Giant unveils 10th generation TCR - but could this be its last?

With the new frame claimed to be 4.2 watts faster than the 9th gen TCR, the gap to Giant's Propel aero bike is starting to become marginal

Twenty-eight years after the platform’s controversial debut for World Tour Team ONCE - as the first bike to feature a sloping top tube, which the UCI’s instinctively tried to ban - we are now on the 10th generation of TCR.

I've had the chance to spend 100km aboard the platform to bring you my first ride impressions. And, explain why this may well be the very last TCR.

Superficially, it might look like not much has changed - and for sure, it’s not a grand departure from the previous generation. But across the bike, there is a whole raft of details, updates and tweaks which are fascinating to get stuck into.

Before the minutiae, though, I’ll quickly address the two big questions looming over the TCR: what are the headline differences on this model? And where does the TCR now stand against the Propel aero bike - which shed a whole lot of weight in its 2022 update?

Starting with those headline changes, the most visibly obvious is the move to full internal routing, with the cables now running along the underside of the stem and down through the headtube. Regarding the performance, the 10th generation frameset is claimed to be 10% lighter, five watts faster and fractionally stiffer than the 9th generation.

But if you take the ‘total system efficiency’ into consideration, Giant says that the new TCR is as much as 12 watts faster than the previous model. That is a palpably big difference and a bold claim - I’ll break down what’s gone into this ‘total system efficiency’, and how it actually felt on a first ride, a little further on.

Coming back to the second of the big questions, ‘where does the TCR stand in the range?’ Andrew Jukaitis, Giant’s PR senior global product marketing manager, is clear that “[the] Propel is [Giant’s] premier aero road race product, but when it comes to the ultimate in stiffness to weight and adding aerodynamics, TCR is the new sheriff in town.”

The Giant Propel aero bike

But the differences have certainly narrowed. At this point the new TCR is 155 grams lighter than the Propel and five watts slower. It’s hard to imagine what the distinction would be between the next generations of each platform - and Jukaitis candidly admits this: “the question that we are looking for in the three to five year plan for both those products is when do the two combine…?”

So, without any further ado let’s jump into the details on what might be the last TCR as we currently know it.

