'We're not trying to make the most bikes, we're trying to make the best bikes'

Carbon fibre bikes may rule the podiums, but steel and titanium still inspire devotion. What gives metal bikes their enduring appeal?

It's 29 years since Miguel Indurain won the Tour de France on his steel-framed Pinarello. Since then, road racing has been dominated by carbon fibre-framed machines. Despite this, nearly 30 years later, steel and titanium bikes are still objects of desire. We aren't talking here about the bikes of yesteryear that are celebrated with events such as L'Eroica.

There are still plenty of brand-new steel and titanium bikes being made with up-to-date groupsets, componentry and geometry. Indeed, Colnago's latest, limited-production steel bike, the Steelnovo, commanded a price tag of £15,000 and sold out all 70 units within two hours. Precious metal indeed.

Steel and titanium bikes have a revered place in some cyclists' hearts and are described in glowing terms, with words like 'classic' and 'timeless' often to the fore. Although some of the bigger brands do offer steel bikes, the kind we are talking about here is usually the preserve of smaller, boutique companies; machines created by craftsmen, not robots.

So, what is the enduring appeal of metal-framed bikes, when by most performance metrics, carbon is 'better'? Perhaps the most oft-touted answer is ride quality - that ethereal element which is difficult to describe but which gives a particular character to a bike.

Steel, and its posher cousin titanium, is frequently described as zingy, forgiving and comfortable.

It's a resilient industry because it's just people in sheds."

Sam Taylor, Stayer Cycles

It is seen as offering a more individual ride experience than the bland consistency of moulded carbon fibre, with each bike or frame having a discernible character. Indeed, John Wainwright, a pro with Raleigh-Weinmann in the 1980s, told me that although he was issued with two identical 753 steel-framed race bikes, he had a clear preference for the ride of one of the bikes, to the extent that the other languished unridden in his cellar for the whole season.

This idea of steel or titanium bikes having more 'soul' than carbon bikes is supported by the fact that they are the favoured materials of specialist frame builders such as Fairlight Cycles. That the end product is inexorably linked to the process and the craftsman adds a layer of romanticism that's missing from an off-the-peg carbon machine. Fairlight frame builder Dom Thomas summarises steel's appeal:

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"It is incredibly strong, yet you can build a frame with just fire and brass. It can also be very sculptural-parts are easily shaped and filed by hand. Of all frame materials, it is the closest to wood in the sense that the human hand can shape and refine it."

