Smartphone vs bike computer: which is best for adventure riding?

I left my cycling computer at home and rode 360km through Morocco’s High Atlas mountains to find out…

Dropping straight in with a dollop of context, I have always used a cycling computer. When I was 12-years-old and riding laps of the Hillingdon Cycle Circuit, it was just a simple magnet-sensing oedometer attached to my bars. My first one which I could upload a GPX route to was the Garmin 510, although on that model it was just a simple ‘breadcrumb’ trail.

As such, using a cycling-specific GPS unit was something that, for me, almost went without saying. But have I been missing out? Rather than being a navigation system of last resort, could a smartphone actually compete - and even be better than - a traditional bike computer?

For racing applications, I’d say probably not. There, a compact setup isn’t something that can be compromised on. But for bikepacking and non-competitive adventure riding, that’s not so much the case… So, with a 360km bikepacking loop from Marrakech, Morocco and across the High Atlas mountains planned, what better an opportunity to put smartphone navigation to the test - and to challenge my cycling computer presumptions head on!

Just before we set out on our own ride into the mountains, we swung by the startline of the Atlas Mountain Race to round up the best bikepacking tech and rigs we could find - so do check that out. From our own loop of the Atlas mountains, we also came to a verdict on which frame material is best for bikepacking, carbon or steel, which you can find over here. But for now, let’s get into the details on smartphone vs GPS cycling computer.

The kit and cost

Using a Garmin Edge 530 as a reference point, as that’s a great value cycling computer with base maps which I’ve previously bought with my own money, that comes in at $299.99 / £259.99.

I’ll leave the cost of a phone out of it, as pretty much everyone already has one. A charger pack typically comes in around $30 / £25. For adventure cycling, you would be well advised to bring one with you even if navigating with a head unit, but I’ll still tot up the cost of this anyway.

Then there’s the mount. The cheapest options are around $20 / £15, but I went for an SP Connect Handlebar Mount Pro MTB, as that is a particularly neat and slim design - and this model has inbuilt dampening to help protect your phone from the vibrations. This costs $69.95 / £49.95.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

