What’s going on with Specialized's welds?

With the welds of the Allez Sprint starkly splitting opinion, we ask the experts for their view on Specialized's welds

Following the launch of the new Specialized Allez Sprint, there’s one particular aspect of the frame that has set comment sections and forums ablaze – the welding.

Or, to be more specific, those striking welds around the head tube.

Now, svelte joins have never really been a particular feature of the Allez Sprint. The bottom bracket welds of the previous model had quite an industrial look to them – arguably starker and more prominent than the head tube welds of this latest iteration.

But perhaps it's the prominence in the field of view that makes the welding around the new Allez Sprint’s head tube stand out so noticeably to some. Here’s a flavour of the comments…

“That welding looks awful, looks like the frames snapped and then been welded back together!” said David Fairburn, on YouTube.

“Looks like the apprentice has had a go… on day one.” said Colin McBadass on Twitter.

“What's with the bad welds on this frameset? I hope that it is intentional.” said Samuel on YouTube.

Of course, the comments weren’t all one-sided, and the frames had plenty of support too.

“They’re in a slightly different place than what people are used to and therefore ‘bad.’” reflected Bike Snob NYC on Twitter.

“You had me at ‘alloy.’ Take my money and ship it fast.” said John Daly on Facebook.

We covered the reasons for the locations of the welds and the design behind them in the launch story. But briefly, the idea is that by moving the welds back from the head tube and further along the top and down tubes, the join is further away from where the highest stresses are.

Specalized’s reaction

CW contacted Specialized for its perspective on the reception of the welds and for further clarification on the performance benefits: how much weight the new design saves over the previous model and the difference in stiffness – measured in Newtons per millimetre of deflection – between the two models.

The brand's statement was as follows.

“Innovation driven by engineering pushes the boundaries of material and frequently challenges traditional perspectives of aesthetics or design. The Allez Sprint is truly a case of form follows function.

“To deliver this level of performance in alloy – specifically with the massive aero gains, power transfer, and handling – our engineering team leveraged our Smartweld technology to create something entirely new for riders.

“Our differences are what make us better, and we’re excited about the overwhelmingly positive responses we’ve received from riders about the Allez Sprint’s performance.

“Of course this is nothing new in cycling. Over the years, leading innovators in the industry embrace advancements that others often question based on aesthetic opinions. From aero bars to disc brakes, if the performance gains are undeniable, the aesthetics become the norm over time.”

