever a rider’s results. “

Even today, when I am presented somewhere, they announce me as The Next Eddy,” De Wolf laughs. “People will always know me as The Next Eddy Merckx.”

The eight 'Next Merckxes'

FONS DE WOLF

Born: 1956

Nationality: Belgian

First crowned as The Next Merckx: 1979

Five Vuelta stage wins in his debut season as a pro, followed by victories at Milan-San Remo and Il Lombardia the following two years had him set for greatness. But illness thwarted him.

DANIEL WILLEMS

Born: 1956

Nationality: Belgium

First crowned as The Next Merckx: 197

Eleven victories as a neo-pro saw him hailed as Merckx’s successor, and all that before he had won six successive stages of the Tour de Suisse. But health problems cut short his career. He died in 2016.

CLAUDE CRIQUIELION

Born: 1957

Nationality: Belgian

First crowned as The Next Merckx: 1979

Described as having a French-speaking head but a Flemish heart, Criquielion won the Worlds, Tour of Flanders and twice won Flèche Wallonne. Grand Tour success eluded him, however.

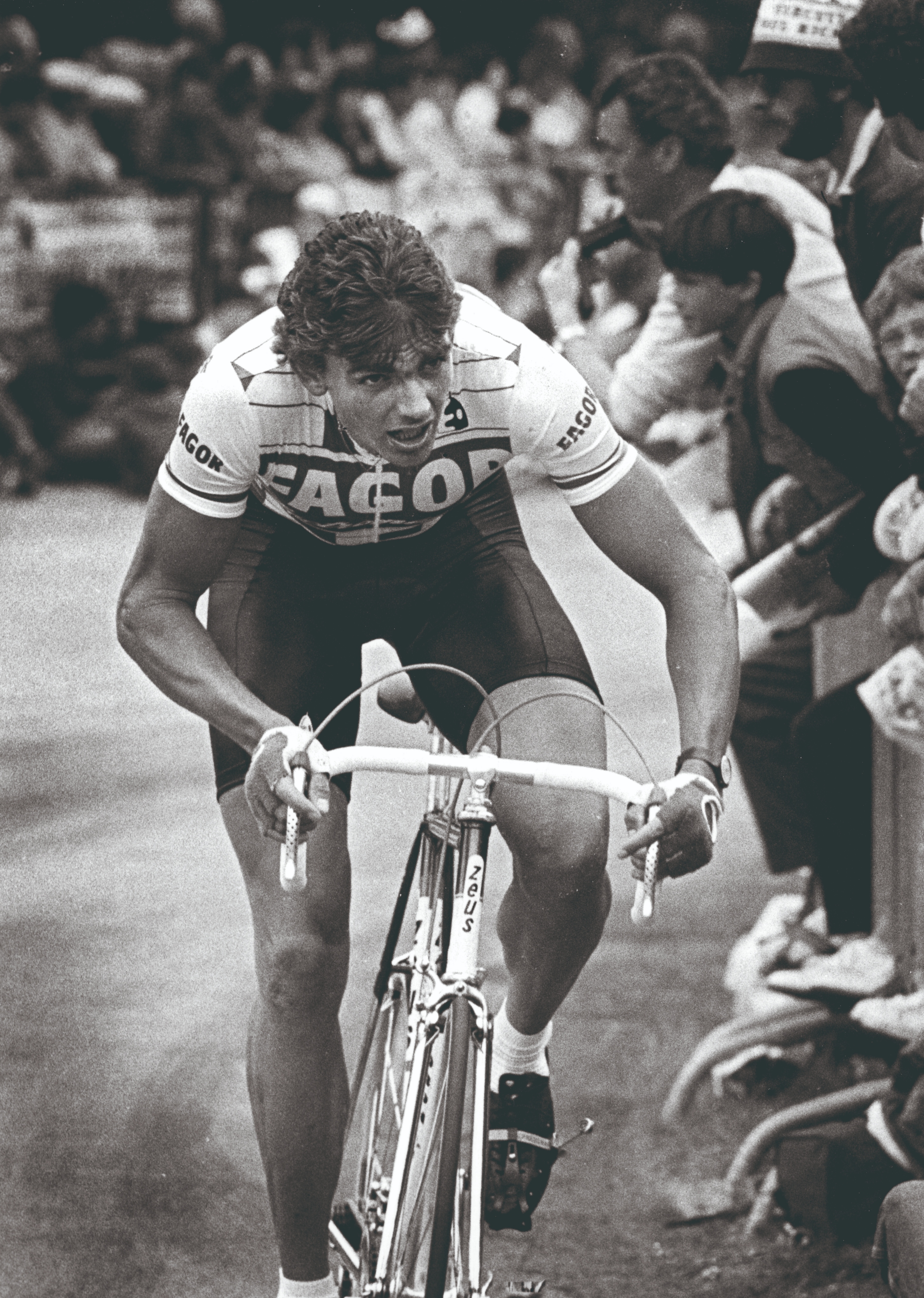

ERIC VANDERAERDEN

Born: 1962

Nationality: Belgian

First crowned as The Next Merckx: 1983

Vanderaerden’s 94 career victories included five Tour stages, as well as Paris-Roubaix, Tour of Flanders and Ghent-Wevelgem wins. He was arguably his generation’s best time triallist.