The frame

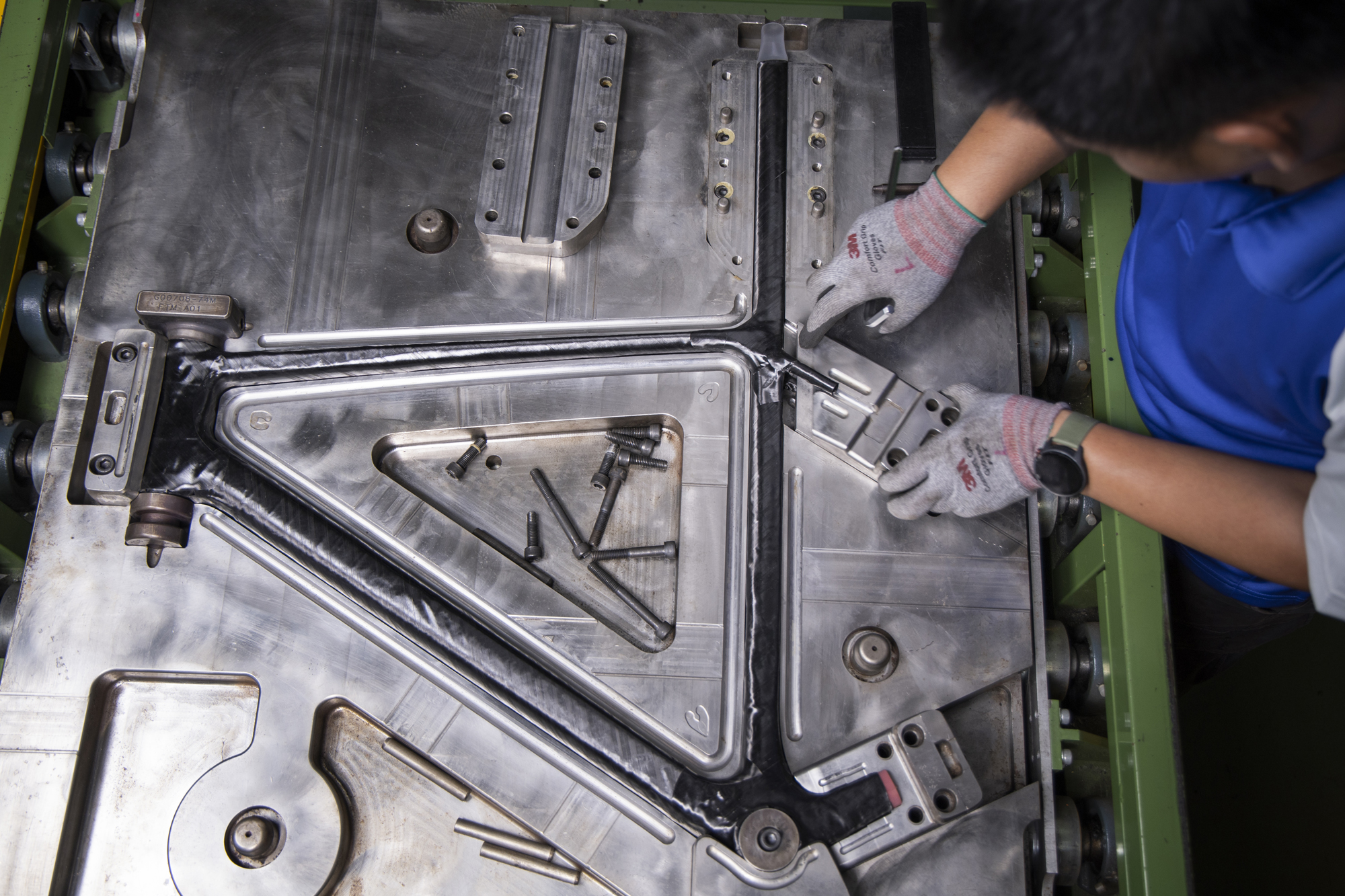

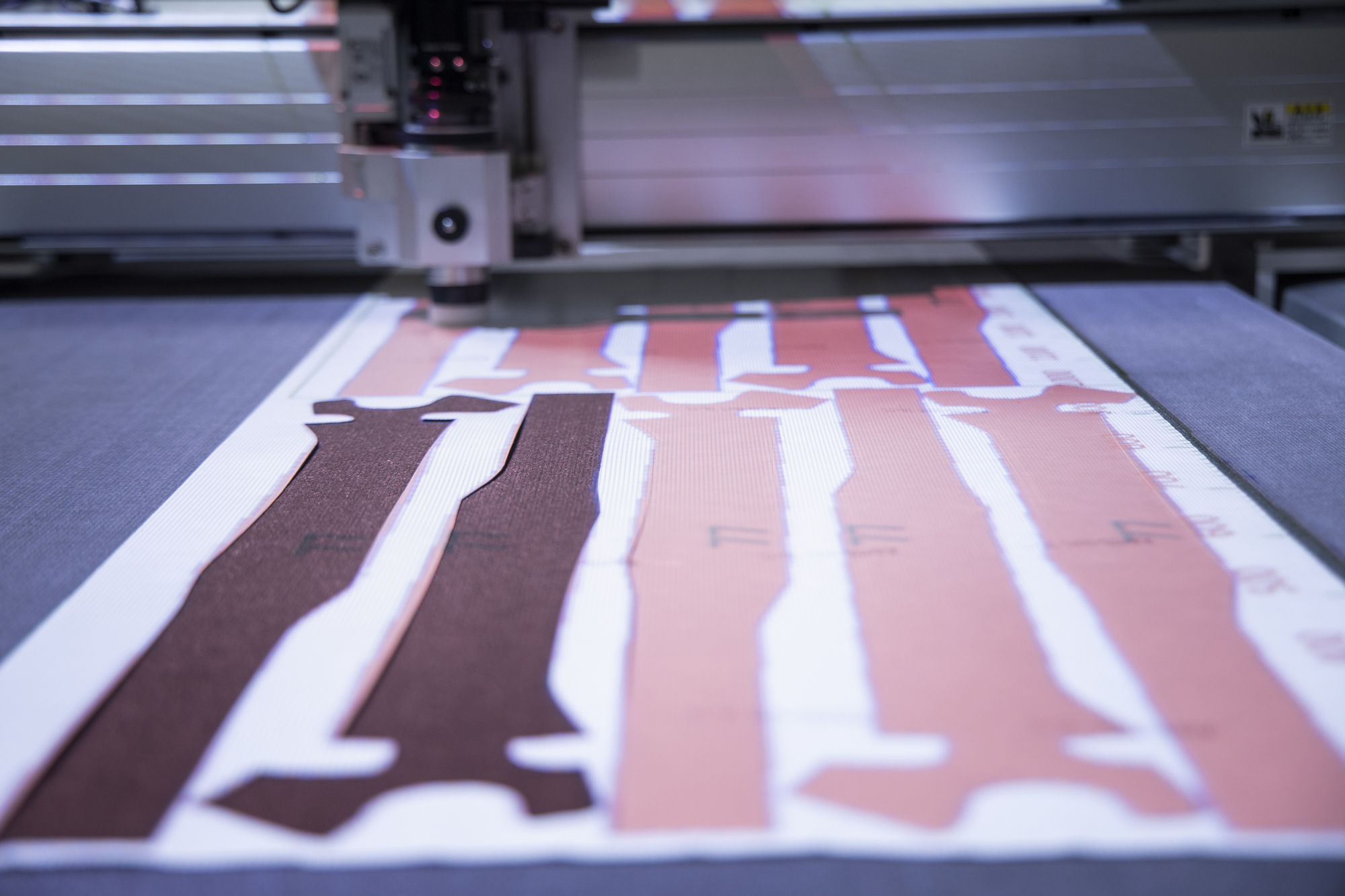

Giant - a brand which stands apart from most bike brands, in that it owns its own factories - has introduced two new technologies to its 10th generation TCR. The first is a switch from laser cutting for the carbon sheets to ‘cold blade’ cutting. This is more precise and eliminates the risk of deformation due to excess heat, allowing for fewer pieces of carbon to be used - which in turn helps Giant achieve the combination of a lower weight and higher stiffness.

Second, is that Giant can now make the front triangle out of one single piece of carbon, thanks to its use of a single bladder within the mould (the previous generation used three). This has eliminated the joins between the carbon tubes, again helping Giant to achieve its weight and stiffness targets.