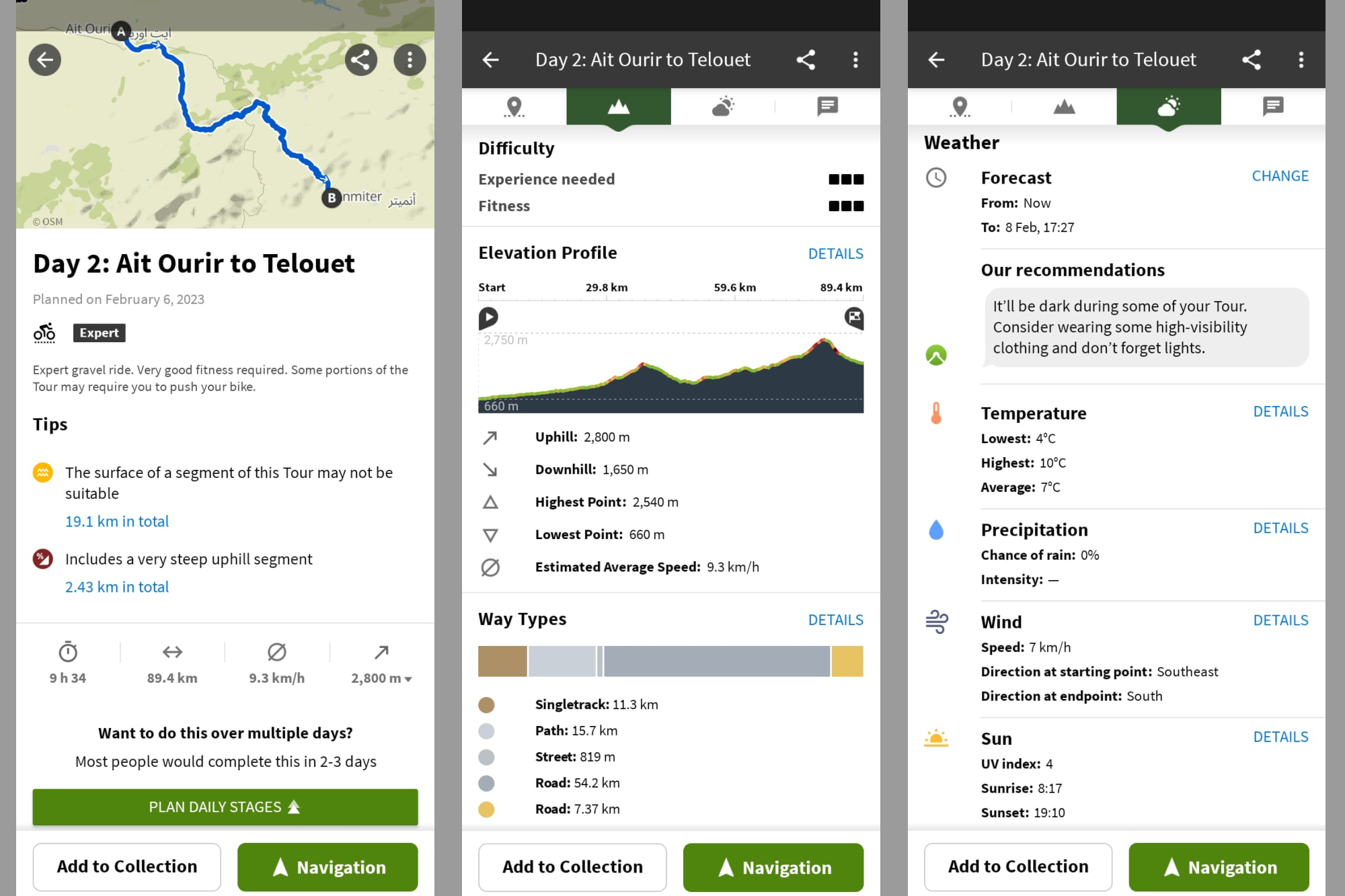

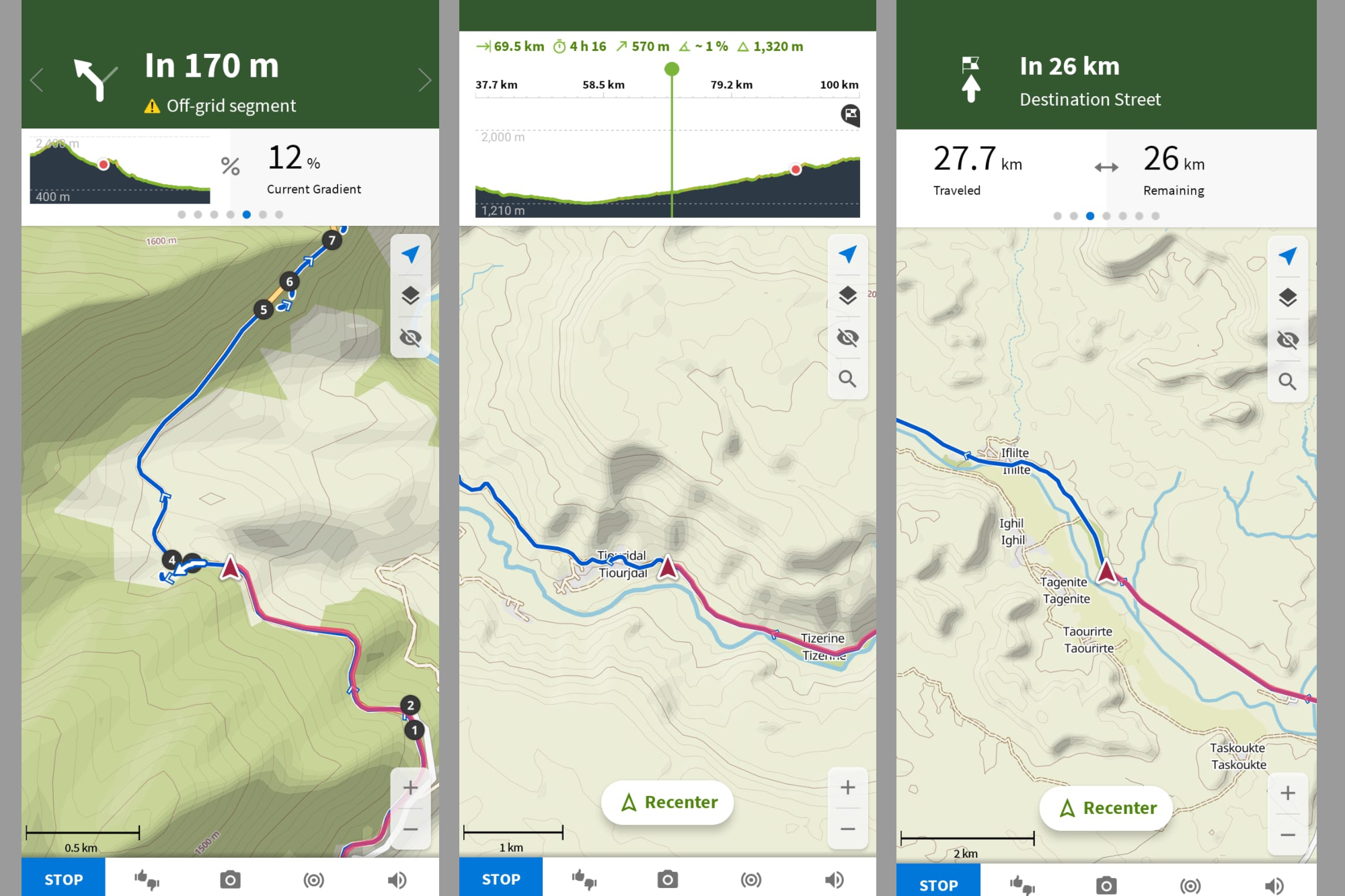

I used the Komoot app for the ride, as it has a good route planning function, offline maps and is easy to use with lots of helpful information about the route and nearby points of interest. It does cost $2.99 a month, though. There are free options, such as maps.me which provide offline mapping, if you want to save that expense.

Finally, there’s the bag to store the battery in. But for adventure cycling of this sort, you will already be needing some form of on-the-bike storage anyway - so factoring that into the cost of the system doesn’t seem fair. The Ortlieb Fuel Pack is one of the best bikepacking bags and costs $75.00 / £57.50 anyway.

So, in terms of which ranks best for price, it’s possible to go much cheaper with a smartphone than even a Garmin Edge 530 - which is widely regarded as one of the best value options for functionality versus price. The setup I was using was rather closer to the price of an Edge 530 but it still came in cheaper, and my kit was very much the de luxe way of going about things - the better comparison would perhaps be with the Garmin Edge 830 (which is has a touchscreen) or the Edge 1040 (which has a less small screen) but those cost $699.00 / £349.99 and $1049 / £519.99.

So round one goes to the smartphone!

Maps, stats and routing

This section is more about Komoot and the functionality of that app specifically against what comes on Garmin's Edge bike computer range or Hammerhead's Karoo 2. Among the best cycling apps for smartphones there are others which present information differently but in the interests of depth over breadth, I’m focusing on Komoot.

