Lost British speed record bike reappears for sale in Berlin - and a crowdfunding campaign aims to reunite it with owner Dave Le Grys

Doing 110mph on a closed motorway in 1986 was only the start of this bike's epic journey

A legendary bike ridden to a British motor-paced cycle speed record of 110mph in 1986 has resurfaced after being lost for three decades - and is for sale for €6,000 on a German website. But a crowdfunding campaign aims to bring it home.

The unique machine was made for Dave Le Grys by South London framebuilder Cliff Shrubb and features a crossover drive system that allows the gear size to be tripled without the use of an enormous single chainring.

Le Grys used it to target the world motor-paced cycle record of 152.28mph, but after his first run at 110mph, which broke the British record, the heavens opened and the attempt was called off.

However, his British record stood for 27 years until Guy Martin broke it in 2013.

At face value €6,000 seems like a fair asking price for a one-off, ultra-rare, record-breaking machine - except Le Grys, now 67, claims the bike is still his and says he wants it back. His problem is that since the bike was given to him in sponsorship, he has no paperwork to prove it.

“It’s complicated,” he admits. “I loaned it to the Harlow bicycle museum in 1987. It was loaned, not given to them.

“That was the first thing that went wrong. Harlow museum closed down and sold all their exhibits to a museum in Cornwall. I tracked it down and said, that’s my bike. But they said they bought it legitimately. I’ve got no paperwork to prove it’s mine. Cliff Shrubb and Ron Kitching, the guys who built the frame and supplied all the equipment, gave it all to me as part of the record attempt.”

Le Grys decided he wouldn’t take it any further and gave up.

“Next I hear it’s gone abroad, Saudi Arabia I think, all over the show and it ended up in Slovakia. Then this guy in Berlin bought it - also legitimately - and I wouldn’t have known if it wasn’t for someone on Facebook saying, is this your bike Dave?

Le Grys tweeted about it, signing off with “FFS”.

However, the legendary bike might finally be on its way home. Lee Widdowson, whose son Harley is the national hill-climb champion at U14 level, spotted Le Grys’s tweet and has set up a crowdfunding campaign on GoFundMe to buy it back.

Widdowson says he stepped in because he regrets selling his son’s U13 winning bike and sympathises with Le Grys, since “to have someone sell [the bike] without his knowledge must be heartbreaking.”

Le Grys plans to put the bike back on display, and says any extra funds raised by the campaign will be donated to a prostate cancer charity.

How the British record was broken

“It was a hell of a journey,” says Le Grys of the 1986 record. “The reason behind doing it, getting sponsorship and how I got it, then doing it, and what happened afterwards. I wanted to do 200mph, that was my life’s ambition. And I’d still do it. If someone said to me there’s your car, there’s the salt flats, away you go. I’d die doing it and I don’t care if I do. If you’re gonna go, you go with a bang.”

The record Le Grys was targeting in 1986 was the world motor-paced cycle record of 152.28mph set a year earlier by John Howard of the USA on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, the world’s primary location for land speed records.

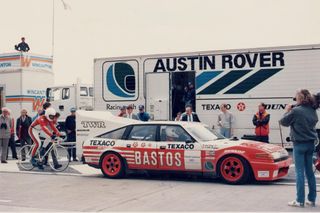

But Le Grys settled for a stretch of unopened M42 motorway in the Midlands lent to him and his team by the Ministry of Transport for the day. He was to be paced by a modified TWR Rover Vitesse SD1 group A touring car with racing driver Win Percy at the wheel. And then the bike…

“I told Cliff [Shrubb] what I wanted,” remembers Le Grys. “I said I need two bottom brackets like a tandem’s crossover drive. But instead of equal chainrings I had different sized chainrings and sprockets so we could triple the gearing. The geometry was taken from the track bike I raced on. It was a 74-parallel 22in frame. He built it around that geometry and stuck two bottom brackets in."

“It was a lovely bit of engineering,” enthuses Le Grys, “and it gave me a 600-odd inch gear. I took it to Saffron Lane velodrome at Leicester and couldn’t ride it. One revolution of the pedals was nearly three-quarters of a lap! Even with a downhill runup you stood on the pedals and they weren’t going round. The gear was ginormous.”