FRANK VANDENBROUCKE

Born: 1974

Nationality: Belgian

First crowned as The Next Merckx: 1996

Mercurial mega-talent Vandenbroucke had it all. Sadly he never fulfi lled his potential, a win at Liège-BastogneLiège his only Monument success. He tragically died in 2009, aged 34.

EDVALD BOASSONHAGEN

Born: 1987

Nationality: Norway

First crowned as The Next Merckx: 2009

At 22, Boasson Hagen had won more races than Merckx had at that age, with successes at Ghent-Wevelgem, the Giro d’Italia and the Tour, but the Norwegian’s career tailed off in 2013. He’s still racing.

REMCO EVENEPOEL

Born: 2000

Nationality: Belgian

First crowned as The Next Merckx: 2018

Evenepoel was being talked up as Merckx’s heir before he had signed a contract. In just five years, he’s been world champion, won the Vuelta a España, taken two victories at Liège-Bastogne-Liège and cemented himself as one of the sport’s biggest talents.

TADEJ POGAČAR

Born: 1998

Nationality: Slovenian

First crowned as The Next Merckx: 2020

A Tour win aged just 21 was followed by a second the year after. Pogačar is the undisputed best bike rider on the planet right now. Grand Tours, Monuments, Semi Classics, week-long stage races… is he actually The Next Eddy Merckx?

What’s it like being Eddy Merckx?

Belgium might have a monarchy, but there is no doubt that the real king of Belgium is not Philippe, the man who can legally wear a crown on his head, but Eddy Merckx. Wherever Merckx goes, there is a stream of people in his wake hoping to catch a glimpse, grab a selfie or get him to sign an autograph.

His long-time friend and former pro Rudy de Bie quips that, “There used to be a joke you’d hear all the time. It went like this: there was a stage of a bike race and the Pope was the special guest along with Merckx. Everyone present would ask, ‘Who’s that person next to Eddy?’”

Fons De Wolf occasionally goes to restaurants with Merckx. “When you go out with him, it’s not a normal life,” he says, “because everyone wants to speak with him. He will always sit with his back to the rest of the restaurant, and often we’ll ask for the table at the very end of the restaurant so people can’t see him. Eddy is a great person but it must be hard for him.”

Both De Wolf and De Bie are part of a select group of former professionals who still ride with Merckx most weeks. Also present on these star-studded rides are one-time Tour de France stage winner Jos Deschoenmaeker and former junior road race world champion Ronny Van Holen. Every ride – usually around 80km in length – starts and finishes at Merckx’s house, with the now 78-year-old hosting post-ride drinks afterwards.

Is he still the Cannibal? “Oh yes,” De Bie responds. “He’s still Eddy Merckx. He’s still got his Allen keys in his pocket, still changing his saddle height. He’s fit, strong, and enjoys riding the bike. We average 28 to 30kph every ride.”

De Wolf concurs: “When we go out on the bike, he still wants to be the best. It’s incredible. Eddy will never not want to be the greatest.”

Riding in the wheeltracks of Bradley Wiggins

The tag applied to promising British talent in the past decade has mostly been ‘The Next Bradley Wiggins’.

As Britain’s first Tour de France winner, Wiggins became a household name in 2012, and he admitted that “I felt like the most famous man in the country.” He secured his legacy with a fifth Olympic gold medal in 2016, and also held the Hour record for almost four years.

Though no Brit has emulated Wiggins’s diverse career – which included success on the track, in mountainous stage races and time trials – there is a new Wiggins in the men’s peloton, his 18-year-old son, Ben.

Wiggins junior will race for Hagens Berman Axeon-Jayco in 2024, widely regarded as the best U23 development team around. Explaining his decision to GCN earlier this year, Wiggins said that working with Axel Merckx – Eddy’s son who runs the team – was a major factor.

“With the dad he had growing up, he knew the pressures,” Wiggins said. “He’s been through it all and probably to a greater degree. I couldn’t think of anyone better to guide me through the pressures that come with my name.” Wiggins admitted that “no one can prepare you for the pressure and the noise” that comes with being the son of a cycling legend. “It’s only difficult to deal with with when it's not going well,” he added.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

A freelance sports journalist and podcaster, you'll mostly find Chris's byline attached to news scoops, profile interviews and long reads across a variety of different publications. He has been writing regularly for Cycling Weekly since 2013. In 2024 he released a seven-part podcast documentary, Ghost in the Machine, about motor doping in cycling.