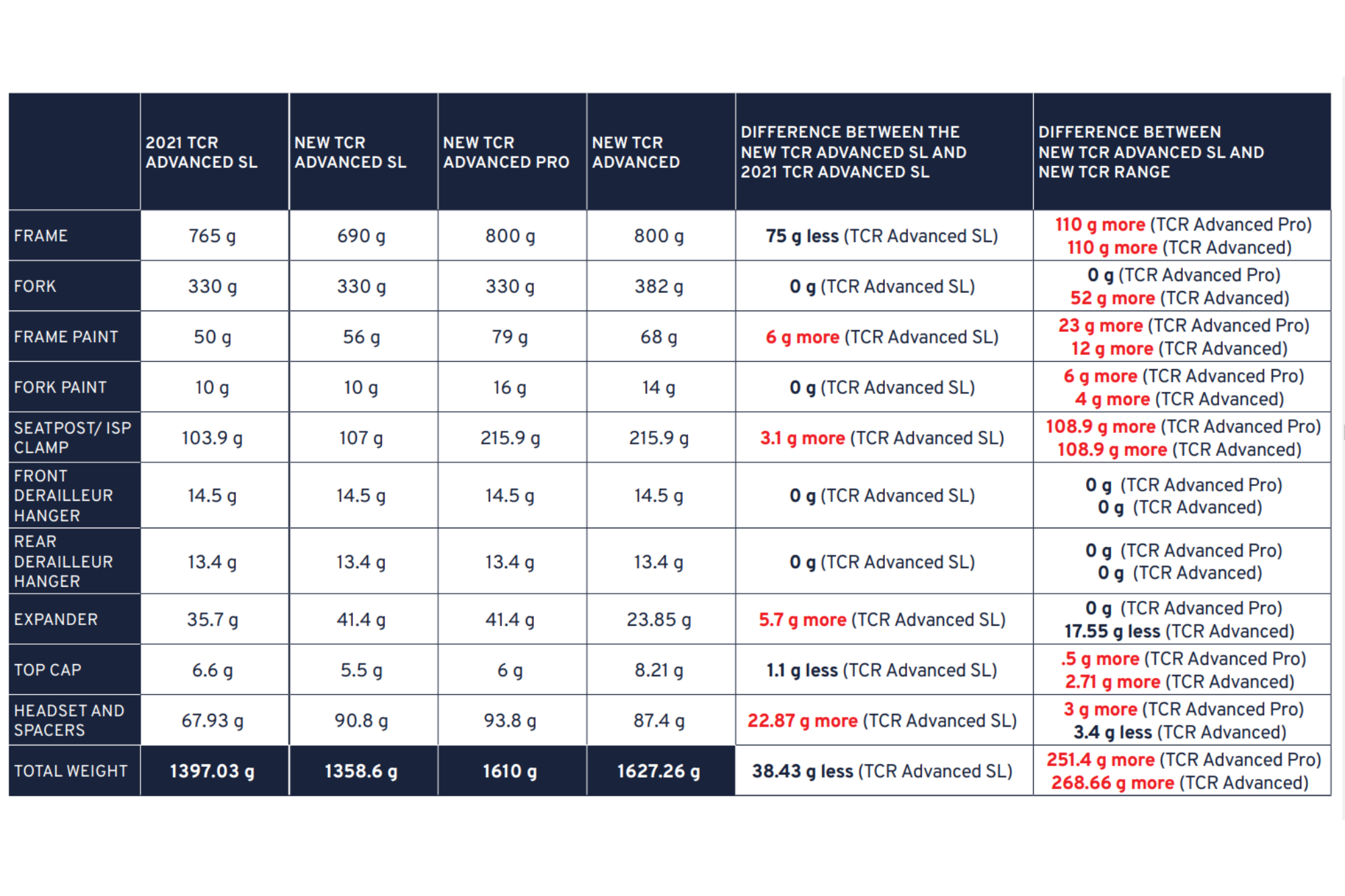

How stiff and how light? Well, the new frame is claimed to weigh 690 grams without paint - 75 grams less than the previous generation TCR and 155 grams less than the Giant Propel. The Specialized S-Works Aethos is claimed to have a frame weight of 585 grams - but there is so much variance in the way that frames are measured, it probably is best to compare weights of fully built models. The Specialized S-Works Aethos with Dura-Ace has been weighed at 6.23kg and the TCR comes in at 6.4kg

When it comes to stiffness, the difference is marginal. The transmission stiffness (a combination of the stiffness at the fork and around the bottom bracket) has gone from 149.8 N/mm to 150.6 N/mm. That’s a 0.53% improvement, which is as small as it sounds. But, as Andrew Jukaitis highlighted: “we could have made the frame stiffer if we wanted to, but there’s a point at which, as a rider, you don’t want the bike to be any stiffer” - otherwise the ride just ends up harsh.

Coming back to the frame, with the 10th generation TCR now being disc brake specific, the opportunity opened up for the most significant changes to the tube shapes between this and the previous model. The seat stay yoke that gave a place to hang a rear brake caliper has been entirely removed, while the seat tube junction and part of the top tube have also been slimmed down.

The TCR’s paint has actually put on a bit of weight - to the tune of 6 grams. Giant has teamed up with 3M (the brand famous for its tapes and protective films) to create a new finish for the TCR’s paintwork. It’s claimed to be particularly tough and scratch resistant, I haven’t tried keying the frameset myself, but I’ll be keeping an eye out for any incidental scuffs - or lack thereof.

Finally, the geometry has remained unchanged compared to the previous TCR and the Giant Propel: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Aero optimization and testing

Much of the aero gains which have been made compared to the previous model are a result of having tucked the cables inside the head tube and also flattening the tops of the handlebars a little - although the adjustments to the tube shapes around the seat post junction have also played a role. All together, these gains sum to a 4.19 watt improvement at 40 kph.

Perhaps more significantly, given how rider position makes up the overwhelming majority of the drag in the rider/bike system, these bars are available in particularly narrow widths. Although the smallest size is nominally 36cm, that’s the width down out the flared out drops - up at the hoods the bars come in at just 34cm.

Now, you might think that Giant has missed a trick with a two piece bar and stem (with its potentially wind-catching face plate) - but Giant has made this spec decision to make bike fit adjustment easier on the stock models. There is a one-piece handlebar available separately - which would save you another two watts on top of that, bringing the savings over the previous generation to a little over six watts. And, let’s face it, even if the bike came with a one piece handlebar, you would probably need to buy a new one that actually fits you anyway, to get the benefits.