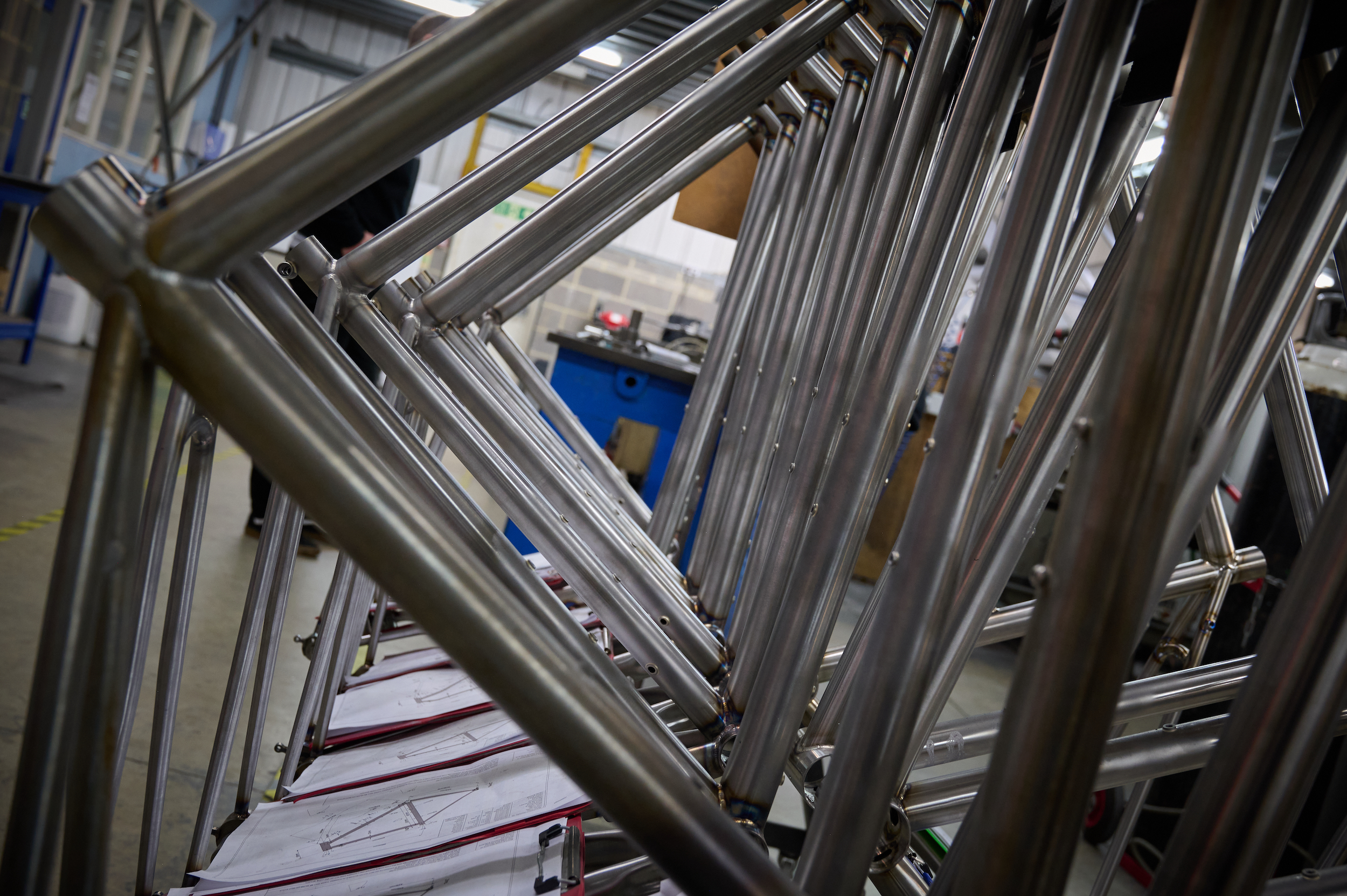

Stayer Cycles have adapted well to the industry ups and downs

Furthermore, many riders wanting or needing custom geometry end up with steel or titanium, as it is easier to produce one-off builds than it is with carbon-fibre.

Colour choice, mount placement and tubing type are also likely to be offered as discussion points by steel frame builders, involving more involvement in the process and a greater sense of emotional attachment than with an off-the-peg purchase.

Leytonstone-based Stayer Cycles's marketing blurb states: "Whatever speed you ride, a Stayer frame is made to last by folks who know bikes and how to put them together and are... the folks who you talk to when you get in touch to ask questions or to place an order."

Enigma are creating titanium works of art in their workshop

It's a real point of differentiation. Good luck trying to have a chat with the person who designed or built your Giant or Canyon. Durability is also frequently cited as a reason to choose metal. This has led to steel or titanium being popular choices for the best gravel and bikepacking bikes as well as road bikes, where perceived toughness is more relevant than low weight or aerodynamics.

As Thomas puts it, "If utility, function, longevity and repairability are at the top of a person's list, then steel cannot be beaten." Steel is preferred by long-distance tourers, not least because you're more likely to find a welder than a carbon expert in a remote corner of eastern Europe when a mechanical fault threatens to end your adventure.

Rob Quirk, of Quirk Cycles in East London, says that customers often get in touch wanting a 'forever bike', having ridden and been disappointed by mass-produced products. On a larger scale, carbon is seen as disposable, wasteful and more harmful to the environment.