Previously a ski, hiking and cycling guide in the Canadian Rockies and Spanish Pyrenees, he almost certainly holds the record for the most number of interviews conducted from snowy mountains. He lives in Valencia, Spain.

-

Remco Evenepoel hails end of 'dark period' and announces racing return

Remco Evenepoel hails end of 'dark period' and announces racing returnOlympic champion says comeback from training crash has been 'the hardest battle of my life so far'

By Tom Thewlis

-

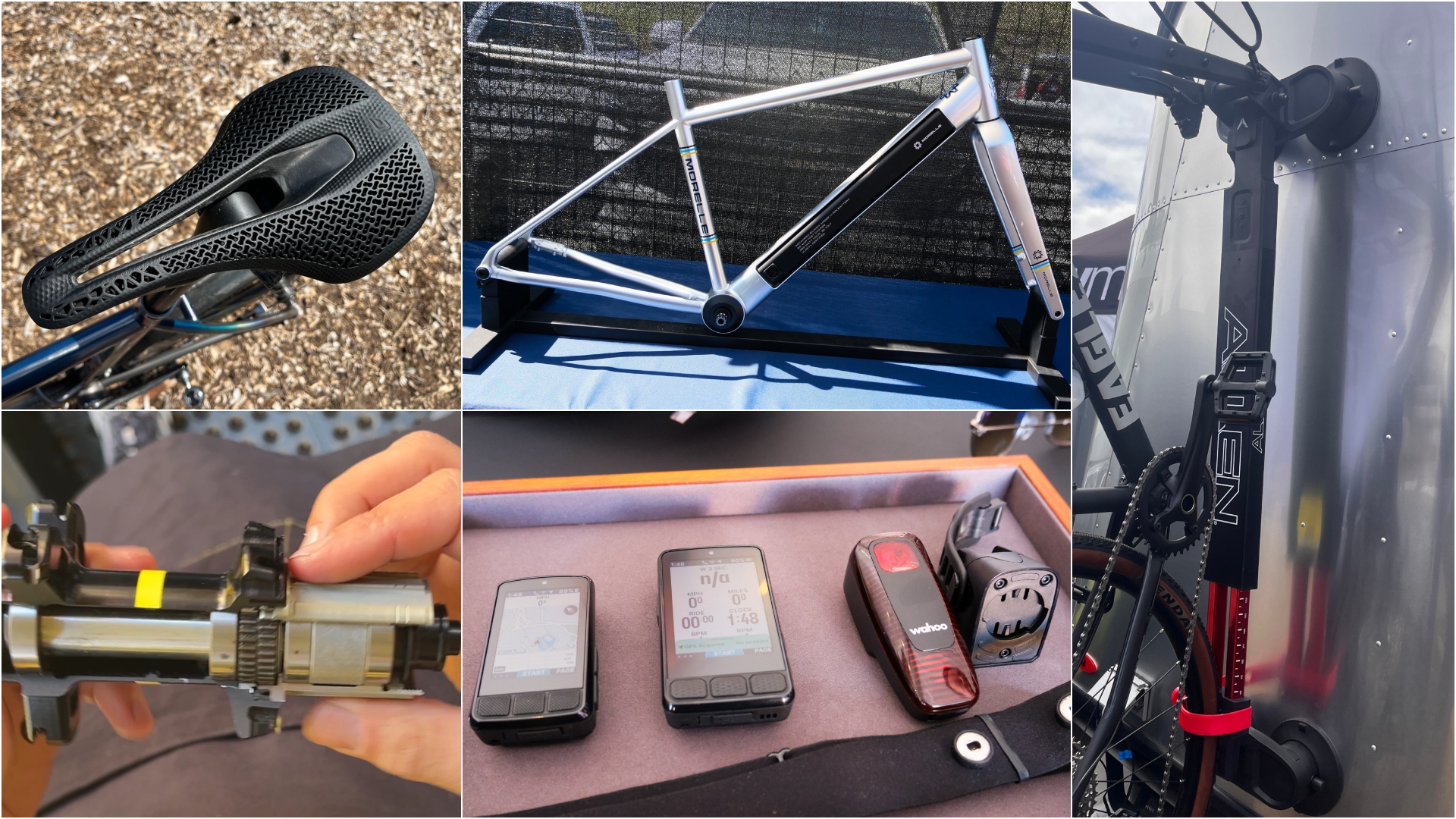

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2A few standout pieces of gear from North America's biggest bike gathering

By Anne-Marije Rook