Next the team took it to an airfield to practise the towing from the pace car that would be required before it was possible to turn the pedals.

Shrubb had brazed an upright bar in front of the bike’s head tube that would both serve to tow the bike - it contained the release mechanism - as well as the buffer against the car.

“If you got it [towed] up to 60mph you had a cadence of around 80rpm and then you’re on top of the gear,” Le Grys explains. “You can then release the tow and start cranking it up on your own as the car builds up speed.

“When I pulled the brake it pulled a plunger and that released the tow. The tow was on a bungee and it sprang back into the car. The guy in the back of the car was pulling it in by hand. It was so primitive.”

Le Grys describes how the upright bar also worked as a brake: “I had to hit the back of the car - that was my brake. The bar was upright for a reason. The car had a bump bar behind it, I had to slam into the back of that and the car would brake for me. The bike had a back brake, I tried it once and melted it. There were no disc brakes. So we had to get the speed down to about 60mph before I could use my own brake.”

As Le Grys discovered, it wasn’t just the slowing down that was potentially lethal, but the bike itself, with its steep geometry and short wheelbase, turned out to be far from ideal for the job.

“When you’re doing over 100mph that bike was not stable. How I held the f**king thing up I have no idea. I had a speed wobble at 80-odd mph. I was on a radio hooked up to the driver and I was shouting ‘abort, abort!’ He couldn’t hear me because it was squelching. So he just kept accelerating, which was OK because the speed wobble corrected itself.”

It wasn’t just the bike that wasn’t fully optimised.

“The wind breaker on the back of the car was wrong, my head was sticking out the top and getting buffeted all over the place,” says Le Grys. “I couldn’t see where I was going because we were on a motorway going round bends. When you’re going round a bend you need to look where you’re going. I was suddenly shunted to the right and left and catching a bit of turbulence. If you’ve ever stuck your head out of a car window at 100mph it will give you an idea. It’s a very dangerous area that you can’t go into or you’ll get wiped out.

“As an afterthought I would be landing on concrete, there was a crash barrier that would have taken my head off if I’d slid into it at 100mph. All sorts of things that we didn’t even consider.”

Nevertheless, the 110mph run completed and the British record broken, Le Grys and his team started to adjust the bike’s gearing for a 135mph run.

“We were going to do it in stages,” says Le Grys. “Then it pissed down with rain and we had to abandon it. And the good news really, that bend you see me on in the video, I probably would have crashed at that speed. Everyone was relieved except me. I was spitting dummies out and got the hump because I wanted to do the 135mph run. They said ‘seriously mate, you’re just going to be aquaplaning. Forget it.’”

But the team only had the closed motorway for the day. The following day it was open.

“We had a window and it happened to be a wet, stormy day and that’s all we had,” Le Grys concludes.

His 110mph British record stood for 27 years until it was broken by Guy Martin in 2013 with 112.94mph - a project in which Le Grys himself was involved.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Simon Smythe is a hugely experienced cycling tech writer, who has been writing for Cycling Weekly since 2003. Until recently he was our senior tech writer. In his cycling career Simon has mostly focused on time trialling with a national medal, a few open wins and his club's 30-mile record in his palmares. These days he spends most of his time testing road bikes, or on a tandem doing the school run with his younger son.

-

'Magnus’ death was not an accident - it was a crime' - driver who killed teen cyclist Magnus White found guilty of vehicular homicide

'Magnus’ death was not an accident - it was a crime' - driver who killed teen cyclist Magnus White found guilty of vehicular homicide‘Whatever sentence she receives is not enough,’ says mother of cyclist Magnus White after guilty verdict

By Kristin Jenny Published

-

'Once we were four, I was really confident about winning' - Tenacious Lotte Kopecky hangs in at Tour of Flanders for victory

'Once we were four, I was really confident about winning' - Tenacious Lotte Kopecky hangs in at Tour of Flanders for victoryThe Belgian isn't interested in making history, but is just doing so accidentally

By Adam Becket Published