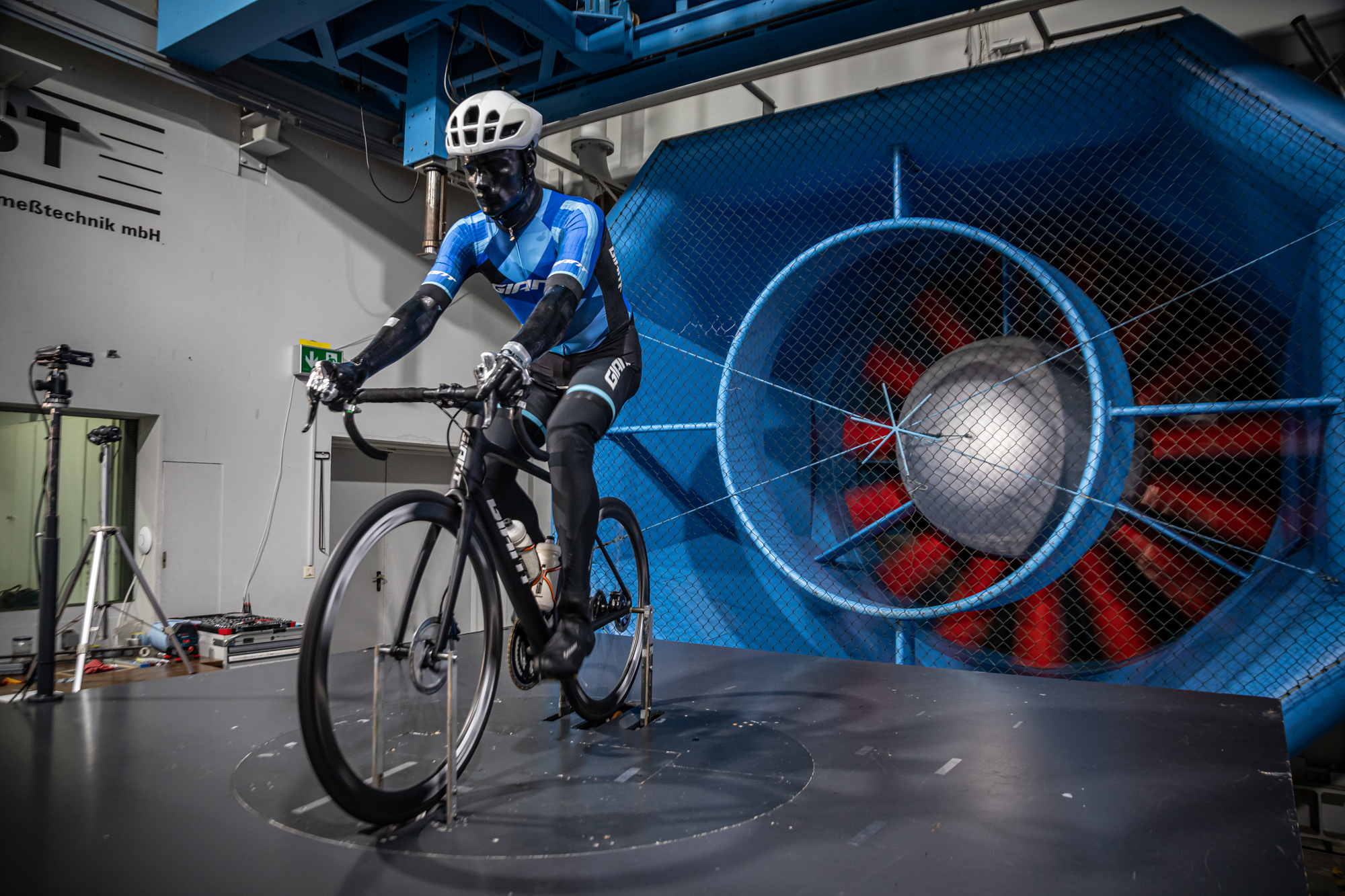

As a bit of an aside, there is a big variance in how different brands test the aerodynamics of their products. Factor is of the belief that having a mannequin on the bike introduces too much noise to the data, making it hard to identify the difference that very subtle tweaks to the shape of their products. SRAM has used outdoor testing with a bar mounted aero sensor - giving true real-world data, but then also having to deal with the associated noise. Other brands, such as Hunt, stress the importance of back-to-back testing on a single day, finding that measurements in the can vary between trips to the wind tunnel - especially when the differences you’re trying to identify are very small.

But Andrew Wollny, Giant's Technical Development Manager, believes that mounting a mannequin with moving legs gives the best balance between the real-world interaction between rider and bike, whilst also being sufficiently fine-grain and repeatable. He also says that their tests from day-to-day are very consistent, which means they’ve built up a massive bank of data.

In fact, even with the mannequin mounted, Wollny says that the resolution of the data is fine enough that he’s able to see the difference that a tweak to an individual tube shape makes. Further than that, he told me he can even see the effect that different tyre pressures have on the aerodynamic efficiency of the complete rider/bike system.