Trek's 2023 report on the brand's sustainability calculated that, on a per kilo basis, manufacturing a carbon-fibre frame produced 24kgCO2eq (kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent) compared to just 1.77kgCO2eq for steel and 0.43kgCO2eq for recycled steel.

Tubing manufacturer Reynolds uses 100% recycled materials in its steel products, making it far more environmentally friendly than carbon. The scope for recycling carbon-fibre remains extremely limited.

Professor Tony Ryan, founding director of the Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures and stalwart of the Common Lane Occasionals Cycling Club says, "My favourite of all is my titanium gravel bike because it's so adaptable and so comfortable to ride. You get the lightness of carbon and the springiness of steel. Certainly, longevity and repairability are an advantage.

Pashley Cycles are growing their range once again

Without a doubt, my next road bike will be a titanium." There is an issue with the 'bike for life' concept, though. The cycling industry is very keen to constantly invent new standards and make older ideas obsolete.

It's all very well being perfectly happy with your 1995 Litespeed Vortex, 2004 Colnago C50 or even a carbon 2018 Cervélo R5, but if there are no rim-brake wheelsets, suitable cassettes or compatible bottom brackets, the bike becomes obsolete, whether you like it or not.

The last couple of years have been extremely tough for a lot of the bike industry, but the more boutique manufacturers have a business model that has been better able to weather the storm.

With shorter supply lines, smaller stock holdings and lower overheads, they can be far more agile than the bigger brands-or, as Sam Taylor of Stayer Cycles succinctly puts it, "It's a resilient industry because it's just people in sheds."

Dominic Mason adds, "We don't rely on mass manufacturing, and we can adjust orders based on exact demand." But all makers were until recently at the mercy of faltering groupset supply lines, as Glen Whittington of the Aeight Bike Company points out: "Now the market has settled down to a sustainable place, the majority of those who are left are doing it well and have a good customer base."

Much like restored and modified cars-so-called restomods - a modern steel bike still has familiar classic looks but with brakes and gears that work a lot better than the original concept.

There is also perhaps an acceptance among consumers that a few grams extra, or being slightly less aero, won't greatly impact their rides - whereas owning and riding a unique, beautifully crafted machine will add joy.

Mason Cycles in Sussex have made the most of the still growing gravel scene

Rides on a steel or titanium bike are not necessarily undertaken for PBs or KOMs, but simply for enjoyment's sake and taking pride in your discerning taste. Then again, don't underestimate the speed advantage just from being comfortable, especially on longer rides: "If you can make someone comfortable, they will almost always travel faster over longer distances, and they'll certainly have a more pleasant experience," says Whittington.

Cycling Weekly's Joe Baker wrote of his 1992 Columbus-tubed Massi Mega Team Race bike: "Pretty much every ride I do now will feature a cafe at some point, and the truth is I love how this looks up against the fence while I sip my coffee." Joe's thoughts are typical of steel bike buyers; it is a purchase made with the heart.

Like music lovers listening to vinyl or car enthusiasts choosing a wooden-chassis Morgan, the decision is driven not by stats or specs but by the feelings that the object induces. Thus, metrics like aero drag, weight and efficiency matter much less than that contented glance over your shoulder as you put the bike back in the garage after a ride.

By the same reasoning, a metal bike is less likely to be superseded the following season. If you want the fastest bike available, you constantly need to upgrade as new models come out, which is neither environmentally nor financially sustainable.

But if you own the nicest bike as judged by your own standards of taste, the love affair is likely to last much longer. As I pored over a titanium bike brand's websites and zoomed in on images of beautiful frames, I realised how different the message was compared to that of mainstream carbon brands.

Not once did I read about claimed drag figures or aerodynamic statistics, and there was barely a mention of weight or measurements of bottom bracket stiffness. Instead, the rhetoric was about spirit, feeling and the craftsmanship involved.

As Quirk Cycles puts it, "We're not trying to make the most bikes, we're trying to make the best bikes." There is also a tangible sense of community, with many of these smaller brands engendering strong brand loyalty.