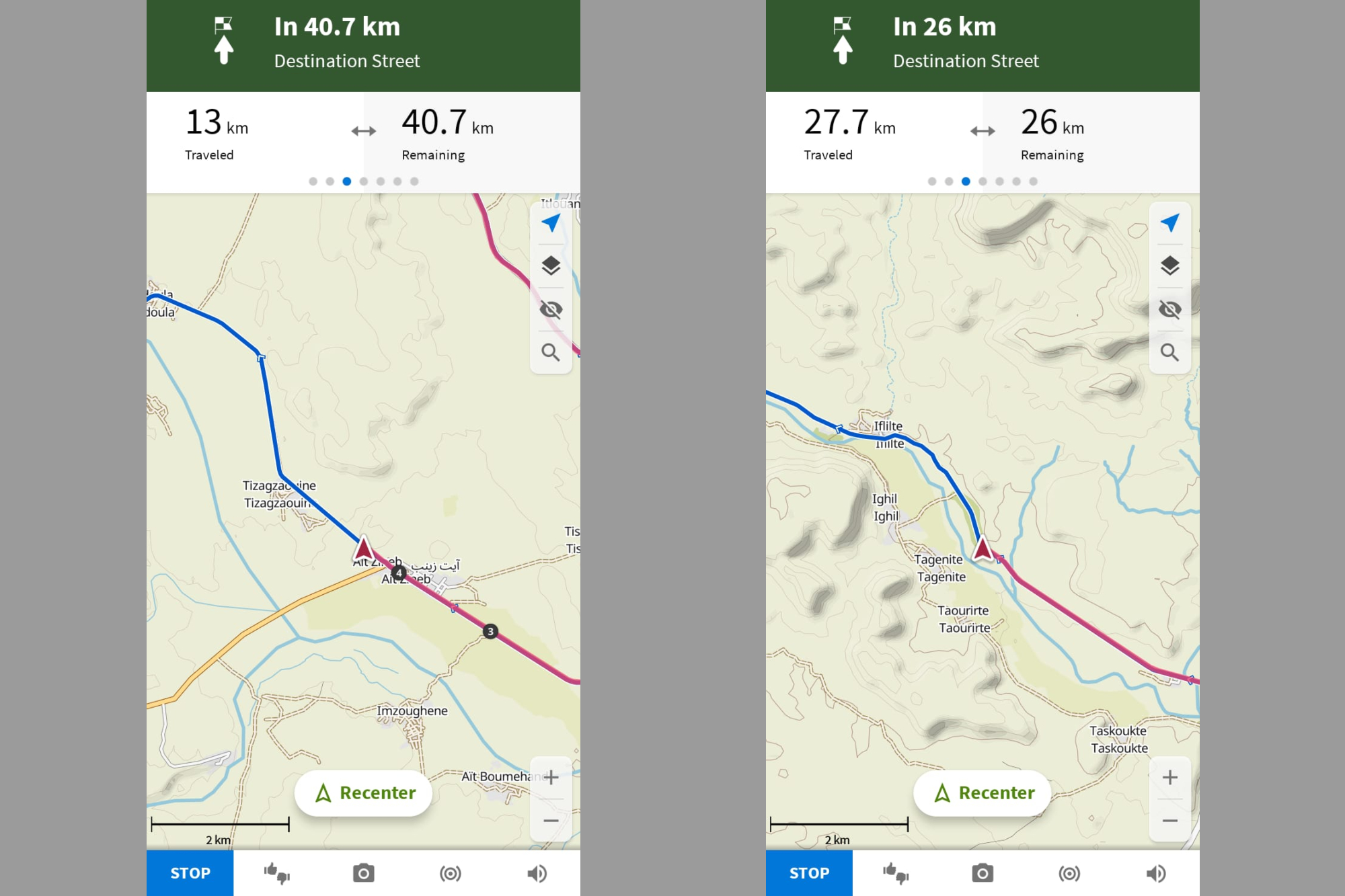

And with the Komoot app, I was impressed by the detail there on the base maps. I was able to see trails of various sizes, names of even the smallest villages, contour lines and general points of interest. You can get that information on a cycling computer, but the size of the screen and the ability to pan and zoom so easily meant that I was able to make much better use of that info - helping me work out more accurately where might be good for a coffee break or toilet stop.

It was also super easy to see the elevation chart for the day, scrubbing backwards and forwards to get the big picture as well as the detail on just how steep the upcoming climb is going to be. Garmin and Hammerhead cycling computers do both have excellent overlays for the current climb you're on, providing detailed information about the gradients and how long you have to go till the top.

But switching to the big picture for the whole day isn’t as quick and easy as it is on Komoot - and that information is incredibly useful when it comes to predicting how much longer the ride is likely to take. 20km is a very different proposition depending on whether it's downhill, flat or actually a 1,000m climb - especially when heavily laden with bags.

Plus, with a smartphone, it’s so quick and easy to switch to Google maps and find a cash point or cafe or restaurant or anything else along your route. Any time you have to be adaptable, it really helps having your smartphone out in front of you.

Of course, it is possible to mount a smartphone as well as a cycling computer on your bars - and there are some situations where you might choose this. Ultra distance racing is the primary example, where riders need to conserve their battery life as much as possible, but still be able to find open shops easily. Also, having a backup navigation system is useful itself. But that situation is quite niche.

When it comes to the mapping, routing and your riding data, I found the Komoot app and the interface of a smartphone actually much easier to use than a traditional GPS unit - round two goes to the smartphone as well!

Size and battery life

For some people, the size of a smartphone screen is one of the key arguments for using one, allowing for more data screens to be squeezed in and more detail on the maps. Others prefer a more compact package which can sit stealthily on the stem and not distract from the ride.

Either of those are personal preference to a large extent, so I won’t dwell on that too much here. What isn’t personal preference is the battery pack you need to keep your phone charged throughout the day - and the top tube or frame pack in which to store the battery pack.