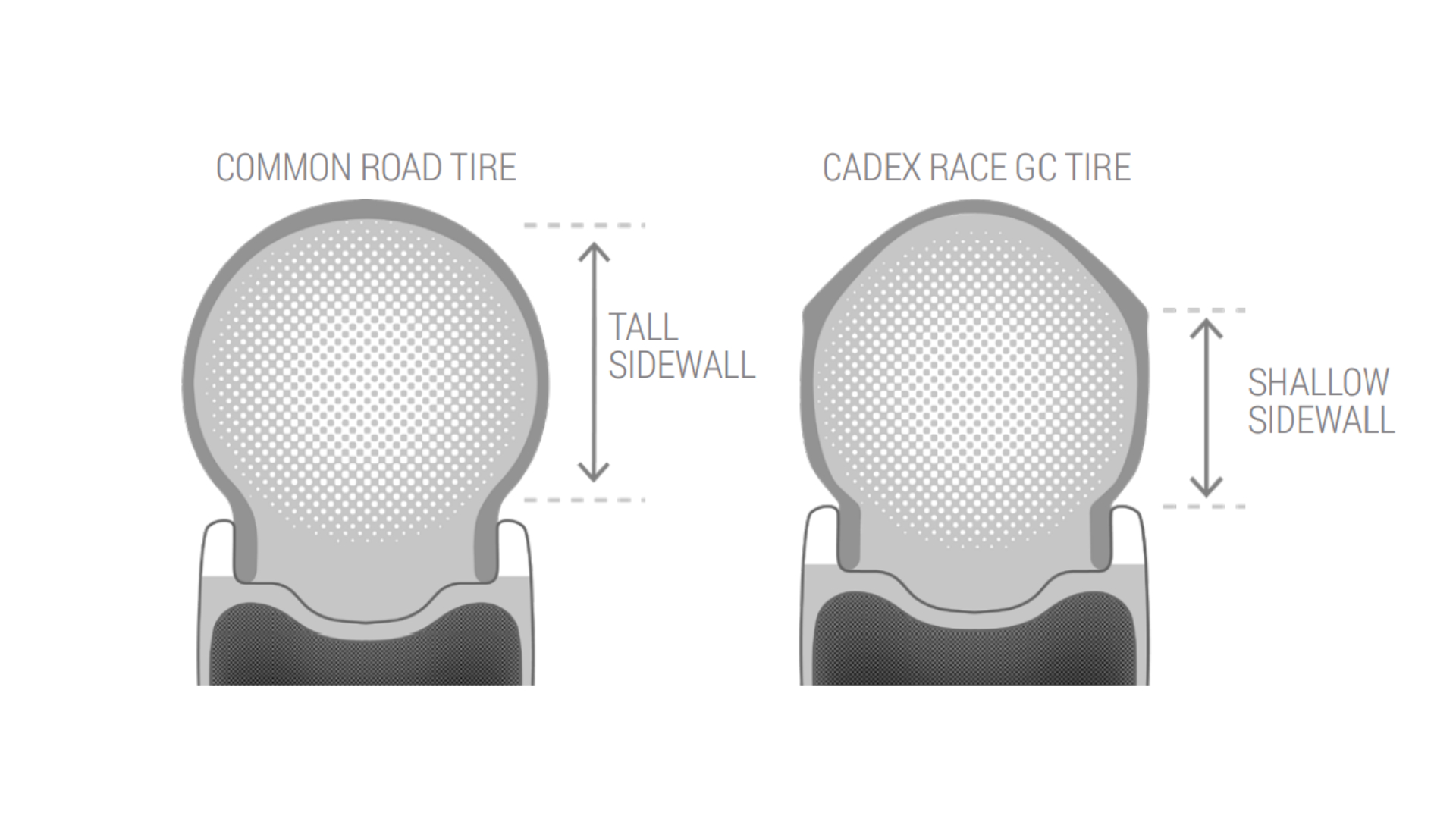

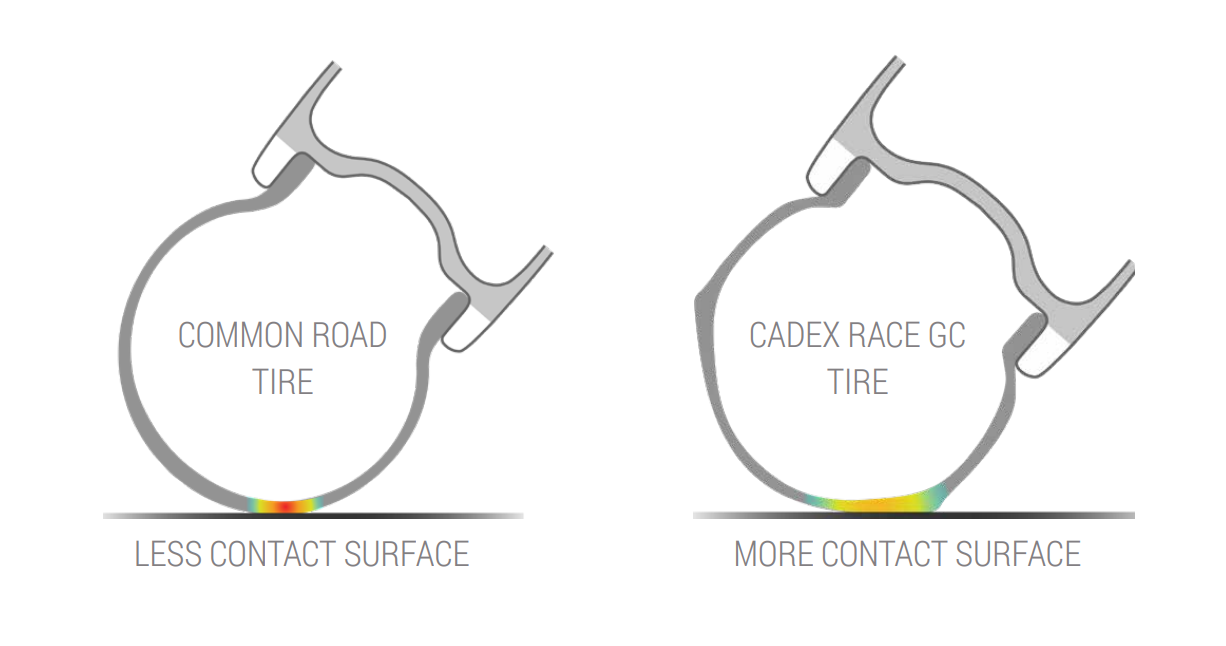

To follow that point and go off on a slight tangent, with most tyres, the higher the pressure the less aero the tyre becomes - as the tyres expands and presents a greater frontal area. There are some expectations, such as Giant’s new Cadex Race GC Tubeless tyres, which have a more parabolic (pointy) profile. As these tyres are inflated to higher pressures, they become proportionally a little taller, making a longer aerofoil, and actually becoming a little more aerodynamic at higher pressures.

But just to stress: aerodynamics aren’t the reason why Giant designed their new tyres like that, and you’re much better off inflating your tyres to the correct pressures for the conditions rather than pumping them hard for ‘aero gainz’ - the point is that even subtle differences such as this are identifiable by Giant’s wind tunnel protocol.

Total system improvement

When it comes to creating a faster bike, improvements to the frameset are just one aspect of a broader picture - the rolling resistance from the tyres and the effect that the wheels have on the aerodynamics are both significant factors, too.

So, to make the TCR faster as a complete package, Giant (or rather, its component brand, Cadex) has developed some new rolling stock for this 10th generation edition - ‘Total System Improvement’, rather than focusing myopically on the frame.

Firstly, let’s look at the wheels, the Cadex Max 40. Beyond just the rim profile, Giant has been focusing on the aerodynamic drag sustained by the spokes as they pass through the air rotationally. The result is 16 carbon spokes on the front and 24 on the rear, each directly bonded to a carbon hub shell flange with hidden nipples inside the rim for adjusting the spoke tension.

As their name suggests, these have a 40mm rim depth and a reasonably wide 22.4mm hookless internal rim width. At a claimed 1,249 grams, they’re lighter than Lightweight’s Obermayer EVO (1,260 grams), but a little heavier than Syncros’ Capital SL carbon Monocoque wheelset (1,172 grams). But on the other hand, Cadex has made its wheels significantly stiffer, so stiff that despite being a little heavier than Syncros’ wheels, the Cadex Max 40 actually have a better stiffness to weight ratio - 10.5% better when measured laterally.