A framebuilder's perspective

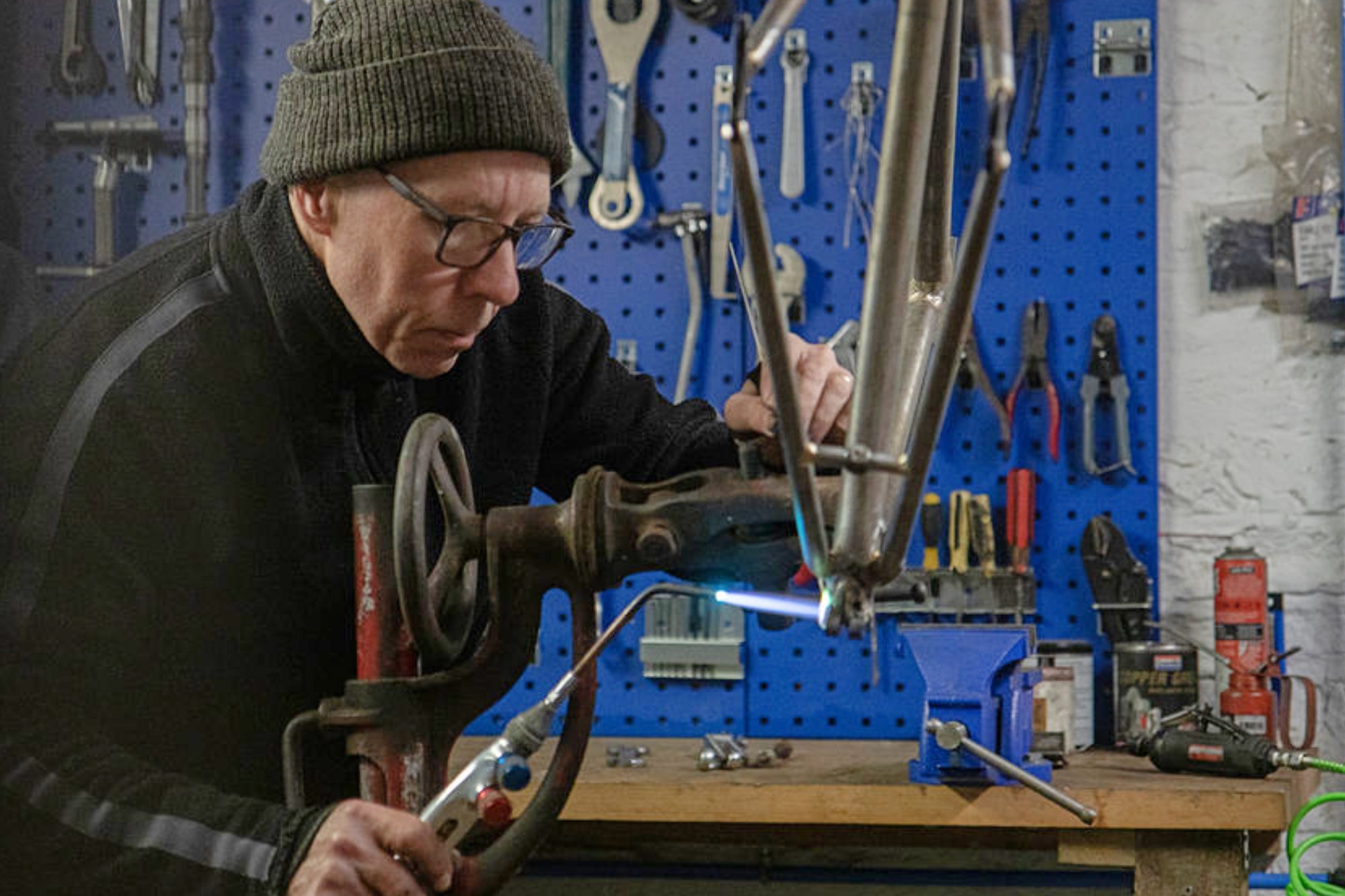

Most framebuilders work with steel. It’s a ductile, durable metal that’s relatively easy to work with – a bespoke frame is already a costly affair and with the amount of time and effort invested, it is something you’ll very much want to last.

Although Vernon Barker Cycles – established in 1979 and based in Sheffield – still sticks to steel for its handbuilt frames, it is among the very small number of independent British companies that do repairs of both aluminium and titanium frames, and so is quite familiar working with other metals

Vernon Barker himself still takes an active interest in the shop, but the business was passed on to Dave Baillie in 2011 and it was with him I spoke about the Allez Sprint.

The first point Baillie stressed to me was that “it’s impossible to know how good a weld is without taking the frame apart” and without cutting a frame open there’s going to be a certain element of speculation. Despite that, there still is much that can be said about the choice of location for the welds.

“Normally when you join a down tube to a head tube, what you’re effectively doing is trying to get the weld area to be the smallest possible circumference that it could possibly be. What [Specialized] has done is make the join at quite a pronounced angle so that the weld is almost in a vertical line perpendicular to the ground.”

Just because something is the established way of doing things isn’t in itself a good argument against a different method. Wheels with deeper section rims were quite a departure from the box-sections of old, but the performance benefits were palpable.

Regarding the Allez Sprint’s welds, Baillie went on to elaborate: “You really want to reduce the amount of weld area as much as possible because, basically, the smaller the join the stronger it’s going to be. If you look at what Specialized has done, they’ve actually increased the size of the weld.”

“It’s probably not a significant difference, but mechanically I just don’t really see the justification.”

Similarly, for the positioning of the welds further back from the head tube, Baillie explained: “I understand what they’re saying about the stress and the forces, but the join has only been moved by about 15 or 20 millimetres, so there is still going to be plenty of stress there.

“Potentially more, even, as those extra bits of tube sticking out from the head tube could end up acting almost as a lever, extenuating any flexing from the head tube. Again, it’s not really likely to be anything significant, shouldn’t cause any problems at all, it just strikes as a bit pointless.”

A second framebuilder’s perspective

The Taverna family have been handbuilding frames as 'contractors' in Padova, Italy since 1947. Among their current customers is London-based Racer Rosa. Today, titanium, carbon and aluminium are all employed, along with the traditional steel, of course. The grandson of Giovanni Taverna – the man who founded the family business – Antonio Taverna is the current master frame builder and it was him who I asked about the new Allez Sprint.