That is a particular limitation of smartphone navigation for rides around the three hour mark which start and finish at home. On these rides I much prefer to travel as light as possible - I wouldn’t want the clutter of a top tube bag and charger cable sticking out.

But in the context of bikepacking, adventure riding and all-day epics, I always bring a charger pack with me - either just-in-case or as a necessity - and I’ll always be carrying some form of bag. So the equipment is all already there, the question is just how much use I make of it or not!

My charger pack is 15,000 mAh, which is quite a lot but still quite a long way short of the biggest you can get. I find it a good balance between its charge capacity and its size and weight - with charging stops at cafes for lunch and restaurants for dinner, I can run my phone off it pretty much indefinitely, even when camping every night away from a power source.

Naturally every use case is different - if you’re traveling somewhere much more remote or if you’re planning on completing the ride as quickly as possible with minimal stops at cafes, then you would be better off using a cycling computer. These are much less power hungry than smartphones, so you’ll get more off a single charge. But each of those cases have to be quite extreme for a charger pack of that size not to be sufficient.

So again, there is some nuance to this one. The size of a traditional cycling computer is better for mid-length rides which start and end at the same place. But in the context of bikepacking and adventure riding, this is another win I’m giving to the smartphone - I would have carried all that kit and those bags on the loop around the Atlas Mountains, whether I was using my phone for navigating or a GPS unit.

Rainproofness

My phone, like most phones, isn’t waterproof - and so navigation in the rain is a bit of a limitation. With Morocco being quite a dry country, this didn’t prove too much of an issue - the only time there was any precipitation was some snowfall at the top of the mountain pass. With there being just one road down, I was able to just pop my phone into the top tube bag and take it out at the next junction.

The next junction was often very far away

That worked as a solution in that situation, but it’s not as good as having a GPS unit which can handle a downpour. There are waterproof cases you can buy, but generally these make the phone bulkier and harder to operate, so they’re not without downsides. Other than that, you could instead invest in a waterproof phone (which is useful in many situations).

So, although there are options and workarounds for riding through inclement weather, it is more of a faff and not as straightforward as with a bike computer. This round goes to the cycling computers - at least until more smartphones are made to be waterproof.

Conclusion

It might challenge the cycling orthodoxy - no doubt someone will label it heretical - but for bikepacking, leisure, and adventure oriented rides without a competitive element, I think that smartphone navigation does now actually edge out a traditional cycling computer.

You can access much more detail about your route and there’s nothing quicker and easier for on-the-fly navigation. The battery life in most cases is a moot point, as for these rides you’ll most likely be taking a charger pack with you - and I find 15,000mAh lets me run pretty much indefinitely (with top up charges at cafes and restaurants).

Yes, when you’re riding straight out your front door on a 3-hour loop, it’s nicer having something more compact and which doesn’t need a charger pack. But for all-day and multi-day epics, the only real downside is that most phones aren’t waterproof - and waterproof cases are generally quite clunky and do make the phone harder to use. That said, there are many phone models which are waterproof now, so this might be less of a concern.

If you're looking to find a mount to get started with using your smartphone for rides, check out our guide to the best waterproof cycling phone cases and mounts.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

I’ve been hooked on bikes ever since the age of 12 and my first lap of the Hillingdon Cycle Circuit in the bright yellow kit of the Hillingdon Slipstreamers. For a time, my cycling life centred around racing road and track.

But that’s since broadened to include multiday two-wheeled, one-sleeping-bag adventures over whatever terrain I happen to meet - with a two-week bikepacking trip from Budapest into the mountains of Slovakia being just the latest.

I still enjoy lining up on a start line, though, racing the British Gravel Championships and finding myself on the podium at the enduro-style gravel event, Gritfest in 2022.

Height: 177cm

Weight: 60–63kg

-

ROUVY's augmented reality Route Creator platform is now available to everyone

ROUVY's augmented reality Route Creator platform is now available to everyoneRoute Creator allows you to map out your home roads using a camera, and then ride them from your living room

By Joe Baker

-

Day or night, I never ride without my Garmin Varia rearview radar light; it's one of the best pieces of cycling tech I've ever owned

Day or night, I never ride without my Garmin Varia rearview radar light; it's one of the best pieces of cycling tech I've ever ownedDeals The Varia RCT715 is, for me, an essential piece of riding kit delivering enhanced safety, and right now, it has a superb $100 off at REI

By Paul Brett