Together with the wheels, there’s now the Cadex Race GC tubeless tyres, which have been made with a supple 240 TPI casing and a Silica-based RR-S Compound for decreased rolling resistance. But perhaps the most novel aspect of these tyres are the ‘micro-profile shoulders’, which are designed to decrease the contact patch when riding in a straight line - yet increase the contact patch when railing through the corners.

Of course, there’s nothing stopping you putting these wheels and tyres in the previous generation TCR and reaping the benefits. But when all these improvements are taken together - the new frame, handlebar, wheels and the tyres - the top-end 10th generation TCR is claimed to be a whopping 12 watts faster than the previously range topping model of the 9th generation TCR.

Models and pricing

The top end model, the TCR Advanced SL 0 - with a Shimano Dura-Ace Di2 groupset, those fancy new Cadex Max 40 wheels and Race GC tyres (although not with the Cadex Aero Integrated Handlebar) comes in at $12,500 / £11,999.

Right at the other end of the price spectrum, we have the TCR Advanced 2. This features Shimano’s 12-speed 105 mechanical groupset, a more basic carbon frame, heavier Giant P-R2 wheels and more robust Giant Gavia Course 1 tyres. The price for this model is $3,200 / £2,699.

You can find the full range over at Giant’s website here.

First ride review

Just a little about the route before moving on to the bike - I’ve never ridden in Taiwan before, so didn’t really know what to expect from the 100km loop and 1,900m of climbing other than that I’d really be getting a chance to get a feel for the TCR on the climbs and through the descents.

Despite starting the route just 20km from the dead centre of Taichung - a city home to 2.8 million people - the roads were so quiet it was as if it were 07:00 in the morning on a Sunday, rather than 09:00 roll out it actually was. The drivers of the few vehicles we did share the road with were wholly considerate - and the roads were simply excellent.