Of course, bikes with metal frames aren't for everyone. Even the most ardent metal bike fan will concede that steel, and even titanium, cannot begin to compete with carbon-fibre in terms of weight or aerodynamics.

If you can make someone comfortable, they will almost always travel faster over longer distances

Glen Whittington

If outright speed and race-orientated performance are important to you, metal isn't for you. Sandy Smith of Sheffield's Fleur De Lys club says: "I've owned a titanium bike, and although it was nice enough, it never felt particularly sharp. I don't race, but my club rides feel pretty competitive, so I prefer the speed and low weight of my carbon bikes." With carbon frames under 700g available, sculpted in the most wind-cheating shapes, it is unlikely that a steel bike will ever win a professional race again.

Even Litespeed's self-proclaimed "world's lightest titanium road bike", the Coll dels Reis, has a frame that tips the scales at well over 900g. Another mark in favour of carbon bikes is that, while prohibitively expensive at the top end, they have never been more accessible at the lower end, with plenty to choose from in the £1,000-2,000 bracket. Producers of metal bikes aren't standing still, however.

Ribble's use of 3D printing for the frame of its titanium Allroad Ti bike shows that new technology and production ideas can be applied to the traditional as well as the modern. Rob Quirk also points out that modern steel alloys are a world apart from the steel tubing of yesteryear. In addition, titanium no longer seems prohibitively expensive, at least not when compared to premium carbon bikes.

The priciest Ribble Allroad Ti, with Shimano Dura-Ace, is £7,999, while a similarly equipped J. Laverack R J.ACK titanium bike is £8,995; it's hard to find a carbon bike as well-specced at those prices.

Given that the steel and titanium bike industry has survived and even thrived in the 29 years since 'Big Mig' powered his steel Pinarello to victory, it's reasonable to assume that the motorsport mantra of 'Win on a Sunday, sell on a Monday' does not apply here.

Instead, the market appears to be driven by a desire to own a bike that is more than just a tool and where the purchasing process is more involved than clicking the 'buy now' button.

Choosing steel or titanium is rarely an impulse purchase; it's a deliberate, often passionate decision driven by craftsmanship, heritage and the pleasure of owning something built to last. While every rider's motivation is unique, most are drawn to these bikes not just as machines to be pedalled, but as objects to be cherished, admired, and enjoyed for years to come.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Tim Russon is a writer and photographer who has worked in the outdoor and cycling industry for over 20 years. He can’t remember a time when he didn’t own a bike and has road, gravel, mountain and retro bikes in the shed. His favourite place to ride is the Dolomites, a simply stunning area which has breathtaking views and incredible roads combined with lovely food and great wine.

He prefers long, hot climbs in the big mountains, but as he lives on the edge of the Peak District he has to make do with short, cold climbs most of the time instead.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

-

Tadej Pogačar wins third Liège–Bastogne–Liège after 34 kilometre solo breakaway

Tadej Pogačar wins third Liège–Bastogne–Liège after 34 kilometre solo breakawaySlovenian launched a powerful seated acceleration on the Côte de la Redoute before riding away to victory

By Tom Thewlis

-

BESPOKED SHOW MANCHESTER: 11 highlights we loved from the show

BESPOKED SHOW MANCHESTER: 11 highlights we loved from the showIf you need a break from the stiffer, lighter, faster approach to bicycle design, head to Bespoked to check out the small-batch approach and soak up the good vibes

By Andy Carr

-

'I don't care about negative feedback' - The designer of the world's most outlandish bikes

'I don't care about negative feedback' - The designer of the world's most outlandish bikesVasili Zygouris takes inspiration from luxury motor cars in his futuristic bike designs

By Tom Davidson

-

Watch: YouTuber builds rideable bicycle out of 147 nuts

Watch: YouTuber builds rideable bicycle out of 147 nutsThe nut bike is fully rideable and offers endless modification possibilities

By Tom Davidson