When it came to the placement of the welds on the top tube and down tube, Antonio Taverna does believe that this would indeed likely increase the strength of the frame. “It makes sense from a 'robustness' point of view – the use of these forged 'lugs' moves the stress away from the critical points. But my question is: how often did the previous Allez frame break at those critical points?”

He went on to say: “I think this is likely to be one of those solutions to a problem that did not exist. With regards to the weight, any saving is likely to be marginal – in fact, if anything, this method will add a bit of weight instead, in my opinion.”

A post shared by Racer Rosa Bicycles (@racerrosabicycles)

A photo posted by on

But regarding the aesthetics, although so much Italian engineering pays such strong attention to the form as well as the function, Taverna himself was disarmingly pragmatic: “Nothing is large or ugly in my opinion. For mass-produced frames, it is a matter of strength and also cost. You simply don't want to smooth out TIG welding because this reduces the welds' strength and the extra time adds to the production costs.

“Of course, for hand-built frames, that’s a totally different matter. The TIG welding used for this typically uses double the material of mass-produced frames and the hand-made smoothing makes the welds even stronger, as well as being more gentle to the eye. But then it does add a lot of labour and therefore cost.”

On the performance benefits of the new design, Antonio was more skeptical: “I realise you'd tend to think that this 'stronger' forged lug method allows you to use lighter weight tubing – but I think this cannot be the case.

“The tubing would still need to be double-butted at least and so there should be essentially no difference in weight between the old Allez Sprint and the new one. If there is, it is almost certainly not because of the different construction method.

“I think that the motivations behind such a product is merely a financial operation. It is not trying to do something different or innovative, that performs better, is stronger or has a longer life. Rather, I think it is trying to do something much less expensive to mass-produce and therefore maximise the profit margins even more than before.

“The number and the difficulty of welds and the welding time would likely be drastically reduced, hence the production costs too. You could potentially weld such a frame in about 10 minutes. Ultimately, it is a simple and economical way to make a frame.”

Hot or not?

When it comes to the aesthetics, on the whole, I’m on board with the Allez Sprint.

The bottom bracket area looks so much better than the previous model and, with the BB now sitting in a continuation of the down tube, I’d argue the look tops out more traditional designs with a greater number of welds.

For some reason, the welds of the top tube just don’t jar with me. To draw a quick analogy, I think an exposed drivetrain on a town bike looks a lot better than anything with a chain-guard attached – perhaps I’m just more drawn to engineering that’s worn on its sleeve.

It’s really the cable routing of the 105 spec model that I feel leaves something to be desired. I’m not against cables being on show, I’m part of the minority that would love nothing better than for brake and gear cables to be routed externally for the entirety of their length.

But if the cables are to be routed internally, then it would be nice for them to look a little neater. Orbea manages to do this on bikes starting at £1,349 / $1,999. Sure, the higher spec LTD models of the Allez Sprint do have a much neater cockpit, but these aren’t available in all countries (the UK does miss out), and in the USA, the pricing stands at $6,800.

Regarding the performance, that’s something we’ll only be able to pass judgement on once we’ve reviewed it.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

After winning the 2019 National Single-Speed Cross-Country Mountain Biking Championships and claiming the plushie unicorn (true story), Stefan swapped the flat-bars for drop-bars and has never looked back.

Since then, he’s earnt his 2ⁿᵈ cat racing licence in his first season racing as a third, completed the South Downs Double in under 20 hours and Everested in under 12.

But his favourite rides are multiday bikepacking trips, with all the huge amount of cycling tech and long days spent exploring new roads and trails - as well as histories and cultures. Most recently, he’s spent two weeks riding from Budapest into the mountains of Slovakia.

Height: 177cm

Weight: 67–69kg

-

'One of the hardest races I've ever done in my life' - Tadej Pogačar finishes runner-up on Paris-Roubaix debut after crash

'One of the hardest races I've ever done in my life' - Tadej Pogačar finishes runner-up on Paris-Roubaix debut after crashWorld champion reacts to 'extremely hard' battle with Mathieu van der Poel

By Tom Davidson Published

-

'I thought it would be dark by the time I got here' - Joey Pidcock, the last rider to finish Paris-Roubaix, on his brutal day out

'I thought it would be dark by the time I got here' - Joey Pidcock, the last rider to finish Paris-Roubaix, on his brutal day outQ36.5 rider finishes outside time limit, but still completes race with lap of the Roubaix Velodrome

By Adam Becket Published