Smooth ribbons of tarmac snaking up the densely forested climbs; the gradients were fairly consistent, generally ranging between about 5 and 13% - enough to really lean into at times, but never leg snappingly steep. So I’ll have to wait until I’m home back in Wales to really test its mettle on our +25% grads and familiar potholes.

Taiwan has some serious mountains: Yu Shan is the highest peak and stands at 3,952m - but you can cycle on tarmac all the way up to 3,275m (the end point of the epic Taiwan KOM Challenge - cycling from sea to summit over 105km). But we stayed around the foothills, with the highpoint topping out at 761m and the low point sitting around 120m. Despite the elevation gain, there were also extended stretches of flat and - seemingly more often than not - brutal headwinds coming in off the coast.

Coming now to the bike, my very first impression from some leg opening sprints back and forth in front of the hotel was the sheer rapidity of the acceleration. Admittedly unsurprising from a 6.4kg build, but it barely took a squeeze on the pedals to spin up to cruising speed.

What was more unexpected was just how well it maintained speed once freewheeling - the deacceleration was markedly slower than what I was expecting. I think this was largely down to the wheels and the optimisations Cadex has put in across the spokes, hub flanges and rim profile. I will be very interested to swap in some different wheels - and pop those Cadex Max 40 hoops on other bike that’s a known quantity - to put that suspicion to the test.

Later on in the ride when putting the power down on the steeper climbs, Giant’s climbs regarding the TCR’s stiffness stacked up. There was no detectable flex around the bottom bracket nor - and this is where I am typically most sensitive - around the head tube. But initially I wasn’t so sure!

You see, it turns out that the handlebars are really quite flexy down in the drops, and in those initial sprints I was quite surprised by the amount of give that they gave. But across the tops they are much, much stiffer - and when pulling on the hoods up steep climbs they were as solid as a rock. Giving some test pulls on the bars when stopped outside a cafe, I could literally see the movement when holding them down in the drops, but I wasn’t able to elicit any noticeable movement from the hoods or tops.

Personally, this suits me quite well. I enjoy short and sharp efforts as part of my training, but it’s been a long time since I’ve been in a serious sprint - I really don’t feel the need for maximum efficiency any more when down in the drops. What I think I will appreciate is the dampening I expect they’ll give when rattling down pitted UK descents - but something to bear in mind if you’ve got the start line in mind.

Another aspect that really stood out to me was that the wheels had a tendency to get caught by the wind when gusts blew through gaps between the trees. The rims were only 40mm, a depth which I generally feel pretty planted on - I think that it might have been the fat carbon spokes acting as a bit of a sail when the wheels were spinning at high speed.

Then again, the test bike I had been given was a size small when I usually ride a medium, so how much it was the wheels vs how much it was the more compact frame, I can’t yet say. Another point to drill into once back in the UK. Also as a result of the smaller frame size, I felt the handling was a little twitchy on the descents - but the geometry is identical to that of the Giant Propel, and having ridden that last year I know it’d be considerably more planted than what I experienced if I was riding a bike that was the right size.

Finally, on those flat sections between the climbs, I had ample time with my nose in the headwinds to ponder about the aerodynamic drag and whether I would have appreciated a deeper section frameset.

I did need all that time, as it took me quite a while to reach my conclusion. As I was riding the TCR, I really enjoyed the zippiness up the climbs and that lightening fast acceleration - with those excellent Cadex 40 Max wheels, I would be very happy with this being my only bike. I wouldn’t feel like I was suffering much of a penalty on the flats - whilst the fun factor is hit dead on.

But then again, the weight difference between the TCR and Propel is only 155 grams. Would I really notice that difference in weight? Barely - if at all. On balance, I think I would actually opt for the Propel: I would rather take the marginal gain in aero performance over the marginal penalty in weight. Were I to get afflicted by a terminal case of weight weenie-ism, that conclusion would change - but I don't see that happening any time, soon.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

After winning the 2019 National Single-Speed Cross-Country Mountain Biking Championships and claiming the plushie unicorn (true story), Stefan swapped the flat-bars for drop-bars and has never looked back.

Since then, he’s earnt his 2ⁿᵈ cat racing licence in his first season racing as a third, completed the South Downs Double in under 20 hours and Everested in under 12.

But his favourite rides are multiday bikepacking trips, with all the huge amount of cycling tech and long days spent exploring new roads and trails - as well as histories and cultures. Most recently, he’s spent two weeks riding from Budapest into the mountains of Slovakia.

Height: 177cm

Weight: 67–69kg